Reem Salahi writes: Traveling into “liberated” (i.e. rebel-controlled) Syria, I was initially struck by the appearance of normality. Olive groves bloomed, kids played on the street and food and drink stands peppered the roadways. Absent were the pictures and statutes of Bashar and his father Hafez al-Assad that I had come to expect from my many trips to Syria. Also missing were the regime flags and any other sign of Baathist rule.

The deeper we went into Syria, though, the more abnormal things became. Tinted and unlicensed SUVs with the insignia of a Free Syrian Army (FSA) or Islamist brigade were readily prevalent. Men with guns strapped to their backs wearing military fatigues and long beards rode on motorcycles. Demolished factories and bombed stores were more frequent sights than open and functioning stores. And FSA checkpoints secured the entry and exit points of most towns. As we drove deeper into Idlib Province, I found myself thinking of Dorothy’s line in the Wizard of Oz: “Toto, I’ve a feeling we’re not in Kansas anymore.”

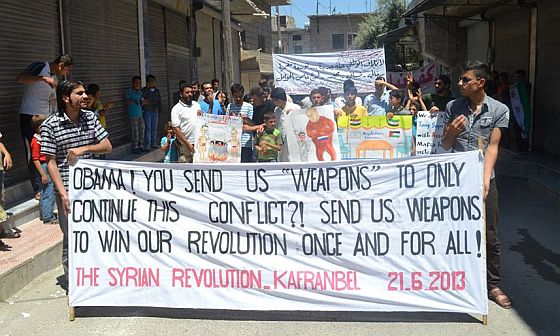

Entering Kafranbel — a small yet internationally-known town due to its witty posters and weekly protests — I was awestruck by the painted walls with messages of “rEVOLution”.

The media center was abuzz with foreign journalists and local activists as they prepared their posters for the Friday protest. The English and Arabic posters as well as the drawings depicting Barack Obama and Vladimir Putin were calculated to speak to local and global audiences. The activists spent hours strategizing how best to express their dissatisfaction with the U.S.’s failure to provide anti-aircraft missiles and heavy weaponry that could strike down government planes that terrorized the “liberated” areas.

Yet in the subsequent days, I experienced the more honest banality of life. Despite not having a physical presence in the “liberated” areas, the government still controlled the utilities and cut the electricity for 20 or more hours a day as both a carrot (a reminder that it remained in power) and a stick. There was no phone service and Internet was rare; jobs were even rarer. At times, it seemed that the only activity was in the sky from helicopters transporting soldiers or dumping loads of explosives on “liberated” towns or in the hospitals that assumed the consequent casualties.

As we lazily sat around during the long hot summer days drinking one cup of sweetened tea after another and doing little else, I was surprised to hear Syrians state they had “no time.” I soon understood that it was not the physical demand for time but the lack of mental clarity for solutions to the intractable conflict that had left Syrian towns with no formal governance and little resources; their residents, without exception, were left psychologically scarred and emotionally taxed. As one young man expressed to me: “everyone wants to train me in transitional justice and documenting human rights abuses but no one has offered to train me on how to overthrow the Regime. It’s been over two years and I still don’t know how to do the very thing that got me involved in this Revolution in the first place.” [Continue reading…]