Mary Fitzgerald writes: It didn’t take long before one of the incentives offered to coax the Taliban to the negotiating table came to light: last week the Guardian carried reports of American plans to release several high-ranking Taliban leaders from Guantánamo Bay. They include Mullah Khair Khowa, a former interior minister, Noorullah Noori, a former governor in northern Afghanistan and maybe, just maybe, the former army commander Mullah Fazl Akhund – if a third country, perhaps Qatar, will accept custody of him.

It’s an inevitable step in the right direction, reminiscent of the tentative early moves in the Northern Ireland peace process. It also offers a convenient, if partial, solution to the status of the 171 legal headaches still languishing in America’s brutal Caribbean prison.

But it forces into light other shaming questions about the conduct of the so-called war on terror; and in particular about those thousands of men, women and children, many innocent of any crime even by the US authorities’ own admission, who were “rendered” and remain trapped in prisons across the world.

Hamidullah Khan was just 13 when he disappeared from South Waziristan, in Pakistan. I met his father, Wakeel Khan, on a recent trip to Islamabad. He told me with pride that Hamidullah was a “very good-looking boy” and showed me pictures. He said his son could be quite absent-minded, but worked very hard at school: his dream was to become a doctor.

During the summer holidays in 2008, Wakeel sent Hamidullah to the family home in South Waziristan to collect some of their possessions, as Wakeel could not get the time off work to go himself. Hamidullah never returned.

Wakeel, an ex-solider, tried to retrace his son’s steps. He caught the bus up to the province, and asked everyone about his son: his relatives, his old army contacts, the local Taliban. No one knew anything. He thought of going to the police, but given that they charge a 300 rupee bribe to replace an ID card, he asked himself, “how much would they charge to find a person?”

After a year, the Red Cross finally tracked down Hamidullah and passed a letter to his family saying he was being held in Bagram prison in Afghanistan. Despite American assurances that the prisoners there are treated well, fresh allegations of abuse surfaced this weekend.

No explanation has ever been offered for why a boy so young was picked up and taken hundreds of miles away, why he has never been charged, and why he has still not been released.

Category Archives: war in Afghanistan

Afghan commission: U.S. abuses detainees

The Associated Press reports: An Afghan investigative commission accused the American military Saturday of abusing detainees at its main prison in the country, saying anyone held without evidence should be freed and backing President Hamid Karzai’s demand that the U.S. turn over all prisoners to Afghan custody.

The demands put the U.S. and the Afghan governments on a collision course as negotiations continue for a Strategic Partnership Document with America that will determine the U.S. role in Afghanistan after 2014, when most foreign troops are due to withdraw. By pushing the detainees issue now, Karzai may be seeking to bolster his hand in the negotiations.

At the center of the dispute are hundreds of suspected Taliban and al-Qaida operators captured by American forces. The controversy mirrors that surrounding the U.S. detention center at Guantanamo Bay. There, as at the prison in Afghanistan, American forces are holding many detainees without charging them with a specific crime or presenting evidence in a civilian court.

Dial 1 to speak to the Taliban

The Economist‘s Asia blog considers the prospects for peace in Afghanistan now that the Taliban has an official address — a political office in Qatar.

Peace with the Taliban has three main actors and a large unsupporting cast. The opening of a Taliban office in Qatar suggests a change of direction from one of the essential players, Pakistan. Previous attempts by senior Talibs to talk to the Americans and the Afghan government have been nixed by Pakistan, anxious to maintain a stranglehold over the Taliban movement and ensure that any peace process worked in Islamabad’s interests. Just last year when the media reported that Tayeb Agha, the former secretary to the Taliban supreme leader Mullah Omar, had been holding secret talks with German and American diplomats, his entire family in Pakistan was promptly put under house arrest.

The latest round of talks that led to the Qatar breakthrough was once again led by Mr Agha. Western experts in Kabul think the plan would never have got this far without a degree of Pakistani involvement, which in turn implies a measure of support from Islamabad.

America, the second big player, hopes that by dangling the possibility of releasing senior Taliban prisoners held in Guantanamo in exchange for a ceasefire, it can nurture a serious peace process. At the same time, American diplomats are talking tough, trying to convince the Taliban that they cannot win in the long-run, and have no chance of sweeping back to power and re-establishing their old regime.

For those Taliban who pay attention to geopolitics, the argument is convincing. First, a little background. The circumstances that saw the Taliban rise to power in 1996 are unlikely to be repeated. In those days America had withdrawn from Afghan affairs, whilst the Soviet Union no longer existed. Without the involvement of the two great superpowers, the field was left clear for Pakistan.

