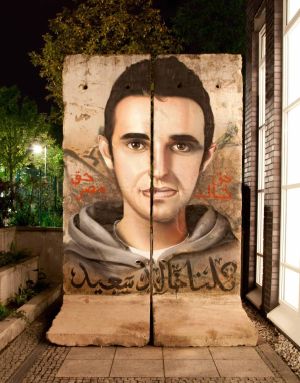

Amro Ali writes: On 6 June 2012, I will join countless others in commemorating the second anniversary of the death of Khaled Saeed, the twenty-eight-year-old Alexandrian who was beaten to death by plain-clothed policemen. The screams of Khaled echoed through Egypt and sparked the rapid countdown to the 2011 Egyptian Revolution.Khaled Saeed painting on the Berlin Wall by graffiti artist Andreas von Chrzanowski, photo by Joel Sames

Khaled was the neighbor down the street whom I, admittedly, paid little attention to. Yet his posthumous transformation from another face in the neighborhood to revolutionary poster child has become a source of both inspiration and concern. Inspiring in that he has given a focus and impetus to Egypt’s revolution, and concern in that his mythologization considerably conceals the real problems that the many “Khaled Saeeds” of Egypt face.

Khaled has been distorted almost beyond recognition. To understand the extent of this, based on interviews from friends, associates and my familiarity and understanding of the district, I attempt to provide a descriptive account of his life up until that fateful night in June 2010. The facts of his life are contrasted with his mythologization and the polarizing effects of both. His death was not just indicative of the corrupt and brutal police state; Khaled’s life was symptomatic of the widespread despair that continues to plague Egypt’s youth and that manifests in a plethora of symptoms from drug abuse to the strong desire to emigrate. The reconstruction of Khaled Saeed perpetuates self-defeating myths that, by elevating him into a figure with saint–like qualities, minimizes and simplifies the dynamics of his life that led up to his death.

Khaled’s tragedy was a turning point in my life. I first wrote about Khaled Saeed shortly after his death in an article titled, “Egypt’s Collision Course with History.” On the day Khaled died, I was in Australia reflecting on my late father who had died two years earlier on 6 June 2008, near to where Khaled passed away. When the news of Khaled’s death reached me, it shook my world. It was not just the manner of Khaled’s death that had disturbed me, but the deep reach of President Hosni Mubarak’s repressive police state into a neighborhood where I had grown up and idealized as a beacon of harmony. Up until then, I naively thought that such things happened to other people, in the slums, Islamist strongholds, in prisons, on the news, Alexandria’s rural outskirts, any “other area.” My area became that “other area.” [Continue reading…]

War in Context

… with attention to the unseen