The Telegraph reports: Born in 1994, the second youngest of four children, Abedi’s parents were Libyan refugees who fled to the UK to escape Gaddafi.

His mother, Samia Tabbal, 50, and father, Ramadan Abedi, a security officer, were both born in Tripoli but appear to have emigrated to London before moving to the Whalley Range area of south Manchester where they had lived for at least a decade.

Abedi went to school locally and then on to Salford University in 2014 where he studied business management before dropping out. His trips to Libya, where it is thought his parents returned in 2011 following Gaddafi’s overthrow, are now subject to scrutiny including links to jihadists.

A group of Gaddafi dissidents, who were members of the outlawed Libyan Islamic Fighting Group (LIFG), lived within close proximity to Abedi in Whalley Range.

Among them was Abd al-Baset Azzouz, a father-of-four from Manchester, who left Britain to run a terrorist network in Libya overseen by Ayman al-Zawahiri, Osama bin Laden’s successor as leader of al-Qaeda.

Azzouz, 48, an expert bomb-maker, was accused of running an al-Qaeda network in eastern Libya. The Telegraph reported in 2014 that Azzouz had 200 to 300 militants under his control and was an expert in bomb-making.

Another member of the Libyan community in Manchester, Salah Aboaoba told Channel 4 news in 2011 that he had been fund raising for LIFG while in the city. Aboaoba had claimed he had raised funds at Didsbury mosque, the same mosque attended by Abedi. The mosque at the time vehemently denied the claim. “This is the first time I’ve heard of the LIFG. I do not know Salah,” a mosque spokesman said at the time.

At the mosque, Mohammed Saeed El-Saeiti, the imam at the Didsbury mosque yesterday branded Abedi an dangerous extremist. “Salman showed me the face of hate after my speech on Isis,” said the imam. “He used to show me the face of hate and I could tell this person does not like me. It’s not a surprise to me.” [Continue reading…]

Category Archives: War in Libya

America’s habit of winning wars then losing the peace

Dominic Tierney writes: In Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya, Washington toppled regimes and then failed to plan for a new government or construct effective local forces — with the net result being over 7,000 dead U.S. soldiers, tens of thousands of injured troops, trillions of dollars expended, untold thousands of civilian fatalities, and three Islamic countries in various states of disorder. We might be able to explain a one-off failure in terms of allies screwing up. But three times in a decade suggests a deeper pattern in the American way of war.

In the American mind, there are good wars: campaigns to overthrow a despot, with the model being World War II. And there are bad wars: nation-building missions to stabilize a foreign country, including peacekeeping and counterinsurgency. For example, the U.S. military has traditionally seen its core mission as fighting conventional wars against foreign dictators, and dismissed stabilization missions as “military operations other than war,” or Mootwa. Back in the 1990s, the chairman of the joint chiefs reportedly said, “Real men don’t do Mootwa.” At the public level, wars against foreign dictators are consistently far more popular than nation-building operations.

The American way of war encourages officials to fixate on removing the bad guys and neglect the post-war stabilization phase. When I researched my book How We Fight, I found that Americans embraced wars for regime change but hated dealing with the messy consequences going back as far as the Civil War and southern reconstruction. [Continue reading…]

The Arab revolutions have been misunderstood or even wilfully mischaracterised by Western leftists

In a review of Burning Country: Syrians in Revolution and War, by Robin Yassin-Kassab and Leila al-Shami, Joe Gill writes: As well as a non-orthodox telling of the conflict from the point of view of the activists and fighters who took part in the revolution, the book also speaks to the confusion and reluctance of western progressives to engage in the reality of Syria. “What’s happening is of immense human, cultural importance, not just for Syria and the Middle East but for the whole world. We do actually live in age of very messy revolutions,” says Yassin-Kassab.