Afghanistan’s neighbour had long been anxious to see a weak, pliant regime in Kabul that would be hostile to India and not assert claims to territory ceded in 1893, under British pressure, to what is now Pakistan. Pakistan eventually got everything it wanted by throwing support behind an obscure bunch of pious former mujahideen led by Mr Omar, back when he was just a one-eyed mullah living in the rural outskirts of Kandahar. Pakistan’s infamous Inter-Services Intelligence agency (ISI) helped put these religious “students”, or Taliban, in power by giving them military support, as well as paying-off power brokers who stood in their way.

Fast forward to today and things look far less congenial for the Taliban. Despite American weariness at the high cost in lives and treasure, it remains unlikely that Afghanistan will be abandoned again. Today’s insurgency remains a phenomenon restricted to just one ethnic group, the Pashtuns. Consequently it lacks the nationwide appeal that the mujahideen enjoyed in the 1980s. In military terms the insurgents have been clobbered in swathes of the south. They are only really vigorous in a relatively small number of districts. Also, despite the notorious short comings of the Karzai administration, the Afghan state continues to strengthen. In such circumstances it would make sense for the insurgents to make a deal sooner rather than later.

Taliban leaders held at Guantánamo Bay to be released in peace talks deal

The Guardian reports: The US has agreed in principle to release high-ranking Taliban officials from Guantánamo Bay in return for the Afghan insurgents’ agreement to open a political office for peace negotiations in Qatar, the Guardian has learned.

According to sources familiar with the talks in the US and in Afghanistan, the handful of Taliban figures will include Mullah Khair Khowa, a former interior minister, and Noorullah Noori, a former governor in northern Afghanistan.

More controversially, the Taliban are demanding the release of the former army commander Mullah Fazl Akhund. Washington is reported to be considering formally handing him over to the custody of another country, possibly Qatar.

The releases would be to reciprocate for Tuesday’s announcement from the Taliban that they are prepared to open a political office in Qatar to conduct peace negotiations “with the international community” – the most significant political breakthrough in ten years of the Afghan conflict.

The Taliban are holding just one American soldier, Bowe Bergdahl, a 25-year-old sergeant captured in June 2009, but it is not clear whether he would be freed as part of the deal.

“To take this step, the [Obama] administration have to have sufficient confidence that the Taliban are going to reciprocate,” said Vali Nasr, who was an Obama administration adviser on the Afghan peace process until last year. “It is going to be really risky. Guantánamo is a very sensitive issue politically.”

U.S. no longer able to disregard Pakistan’s sovereignty

The New York Times reports: With the United States facing the reality that its broad security partnership with Pakistan is over, American officials are seeking to salvage a more limited counterterrorism alliance that they acknowledge will complicate their ability to launch attacks against extremists and move supplies into Afghanistan.

The United States will be forced to restrict drone strikes, limit the number of its spies and soldiers on the ground and spend more to transport supplies through Pakistan to allied troops in Afghanistan, American and Pakistani officials said. United States aid to Pakistan will also be reduced sharply, they said.

“We’ve closed the chapter on the post-9/11 period,” said a senior United States official, who requested anonymity to avoid antagonizing Pakistani officials. “Pakistan has told us very clearly that they are re-evaluating the entire relationship.”

American officials say that the relationship will endure in some form, but that the contours will not be clear until Pakistan completes its wide-ranging review in the coming weeks.

The Obama administration got a taste of the new terms immediately after an American airstrike killed 26 Pakistani soldiers near the Afghan border last month. Pakistan closed the supply routes into Afghanistan, boycotted a conference in Germany on the future of Afghanistan and forced the United States to shut its drone operations at a base in southwestern Pakistan.

Mushahid Hussain Sayed, the secretary general of the Pakistan Muslim League-Q, an opposition political party, summed up the anger that he said many harbored: “We feel like the U.S. treats Pakistan like a rainy-day girlfriend.”

Whatever emerges will be a shadow of the sweeping strategic relationship that Richard C. Holbrooke, President Obama’s special envoy for Afghanistan and Pakistan, championed before his death a year ago. Officials from both countries filled more than a dozen committees to work on issues like health, the rule of law and economic development.

All of that has been abandoned and will most likely be replaced by a much narrower set of agreements on core priorities — countering terrorists, stabilizing Afghanistan and ensuring the safety of Pakistan’s arsenal of more than 100 nuclear weapons — that Pakistan will want spelled out in writing and agreed to in advance.

With American diplomats essentially waiting quietly and Central Intelligence Agency drone strikes on hold since Nov. 16 — the longest pause since 2008 — Pakistan’s government is drawing up what Prime Minister Yousaf Raza Gilani called “red lines” for a new relationship that protects his country’s sovereignty and territorial integrity.

Said an American official: “Both countries recognize the benefits of partnering against common threats, but those must be balanced against national interests as well. The balancing is a continuous process.”

