I n the early morning of October 8, 2007, a small group of British Greenpeace activists slipped inside a hulking smokestack that towers more than 600 feet above a coal-fired power plant in Kent, England. While other activists cut electricity on the plant’s grounds, they prepared to climb the interior of the structure to its top, rappel down its outside, and paint in block letters a demand that Prime Minister Gordon Brown put an end to plants like the Kingsnorth facility, which releases nearly 20,000 tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere each day.

n the early morning of October 8, 2007, a small group of British Greenpeace activists slipped inside a hulking smokestack that towers more than 600 feet above a coal-fired power plant in Kent, England. While other activists cut electricity on the plant’s grounds, they prepared to climb the interior of the structure to its top, rappel down its outside, and paint in block letters a demand that Prime Minister Gordon Brown put an end to plants like the Kingsnorth facility, which releases nearly 20,000 tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere each day.

The activists, most of them in their thirties and forties, expected the climb to the top of the smokestack would take less than three hours. Instead, scaling a narrow metal ladder inside took nine. “It was the most physically exhausting thing I have ever done,” 35-year-old Ben Stewart said later. “It was like climbing through a huge radiator — the hottest, dirtiest place you could imagine.”

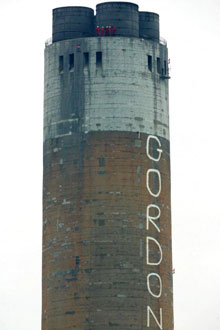

In the end, the fatigued, soot-covered climbers were only able to paint the word “Gordon” on the chimney before, facing dizzying heights, police helicopters, and a high court injunction, they were compelled to abandon the attempt and submit to arrest. They could hardly have known then that their botched attempt at signage would help transform British debate about fossil-fuel power plants — and that it would send tremors through an emerging global movement determined to use direct action to combat the depredations of climate change.

In the end, the fatigued, soot-covered climbers were only able to paint the word “Gordon” on the chimney before, facing dizzying heights, police helicopters, and a high court injunction, they were compelled to abandon the attempt and submit to arrest. They could hardly have known then that their botched attempt at signage would help transform British debate about fossil-fuel power plants — and that it would send tremors through an emerging global movement determined to use direct action to combat the depredations of climate change.

The case took on historic weight only after the Kingsnorth Six went to court, where they presented to a jury what is known in the United States as a “necessity” defense. This defense applies to situations in which a person violates a law to prevent a greater, imminent harm from occurring: for example, when someone breaks down a door to put out a fire in a burning building.

In the Kingsnorth case, world-renowned climate scientist James Hansen, director of the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies, flew to England to testify. According to the Guardian, he presented evidence that the Kingsnorth plant alone could be expected to cause sufficient global warming to prompt “the extinction of 400 species over its lifetime.” Citing a British government study showing that each ton of released carbon dioxide incurs $85 in future climate-change costs, the activists contended that shutting the plant down for the day had prevented $1.6 million in damages — a far greater harm to society than any rendered by their paint — and that their transgressions should therefore be excused.

What surprised both Greenpeace and the prosecution was that 12 ordinary Britons agreed. The jury returned with an acquittal, and the freed defendants made the front pages of newspapers throughout the country. The tumult also produced political results. In April, British energy and climate change minister Ed Miliband announced a reversal in governmental policy on power stations, declaring, “The era of new unabated coal has come to an end.” Discussing Kingsnorth, Daniel Mittler, a long-time environmental activist in Germany, told me recently, “it was probably one of the most impactful civil disobedience cases the world has ever seen, because it was the right action at the right time.” [continued…]