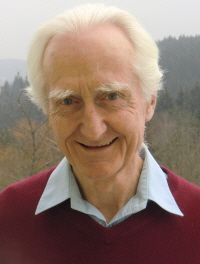

Christopher Dickey reports: The new pope won over the crowd in St. Peter’s Square on Wednesday night with his kindly voice and humble words. But whispers about his past hover like a threatening storm over his papacy. When Jorge Mario Bergoglio, now Pope Francis, was the head of the Jesuit order in Argentina, did he do too little to protect his priests from a savage military dictatorship? Or, worse, did he denounce some of them as guerrilla sympathizers, virtually sentencing them to death?Franz Jalics SJ

The allegations are not new, but they are persistent.

“It was the time of the civil war between the extreme right-wing and left-wing groups in Argentine society,” wrote Franz Jalics, an Argentine priest [correction: he’s Hungarian], looking back decades later. It was 1976, and after years of growing violence by various guerrilla groups, a military junta had seized power in Buenos Aires. The secretive campaign waged by the generals, known as the “dirty war,” was ferocious. Thousands of people were “disappeared” at the hands of a special Navy unit that took some prisoners to concentration camps and threw others into the sea from helicopters.

One Sunday morning the unit came for Jalics and another Jesuit priest, Orlando Yorio. Rumor had it that the two were sympathetic to the guerilla groups. An influential member of the local Catholic hierarchy had apparently confirmed that information to the junta.

Their tormentors used drugs and torture to try to make them talk. For five months, blindfolded and chained the whole time, the priests lived in terror, convinced that at any second they’d be killed. “My fears don’t seem exaggerated to me even today,” Jalics wrote, nearly 20 years later. When the dictatorship ended and several commanders were put on trial, he wrote, “there were no surviving witnesses from the 6,000 people whom this particular group had abducted. Only we two survived. All the others had been killed.”

In Jalics’s book, first published in 1994, he writes about the intense rage he felt against the man (unnamed) he believed had betrayed him in meetings with the military. More recently Argentine muckraker Horacio Verbitsky reported in a series of detailed articles and in his own book that the betrayer was Bergoglio, head of the Jesuit order in Argentina at the time. Verbitsky bases that allegation on interviews with Yorio, who died of natural causes in 2000, and on several documents.

Jalics does not name the object of his rage himself, and appears never to have confirmed Verbitsky’s reports publicly. Why? Perhaps because, as Jalics writes, he forgave his enemy as Christians are supposed to do.

Bergoglio’s fellow cardinals certainly knew about the allegations, but chose not to believe them when they voted for him to be pope. Australia’s Cardinal George Pell told a television interviewer on Thursday: “Those stories were dismissed years ago. They were a smear and a lie. They were laid to rest years ago.”

Not really. As recently as October 2012, Argentina’s bishops under Bergoglio’s leadership issued a collective apology for failing to protect their flock adequately during the dictatorship, blaming both the right-wing generals and the left-wing guerrillas for the years of bloodshed. The Daily Beast’s Mac Margolis reports from Rio de Janeiro that Bergoglio’s biographer, Sergio Rubín, has been defending the new pope in the press by claiming that his “nonconfrontational” attitude toward the junta was pragmatism at a time when many people were being persecuted, tortured, and killed.

As Rubín tells the story, Bergoglio persuaded the chaplain of the junta’s leader to call in sick so Bergoglio could go to the general’s home to say Mass and raise the question of the abducted priests personally. Rubín argues that Bergoglio’s later reluctance to talk about his role during the dirty war is a sign of “humility.”

“What is a well-established point is that the leadership of the Catholic Church in Argentina during the dictatorship was pretty much silent,” says José Miguel Vivanco, director of the Americas division at Human Rights Watch in New York. He won’t comment on the allegations against the new pope, but acknowledges that “some bishops were openly sympathetic to the military junta.”

Jalics’s humble little book is not an exposé like Verbitsky’s, it is not a smear, and it does not read like a lie. I bought it on Thursday morning in the “spirituality” section of a store run by nuns a couple of blocks from St. Peter’s Square. Its title is Contemplative Retreat: An Introduction to the Contemplative Way of Life and to the Jesus Prayer.

Only six of the book’s 332 pages deal with Jalics’s experiences in 1976 and what happened to him afterward, and he tells the story as an example of the power of contemplation, the importance of forgiveness. The entire grim experience, he claims, was a source of “purification.”

“I went to this particular person to tell him that he was playing with our lives. The man promised me he would communicate to the military that we were not terrorists.” [Continue reading…]

War in Context

… with attention to the unseen