First, officials said, will likely be a series of step-by-step agreements on military cooperation, intelligence sharing and counterterrorism operations, including revamped “kill boxes,” the term for flight zones over Pakistan’s largely ungoverned borderlands where C.I.A. drones will be allowed to hunt a shrinking number of Al Qaeda leaders and other militants.

The C.I.A. has conducted 64 missile attacks in Pakistan using drones this year, compared with 117 last year and 53 in 2009, according to The Long War Journal, a Web site that tracks the strikes.

In one of the most visible signs of rising anti-American sentiment in this country, tens of thousands of protesters took to the streets of Lahore and Peshawar this month. And on Sunday in Karachi, Pakistan’s biggest city, at least 100,000 people rallied to support Imran Khan, a cricket celebrity and rising opposition politician who is outspoken in his criticism of the drone strikes and ties with the United States.

The supposed threat posed by Imran Khan is nothing more than the danger that Pakistan might get a government that was more loyal to the will of the Pakistani people than its paymasters in Washington. Khan’s promise, if his party was to gain power, is to purge the country of corruption. Those who regard him as a threat must presumably see corruption as their friend.

From Pakistan to Afghanistan, U.S. finds convoy of chaos

Bloomberg Businessweek reports: Like a broker tracking the dips and spikes of a volatile but lucrative stock, Mohammad Shakir Afridi has kept a close eye on U.S. troop levels in Afghanistan since the first Americans landed in the country 10 years ago. As president of the Khyber Transport Assn., one of the largest associations of truck owners in Pakistan, Afridi’s biggest contract involves moving military equipment for American and coalition forces through Pakistan to military bases in Afghanistan. The slightest policy shift in Washington can carry major consequences for Afridi and his business.

Sitting on a rooftop in a leafy residential block in Peshawar, the largest city in northwest Pakistan, Afridi slaps the morning paper on the floor beside his mat. “Twenty-four of our boys in one go,” he spits out. A front page photograph shows a field full of coffins draped in Pakistani flags. The soldiers were killed on Nov. 26 when U.S. helicopters and jet fighters from Afghanistan fired on military outposts on the Pakistani side of the border. The relationship between Pakistan and the U.S., which has been rocky for years, hit a new low. While the U.S. military promised to investigate and the NATO chief regretted the “tragic, unintended” incident, the Pakistani Prime Minister said there would be “no more business as usual” with the U.S. Pakistan demanded the U.S. vacate an airbase it was using in the South and choked off all U.S. and coalition military supplies traveling through the country.

Afridi learned of the American attack before the Pakistan military or government had issued any statement; one of his truck drivers called to tell him the border was closed. Afridi was later given orders from the military to halt trucks near the border, and to direct all others to the southern port city of Karachi. He quickly obliged. “It’s serious this time,” Afridi says. “They’ll make the Americans sweat.”

U.S. and Allied forces in Afghanistan get the bulk of their supplies in two ways. The first is the Northern Distribution Network, a web through Central and Eastern Europe and Central Asia that crosses through at least 16 countries, using a combination of roads, railway, air, and water to move supplies in from the north. The chain can be complex and circuitous. One path through the network, for example, might involve military cargo that arrives by sea in Istanbul. From there it travels the width of Turkey on truck and crosses the northern border into Poti, Georgia. In Georgia the equipment goes by rail to Baku in Azerbaijan, where it’s loaded onto a ship bound for the Kazakh Port of Aktau, across the Caspian Sea. Then it’s put on trucks for the 1,000-mile ride through Kazakhstan, then a train through Kyrgyzstan and, finally, into Afghanistan.

The second passage to Afghanistan, known as Pakistani Lines of Communication, begins at the port of Karachi and continues on one of two land routes, north toward the logistical hub at Bagram Airfield or west toward Kandahar. It has always been the primary option for American forces: It’s the shortest and cheapest, requires only one border crossing, and minimal time on the road inside Afghanistan. Nearly 60,000 trucks drive more than 1,200 miles through the length of Pakistan every year carrying supplies and fuel. According to varying figures provided by U.S. and NATO forces, 40 percent to 60 percent of all military supplies used by coalition forces in Afghanistan come through Pakistan. [Continue reading…]

Obama administration considers censoring Twitter

How dangerous can 140 characters be?

Apparently if those 140 characters are being fired onto the web through the Twitter account of al Shabib, Somalia’s militant jihadist movement, then the national security of the United States could be in jeopardy.

The New York Times reports:

American officials say they may have the legal authority to demand that Twitter close the Shabab’s account, @HSMPress, which had more than 4,600 followers as of Monday night.

