Jackson Lears reviews Inside the Centre: The Life of J. Robert Oppenheimer by Ray Monk: Reasonable men can dream monstrous dreams. It is the lesson of the 20th century: a lesson articulated from various perspectives since Adorno and Horkheimer wrote Dialectic of Enlightenment amid the wreckage of World War Two. Defenders of the Enlightenment can cogently argue (and many have) that Nazi science was a grotesque caricature, that the Holocaust was a betrayal of the Enlightenment rather than a fulfilment of its fatal dialectic. But it is harder to make that case with respect to the development of nuclear weapons. Indeed the subject seems designed to lay bare the contradictions at the core of Enlightenment culture by revealing them at work in the subculture of professional physicists bent to the needs of government power. Few social laboratories could more clearly reveal the tensions between chauvinist impulses and humanist aspirations, or between careerist plotting and disinterested service, or – perhaps most important – between the Enlightenment ideal of intellectual openness and the demands for secrecy made by the national security state.

The history of nuclear weapons began in an atmosphere of creative ferment and international trade in ideas. This was the world of Knaben3physik (‘boy physics’) in the 1920s and 1930s, when young men who had not been shaving for more than a few years were excitedly reading one another’s papers and poring over the results of experiments in Cambridge, Göttingen, Copenhagen and (eventually) Berkeley. This was how Niels Bohr, Werner Heisenberg and others created the foundations of quantum physics. Yet within less than a decade this moment had passed. Olympian conversations were drowned out by fascist chants. Jewish physicists, led by Einstein, fled to America; Heisenberg stayed in Germany; Bohr stayed out of sight in occupied Denmark. The concentration of research effort shifted westwards across the Atlantic. But it was research with a new, pragmatic mission: to build an atomic bomb before Hitler did. Theories conceived in open exchange were harnessed to secret purposes, and illuminating ideas were pressed into the service of mass death. No wonder some of the atomic scientists felt remorse, or at least ambivalence, about their achievement; no wonder some began to glimpse the darker dimensions of Enlightenment when the blinding flash of the first atomic explosion revealed their labours had not been in vain.

J. Robert Oppenheimer, the physicist in charge of the Manhattan Project and hence ‘father of the atomic bomb’, was never openly remorseful. But he was nothing if not ambivalent, as Ray Monk makes clear in his superb biography. When the fireball burst Oppenheimer remembered the words from Vishnu in the Bhagavad Gita: ‘I am become death, destroyer of worlds.’ It was his own idiosyncratic translation, and it became his most famous remark. The next day, though, his mood was anything but sombre as he jumped out of a jeep at Los Alamos base camp. His friend and fellow physicist Isidor Rabi said: ‘I’ll never forget the way he stepped out of the car … his walk was like High Noon … this kind of strut. He had done it.’ His colleague Enrico Fermi ‘seemed shrunken and aged, made of old parchment’ by comparison. Yet his euphoria passed, and he sank into second thoughts, despondent about the calamitous consequences awaiting the Japanese. He walked the corridors mournfully, muttering: ‘I just keep thinking about all those poor little people.’ Racial condescension aside, he meant what he said, and during the days following the test his secretary said he looked as though he were thinking: ‘Oh God, what have we done!’ [Continue reading…]

Category Archives: nuclear issues

Video: Is a nuclear-free Middle East possible?

Twelve terrifying tales from the nuclear crypt

Jeffrey Lewis writes: October is a scary month. And it’s not just Halloween. October also happens to be the anniversary of the Cuban Missile Crisis. And if the ghosts and goblins don’t make you wet your pants, the thought of Khrushchev, Kennedy, and Castro dancing on the edge of nuclear war should.

During the Cold War, the United States twice more raised the alert status of its nuclear forces — in October 1969 and October 1973. And one of the worst reactor accidents at a military program — the fire at Britain’s Windscale reactor — also happened in October.

You might start to think there is something particularly dangerous about October. But the reality is that there have been so many accidents, false alarms, and other mishaps involving nuclear weapons that you haven’t heard about — and every month contains at least one seriously scary incident. The Department of Defense has released narrative summaries for 32 accidents involving nuclear weapons between 1950 and 1980, many of which involve aircraft bearing bombs. False alarms? Please. The Department of Defense admitted 1,152 “moderately serious” false alarms between 1977 and 1984 — roughly three a week. (I love the phrase “moderately serious.” I wonder how many “seriously serious” false alarms they had?) I kind of get the feeling that if NORAD went more than a week without a serious false alarm, they would start to wonder if the computers were ok.

