U.S. security talks with Iraq in trouble in Baghdad and D.C.

A proposed U.S.-Iraqi security agreement that would set the conditions for a defense alliance and long-term U.S. troop presence appears increasingly in trouble, facing growing resistance from the Iraqi government, bipartisan opposition in Congress and strong questioning from Democratic presidential candidate Barack Obama.

President Bush is trying to finish the agreement before he leaves office, and senior U.S. officials insist publicly that the negotiations can be completed by a July 31 target date. The U.S. is apparently scaling back some of its demands, including backing off one that particularly incenses Iraqis, blanket immunity for private security contractors.

But meeting the July 31 deadline seems increasing doubtful, and in Baghdad and Washington there is growing speculation that a United Nations mandate for U.S.-led military operations in Iraq may have to be renewed after it expires at the end of 2008.

President Bush regrets his legacy as man who wanted war

President Bush has admitted to The Times that his gun-slinging rhetoric made the world believe that he was a “guy really anxious for war” in Iraq. He said that his aim now was to leave his successor a legacy of international diplomacy for tackling Iran.

In an exclusive interview, he expressed regret at the bitter divisions over the war and said that he was troubled about how his country had been misunderstood. “I think that in retrospect I could have used a different tone, a different rhetoric.”

Editor’s Comment — In the twilight of his presidency, George Bush has a focus that’s easy to miss. At a point when he has virtually become a pariah, it hardly seems worth paying attention to anything he says. Even so, what he said to The Times echoes what he recently said to The Jerusalem Post. A mid-May editorial said: “The president told The Jerusalem Post yesterday that before leaving office he wants a structure in place for dealing with Iran.” The Times reiterates: “He said that his aim now was to leave his successor a legacy of international diplomacy for tackling Iran… The President was keen to bind his successor into a continued military presence in Afghanistan and Iraq.”

All of which points to the central importance, in Bush’s mind, of securing signatures on long-term defense agreements with Iraq – agreements that the administration refuses to acknowledge as legal treaties, so that it can circumvent the need for Congressional approval. This — not plans to attack Iran — seems to be what’s on Bush’s mind as he contemplates his legacy.

The neonconservative fantasist, Daniel Pipes, has suggested that “should the Democratic nominee win in November, President Bush will do something. And should it be Mr McCain that wins, he’ll punt, and let McCain decide what to do.”

The idea that while a transition between administrations is already in process, Bush is going to start a last minute war, is frankly absurd. What is far from fanciful is what Bush is actually saying – that he is keen to bind his successor.

If there’s a trend that has run unbroken throughout George Bush’s two terms in office, it is his consistent ability to empower his adversaries. The Maliki government is only nominally a US ally, and at this juncture it seems well-placed to take advantage of the pressure being applied by Washington. Time is on Baghdad’s side. Indeed, if Maliki can hang on long enough to welcome the arrival of an Obama administration, he might also be able to step into a unique strategic position: as a mediator between Washington and Tehran.

Relax, liberals. You’ve already won

Now that Hillary Clinton has conceded the Democratic nomination to Barack Obama, the primaries are over and the general election campaign for the White House has begun. On the Republican side, however, the general election campaign began months ago — and presumptive nominee John McCain has spent much of that time tacking toward the center. He praised multilateralism in a March 26 speech in Los Angeles and in general is trying to appear more like an Eisenhower Republican than a Reagan Republican. True, every four years all major-party presidential candidates race toward the center. But in the last decade, even during the seven-plus years of the Bush presidency, the center of American politics has moved considerably to the left. Whether Obama or McCain wins the White House, liberalism has already won the national debate about the future of the country.

For 40 years, the radical right tried to destroy the domestic and international order that American liberals created in the central decades of the 20th century. The people who are known today as “conservatives” are better described as “counterrevolutionaries.” The goal of Barry Goldwater and the intellectuals clustered around William F. Buckley Jr.’s National Review was not a slightly more conservative version of the New Deal or the U.N. system. They were reactionary radicals who dreamed of a counterrevolution. They didn’t just want to stop the clock. They wanted to turn it back.

Three great accomplishments defined midcentury American liberalism: liberal internationalism, middle-class entitlements like Social Security and Medicare, and liberal individualism in civil rights and the culture at large. For four decades, from 1968 to 2008, the counterrevolutionaries of the right waged war against the New Deal, liberal internationalism, and moral and cultural liberalism. They sought to abolish middle-class entitlements like Social Security and Medicare, to replace treaties and collective security with scorn for international law and U.S. global hegemony, and to reverse the trends toward individualism, secularism and pluralism in American culture.

These objects of contempt are now our best chance of feeding the world

I suggest you sit down before you read this. Robert Mugabe is right. At last week’s global food summit he was the only leader to speak of “the importance of land in agricultural production and food security”. Countries should follow Zimbabwe’s lead, he said, in democratising ownership.

Of course the old bastard has done just the opposite. He has evicted his opponents and given land to his supporters. He has failed to support the new settlements with credit or expertise, with the result that farming in Zimbabwe has collapsed. The country was in desperate need of land reform when Mugabe became president. It remains in desperate need of land reform today.

But he is right in theory. Though the rich world’s governments won’t hear it, the issue of whether or not the world will be fed is partly a function of ownership. This reflects an unexpected discovery. It was first made in 1962 by the Nobel economist Amartya Sen, and has since been confirmed by dozens of studies. There is an inverse relationship between the size of farms and the amount of crops they produce per hectare. The smaller they are, the greater the yield.

One man’s online journey through Bush’s alphabet soup

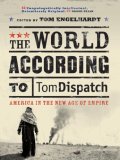

T omDispatch is — as I often write inquisitive readers — the sideline that ate my life. Being in my late fifties and remarkably ignorant of the Internet world when it began, I brought some older print habits online with me. These included a liking for the well-made, well-edited essay, an aversion to the endless yak and insult that seemed to fill whole realms of cyberspace, and a willingness to go against, or beyond, every byte-sized truth of the online world where, it was believed, brevity was all and attention spans virtually nonexistent. TomDispatch pieces invariably ran long. They were, after all, meant to reframe a familiar, if shook-up, world that was being presented in a particularly limited way by the mainstream media.

omDispatch is — as I often write inquisitive readers — the sideline that ate my life. Being in my late fifties and remarkably ignorant of the Internet world when it began, I brought some older print habits online with me. These included a liking for the well-made, well-edited essay, an aversion to the endless yak and insult that seemed to fill whole realms of cyberspace, and a willingness to go against, or beyond, every byte-sized truth of the online world where, it was believed, brevity was all and attention spans virtually nonexistent. TomDispatch pieces invariably ran long. They were, after all, meant to reframe a familiar, if shook-up, world that was being presented in a particularly limited way by the mainstream media.

Finding myself on a mad, unipolar imperial planet, I simply took the plunge into an alphabet soup of mayhem and chaos. Let me try, now, to offer you my shorthand version of the world according to TomDispatch.

In Iran, things can always get worse

On May 28, Ali Larijani, former nuclear negotiator and close confidant of Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamene’i, won the position of speaker of the Majlis, Iran’s parliament. Larijani is a member of the mainline conservative faction in Iran — which is different from the more radical faction led by President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. (Iranian political observers have aptly borrowed the American term “neoconservative” to refer to the Ahmadinejad faction.)

Larijani’s rise was the first of a series of political changes in Iran. At about this time next year, Iran will hold a presidential election. Its outcome could depend, in part, on the outcome of the 2008 elections here in the United States. Given the serious disputes between the two countries and the prospect of another war in the Middle East, Americans — and American presidential candidates — should take a moment to think about how our election could influence Iran’s.