The most immediate effect of the Obama administration’s threat appears to have been that @HSMPress (which has so far only made 114 tweets) has subsequently gained hundreds of new followers.

Is Twitter itself about to take a stand in defense of freedom of speech?

A company spokesman, Matt Graves, said [to a Times reporter] on Monday, “I appreciate your offer for Twitter to provide perspective for the story, but we are declining comment on this one.”

Last Wednesday, the New York Times reported from Nairobi in Kenya:

Somalia’s powerful Islamist insurgents, the Shabab, best known for chopping off hands and starving their own people, just opened a Twitter account, and in the past week they have been writing up a storm, bragging about recent attacks and taunting their enemies.

“Your inexperienced boys flee from confrontation & flinch in the face of death,” the Shabab wrote in a post to the Kenyan Army.

It is an odd, almost downright hypocritical move from brutal militants in one of world’s most broken-down countries, where millions of people do not have enough food to eat, let alone a laptop. The Shabab have vehemently rejected Western practices — banning Western music, movies, haircuts and bras, and even blocking Western aid for famine victims, all in the name of their brand of puritanical Islam — only to embrace Twitter, one of the icons of a modern, networked society.

On top of that, the Shabab clearly have their hands full right now, facing thousands of African Union peacekeepers, the Kenyan military, the Ethiopian military and the occasional American drone strike all at the same time.

But terrorism experts say that Twitter terrorism is part of an emerging trend and that several other Qaeda franchises — a few years ago the Shabab pledged allegiance to Al Qaeda — are increasingly using social media like Facebook, MySpace, YouTube and Twitter. The Qaeda branch in Yemen has proved especially adept at disseminating teachings and commentary through several different social media networks.

“Social media has helped terrorist groups recruit individuals, fund-raise and distribute propaganda more efficiently than they have in the past,” said Seth G. Jones, a political scientist at the RAND Corporation.

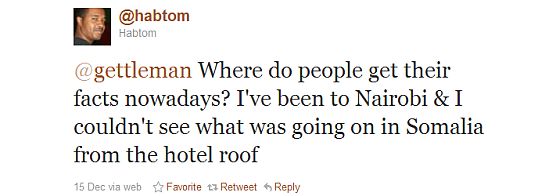

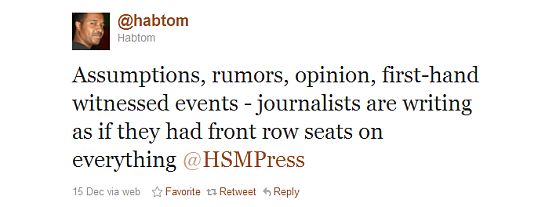

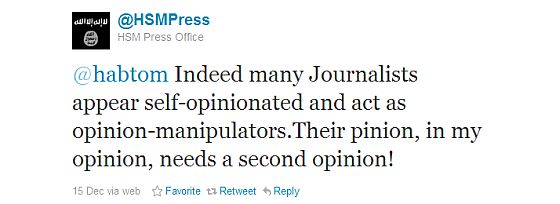

The Times reporter, Jeffrey Gettleman, sounds quite indignant that al Shabib should have the audacity to be using Twitter, so he can hardly have been surprised that his article prompted this exchange between @HSMPress and one of their followers:

Somalia is not the only front in the new war on Twitter.

The Washington Post reports on Twitter battles in Afghanistan:

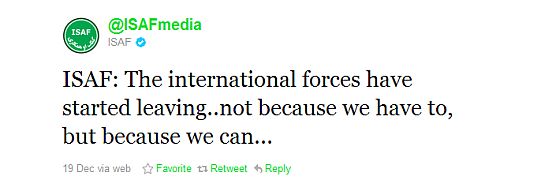

U.S. military officials assigned to the International Security Assistance Force, or ISAF, as the coalition is known, took the first shot in what has become a near-daily battle waged with broadsides that must be kept to 140 characters.

“How much longer will terrorists put innocent Afghans in harm’s way,” @isafmedia demanded of the Taliban spokesman on the second day of the embassy attack, in which militants lobbed rockets and sprayed gunfire from a building under construction.

“I dnt knw. U hve bn pttng thm n ‘harm’s way’ fr da pst 10 yrs. Razd whole vilgs n mrkts. n stil hv da nrve to tlk bout ‘harm’s way,’ ” responded Abdulqahar Balkhi, one of the Taliban’s Twitter warriors, who uses the handle @ABalkhi….

U.S. military officials say the dramatic assault on the diplomatic compound convinced them that they needed to seize the propaganda initiative — and that in Twitter, they had a tool at hand that could shape the narrative much more quickly than news releases or responses to individual queries.