The hard part was choosing the most frightening moments. There is no reason to believe the apocryphal story about the British Army choosing red uniforms because they do not show blood. But after 60-odd years of nuclear accidents, incidents, and whatnot, I can recommend that the STRATCOM commander consider brown pants.

So, here’s my list of 12 seriously scary events, one for each month. This list is not comprehensive, nor is it intended to be the worst events. [Continue reading…]

Thank you Vasili Arkhipov, the man who stopped nuclear war

Edward Wilson writes: If you were born before 27 October 1962, Vasili Alexandrovich Arkhipov saved your life. It was the most dangerous day in history. An American spy plane had been shot down over Cuba while another U2 had got lost and strayed into Soviet airspace. As these dramas ratcheted tensions beyond breaking point, an American destroyer, the USS Beale, began to drop depth charges on the B-59, a Soviet submarine armed with a nuclear weapon.

The captain of the B-59, Valentin Savitsky, had no way of knowing that the depth charges were non-lethal “practice” rounds intended as warning shots to force the B-59 to surface. The Beale was joined by other US destroyers who piled in to pummel the submerged B-59 with more explosives. The exhausted Savitsky assumed that his submarine was doomed and that world war three had broken out. He ordered the B-59’s ten kiloton nuclear torpedo to be prepared for firing. Its target was the USS Randolf, the giant aircraft carrier leading the task force.

If the B-59’s torpedo had vaporised the Randolf, the nuclear clouds would quickly have spread from sea to land. The first targets would have been Moscow, London, the airbases of East Anglia and troop concentrations in Germany. The next wave of bombs would have wiped out “economic targets”, a euphemism for civilian populations – more than half the UK population would have died. Meanwhile, the Pentagon’s SIOP, Single Integrated Operational Plan – a doomsday scenario that echoed Dr Strangelove’s orgiastic Götterdämmerung – would have hurled 5,500 nuclear weapons against a thousand targets, including ones in non-belligerent states such as Albania and China.

What would have happened to the US itself is uncertain. The very reason that Khrushchev sent missiles to Cuba was because the Soviet Union lacked a credible long range ICBM deterrent against a possible US attack. It seems likely that America would have suffered far fewer casualties than its European allies. The fact that Britain and western Europe were regarded by some in the Pentagon as expendable pawn sacrifices was the great unmentionable of the cold war.

Fifty years on, what lessons can be drawn from the Cuban missile crisis? One is that governments lose control in a crisis. [Continue reading…]

Cuban missile crisis: how the U.S. played Russian roulette with nuclear war

Noam Chomsky writes: The world stood still 50 years ago during the last week of October, from the moment when it learned that the Soviet Union had placed nuclear-armed missiles in Cuba until the crisis was officially ended – though, unknown to the public, only officially.

The image of the world standing still is due to Sheldon Stern, former historian at the John F Kennedy Presidential Library, who published the authoritative version of the tapes of the ExComm meetings where Kennedy, and a close circle of advisers, debated how to respond to the crisis. The meetings were secretly recorded by the president, which might bear on the fact that his stand throughout the recorded sessions is relatively temperate, as compared to other participants who were unaware that they were speaking to history. Stern has just published an accessible and accurate review of this critically important documentary record, finally declassified in the 1990s. I will keep to that here. “Never before or since,” he concludes, “has the survival of human civilization been at stake in a few short weeks of dangerous deliberations,” culminating in the Week the World Stood Still.

There was good reason for the global concern. A nuclear war was all too imminent – a war that might “destroy the Northern Hemisphere”, President Eisenhower had warned. Kennedy’s own judgment was that the probability of war might have been as high as 50%. Estimates became higher as the confrontation reached its peak and the “secret doomsday plan to ensure the survival of the government was put into effect” in Washington, described by journalist Michael Dobbs in his recent, well-researched bestseller on the crisis – though he doesn’t explain why there would be much point in doing so, given the likely nature of nuclear war. Dobbs quotes Dino Brugioni, “a key member of the CIA team monitoring the Soviet missile build-up”, who saw no way out except “war and complete destruction” as the clock moved to One Minute to Midnight – Dobbs’ title. Kennedy’s close associate, historian Arthur Schlesinger, described the events as “the most dangerous moment in human history”. Defense Secretary Robert McNamara wondered aloud whether he “would live to see another Saturday night”, and later recognized that “we lucked out” – barely.

