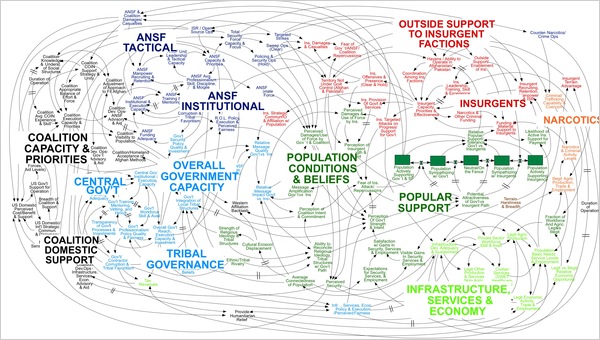

An article by Elisabeth Bumiller in the New York Times includes the diagram above. The illustration is indispensable for the lede — it does little to convey the principle failings of Powerpoint, least of all the cognitive style that Powerpoint engenders.

Gen. Stanley A. McChrystal, the leader of American and NATO forces in Afghanistan, was shown a PowerPoint slide in Kabul last summer that was meant to portray the complexity of American military strategy, but looked more like a bowl of spaghetti.

“When we understand that slide, we’ll have won the war,” General McChrystal dryly remarked, one of his advisers recalled, as the room erupted in laughter.

The slide has since bounced around the Internet as an example of a military tool that has spun out of control. Like an insurgency, PowerPoint has crept into the daily lives of military commanders and reached the level of near obsession. The amount of time expended on PowerPoint, the Microsoft presentation program of computer-generated charts, graphs and bullet points, has made it a running joke in the Pentagon and in Iraq and Afghanistan.

“PowerPoint makes us stupid,” Gen. James N. Mattis of the Marine Corps, the Joint Forces commander, said this month at a military conference in North Carolina. (He spoke without PowerPoint.) Brig. Gen. H. R. McMaster, who banned PowerPoint presentations when he led the successful effort to secure the northern Iraqi city of Tal Afar in 2005, followed up at the same conference by likening PowerPoint to an internal threat.

“It’s dangerous because it can create the illusion of understanding and the illusion of control,” General McMaster said in a telephone interview afterward. “Some problems in the world are not bullet-izable.”

In General McMaster’s view, PowerPoint’s worst offense is not a chart like the spaghetti graphic, which was first uncovered by NBC’s Richard Engel, but rigid lists of bullet points (in, say, a presentation on a conflict’s causes) that take no account of interconnected political, economic and ethnic forces. “If you divorce war from all of that, it becomes a targeting exercise,” General McMaster said.

Commanders say that behind all the PowerPoint jokes are serious concerns that the program stifles discussion, critical thinking and thoughtful decision-making. Not least, it ties up junior officers — referred to as PowerPoint Rangers — in the daily preparation of slides, be it for a Joint Staff meeting in Washington or for a platoon leader’s pre-mission combat briefing in a remote pocket of Afghanistan.

Last year when a military Web site, Company Command, asked an Army platoon leader in Iraq, Lt. Sam Nuxoll, how he spent most of his time, he responded, “Making PowerPoint slides.” When pressed, he said he was serious.

“I have to make a storyboard complete with digital pictures, diagrams and text summaries on just about anything that happens,” Lieutenant Nuxoll told the Web site. “Conduct a key leader engagement? Make a storyboard. Award a microgrant? Make a storyboard.”

Despite such tales, “death by PowerPoint,” the phrase used to described the numbing sensation that accompanies a 30-slide briefing, seems here to stay. The program, which first went on sale in 1987 and was acquired by Microsoft soon afterward, is deeply embedded in a military culture that has come to rely on PowerPoint’s hierarchical ordering of a confused world.

“There’s a lot of PowerPoint backlash, but I don’t see it going away anytime soon,” said Capt. Crispin Burke, an Army operations officer at Fort Drum, N.Y., who under the name Starbuck wrote an essay about PowerPoint on the Web site Small Wars Journal that cited Lieutenant Nuxoll’s comment.