“That was the day ISAF turned the page from being passive,” said Navy Lt. Cmdr. Brian Badura, a military spokesman, explaining how @isafmedia evolved after the attack. “It used to be a tool to regurgitate the company line. We’ve turned it into what it can be.”

So how’s @isafmedia exploiting the power of Twitter? With tweets like this?

A we’re-winning-the-war tweet like this might sound good inside ISAF’s Twitter Command Center, but I don’t think it’s going to impress anyone else.

The problem the Obama administration is up against is not the threat posed by its adversaries on Twitter; it is that its own ventures into social media are predictably inept. Official tweets lack wit and tend to sound like the clumsy propaganda. But when losing an argument, the solution is not to look for ways to gag your opponent — that’s how dictators operate.

The Pentagon prides itself on its smart bombs. Can’t it come up with a few smart tweets?

Bleak future for returning U.S. veterans

The Economist reports: Brett Quinzon did two tours in Iraq before leaving active duty in May. Originally from Minnesota, Mr Quinzon now lives in Thomaston, a small town around 65 miles south of Atlanta. A grey December morning found him filling out forms in Atlanta’s large veterans’ hospital, seeking treatment for depression. Since returning from Iraq, he says he has “more anger issues”, and finds himself “more watchful and on-guard in public situations” than he was before he deployed. That is not unusual: many soldiers return from the battlefield with psychological scars. Between January and May, as he prepared to leave active duty, Mr Quinzon applied for hundreds of jobs. The search proved difficult: like many veterans, he enlisted right after high-school, and lacks a college degree. But persistence paid off. He is now an apprentice at a heating and air-conditioning company, and is being trained as a heavy-equipment operator.

Not all recent veterans are so lucky. Around 800,000 veterans are jobless, 1.4m live below the poverty line, and one in every three homeless adult men in America is a veteran. Though the overall unemployment rate among America’s 21m veterans in November (7.4%) was lower than the national rate (8.6%), for veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan it was 11.1%. And for veterans between the ages of 18 and 24, it was a staggering 37.9%, up from 30.4% just a month earlier.

If demography is indeed destiny, perhaps this figure should not be surprising. More soldiers are male than female, and the male jobless rate exceeds women’s. Since so many soldiers lack a college degree, the fact that the recession has been particularly hard on the less educated hits veterans disproportionately. Large numbers of young veterans work—or worked—in stricken industries such as manufacturing and construction. Whatever the cause, this bleak trend is occurring as the last American troops leave Iraq at the end of this year, and as more than 1m new veterans are expected to join the civilian labour force over the next four years.

Secret U.S., Taliban talks reach turning point

Reuters reports: After 10 months of secret dialogue with Afghanistan’s Taliban insurgents, senior U.S. officials say the talks have reached a critical juncture and they will soon know whether a breakthrough is possible, leading to peace talks whose ultimate goal is to end the Afghan war.

As part of the accelerating, high-stakes diplomacy, Reuters has learned, the United States is considering the transfer of an unspecified number of Taliban prisoners from the Guantanamo Bay military prison into Afghan government custody.

It has asked representatives of the Taliban to match that confidence-building measure with some of their own. Those could include a denunciation of international terrorism and a public willingness to enter formal political talks with the government headed by Afghan President Hamid Karzai.

The officials acknowledged that the Afghanistan diplomacy, which has reached a delicate stage in recent weeks, remains a long shot. Among the complications: U.S. troops are drawing down and will be mostly gone by the end of 2014, potentially reducing the incentive for the Taliban to negotiate.

Still, the senior officials, all of whom insisted on anonymity to share new details of the mostly secret effort, suggested it has been a much larger piece of President Barack Obama’s Afghanistan policy than is publicly known.

U.S. officials have held about half a dozen meetings with their insurgent contacts, mostly in Germany and Doha with representatives of Mullah Omar, leader of the Taliban’s Quetta Shura, the officials said.

The stakes in the diplomatic effort could not be higher. Failure would likely condemn Afghanistan to continued conflict, perhaps even civil war, after NATO troops finish turning security over to Karzai’s weak government by the end of 2014.

Success would mean a political end to the war and the possibility that parts of the Taliban – some hardliners seem likely to reject the talks – could be reconciled.

The effort is now at a pivot point.

“We imagine that we’re on the edge of passing into the next phase. Which is actually deciding that we’ve got a viable channel and being in a position to deliver” on mutual confidence-building measures, said a senior U.S. official.

While some U.S.-Taliban contacts have been previously reported, the extent of the underlying diplomacy and the possible prisoner transfer have not been made public until now.

Inside Story – 2014: A U.S. free Afghanistan?

CIA drones quit one Pakistan site — but U.S. keeps access to other airbases

The Bureau of Investigative Journalism reports: Despite its very public withdrawal from Shamsi airfield at the weekend, the United States continues to have access to a number of military airfields inside Pakistan – including at least one from which armed drones are able to operate, the Bureau understands.