A closer look at what took place adds grim overtones to these judgments, with reverberations to the present moment. [Continue reading…]

Why the U.S. used nuclear weapons against Japan for political, not military reasons

Washington’s Blog: Like all Americans, I was taught that the U.S. dropped nuclear bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in order to end WWII and save both American and Japanese lives.

But most of the top American military officials at the time said otherwise.

The U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey group, assigned by President Truman to study the air attacks on Japan, produced a report in July of 1946 that concluded (52-56):

Based on a detailed investigation of all the facts and supported by the testimony of the surviving Japanese leaders involved, it is the Survey’s opinion that certainly prior to 31 December 1945 and in all probability prior to 1 November 1945, Japan would have surrendered even if the atomic bombs had not been dropped, even if Russia had not entered the war, and even if no invasion had been planned or contemplated.

General (and later president) Dwight Eisenhower – then Supreme Commander of all Allied Forces, and the officer who created most of America’s WWII military plans for Europe and Japan – said:

The Japanese were ready to surrender and it wasn’t necessary to hit them with that awful thing.

Newsweek, 11/11/63, Ike on Ike

Eisenhower also noted (pg. 380):

In [July] 1945… Secretary of War Stimson, visiting my headquarters in Germany, informed me that our government was preparing to drop an atomic bomb on Japan. I was one of those who felt that there were a number of cogent reasons to question the wisdom of such an act. …the Secretary, upon giving me the news of the successful bomb test in New Mexico, and of the plan for using it, asked for my reaction, apparently expecting a vigorous assent.

During his recitation of the relevant facts, I had been conscious of a feeling of depression and so I voiced to him my grave misgivings, first on the basis of my belief that Japan was already defeated and that dropping the bomb was completely unnecessary, and secondly because I thought that our country should avoid shocking world opinion by the use of a weapon whose employment was, I thought, no longer mandatory as a measure to save American lives. It was my belief that Japan was, at that very moment, seeking some way to surrender with a minimum loss of ‘face’. The Secretary was deeply perturbed by my attitude….

Admiral William Leahy – the highest ranking member of the U.S. military from 1942 until retiring in 1949, who was the first de facto Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and who was at the center of all major American military decisions in World War II – wrote (pg. 441):

It is my opinion that the use of this barbarous weapon at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was of no material assistance in our war against Japan. The Japanese were already defeated and ready to surrender because of the effective sea blockade and the successful bombing with conventional weapons.

The lethal possibilities of atomic warfare in the future are frightening. My own feeling was that in being the first to use it, we had adopted an ethical standard common to the barbarians of the Dark Ages. I was not taught to make war in that fashion, and wars cannot be won by destroying women and children.

Video: Why is Japan restarting its nuclear reactors?

Nuclear weapons are not instruments of peace

Richard Falk writes: A few days ago I was a participant in a well-attended academic panel on ‘the decline of violence and warfare’ at the International Studies Association’s Annual Meeting held this year in San Diego, California. The two-part panel featured appraisal of the common argument of two prominent recent publications: Steven Pinker’s best-selling The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined and Joshua Goldstein’s well-researched, informative, and provocative Winning the War on War: The Decline of Armed Conflict Worldwide. Both books are disposed to rely upon quantitative data to back up their optimistic assessments of international and domestic political behavior, which, if persuasive, offer humanity important reasons to be hopeful about the future. Much of their argument depends on an acceptance of their interpretation of battlefield deaths worldwide, which according to their assessments have declined dramatically in recent decades. But do battlefield deaths tell the whole story, or even the real story, about the role and dangers of political violence and war in our collective lives?

My role was to be a member of the Goldstein half of the panel. Although I had never previously met Joshua Goldstein I was familiar with his work and reputation as a well-regarded scholar in the field of international relations. To offer my response in the few minutes available to me I relied on a metaphor that drew a distinction between a ‘picture’ and its ‘frame.’ I found the picture of war and warfare presented by Goldstein as both persuasive and illuminating, conveying in authoritative detail information about the good work being doing by UN peacekeeping forces in a variety of conflict settings around the world, as well as a careful crediting of peace movements with a variety of contributions to conflict resolution and war avoidance. Perhaps, the most enduringly valuable part of the book is its critical debunking of prevalent myths about the supposedly rising proportion of civilian casualties in recent wars and inflated reports of casualties and sexual violence in the Congo Wars of 1998-2003. These distortions, corrected by Goldstein, have led to a false public perception that wars and warfare are growing more indiscriminate and brutal in recent years, while the most reliable evidence points in the opposite direction.

