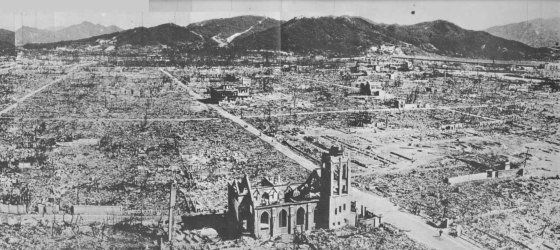

Hiroshima, August, 1945

The testimony of those who have fought in war is filled with accounts about gruesome acts that few individuals could ever have imagined engaging in or witnessing in any other circumstances. War opens up dark realms that don’t even enter the nightmares of those who have never been there. The more horrific the event, the more haunting the memory — or at least, so one might expect.

Sixty-eight years after the first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, Greg Mitchell looks back at the experiences of some of those who were involved.

Never before, nor subsequently, has there been an act of genocide in human history where so many people have been slaughtered in such a brief span of time.

At 8.15 am, local time, on August 6, 1945, Colonel Paul W. Tibbets unleashed the greatest force of human destruction ever devised, while piloting an aircraft to which the personal touch had been added: his mother’s name — the Enola Gay.

Forty years after the event, Mitchell spoke to Tibbets and they talked about his experience. But prior to that conversation, Mitchell visited Hiroshima.

While spending a month in Japan on a grant in 1984, I met a man named Akihiro Takahashi. He was one of the many child victims of the atomic attack, but unlike most of them, he survived (though with horrific burns and other injuries), and grew up to become a director of the memorial museum in Hiroshima.

Takahashi showed me personal letters to and from Tibbets, which had led to a remarkable meeting between the two elderly men in Washington, D.C. At that recent meeting, Takahashi expressed forgiveness, admitted Japan’s aggression and cruelty in the war, and then pressed Tibbets to acknowledge that the indiscriminate bombing of civilians was always wrong.

But the pilot (who had not met one of the Japanese survivors previously) was non-committal in his response, while volunteering that wars were a very bad idea in the nuclear age. Takahashi swore he saw a tear in the corner of one of Tibbets’ eyes.

So, on May 6, 1985, I called Tibbets at his office at Executive Jet Aviation in Columbus, Ohio, and in surprisingly short order, he got on the horn. He confirmed the meeting with Takahashi (he agreed to do that only out of “courtesy”) and most of the details, but scoffed at the notion of shedding any tears over the bombing. That was, in fact, “bullshit.”

“I’ve got a standard answer on that,” he informed me, referring to guilt. “I felt nothing about it. I’m sorry for Takahashi and the others who got burned up down there, but I felt sorry for those who died at Pearl Harbor, too…. People get mad when I say this but — it was as impersonal as could be. There wasn’t anything personal as far as I’m concerned, so I had no personal part in it.

“It wasn’t my decision to make morally, one way or another. I did what I was told — I didn’t invent the bomb, I just dropped the damn thing. It was a success, and that’s where I’ve left it. I can assure you that I sleep just as peacefully as anybody can sleep.” When August 6 rolled around each year “sometimes people have to tell me. To me it’s just another day.”

One of the other aircraft on the mission to bomb Hiroshima, at the time unnamed, was later named Necessary Evil — a response presumably to what had become the conventional wisdom: that as horrific as the use of nuclear weapons had been, their use had been necessary as the means to bring to an end the Second World War. The lives lost in Hiroshima and Nagasaki prevented even greater loss of life, had the war dragged on — so the argument goes.

But as Ward Wilson has persuasively argued, it was not the nuclear destruction of two of its cities that led Japan to surrender; it was instead the Soviet Union’s decision to invade.

The Soviet invasion invalidated the military’s decisive battle strategy, just as it invalidated the diplomatic strategy. At a single stroke, all of Japan’s options evaporated. The Soviet invasion was strategically decisive — it foreclosed both of Japan’s options — while the bombing of Hiroshima (which foreclosed neither) was not.

For many of those involved, war, seemingly driven by necessity, closes off the faculty of choice and where there is no sense of choice, there is little sense of responsibility.

Those who look back and question their own actions are implicitly considering the possibility that they could have acted otherwise.

Though it’s often said that truth is the first casualty of war, what keeps the war machine in perpetual motion is the conviction: we have no choice.

Evil it was, but not necessary — at least, not for ending the war.

But it should be remembered that WWII was a “total war” — meaning that all the rules and protocols of war were out the window. Or as the guys like to say, “the gloves came off.”

This image of Hiroshima reminds me of that famous image of firebombed Dresden — also a war crime against a city that never made anything more dangerous than dinner plates. In total war, in which civilians are the intended targets of bombing rather than ‘‘merely” collateral damage, war and genocide collapse into each other: liberators become perpetrators, and bystanders become victims. 60 million people lost their lives in WWII. That’s evil.

And this is one of the many reasons why international law declares war to be the greatest crime of all and always illegal, except when deemed necessary by the UN Security Council.

Remember the UN? That 100-year experiment in peace rendered “irrelevant” by American ambitions to empire?