The first concrete indications have also emerged that the US has now effectively suspended its drone strikes in Pakistan. The Bureau’s own data registers no CIA strikes since November 17.

Islamabad is furious in the wake of a NATO attack which recently killed 24 Pakistani soldiers on its Afghan borders. As well as suspending NATO supply convoys through Pakistan, anti-aircraft missiles have also reportedly been moved to the border with Afghanistan. Pakistan also demanded that the US withdraw from Shamsi, a major airfield in Balochistan controlled and run by the Americans since late 2001.

US Predator and Reaper drones have operated from the isolated airbase for many years. Technically the base is leased to Abu Dhabi in the United Arab Emirates, which allowed Pakistan to deny a US presence for many years. Now the US has quit Shamsi, with large US transporter planes stripping military hardware from the base.

But the US will continue to have access to at least five other Pakistani military facilities, according to a Pakistani source with extensive knowledge of US-Pakistani military and intelligence co-operation.

Does the U.S. military want Afghanistan to get even nastier?

The Guardian reports: Even by Afghanistan‘s high standards, the massacre of Shia worshippers in Kabul on Tuesday 6 December was an act of stomach-churning brutality. A suicide bomber posing as a pilgrim on Ashura, one of the holiest days of the calendar of Shia Islam, had inveigled his way into the middle of a packed crowd of men, women and children. Witnesses watching from the rooftop of the nearby Abu Fazal shrine said body parts flew up into the air near the epicentre of the blast when the unknown bomber detonated himself.

The clearing smoke revealed a scene strewn with lifeless and often mangled bodies, lying in circles around the blackened area of tarmac where the bomber had stood. A young girl who had somehow miraculously survived was snapped by a photographer wailing into the air. Among the 55 killed there were no police officers or soldiers or anyone who might remotely be considered a “legitimate” target of the Taliban-led war against the Afghan government.

The Taliban itself was quick to condemn the attack in strong terms, while an extremist Pakistan-based movement called Lashkar- e-Jhangvi al Almiv has been fingered. If it really was a unilateral operation launched without the consent of the Taliban’s leadership it is another worrying sign of how the insurgency in Afghanistan is spinning out of control, becoming crueller and ever more willing to inflict horrendous damage on ordinary civilians.

But not everyone thinks such horrors are an entirely bad thing. Indeed, some within the US war machine have long argued the emergence of a nastier insurgency could be really quite useful for Nato‘s war aims. So useful, in fact, that foreign forces should try to encourage such behaviour.

One of them was Peter Lavoy, a former chairman of the US National Intelligence Council, the body that examines data from across the US government’s intelligence gathering machine and turns it into high-grade analysis that is rarely discussed publicly. At a closed-door meeting with ambassadors at Nato headquarters in Brussels in December 2008, Lavoy spelled out a strategy for winning the war in Afghanistan that has never been uttered publicly: “The international community should put intense pressure on the Taliban in 2009 in order to bring out their more violent and ideologically radical tendencies,” he said, according to a State Department note-taker in the room. “This will alienate the population and give us an opportunity to separate the Taliban from the population.”

His words, which we only know courtesy of WikiLeaks, are extraordinary because they have been proven at least partially right. They also differ fundamentally from the publicly stated strategy in Afghanistan. Known as population-centric counterinsurgency, or Coin, the fundamental principle is that foreign forces should try to keep ordinary Afghans safe from insurgents and thereby win their support.

The idea that Nato may actually be trying to make the population less secure appalls observers. “It just goes completely against the ethos of the American military not to take more risks in order to protect civilians,” says John Nagl, a retired lieutenant-colonel who co-wrote the US army’s field manual on countering guerrilla warfare. “I find it hard to believe elements of the US military would want to deliberately put more risk on to civilians.”

But behind the scenes, powerful voices continue to argue for a harder-edged strategy that makes the lives of ordinary Afghans more miserable, not less. Michael Semple, a regional expert on the Taliban, says it is an outlook he runs across in discussions with Nato officials: “I have heard serious, thinking officers articulate the idea that provoking Taliban fighters into acts of extreme violence against the population could be taken as a sign of Coin progress, prior to the final victory when the people turn against them.”

U.S.-Pakistan relations deteriorate

Al Jazeera reports: The US has vacated the Shamsi air base in Pakistan’s Balochistan province after a 15-day ultimatum given by Islamabad, prompted by the deaths of at least 24 of its soldiers in a NATO air raid last month.

Sunday’s withdrawal was completed when the final flight carrying US personnel and equiptment flew out.