Goldstein is convincing in correcting such common mistakes about political violence and war in the contemporary world, but less so when it comes to the frame and framing of this picture that is conveyed by his title ‘winning the war on war’ and the arguments to this effect that is the centerpiece of his book, and accounts for the interest that it is arousing. For one thing the quantitative measures relied upon do not come to terms with the heightened qualitative risks of catastrophic warfare or the continued willingness of leading societies to anchor their security on credible threats to annihilate tens of millions of innocent persons, which if taking the form of a moderate scale nuclear exchange (less than 1 percent of the world’s stockpile of weapons) is likely to cause, according to reliable scientific analysis, what has been called ‘a nuclear famine’ resulting in a sharp drop in agricultural output that could last as long as ten years and could be brought about by the release of dense clouds of smoke blocking incoming sunlight.

Also on the panel were such influential international relations scholars as John Mearsheimer who shared with me the view that the evidence in Goldstein’s book did not establish that, as Mearsheimer put it, ‘war had been burned out of the system,’ or that even such a trend meaningfully could be inferred from recent experience. Mearsheimer widely known for his powerful realist critique of the Israeli Lobby (in collaboration with Stephen Walt) did make the important point that the United States suffers from ‘an addiction to war.’ Mearsheimer did not seem responsive to my insistence on the panel that part of this American addiction to war arose from the role being played by entrenched domestic militarism, a byproduct of the permanent war economy that disposed policy makers and politicians in Washington to treat most security issues as worthy of resolution only by considering the options offered by thinking within militarist box of violence and sanctions, a viewpoint utterly resistant to learning from past militarist failures (as in Vietnam, Iraq, Afghanistan, and now Iran). In my view the war addiction is real, but can only be treated significantly if understood to be a consequence of this blinkering of policy choice by a militarized bureaucracy in nation’s capital that is daily reinforced by a compliant media and a misguided hard power realist worldview sustained by high paid private sector lobbyists and the lure of corporate profits, and continuously rationalized by well funded subsidized think tanks such as The Hoover Institution, The Heritage Foundation, and The American Enterprise Institute. Dwight Eisenhower in his presidential farewell speech famously drew attention to the problem that has grown far worse through the years when he warned the country about ‘the military-industrial complex’ back in 1961.

What to me was most shocking about the panel was not its overstated claims that political violence was declining and war on the brink of disappearing, but the unqualified endorsement of nuclear weapons as deserving credit for keeping the peace during Cold War and beyond. Nuclear weapons were portrayed as if generally positive contributors to establishing a peaceful and just world, provided only that they do not fall into unwanted hands (which means ‘adversaries of the West,’ or more colorfully phrased by George W. Bush as ‘the axis of evil’) as a result of proliferation. In this sense, although not made explicit in the conversation, Obama’s vision of a world without nuclear weapons set forth at Prague on April 5, 2009 seems irresponsible from the perspective of achieving a less war-prone world. I had been previously aware of Mearsheimer’s support for this position in his hyper-realist account of how World War III was avoided in the period between 1945-1989, but I was not prepared for Goldstein and the well regarded peace researcher, Andrew Mack, blandly to endorse such a conclusion without taking note of the drawbacks of such ‘a nuclear peace.’ [Continue reading…]

Don’t fear a nuclear arms race in the Middle East

Steven Cook writes: On March 21, Haaretz correspondent Ari Shavit wrote a powerful op-ed in the New York Times that began with this stark and stunning claim: “An Iranian atom bomb will force Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Egypt to acquire their own atom bombs.” Indeed, it has become axiomatic among Middle East watchers, nonproliferation experts, Israel’s national security establishment, and a wide array of U.S. government officials that Iranian proliferation will lead to a nuclear arms race in the Middle East. President Barack Obama himself, in a speech to the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC) last month, said that if Iran went nuclear, it was “almost certain that others in the region would feel compelled to get their own nuclear weapon.”

