One of the most pernicious effects of the Bush era was that the neocons succeeded in turning so many progressives into realists.

Before Bush, “the national interest” was correctly viewed as the abiding concern of insular conservatives. It meant that Americans should be concerned with the rest of the world only in as much as anything going on out there could impact American interests — above all this meant American economic interests.

Now we have liberals and progressives who seem to have somehow discovered their William F Buckley Jr within — their preeminent concern has become the national interest. It’s all well and good to go and intervene in Libya, but does this serve United States’ national interests?

If realism was meant to be the antidote to neoconservatism, it’s definitely been overrated.

A neoconservative looks into a mirror and thinks he’s looking at the future. A realist looks into the future and can only see the past.

The neocon’s preeminent thinker, Robert Kagan, gave Obama this rave review after his speech on Libya last night:

With his speech tonight, President Obama placed himself in a great tradition of American presidents who have understood America’s special role in the world. He thoroughly rejected the so-called realist approach, extolled American exceptionalism, spoke of universal values and insisted that American power should be used, when appropriate, on behalf of those values. I was particularly pleased to see him place Libya in the context of the Arab Spring. This is the part of the equation that the self-described realists have missed. While in isolation acting to defend the people of Libya against Moammar Gaddafi might not seem imperative, it is in the broader context of the revolutionary moment in the Middle East that U.S. actions take on greater significance. Tonight the president began to place the United States on the right side of the unfolding history in the region.

The president also deserves credit for showing, once again, how bold and effective U.S. leadership can pave the way for multilateral efforts. He has been right to insist that others take their fair share of the burden, but he has also made clear that American leadership was essential, even indispensable.

This was a Kennedy-esque speech.

Meanwhile, Fred Kaplan at Slate was equally enthusiastic — but for different reasons:

President Barack Obama’s speech on Libya Monday night was about as shrewd and sensible as any such address could have been.

Some of his critics hoped he would outline a grand strategy on the use of force for humanitarian principles. Some demanded that he go so far as to declare what actions he would or would not take, and why, in Syria, Bahrain, and other nations where authoritarian rulers fire bullets at their own people. Still others urged him to spell out when the air war will stop, how we’ll exit, who will help the Libyan people rebuild their country after Qaddafi goes, and what we’ll do if he doesn’t go.

These are all interesting matters, but they evade the two main questions, which Obama confronted straight on. First, under the circumstances, did the United States really have any choice but to intervene militarily? Second, for all the initial hesitations and continuing misunderstandings, would the actions urged by his critics (on the left and right) have led to better results? For that matter, have any presidents of the last couple of decades dealt with similar crises more wisely?

The answers to all those questions: No.

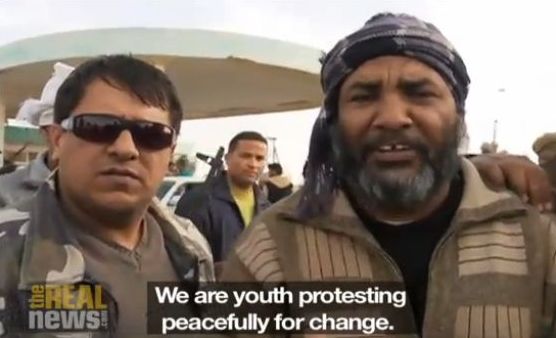

Curiously, Obama left out any mention of the rebel fighters. They could be forgiven for now wondering whether this is mostly because Washington is reluctant to place itself alongside images of young (and not so young) men wearing keffiyehs, carrying AK-47s and RPGs.

The closest Obama came to clearly delineating the relationship between the US intervention and the Libyan revolution was here:

… America has an important strategic interest in preventing Gaddafi from overrunning those who oppose him. A massacre would have driven thousands of additional refugees across Libya’s borders, putting enormous strains on the peaceful – yet fragile – transitions in Egypt and Tunisia. The democratic impulses that are dawning across the region would be eclipsed by the darkest form of dictatorship, as repressive leaders concluded that violence is the best strategy to cling to power. The writ of the UN Security Council would have been shown to be little more than empty words, crippling its future credibility to uphold global peace and security. So while I will never minimize the costs involved in military action, I am convinced that a failure to act in Libya would have carried a far greater price for America.

Now, just as there are those who have argued against intervention in Libya, there are others who have suggested that we broaden our military mission beyond the task of protecting the Libyan people, and do whatever it takes to bring down Gaddafi and usher in a new government.

Of course, there is no question that Libya – and the world – will be better off with Gaddafi out of power. I, along with many other world leaders, have embraced that goal, and will actively pursue it through non-military means. But broadening our military mission to include regime change would be a mistake.

The US and its allies have taken sides in Libya, but holding back from making regime change the coalition’s military goal shouldn’t be seen as merely a PR gambit designed to protect the mission’s chosen branding: “humanitarian intervention”.

The rebels now have a fighting chance of winning, but the revolution itself cannot be completely outsourced to foreign powers.

As for the idea that the US has a strategic interest in the success of the wider revolution, I’m not about to claim that having previously displayed such a lack of interest in the rights of ordinary people across the region, the US has now been reborn as the indispensable champion of democracy that the neocons claim. But the emerging democracies across the Arab world will be keenly aware of the role that the US has had in advancing or obstructing this historic trend.

An effort to get on the right side of history has less to do with demonstrating America’s moral character than diminishing the depth of its untrustworthiness in the eyes of those it has long abused.