Nine planes carrying personnel and 20 carrying equiptment – including drone aircraft and weapons – left for neighbouring Afghanistan, officials said.

Shamsi was believed to be the staging post for US drones operating in northwest Pakistan and neighbouring Afghanistan.

Meanwhile, a senior Pakistani military official told a US television network on Sunday that his country “will shoot down any US drone that enters its territory”.

Al Jazeera’s Kamal Hyder, reporting from Islamabad, said that Pakistani parliamentarians had “asked their air chief whether they had the capability to shoot down the drones if they were to violate their frontiers”.

“The air chief told them point blank that the decision to shoot down the drones was a political one and if they were ordered to do so they would comply,” he said.

Rare attacks on Shiites kill scores in Afghanistan

The New York Times reports: A Pakistan-based extremist group claimed responsibility for a series of coordinated bombings aimed at Afghan Shiites on Tuesday, in what many feared was an attempt to further destabilize Afghanistan by adding a new dimension of strife to a country that, though battered by a decade of war, has been free of sectarian conflict.

The attacks, among the war’s deadliest, struck three Afghan cities — Kabul, Kandahar and Mazar-i-Sharif — almost simultaneously and killed at least 63 Shiite worshipers on Ashura, which marks the death of Shiite Islam’s holiest martyr.

One of the dead in Kabul was an American man, according to the Public Health Ministry. The American Embassy confirmed that there had been an American fatality but declined to identify the victim.

Targeted strikes by Sunnis against the minority Shiites are alien to Afghanistan. So it was no surprise to Afghans when responsibility was claimed by a Sunni extremist group from Pakistan, where Sunnis and Shiites have been energetically killing one another for decades.

The group, Lashkar-e-Jhangvi, had not previously claimed or carried out attacks in Afghanistan, however, and its emergence fueled suspicions that Al Qaeda, the Taliban or Pakistan’s spy agency — or some combination of those three — had teamed up with the group to send the message that Afghanistan’s future stability remained deeply tenuous and indeed dependent on the cooperation of outside forces.

“Never in our history have there been such cruel attacks on religious observances,” said President Hamid Karzai, in a statement released by his office. “The enemies of Afghanistan do not want us to live under one roof with peace and harmony.”

The timing of the attacks was especially pointed, coming a day after an international conference on Afghanistan in Bonn, Germany, that had been viewed as an opportunity for Afghanistan to cement long-term support from the West.

Why Afghans have come to hate Americans

U.S. and Afghan government officials are struggling to reach a strategic long-term agreement — the sticking point is Afghan opposition to night raids which have surged under the Obama administration and now happen as often as 40 times a night.

NATO officials say they have modified how night raids are conducted in response to the Afghan government’s concerns.

“Ninety-five percent of all night operations at this stage are already partnered,” said Brig. Gen. Carsten Jacobson, the NATO spokesman in Afghanistan. “So basically the recommendation of the traditional loya jirga is already put into action.”

“It is in our combined interest that as soon as possible, Afghanization is accomplished,” he added, referring to an Afghan takeover of security responsibility.

Mr. Faizi was unimpressed by that argument. “According to reports from our officials in different provinces, the Afghan security forces are leaving with the American forces to go conduct night operations without being informed directly where they are going, which house they are searching and who is the target,” he said.

While General Jacobson said night raids averaged 10 a night now, a recent study of night raids by the Open Society Foundations, financed by George Soros, estimated that 19 a night were taking place during the first three months of 2011.

The American military is so enamored of the tactic that some generals have said that without night raids, the United States may as well go home.

General Jacobson said that 85 percent of night raids took place without a single shot fired, and that over all such operations accounted for less than one percent of all civilian casualties.

Statistics might calm the doubts of feeble-minded U.S. senators, but they will have little to no impact on the perceptions of Afghans whose homes are being violated. To live in a country where there is an ever-present risk of foreign soldiers breaking into your house in the middle of the night is to live in a state of oppression. This is the nature of occupation.

[Aimal Faizi, the spokesman for President Hamid Karzai,] said the raids were the biggest complaints that Mr. Karzai heard when visitors from the provinces met with him.

“If one of the messages of the United States is to win the hearts and minds of the Afghan people, then these night raids are totally against this,” he said. “People are becoming more and more against the international presence in Afghanistan.”

On the frontlines of southern Helmand Province, the governor of Sangin district, Mohammad Sharif, is a critic of the practice, even though his district has been the center of some of the toughest fighting of the war, with among the highest casualty rates for NATO forces. He said the Special Operations forces that carried out the raids often got the wrong people, including many pro-government people. “People are not happy, and they feel bad toward Americans,” he said.