Multiple nuclear powers on a hair trigger in the Middle East — the most volatile region on earth, and one that is undergoing massive political change — is a nightmare scenario for U.S. and other security planners, who have never before confronted a challenge of such magnitude. But thankfully, all the dire warnings about uncontrolled proliferation are — if not exactly science fiction — further from reality than Shavit and Obama indicate. There are very good reasons for the international community to meet the challenge that Iran represents, but Middle Eastern nuclear dominoes are not one of them.

Theorists of international politics, when pondering the decision-making process of states confronted by nuclear-armed neighbors, have long raised the fears of asymmetric power relations and potential for nuclear blackmail to explain why these states would be forced to proliferate themselves.

This logic was undoubtedly at work when Pakistan embarked on a nuclear program in 1972 to match India’s nuclear development program. Yet for all its tribulations, the present-day Middle East is not the tinderbox that South Asia was in the middle of the 20th century. Pakistan’s perception of the threat posed by India — a state with which it has fought four wars since 1947 — is far more acute than how either Egypt or Turkey perceive the Iranian challenge. And while Iran is closer to home for the Saudis, the security situation in the Persian Gulf is not as severe as the one along the 1,800-mile Indo-Pakistani border.

Most important to understanding why the Middle East will not be a zone of unrestrained proliferation is the significant difference between desiring nukes and the actual capacity to acquire them.

On nuclear programs and nuclear weapons programs

Ali Gharib reports: A consensus seems to be developing on Iran’s nuclear program among those hired by major news organizations to keep an eye on their own reporting. Much of the discussion so far has focused on the latest International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) report on Iran’s nuclear program, the most comprehensive publicly-available evidence on the issue. In the document, the IAEA expressed “serious concerns regarding possible military dimensions to Iran’s nuclear programme.” As a White House official said at the time, the IAEA report neither indicated that Iran has a nuclear weapons program nor that Tehran has made a decision to build a bomb.

A spate of ombudsmen and public editors of major news organizations have come out and bolstered the more accurate reading of the IAEA report — one that raises worries but does not conclude that Iran has a nuclear weapons program. First Washington Post ombud Patrick Pexton said so, urging extra caution because overstating evidence about the program can “play into the hands of those who are seeking further confrontation with Iran.” He was followed by New York Times public editor Arthur Brisbane, who wrote that hewing closely to available facts matters “because the Iranian program has emerged as a possible casus belli.” Now, they’re both being joined by Edward Schumacher-Matos, National Public Radio’s ombudsman, and Public Broadcasting System (PBS) ombudsman Michael Getler.

The Organization of News Ombudsman declares in its mission statement: “The ombudsman refrains from engaging in any activity that could create a conflict of interest.” It also says: “The ombudsman is an independent officer acting in the best interests of news consumers.”

If that was really true then news ombudsmen would neither be appointed by nor paid by the news organizations whose output they monitor. In reality, their function is more a kind of refined public relations — they simply provide newspaper editors, journalists, and the companies inside which they operate, an additional layer of protection.

If NPR and others now studiously try to avoid blurring the distinction between Iran’s nuclear program and a nuclear weapons program whose existence has yet to be established, the most likely effect of doing so will be to provide these news organizations with an extra piece of cover in the event that the media once again comes under scrutiny for the role it might have played in starting a war.

The semantic distinction between “nuclear program” and “nuclear weapons program” is significant, but since these terms have already frequently been used as interchangeable and since in wording they are so similar, it is debatable how much will be gained at this point if some journalists diligently avoid substituting one for the other. Too many news consumers will fail to notice the difference and when hearing “nuclear program” will still think “nuclear weapons program” — the former sounds too much like an abbreviation of the latter.

A more neutral and less ambiguous alternative to “nuclear program” would be “nuclear activities.”

Preventing a nuclear Iran, peacefully

Shibley Telhami and Steven Kull write: The debate over how to handle Iran’s nuclear program is notable for its gloom and doom. Many people assume that Israel must choose between letting Iran develop nuclear weapons or attacking before it gets the bomb. But this is a false choice. There is a third option: working toward a nuclear weapons-free zone in the Middle East. And it is more feasible than most assume.

Attacking Iran might set its nuclear program back a few years, but it will most likely encourage Iran to aggressively seek — and probably develop — nuclear weapons. Slowing Iran down has some value, but the costs are high and the risks even greater. Iran would almost certainly retaliate, leading to all-out war at a time when Israel is still at odds with various Arab countries, and its relations with Turkey are tense.

