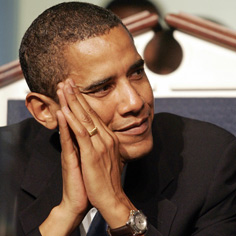

O bama cherishes the ideal of a frictionless transformation of society. It is a wish for aesthetic harmony, which he mistakes for a political goal. Its attainment would be a beautiful thing. But no matter how much he appeals for comity, Obama is certain to give offense to some. Better to choose your times and targets than allow others to force that choice.

bama cherishes the ideal of a frictionless transformation of society. It is a wish for aesthetic harmony, which he mistakes for a political goal. Its attainment would be a beautiful thing. But no matter how much he appeals for comity, Obama is certain to give offense to some. Better to choose your times and targets than allow others to force that choice.

His aversion to strife was plain from his conduct in the primaries and the general-election campaign. But the degree of avoidance we have seen could never have been predicted. Obama’s training, one recalls, was in the community-reform methods of Saul Alinsky; and yet he seems to have adapted the relevant ideas in foreshortened form. The Alinsky process of reform, as Jeffrey Stout has pointed out, goes from powerlessness to power in several stages. There is, first, the public recognition of powerlessness; then the airing of injustices, by legitimate polarization and active protest; then proposals of concrete reform; and only at last, power-sharing and reconciliation.

The strange thing about Obama is that he seems to suppose a community can pass directly from the sense of real injustice to a full reconciliation between the powerful and the powerless, without any of the unpleasant intervening collisions. This is a choice of emphasis that suits his temperament.

Reconciliation, however, can’t be genuine or lasting without some polarization, a careful (not generalized) exposure of injustices, and a fight that feels like a fight. In the absence of these, reconciliation dwindles into a rhetorical device; it leads to short-term salvation formulae and a renewal of discontents. The same objection applies to Obama’s wholly rhetorical notion that he can overcome the illegal actions of the Bush-Cheney administration by pardoning lower-echelon executors and “facing the future.” [continued…]