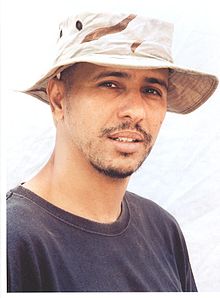

Mohamedou Ould Slahi has been held without charge in Guantánamo for 11 years. He was kidnapped by the U.S. government in November 2001, flown to Jordan where he was held for eight months. The Jordanians concluded he had not engaged in terrorism but the U.S. nevertheless transferred him to Bagram Air Base in Afghanistan and then two weeks later to Guantánamo.

Mohamedou Ould Slahi has been held without charge in Guantánamo for 11 years. He was kidnapped by the U.S. government in November 2001, flown to Jordan where he was held for eight months. The Jordanians concluded he had not engaged in terrorism but the U.S. nevertheless transferred him to Bagram Air Base in Afghanistan and then two weeks later to Guantánamo.

What followed was one of the most stubborn, deliberate, and cruel Guantánamo interrogations on record. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld personally signed Slahi’s interrogation plan. Like Mohamed al-Qahtani, the Pentagon’s other “Special Project,” Slahi would be subjected to months of 20-hour-a-day interrogations that combined sleep deprivation, severe temperature and diet manipulation, and total isolation with relentless physical and psychological humiliations. He was told his mother had been detained and would soon be at the mercy of the all-male population at Guantánamo. He was threatened with death and subjected to a violent mock rendition. Declassified files, including the Defense Department’s Schmidt-Furlow Report, the Justice Department’s investigation of FBI involvement in Guantánamo interrogations, and the Senate Armed Services Committee’s report on the treatment of detainees, document the Pentagon’s plan and its meticulous and malicious implementation.

That all this abuse was fruitless is clear from the 2010 decision of U.S. District Court Judge James Robertson granting Slahi’s habeas corpus petition and ordering his release. Once there had been talk of trying Slahi as a key 9/11 recruiter, a capital crime, but no criminal charges were ever prepared against him. The man first assigned to prosecute him, Marine Corps Lt. Col. Stuart Couch, withdrew from the case when he discovered Slahi had been tortured. When Couch’s boss, former Guantánamo chief prosecutor Col. Morris Davis, met with the CIA, the FBI, and military intelligence in 2007 to review Slahi’s case, the agencies conceded they could not link him to any acts of terrorism. During Slahi’s habeas corpus proceedings, the government still alleged he played a role in recruiting the 9/11 hijackers, though by then it was acknowledging, as Robertson notes in a footnote to his opinion, “that Slahi probably did not even know about the 9/11 attacks.” The only evidence the government offered to support allegations of Slahi’s involvement in terrorist plots came, Robertson found, from statements he made in the course of his brutal interrogation.

Slahi testified by closed video link to Washington during the habeas corpus proceedings. What he said remains classified. Until now, one of the few documents we had of Slahi describing his ordeal, in his own words, is the declassified transcript of his November 2005 Administrative Review Board hearing. The document is remarkable for the characteristic clarity and sly humor of Slahi’s voice; a masked interrogator, he tells the board, “had gloves, OJ Simpson gloves on his hands.” It is also exceptionally earnest. Early in his statement, he tells the board, “Please, I want you guys to understand my story okay, because it really doesn’t matter if they release me or not, I just want my story understood.”

At the time, Slahi was already working on his memoir. When his pro bono attorneys met him for the first time in April 2005, he greeted them with 100 handwritten pages. With their encouragement, he delivered additional installments over the next year, complaining at one point in a letter, “You ask me to write you everything I told my interrogators. Are you out of your mind! How can I render uninterrupted interrogation that has been lasting the last 7 years? That’s like asking Charlie Sheen how many women he dated.” And yet Slahi’s writing is much more than a litany of abuses. It is driven by something much deeper: not just the desire to “be fair,” as he puts it, but to understand his guards, his interrogators, and his fellow detainees as protagonists in their own right, and to show that even the most dehumanizing situations are composed of individual, and at times harrowingly intimate, human exchanges. The result is an account that is both damning and redeeming.

From Slahi’s memoir, May, 2003 — some names and other words have been redacted:

In the block the recipe started. I was deprived of my comfort items, except for a thin iso-mat and a very thin, small, and worn-out blanket. I was deprived of my books, which I owned. I was deprived of my Quran. I was deprived of my soap. I was deprived of my toothpaste. I was deprived of the roll of toilet paper I had. The cell — better, the box — was cooled down so that I was shaking most of the time. I was forbidden from seeing the light of the day. Every once in a while they gave me a rec time in the night to keep me from seeing or interacting with any detainees. I was living literally in terror. I don’t remember having slept one night quietly; for the next 70 days to come I wouldn’t know the sweetness of sleeping. Interrogation for 24 hours, three and sometimes four shifts a day. I rarely got a day off.

“We know that you are a criminal.”

“What have I done?”

“You tell me, and we reduce your sentence to 30 years. Otherwise you will never see the light again. If you don’t cooperate we are going to put you in a hole and wipe your name out of our detainees database.” I was so terrified because I knew, even though he couldn’t make such decision on his own, he had the complete backup of the high government level. He didn’t speak from the air.

“I don’t care where you take me, just do it.”

When I failed to give him the answer he wanted to hear, he made me stand up, with my back bent because my hands were shackled with my feet and waist and locked to the floor. [ ? ? ? ? ?] turned the temp control all the way down, and made sure that the guards maintained me in that situation until he decided otherwise. He used to start a fuss before going to his lunch, so he kept me hurt during his lunch, which took at least two to three hours. [ ? ? ? ? ?] likes his food; he never missed his lunch. I was wondering, how could [ ? ? ? ? ?] have possibly passed the fitness test of the Army? But I realized he is in the Army for a reason.

The fact that I wasn’t allowed to see the light made me “enjoy” the short trip between my freakin’ cold cell and the interrogation room. It’s just a blessing when the warm GTMO sun hit me. I felt the life sneaking back into every inch of my body. I always had this fake happiness, though for a very short time. It’s like taking narcotics.

“How you been?” said one of the Puerto Rican escorting guards, with his weak English.

“I’m OK, thanks, and you?”

“No worry, you gonna back to your family,” he said. When he said so I couldn’t help breaking into [ ? ? ? ? ?]. Lately, I had become so vulnerable. What’s wrong with me? Just a soothing word in this ocean of agony was enough to make me cry. [Continue reading…]