Many hawks who argue for war believe that Iran poses an “existential threat” to Israel. They assume Iran is insensitive to the logic of nuclear deterrence and would be prepared to use nuclear weapons without fear of the consequences (which could include killing millions of Palestinians and the loss of millions of Iranian civilians from an inevitable Israeli retaliation). And even if Israel strikes, Iran is still likely to acquire nuclear weapons eventually and would then be even more inclined to use them.

Despite all the talk of an “existential threat,” less than half of Israelis support a strike on Iran. According to our November poll, carried out in cooperation with the Dahaf Institute in Israel, only 43 percent of Israeli Jews support a military strike on Iran — even though 90 percent of them think that Iran will eventually acquire nuclear weapons.

Most important, when asked whether it would be better for both Israel and Iran to have the bomb, or for neither to have it, 65 percent of Israeli Jews said neither. And a remarkable 64 percent favored the idea of a nuclear-free zone, even when it was explained that this would mean Israel giving up its nuclear weapons.

The Israeli public also seems willing to move away from a secretive nuclear policy toward greater openness about Israel’s nuclear facilities. Sixty percent of respondents favored “a system of full international inspections” of all nuclear facilities, including Israel’s and Iran’s, as a step toward regional disarmament.

If Israel’s nuclear program were to become part of the equation, it would be a game-changer. Iran has until now effectively accused the West of employing a double standard because it does not demand Israeli disarmament, earning it many fans across the Arab world.

And a nuclear-free zone may be hard for Iran to refuse. Iranian diplomats have said they would be open to an intrusive role for the United Nations if it accepted Iran’s right to enrich uranium for energy production — not to the higher levels necessary for weapons. And a 2007 poll by the Program on International Policy Attitudes found that the Iranian people would favor such a deal.

We cannot take what Iranian officials say at face value, but an international push for a nuclear-free Middle East would publicly test them. And most Arab leaders would rather not start down the nuclear path — a real risk if Iran gets the bomb — and have therefore welcomed the proposal of a nuclear-free zone.

Nuclear scientists are not terrorists

In an op-ed for the New Scientist, Debora MacKenzie writes: Attempts to derail a country’s nuclear programme by killing its scientists “are products of desperation”, says [William] Tobey [of the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at Harvard University] – citing a US effort to kill legendary physicist Werner Heisenberg during the second world war, abandoned at the last minute only when the would-be assassin decided Heisenberg was not involved in a Nazi nuclear effort after all.

“Nuclear scientists are not terrorists,” says Tobey in the BAS this week. Killing them at best delays bomb development, by removing key people and perhaps deterring young scientists from careers in nuclear science. But it will not stop bomb development.

These slim advantages are far outweighed, Tobey says, by the downsides: possible retaliation, reduced chances for diplomacy, tighter security around nuclear installations and a pretext for Iran to hamper IAEA monitoring.

Iran has already accused the IAEA of abetting the assassinations by publicising confidential Iranian lists of key nuclear scientists and engineers.

The IAEA needs such information, as talks with nuclear personnel are considered essential for verifying safeguards against diverting uranium to bombs, says Tobey. Making this process harder only makes sense if the people behind the assassinations think it is too late for safeguards and that slowing bomb R&D by killing scientists is therefore more expedient.

The Israeli columnist Ron Ben-Yishai writes: The most curious question in the face of these incidents is why Iran, which does not shy away from threatening the world with closure of the Hormuz Straits, has failed to retaliate for the painful blows to its nuclear and missile program? After all, the Revolutionary Guards have a special arm, Quds, whose aim (among others) is to carry out terror attacks and secret assassinations against enemies of the regime overseas.

Moreover, if the Iranians do not wish to directly target Western or Israeli interests, they can prompt their agents, that is, Hezbollah, Islamic Jihad and other groups, to do the job. In the past, Iran did not shy away from carrying out terror attacks in Europe (in Paris and Berlin) and in South America (in Buenos Aires,) so why is it showing restraint now?

The reason is apparently Iran’s fear of Western retaliation. Any terror attack against Israel or another Western target – whether it is carried out directly by the Quds force or by Hezbollah – may prompt a Western response. Under such circumstances, Israel or a Western coalition (or both) will have an excellent pretext to strike and destroy Iran’s nuclear and missile sites.

This sounds like a confirmation that Israel is indeed wanting to provoke Iran in order to start a war.

But here’s the paradox: if Iran is intent on developing nuclear weapons then it has ever incentive to continue keeping its powder dry. Why should it jeopardize its nuclear program by succumbing to provocation?