Western suspicion of Islamists of whatever hue colours how the Syrian revolution is perceived, leading to potentially disastrous conclusions as to how the war might be ended. “There are a huge range of Islamists – we don’t at all agree with them, but nevertheless they are there. Some are foreigners and criminals, some of them are Syrians and represent a constituency,” said Yassin-Kassab.

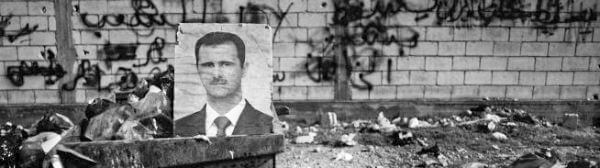

By late 2013, and certainly by 2015, a consensus had emerged in the West, if not in the Gulf and Turkey, that there were no good opposition forces left on the ground who could take the reigns if and when Assad fell.

The Arab revolutions, because they do not conform to a traditional Marxist or anti-colonial narrative of liberation struggles, and in the case of Syria and Libya are ranged against nominally “anti-imperialist” regimes, have also been misunderstood or even wilfully mischaracterised by western leftists, according to al-Shami and Yassin-Kassab. “I actually fail to see the difference between the left and right as a result of all this. You don’t hear anything about [the Syrian revolutionary movement] in western leftist circles. You need to go to the grassroots to what people are really thinking and feeling.” Without this bottom up approach, the author says that outsiders are “open to the first propagandist narrative that comes along.” [Continue reading…]

Libya: To intervene, or not to intervene, that is not the question

The New York Times: Largely overshadowed by the crises in Syria, Iraq and Ukraine, Libya’s unraveling has received comparatively little attention over the past few months. As this oil-rich nation veers toward complete chaos, world leaders would be wise to redouble efforts led by the United Nations to broker a power-sharing deal among warring factions.

A few of the Islamist groups vying for control in Libya have pledged allegiance to the Islamic State and carried out the type of barbaric executions that have galvanized international support for the military campaign against the terrorist group in Iraq and Syria. The growth and radicalization of Islamist groups raise the possibility that large parts of Libya could become a satellite of the Islamic State.

“Libya has the same features of potentially becoming as bad as what we’re seeing in Iraq and Syria,” Bernardino León, the United Nations envoy to Libya, said in an interview. “The difference is that Libya is just a few miles away from Europe.” [Continue reading…]

Jenan Moussa sardonically observes:

What does #Libya teach us? With intervention, you get ISIS. What does #Syria teach us? Without intervention, you get ISIS. #sigh

— Jenan Moussa (@jenanmoussa) February 15, 2015

Now as always, those who reflexively argue against all forms of intervention will maintain the conceit that to do nothing is to do no harm. The unspoken assumption is: if we do nothing, we will suffer no harm. It’s not so much a mind your own business, live and let live, philosophy. More like, live and let die.

But as Richard Haass points out, intervention does not simply involve a binary choice:

real #Libya scandal is not Benghazi but rather decisions to intervene & then walk away. result is 3 failed states http://t.co/LF44DGDOqE

— Richard N. Haass (@RichardHaass) February 15, 2015

When Barack Obama reluctantly led from behind in 2011, joining in the NATO intervention which toppled Gaddafi, his attention was much more keenly focused on domestic politics and an upcoming election, than it was on the fate of Libya. He placed higher value on the intervention ending than on what might follow. That Libyan oil quickly started flowing again looked like a success — from a Western and myopic vantage point.

But even though Libyans understandably did not want to see international powers controlling what essentially amounted to the construction of a new state, it seems like the international community missed an opportunity to use oil revenues as a political tool. If revenues had been paid into a UN-controlled account instead of directly to the National Oil Company, their release to the central bank and government could have been made contingent on a set of political milestones being passed such as disarming the militias.

The Libyan economy is totally dependent on oil and the desire to continue selling oil is the one common interest that unites all political factions. Left to their own devises, each will vie for control of the oil supply and revenues. But the power to determine whether oil is a source of division or unity could rest in the hands of the buyers. The world can manage without Libyan oil but Libya can’t survive without selling oil.