A high-ranking official in Helmand Province saw the matter differently, although he did not want to be quoted by name endorsing night raids because of their unpopularity. “So many Taliban commanders have been killed or detained in night raids, and if it wasn’t for them, we would not have the peace we now have,” he said. “Taliban commanders are like snakes: it’s hard to catch them, and night raids are their charmers.”

He also noted that trying to arrest a Taliban commander during the day would inevitably mean a battle, which might well cause casualties among bystanders.

Mr. Faizi said the president was concerned that in many cases, Afghan families were forced to give food and shelter to insurgents, and then later were blamed for doing so and arrested. “We think that all these night raids, they bring the conflict directly to the homes of the Afghan people,” he said. “It has to be the opposite, the fight has to be fought somewhere else.”

U.S. Afghan strategy in disarray

The real meaning of occupation

Pakistan to boycott meeting on Afghanistan after NATO strike kills troops

Bloomberg reports: Pakistan stepped up its protests over a NATO airstrike that killed 24 of its soldiers, deciding to boycott an international conference on Afghanistan to be held in Germany next week.

The decision to pull out from the Dec. 5 summit in Bonn was agreed at a meeting of the federal Cabinet yesterday, according to a government statement. The nuclear-armed nation had already closed border crossings to trucks carrying supplies for U.S.-led forces in Afghanistan and ordered American personnel to vacate the Shamsi airbase in Pakistan’s southwest that has served as a launching point for Predator unmanned aircraft.

Pakistan still supports “stability and peace in Afghanistan and the importance of an Afghan-led, Afghan-owned process of reconciliation,” the government said in the statement. “In view of the developments and prevailing circumstances, the country has decided not to participate in the conference.”

The U.S. wants the Bonn meeting to cement a sustained international commitment to stabilize Afghanistan, and prevent any Taliban takeover, following the planned U.S. pullout of its main combat forces by 2014. The U.S. and Afghan governments have said Pakistan’s role is critical as it wields influence with the Taliban and could press the guerrillas for concessions in a peace process.

‘Beyond Rhetoric’Following the Nov. 25 airstrike, “there’s a lot of domestic pressure in Pakistan that’s forcing the government to move beyond rhetoric,” Shaheen Akhter, an analyst at the Institute of Regional Studies in Islamabad, said yesterday. Still, Pakistan can’t afford “to remain on the sidelines as the international community decides on the future of Afghanistan. They will be back at the table soon.”

The Economist‘s correspondent in Lahore notes: Pakistan’s leaders know the Americans are still deeply dependant on them. In the past few months NATO—and especially the Americans—have done an impressive job of reducing their reliance on land transport corridors through Pakistan to supply Western soldiers in Afghanistan. Over the past 120 days, for example, of the materiel received by the Americans in Afghanistan, around 30% was flown in and 40% was driven over Afghanistan’s northern borders from Central Asia, leaving just 30% to come via Pakistan’s roads. That is a sharp reduction on previous years. Thus the immediate and predictable closing of the Pakistan route, in response to the deaths on the border, should prove less disruptive than it once would have been.

But America relies on Pakistan in other ways. A military base, Shamsi, used by America inside Pakistan, apparently to launch drones, has been ordered closed within 15 days. That may be smoke and mirrors (it was quite possibly no longer used by the Americans anyway, after a previous clash), but is a sign of the sort of co-operation the Americans have quietly enjoyed on Pakistan’s account as they hunted al-Qaeda and other extremist leaders whom Pakistan does not regard as allies. Intelligence co-operation (however flawed) from Pakistan, against individuals plotting attacks on the West will also continue to be crucial in the coming years. Keeping close tabs on Pakistan’s large (perhaps 100-warhead strong) and fast-growing nuclear arsenal is also a long-term priority for the Americans.

Yet America and Pakistan could decide it is better to wind down their relationship to something minimal. A strong cohort within the Pentagon—especially after attacks on America’s embassy in Kabul, in September, by fighters seen as allied with Pakistan—has been demanding direct American military intervention in North Waziristan, possibly including American soldiers on the ground, even if Pakistan’s government opposes the idea. Pakistan is blamed for NATO and Afghan army forces’ failure to defeat the Taliban and other insurgents in Afghanistan, and for the Taliban’s refusal to consider peace talks. American lawmakers have also grown increasingly hostile over civilian and military aid to Pakistan, especially once it appeared that bin Laden had been harboured in Pakistan.

Within Pakistan, a breaking point could be near. One factor may be the rise of Imran Khan, a populist figure who makes a big deal of his opposition to America’s role in the ongoing fighting. As important may be the rise of younger, more religious army officers who are instinctively more anti-American than previous generals. After a year of crises and confrontations, the relationship, though troubled, survives. But the moment when one side or the other decides it is better to cut aid, reduce military co-operation and weaken diplomatic ties is growing nearer.