On the other hand if Israel’s covert war does indeed succeed in triggering a full-scale war, this may be an indication that Iran never intended to go further than develop a nuclear break-out capacity.

At the same time, the idea that Iran can only strike back through some form of violence, ignores the economic and psychological levers that it can pull much more easily.

The question may not be how much provocation Iran can withstand but rather how high can the price for oil rise before the global economy buckles?

United States condemns latest murder of an Iranian nuclear scientist

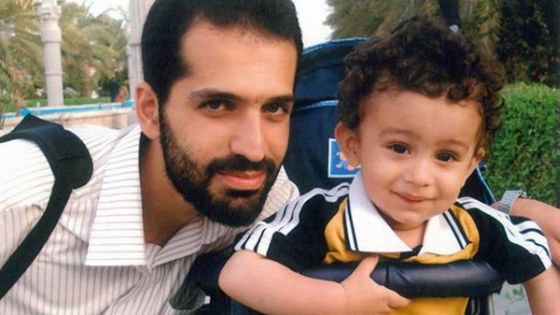

Mostafa Ahmadi Roshan with his son. Roshan is the fifth Iranian nuclear scientist whose murder is being linked to Israel.

The New York Times reports: As arguments flare in Israel and the United States about a possible military strike to set back Iran’s nuclear program, an accelerating covert campaign of assassinations, bombings, cyberattacks and defections appears intended to make that debate irrelevant, according to current and former American officials and specialists on Iran.

The campaign, which experts believe is being carried out mainly by Israel, apparently claimed its latest victim on Wednesday when a bomb killed a 32-year-old nuclear scientist in Tehran’s morning rush hour.

The scientist, Mostafa Ahmadi Roshan, was a department supervisor at the Natanz uranium enrichment plant, a participant in what Western leaders believe is Iran’s halting but determined progress toward a nuclear weapon. He was at least the fifth scientist with nuclear connections to be killed since 2007; a sixth scientist, Fereydoon Abbasi, survived a 2010 attack and was put in charge of Iran’s Atomic Energy Organization.

Iranian officials immediately blamed both Israel and the United States for the latest death, which came less than two months after a suspicious explosion at an Iranian missile base that killed a top general and 16 other people. While American officials deny a role in lethal activities, the United States is believed to engage in other covert efforts against the Iranian nuclear program.

The assassination drew an unusually strong condemnation from the White House and the State Department, which disavowed any American complicity. The statements by the United States appeared to reflect serious concern about the growing number of lethal attacks, which some experts believe could backfire by undercutting future negotiations and prompting Iran to redouble what the West suspects is a quest for a nuclear capacity.

“The United States had absolutely nothing to do with this,” said Tommy Vietor, a spokesman for the National Security Council. Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton appeared to expand the denial beyond Wednesday’s killing, “categorically” denying “any United States involvement in any kind of act of violence inside Iran.”

Assassination in Tehran: An act of war?

M.J. Rosenberg writes: I rarely learn anything meaningful from reading The Atlantic‘s Jeffrey Goldberg. In my opinion, his tight relationship with the Israeli government and its lobby here greatly influences his take on both foreign and domestic events. Although he occasionally deviates from the Israeli line, he not only appears very uncomfortable doing so, he tends to correct course fairly rapidly.

Nonetheless, in a Goldberg column about Iran this week, there was one paragraph that was dead-on and which he will have a hard time taking back (should he be so inclined).

Writing about a piece in the current edition of Foreign Affairs that endorses bombing Iran as a neat and cost-free way to address its nuclear program, Goldberg explains why he thinks the author, Council on Foreign Relations fellow Matthew Kroenig, is wrong. Goldberg says he now believes:

…that advocates of an attack on Iran today would be exchanging a theoretical nightmare — an Iran with nukes — for an actual nightmare, a potentially out-of-control conventional war raging across the Middle East that could cost the lives of thousands Iranians, Israelis, Gulf Arabs and even American servicemen.

Think about that for a minute. Uber-hawk Jeffrey Goldberg is saying that the threat posed by Iran is a “theoretical nightmare” while a war ostensibly to neutralize that threat would present an “actual nightmare.”

No critic of U.S. policy toward Iran could say it better or would say it differently. And why would we?

According to the International Atomic Energy Agency, Iran has not yet made the decision to go nuclear. Speaking to CBS’ Face the Nation last Sunday, Defense Secretary Leon Panetta made the same point. Iran is not working on the bomb.

