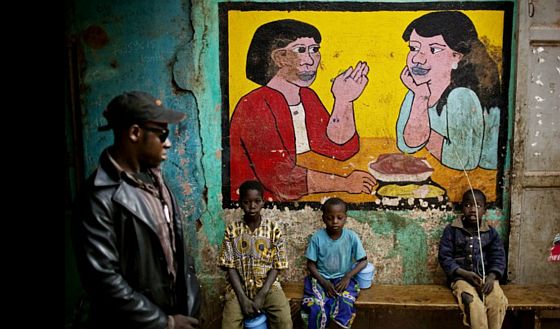

“Residents of the town of Niono, near the frontline, spend time outside a local restaurant,” says the caption to a photo appearing in the Washington Post on Sunday.

It wasn’t what the artist intended, but there turned out to be something prescient about depicting light-skinned people eating chicken in this dusty impoverished town in the Ségou Region of Mali.

Channel 4’s Lindsey Hilsum tweets:

The sole hotel in #niono #Mali served50+ journalists chicken for 3 days. Now we’ve all left. And all the chickens in town have bn eaten.

— Lindsey Hilsum (@lindseyhilsum) January 22, 2013

War correspondents always like to say they are near or at the frontline. The action gets confused with the story — even when reporters are perfectly aware that the audience back home (wherever that might be) is essentially none the wiser to be told that Islamist fighters have either advanced into or fled from Diabaly or whatever else the news of the day might be.

Telling the story of what’s happening in Mali doesn’t force the press to swarm around the charred remains left after each skirmish, yet war reporting is driven by imagery more than anything — images that convey the effects of violence but often little more.

If journalists didn’t insist on moving as a pack and took longer developing more informative stories, they might not end up depriving the locals of food that can hardly be spared.