No one — apart from ISIS — has an interest in Libya becoming an irretrievably failed state.

Libya’s descent into chaos: Warring clans and its impact on regional stability

Jamestown Terrorism Monitor: Since the outbreak of the Libyan revolution in 2011 and the collapse of Mu’ammar Qaddafi’s Jamahiriya (Republic of the Masses), Libya has fallen into a process of constant and ever deeper chaos, which has lately reached a new climax. This conflict, however, has its roots in some specific features characterizing Libya as a “nation-state”: while Libya may be a nation-state on paper, it has yet to become a proper and unified national society. Indeed, the very roots of the revolution in Libya lie in the significant structural, regional and territorial imbalances that have characterized Libya since its establishment and the dominance of parochial and narrow interests.

Indeed, regional and political imbalances – the neglected east and south against the stronger and richer west – were key in setting the landscape in which the Libyan revolution took place. Revolts started in Benghazi and moved east to west, with a long military stalemate occurring in Ras Lanuf, historically a sort of informal cultural border dividing Tripolitania and Cyrenaica. Geographically, this was similar to what happened with the 1969 revolution. That revolution was a reaction against the dominance of the east, Benghazi and the royal circle. Among the 12 members of the Revolutionary Command Council, which led the revolution and then acted as the supreme authority in Libya between 1969 and 1975, only four were from the east.

Moreover, another factor explaining the complete collapse of order in post-Qaddafi Libya is the complete lack of any reliable state institution. Despite being the “Republic of the Masses”, Qaddafi’s Jamahiriya was essentially based on his sole, complete personal rule: 42 years under this system left Libya as a sort of institutional desert following the collapse of the regime. The regime overlapped the state and as a result the boundaries, both conceptual and organizational, between the two became soon nonexistent. That explains why, in Libya, the fall of the regime caused the fall of the state, unlike in Tunisia and Egypt where the regimes, not the state, collapsed. However, this lack of institutional capacity must be seen in a longer-term perspective: that was a structural feature of Libya as a nation-state since its foundation. Libya at independence did not have a stable state apparatus and oil and external revenue allowed the rulers to avoid building a bureaucratic state, moving from the rentier patronage of King Idris and the Senussi monarchy to the distributive republic led by Qaddafi. [Continue reading…]

Saddam Hussein’s faithful friend, the King of Clubs, might be the key to saving Iraq

Michael Knights writes: Over the weekend, in what the Telegraph described as “a potential sign of the fraying of the Sunni insurgent alliance that has overrun vast stretches of territory north of Baghdad in less than two weeks,” a deadly firefight broke out west of Kirkuk, Iraq, between members of the Islamic State of Iraq and Al-Sham and a rival insurgent group called Jaysh Rijal al-Tariq al-Naqshbandi, or the Army of the Men of the Naqshbandi. JRTN now represents the main obstacle to ISIS’s creation of an Islamic caliphate spanning Iraq and Syria, and is most likely being led by Saddam Hussein’s old friend Izzat Ibrahim al-Douri, the King of Clubs from the infamous deck of cards of most-wanted Iraqis — that is, if he’s not dead.

Born in 1942, Douri came from Dawr, a town of 35,000 people on the east bank of the Tigris and just 20 miles from Hussein’s birthplace (and burial place) of Al-Awja. Growing up poor, Douri worked for an ice-seller as a boy but quickly turned to violent revolutionary politics in his late teenage years. He worked alongside Hussein, who, being a few years older, was Douri’s mentor. They both served in the intelligence and peasantry offices of the Baath Party and later spent time in jail together after the Baath’s brief seizure of power in 1963. Douri remained as Hussein’s eyes and ears in Iraq while Hussein was abroad for the five years preceding the Baathist return to power in 1968.