We do know, as Goldberg says, that a “potentially out-of-control conventional war raging across the Middle East” could “cost the lives of thousands of Iranians, Israelis, Gulf Arabs and even American servicemen.”

And that makes the decision against war a no-brainer. As Goldberg puts it:

Now that sanctions seem to be biting — in other words, now that Iran’s leaders understand the President’s seriousness on the issue — the Iranians just might be willing to pay more attention to proposals about an alternative course.

That alternative course would be an attempt “to try one more time to reach out to the Iranian leadership in order to avoid a military confrontation over Tehran’s nuclear program.”

In short, dialogue.

The United States, to this day, has never attempted a true dialogue with the Tehran. Even under President Obama, all we have done is issue demands about its nuclear program and offer to meet to discuss precisely how they comply with those demands.

That is not dialogue and it’s not negotiation; it’s an ultimatum.

Doomsday Clock ticks one minute closer to midnight

The Guardian reports: The world tiptoed closer to the apocalypse on Tuesday as scientists moved the Doomsday Clock one minute closer to the zero hour.

The symbolic clock now stands at five minutes to midnight, the scientists said, because of a collective failure to stop the spread of nuclear weapons, act on climate change, or find safe and sustainable sources of energy – as exemplified by the Fukushima nuclear disaster.

The rare bright points the scientists noted were the Arab spring and movement in Russia for greater democracy.

The clock, maintained by the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, has been gauging our proximity to global disaster since 1947, using the potent image of a clock counting down the minutes to destruction. Until Tuesday afternoon, the clock had been set at six minutes to midnight.

“It is five minutes to midnight,” the scientists said. “Two years ago it appeared that world leaders might address the truly global threats we face. In many cases, that trend has not continued or been reversed.”

Israel prepares for nuclear-armed Iran

The Times reports: Israel has begun thinking the unthinkable: that it will have to deal with a nuclear-armed Iran within a year.

In documents seen by The Times, Israeli officials have begun preparing scenarios for the day after a nuclear weapons test.

The move is a tacit recognition that Israel is backing away from its long-held position that it would do everything in its power – including mounting a military strike – to stop Iran acquiring nuclear capabilities.

Details of the war game, which was enacted by former ambassadors, intelligence officials and ex-military chiefs, emerged as the United Nations’ nuclear watchdog confirmed yesterday that Iran has begun producing enriched uranium in an underground bunker designed to withstand airstrikes.

The International Atomic Energy Agency said that it was monitoring the work at the Fordow facility, which is concealed in a mountain near the holy city of Qom.

The simulation exercise was conducted in Tel Aviv last week by the Institute for National Security Studies (INSS), a think-tank. Its conclusions suggest that a nuclear test would radically shift the whole power balance of the Middle East.

Iran starts uranium enrichment at Fordo mountain facility, Kayhan reports

Bloomberg reports: Iran has started to enrich uranium at its Fordo production facility, the official Kayhan newspaper reported without saying where it got the information.

Iran will soon have a ceremony to open the site officially, the newspaper reported, citing the head of the Iranian Atomic Energy Organization, Fereydoun Abbasi. The Iranian nuclear chief was cited yesterday by Mehr News as saying that the underground facility “will start operating in the near future.”

The existence of the Fordo plant, built into the side of a mountain near the Muslim holy city of Qom, south of Tehran, was disclosed in September 2009, heightening concern among the U.S. and its allies who say Iran’s activities may be a cover for the development of atomic weapons. The Persian Gulf country has rejected the allegation, saying it needs nuclear technology to secure energy for its growing population.

The Associated Press reports: Defense Secretary Leon Panetta says Iran is laying the groundwork for making nuclear weapons someday, but is not yet building a bomb and called for continued diplomatic and economic pressure to persuade Tehran not to take that step.

As he has previously, Panetta cautioned against a unilateral strike by Israel against Iran’s nuclear facilities, saying the action could trigger Iranian retaliation against U.S. forces in the region.

“We have common cause here” with Israel, he said. “And the better approach is for us to work together.”

Panetta’s remarks on CBS’ Face the Nation, which were taped Friday and aired Sunday, reflect the long-held view of the Obama administration that Iran is not yet committed to building a nuclear arsenal, only to creating the industrial and scientific capacity to allow one if its leaders to decide to take that final step.