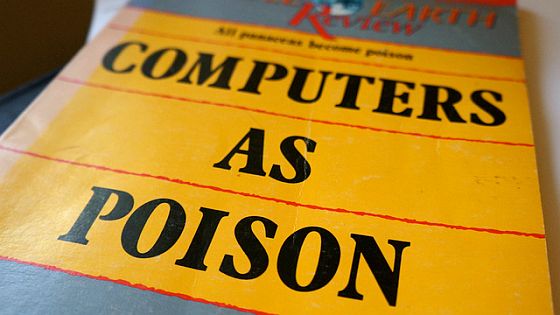

The cover of Whole Earth Review, January, 1985

The Boston Globe’s Ideas section: In the mid 1980s, when Mark Zuckerberg was still in diapers, computers ran on floppy disks, and a web was something a spider built, a computer-science graduate student at Yale University started to worry about a problem that would have struck most people as far-fetched.

Larry Hunter began to realize that as computers became bigger parts of our lives, they would come to know more and more about us, whether we liked it or not. They would gather data and build profiles, and this technology would someday have meaningful implications for our privacy and freedom of choice.

In January 1985 he published a warning essay in the inaugural issue of a techno-revolutionary journal called The Whole Earth Review. “The ubiquity and power of the computer blur the distinction between public and private information,” he wrote. “Our revolution will not be in gathering data — don’t look for TV cameras in your bedroom — but in analyzing information that is already willingly shared.”

In just the past few years, Hunter’s concerns — recently unearthed and reposted on the Smithsonian Magazine’s Paleofuture blog — have come to look almost spookily prescient. His solution, however — new laws to give people property rights over their information — has never come to pass. Today, every time we click a link, shop on Amazon, or retweet a news story, we offer the vast digital world one more free clue about who we are and what we like. All this information is stored and analyzed, bought and sold — last week, it emerged that the FBI and National Security Agency have been collecting this data directly from some of the largest Internet companies. The scope of our private lives is shrinking, and we still don’t really know the implications of this shift.

Hunter is now a professor of computational biology at the University of Colorado Denver, where he creates software that pulls together distant strands of biomedical research. Though he has also kept a finger in the privacy debate, his personal positions on privacy aren’t necessarily what you might think: He encrypts e-mails to friends and extols the privacy benefits of all-cash transactions, but he’s also posted his genetic data online.

Ideas reached out to him for his perspective on how the last 30 years have unfolded, and to ask what he sees as the next big privacy concerns. This transcript was edited from interviews by phone and e-mail. [Continue reading…]

“Hunter is now a professor of computational biology at the University of Colorado Denver, where he creates software that pulls together distant strands of biomedical research. In a recent interview he was quoted as saying “I told you so.””