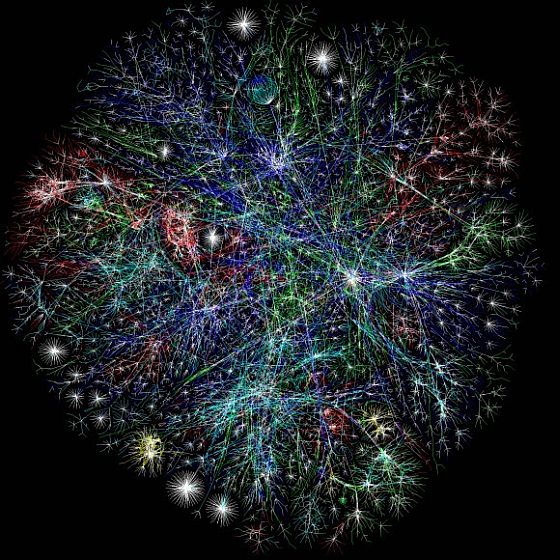

A 2003 map of the internet created by the Opte Project.

I don’t make it a habit to copy and paste whole articles. Instead, I generally engage in an informal exchange — take an extract and send some readers to the source. It seems like an equitable arrangement. But once in a while a piece just seems too good to break apart and so I take the liberty of re-posting it from beginning to end.

On a weekend when there was a torrent of posts responding to the death of Aaron Swartz, an obituary by Brendan Greeley stood out for me. It serves as an eloquent reminder about how the internet came into existence and what allows it to function.

The Internet is not so old. Its graybeards live still. Vint Cerf, author of the Internet Protocol, has been installed as Google’s “chief Internet evangelist,” a ceremonial title he chose himself. Tim Berners-Lee, who gave us HTML, has been knighted. He now sits at the head of his own foundation at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, a guardian of the language he wrote. And languages are the best way to think of these contributions.

The Internet is a voluntary agreement, a group of languages we’ve all decided to have in common. The Internet Protocol allows computers to talk to each other. You could use a different language, but since the rest of the world already speaks IP, you’d be lonely, speaking only to yourself.

When he was barely a teenager, Aaron Swartz began playing with XML, an Internet language like Sanskrit or classical Greek—flexible, elegant, and capable of great complexity. XML is most often used to move large amounts of information, entire databases, among computers. You open XML by introducing new terms and defining what they’ll do, nesting new definitions inside of those you’ve already created. Of this, Swartz created a kind of pidgin, a simple set of definitions called RSS.

Before RSS, the Web was static, a place of bookmarks. You had to go to a site to see what was new. Swartz’s pidgin made it easy for updates to travel among websites. If you see a box on a Web page that reads “new headlines,” those headlines very likely arrived on the back of an RSS feed. At the age of 14, Swartz made the Web move. He committed suicide on Jan. 11 at the age of 26.

Swartz was not the only author of RSS. Dave Winer, also often credited with the standard, wrote his own remembrance of Swartz; he also linked to his own chronology of the development of RSS, which does not mention Swartz at all. This uncertainty is endemic of the way the Internet moves forward. Its greatest advances have come from smart people trying to solve the same problem for free, together or at odds, and often in the orbit of a university. As a teenager, Swartz hung out at the Berkman Center for Internet and Society at Harvard Law School, where Winer was also later a fellow.

Commercial empires rely on these advances. Then they attempt to own them. When Apple decided to start accepting RSS as a way to get podcasts into iTunes, it marched all over the standard, muddying it with its own mostly superfluous Apple-centric definitions. It had the power to do this, back when it owned the market for portable MP3 players. Apple did not invent RSS or podcasting, but it has won mightily from the work of Swartz and Winer. Twitter was founded as a podcasting company. It later used RSS as one of the ways to distribute its messages.

This is the tension at the heart of the Internet: whether to own or to make. You can own a site or a program — iTunes, Microsoft Word, Facebook, Twitter — but you can’t own a language. Yet the languages, written for beauty and utility, make sites and programs useful and possible. You make the Internet work by making languages universal and free; you make money from the Internet by closing off bits of it and charging to get in. There’s certainly nothing wrong with making money, but without the innovations of complicated, brilliant people like Swartz, no one would be making any money at all.

RSS was just one of Swartz’s accomplishments. He helped found Reddit, a social networking site. He could have been Mark Zuckerberg, and the two traveled in the same circles in Cambridge, Mass. But where Zuckerberg built an empire, Swartz kept looking for fights. He challenged the practice of charging to download case law, which sits in the public domain. He snuck into a closet at MIT with a laptop and used the university’s connection to download much of the archive of JSTOR, a fee-based catalogue of journal articles, many written by taxpayer-funded academics. The Department of Justice prosecuted him for this; his family believes the harassment played a part in his death.

Swartz wasn’t an anarchist. He came to believe that copyright law had been abused and was being used to close off what, by law, should be open. It’s hard to find fault with his logic, and there’s much to admire in a man who, rather than become a small god of the Valley, was willing to court punishment to prove a point. The world will have no trouble remembering Steve Jobs and Mark Zuckerberg, and this is as it should be. But it should remember, too, people like Aaron Swartz, the ones who make those empires possible.

–

very sad this and unnecessary

26 is not enough, by any stretch

and to think at 15 i was up at the uni vermont [’72]

with curt, showing me basic, cobol and fortran etc …

yellow ticker tape and ibm punch cards

‘don’t drop, that stack of cards !’

he’s at harvard now, complex analysis

and three dimensional representation

he always did love escher and chess

we ‘coulda had a micro-soft or apple

of course i ‘woulda been the one

that loved jimi hendrix, no doubt

we should be encouraging this talent

not prosecuting it – shame on us

–