Michael Korda, author of a new biographer of TE Lawrence, Hero: The Life and Legend of Lawrence of Arabia, writes:

Lawrence fought against the Sykes-Picot Agreement, attempted to undermine it, drove the Arabs on in a desperate race to capture Damascus and declare an independent Arab state before the British Army could get there, argued against the Sykes-Picot Agreement vehemently with Wilson, Lloyd George, and Clemenceau after the war in Paris at the peace conference, as well as face to face with King George V at Buckingham Palace, and with the Marquess of Curzon at the War Cabinet. Even at the most courageous and daring moments of his service in the desert, Lawrence was gnawed by these doubts. When he rode off to enter Damascus in 1917, alone and with a price on his head, he wrote an agonized note to his chief in Cairo: “Clayton, I’ve decided to go off alone to Damascus, hoping to get killed on the way… We are calling them to fight for us on a lie, and I can’t stand it.”

It was his view then and later that the Allies had persuaded the Arabs to take up arms against the Turks with a false promise, and that even as the Arabs were fighting, the British and the French were secretly laying claim to the spoils of war in advance, and sharing between themselves the areas that the Arabs had been promised: Lebanon and Syria for France, Palestine, what is now Jordan, and what is now Iraq (with its rich oil reserves) for Great Britain, leaving for the Arabs only a few worthless strips of desert, without major ports or sensible frontiers, like throwing them the carcass of a chicken once the meat had been carved away.

It was not shame at having been beaten and gang-raped by the Turks when he was briefly captured at Deraa (fortunately for Lawrence, they did not recognize him) that caused him to refuse the Distinguished Service Order and the insignia of a Companion of the Bath from the hands of King George V, and also the king’s offer of a knighthood or the Order of Merit. Rather it was Lawrence’s guilt over the fact that the Allies had broken their promises to the Arabs that led him to reject all honors, give up his rank, and join the Royal Air Force in 1922 as an aircraftman second class, the equivalent of a private, under an assumed name, “solitary in the ranks.”

It is not necessary to agree with the Arab point of view about their own history, but it is foolish to ignore it. In the eyes of Arabs, the West (including the United States, which acquiesced to the brutal and cynical British and French partition of the Middle East) is responsible for the fragmented reality of the area today, and for its artificial frontiers. This is the unforgivable “original sin” to Arabs, and the subsequent partition of Palestine is merely a further extension of it, exacerbating wounds that were already there.

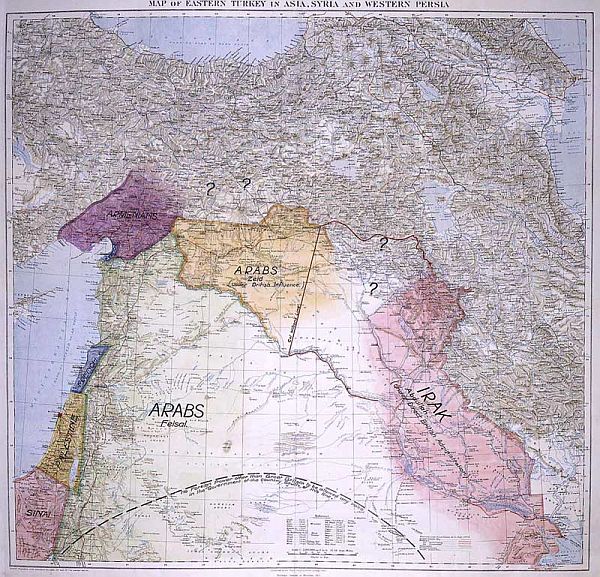

Many of the problems that exist in the area—including, but by no means limited to Syrian-armed interference in Lebanon, the failure to create a viable “Kurdistan” for the Kurd people, the hostility between Arabs and Jews in Palestine, the future of the West Bank—were addressed by Lawrence in the map [see below] he prepared for the British War Cabinet and the Paris Peace Conference, but brushed under the table by the great powers. Indeed, it is typical of Lawrence that he managed to get Prince Feisal, the leader of the Arab Revolt, and Chaim Weizmann, the Zionist leader, to sit down together in January 1919 and sign an extraordinary agreement (largely drafted by Lawrence himself) that would have created a joint Arab-Jewish government in Palestine, with unlimited Jewish immigration. Feisal conceded that Palestine could contain 4 million to 5 million Jewish immigrants without harm to the rights or property of the Arab population, a number not greatly different from the number of Jews living in Israel today. Had Wilson, Clemenceau, and Lloyd George been willing to agree to Arab demands, an Arab-Jewish state might have existed that could have absorbed the bulk of the European Jews whom the Germans would slaughter between 1933 and 1945, as well as producing a state with advanced agriculture, industry, and education, in which Jews and Arabs might have proved that they could live together peacefully and productively.

Well, here we are almost 100 years later, with the same old Western influence, yet no solution. Considering all that could have been, yet today, stands on the brink of being poisoned by Nuclear fall out, just proves that when the powers of the West try to impose ideas of their own making, no concrete progress will be made. The fact that the West exploited the resources hasn’t helped. Perhaps the biggest blunder though, has been the U.S. stance of backing the Israeli’s in their drive to hold onto what they received by the British after W.W.II. Their continuing regression from being the victim as they were from the Holocaust, to being cut from the same cloth as the Nazi’s, isn’t winning friends & influencing others. One would think that instead of trying to bully everybody from the sand box, they would instead share the tools to bring about peace. Dragging the U.S. into their open madness, especially their controlling the U.S.Government as they do today, from a shadow point of view, is really treasonous to both countries as well as to the peoples of the Middle East. I believe the mind set caused by the Nazi’s caused a permanent fault in the present views.

The only point I’d disagree with Norman, about “dragging the US into their madness”. Seems to me we do it freely and step along at a rapid pace to do so.

“it is typical of Lawrence that he managed to get Prince Feisal, the leader of the Arab Revolt, and Chaim Weizmann, the Zionist leader, to sit down together in January 1919 and sign an extraordinary agreement (largely drafted by Lawrence himself) that would have created a joint Arab-Jewish government in Palestine, with unlimited Jewish immigration.”

This sounds like a historical fabrication. According to Lowell Thomas, Lawrence’s 1924 biographer , Feisal agreed to nothing of the sort. Besides there were almost no Jews in 1919 who had any desire to live in Palestine. So this plan, if it existed at all, could have come to nothing. Lawrence, for all his ambivalences, is best remembered as a man who greatly admired the Arabs and regretted the treachery of the French and British in dealing with them. Today we can add to that account the treachery of the Americans.