In a daytime telephone conversation, he estimated that he spent an hour each day making PowerPoint slides. In an initial e-mail message responding to the request for an interview, he wrote, “I would be free tonight, but unfortunately, I work kind of late (sadly enough, making PPT slides).”

By Bumiller’s account, the military’s PowerPoint problem derives mostly from the ubiquity of its use, but as Edward Tufte, one of PowerPoint’s most ardent and cogent critics makes clear, the problem runs much deeper.

Imagine a widely used and expensive prescription drug that promised to make us beautiful but didn’t. Instead the drug had frequent, serious side effects: It induced stupidity, turned everyone into bores, wasted time, and degraded the quality and credibility of communication. These side effects would rightly lead to a worldwide product recall.

Yet slideware -computer programs for presentations -is everywhere: in corporate America, in government bureaucracies, even in our schools. Several hundred million copies of Microsoft PowerPoint are churning out trillions of slides each year. Slideware may help speakers outline their talks, but convenience for the speaker can be punishing to both content and audience. The standard PowerPoint presentation elevates format over content, betraying an attitude of commercialism that turns everything into a sales pitch.

Of course, data-driven meetings are nothing new. Years before today’s slideware, presentations at companies such as IBM and in the military used bullet lists shown by overhead projectors. But the format has become ubiquitous under PowerPoint, which was created in 1984 and later acquired by Microsoft. PowerPoint’s pushy style seeks to set up a speaker’s dominance over the audience. The speaker, after all, is making power points with bullets to followers. Could any metaphor be worse?

PowerPoint is packaged thought. The presenter has, supposedly, already done the required thinking and the audience is presented with the package on the understanding that the contents conform to the labeling. The PowerPoint spell is the illusion that a well-labelled package has valuable content when it may in fact turn out to be an empty box.

As Tufte concludes:

Presentations largely stand or fall on the quality, relevance, and integrity of the content. If your numbers are boring, then you’ve got the wrong numbers. If your words or images are not on point, making them dance in color won’t make them relevant. Audience boredom is usually a content failure, not a decoration failure.

At a minimum, a presentation format should do no harm. Yet the PowerPoint style routinely disrupts, dominates, and trivializes content. Thus PowerPoint presentations too often resemble a school play -very loud, very slow, and very simple.

The practical conclusions are clear. PowerPoint is a competent slide manager and projector. But rather than supplementing a presentation, it has become a substitute for it. Such misuse ignores the most important rule of speaking: Respect your audience.

It wasn’t the sharpest knifes in the drawer that passed up careers in all the high-tech and high-finance of the 1980s, going to West Point instead. Many of our current stock of Pentagon generals comes from the West Pont Class of 1976, a class apparently stained by involvement in a scandal about mass cheating on the engineering exam. Given the West Point Honor Code, this might have been the model for “Don’t ask, don’t tell.” Well, over the years these grads watched peers in the corporate world rob our national defense blind (45% of Federal revenue) and maybe now think, as their time as Pentagon retirees approaches, prospects for moving onto the boards of military-industrial-complex corporations must be established so they too can make up for lost time. I don’t know, but reading the military literature I and many of the scholars I check with are wondering “are they kidding?” when they see its intellectual quality. No, they’re not kidding, and one can note what happens when careers made on “yes sir” up chain of command to general staffs that McNamara and other Secretaries of Defense so disparaged what generals are really capable of. It all seems like creating money pits for corporations on whose boards the generals hope to retire. The first story about de-nuked ICMs followed by the chart that staff colonels put together to win the Afghan War may be giving us a clue as to where the generals are going after they retire and what’s coming up the ranks to replace them.

Excellent points here (power points?). The root of the PowerPoint failure is that it operates as if reality were strictly linear. I suspect it would be impossible to create a valid PPS for the mutually interacting elements of complex systems theory.

One must admire General McMaster’s reasoning on the failure in the military sphere. I wonder if there are ‘captains of industry’ who are smart enough to see the fallacies in their own worlds? We don’t need WW III or Global Warming to destroy the world — Microsoft is all ready on it.