Philip B. Corbett, who is in charge of The New York Times’s style manual and has the dubious title of associate managing editor for standards, is responsible for policing sentences like the following, which appeared in a February 8 article:

It turned out the activity was centered around a high school in Orange County.

Centered around? Goodness me. Mr. Corbett knows when a journalist needs a citation and so pulls out his rulebook where it says:

Centered around? Goodness me. Mr. Corbett knows when a journalist needs a citation and so pulls out his rulebook where it says:

center(v.). Do not write center around because the verb means gather at a point. Logic calls for center on, center in or revolve around.

Stan Carey, a linguist who unlike Corbett does not have his head stuck in the wrong place, points out the center around is an idiom and language isn’t geometry or logic. Corbett probably missed that tweet, or “twitter message,” as the Times insists on calling such pithy statements.

Meanwhile, I came across another lapse in the newspaper — one so commonplace among Americans that even the man in charge of “standards” at the Times probably sees no reason to correct it: the use of England and Britain as synonyms.

In “England Develops a Voracious Appetite for a New Diet,” Jennifer Conlin happily exchanges England and Britain, home of the British, in a way that those of us who hail from those parts and now live this side of the pond, know as all too familiar.

Explaining to an American that England and Britain are not the same, can end up feeling like providing an unsolicited tutorial in quantum physics. It’s an issue that probably lies far outside of the scope of the New York Times style guide.

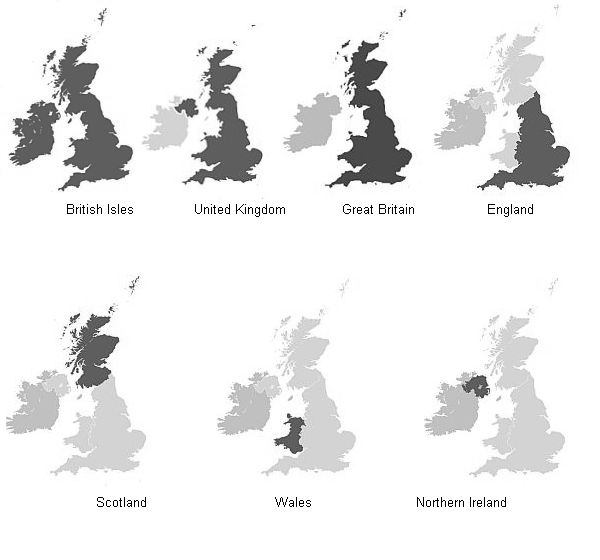

But for what it’s worth — and that probably isn’t much — I put together a nifty graphic for those readers who have an interest and would not be at risk of mistaking the British Isles for a Rorschach blot.

And to round off the picture with a few small caveats: Britain, the UK, and United Kingdom are synonyms for the sovereign state that belongs to the European Union. Its citizens are British, though Catholics in Northern Ireland generally identify themselves as Irish. There are British who identify themselves as either English, Welsh, Scottish, Irish or none of the above. And some of the above don’t identify themselves as British.

Is that all clear? I can’t for the life of me understand why Americans find this confusing!

(Just in case anyone suspects that my omission of the labeling of the Republic of Ireland from this graphic represents some kind of British prejudice — far from it. I wouldn’t want to insult the Irish by including them in a parsing of the meaning of British.)