Back in power, Douri and Hussein picked up where they left off — as inseparable partners. Douri was rewarded for his loyalty by inheriting Hussein’s prior position, the vice presidency and deputy chairmanship of the Iraqi Revolutionary Command Council. Until Hussein’s capture in 2003, Douri served as his most trusted deputy, always careful not to threaten Hussein’s position. The Douris consistently backed Hussein, and the two families even merged for a time. In a show of loyalty, Douri consented to marry his daughter to Hussein’s eldest son, the infamous sadist Uday. As Iraqi tribal expert Amatzia Baram told me years ago, Douri’s sway with Hussein was so substantial that he could even levy a condition — that the union would not be consummated — and later made a successful petition that his daughter be permitted to divorce Hussein’s homicidal offspring.

But aside from keeping Hussein happy and in charge, Douri also had a personal project, a patronage network that he jealously guarded for himself. The name of that network was the Men of the Naqshbandi. [Continue reading…]

Video: Matthew VanDyke talks about fighting in Libya and filming in Syria

![]() There are probably a lot more people who hold strong opinions about Matthew VanDyke than there are who have bothered spending any time listening to him explain himself.

There are probably a lot more people who hold strong opinions about Matthew VanDyke than there are who have bothered spending any time listening to him explain himself.

Branded variously as an adventurer, war tourist, terrorist, and freedom fighter, one of the curious features of VanDyke’s story is that if he wore a U.S. military uniform and described himself as having fought for what he believes in, he would probably have avoided much of the criticism. Opponents of war are much more comfortable blaming U.S. governments for America’s military misadventures of the last twelve years than holding individual soldiers responsible. VanDyke, on the other hand, is supposedly guilty of some unconscionable form of recklessness for having involved himself, of his own free will, in wars in Libya and Syria.

While VanDyke’s original decision to go to the Middle East emerged out his desire to make adventure films, his knowledge of the region was already much more advanced than the average American reporter who got sent out to cover the war in Iraq.

[In 2002] VanDyke entered Georgetown University’s prestigous Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service in Washington, D.C., where he says he was a bit of an oddity. “There were people who were in the military, in the CIA, working for the State Department,” he explains, “and there I was, riding my skateboard to class.” VanDyke, too, wanted to work for the CIA, explaining that he “was mesmerized by the Hollywood aspect of it, my fictitious image of what the CIA does. Now I know it’s more like a mixture of James Bond and the U.S. Post Office, as one of my friends who works in U.S. intelligence has told me.”

While in the process of applying for a summer internship at the CIA, VanDyke’s problems with authority came to the fore. “I went to my first CIA interview, and that day, after the interview, I went to my first Iraq War protest,” he recalls. “I didn’t really see a conflict at the time. I nailed the interview and I got pretty far through the process.” But his polygraph test kept getting delayed as his anti-war activism grew, and ultimately, he decided against reapplying. “With a concentration in Middle East security studies, they were going to put me on the Iraq War,” he explains, “and I didn’t want to work on a war I didn’t believe in.”

Studying ritual in order to understand politics in Libya

When I was an undergraduate, early on I learned about the value of interdisciplinary studies. Had I been on a conventional academic track, that probably wouldn’t have happened, but I was lucky enough to be in a department that brought together anthropologists, sociologists, philosophers, theologians, and religious studies scholars. In such an environment, the sharp defense of disciplinary turf was not only unwelcome — it simply made no sense.

Even so, universities remain structurally antagonistic to interdisciplinarity, both for intellectual reasons but perhaps more than anything for professional reasons. Anyone who wants to set themselves on a track towards tenure needs to get published and academic journals all fall within and help sustain disciplinary boundaries.

I mention this because when questions are raised such as what’s happening in Libya? or the more loaded, what’s gone wrong in Libya? the range of experts who get called on to respond, tends to be quite limited. There will be regional experts, political scientists, and perhaps economists. But calling on someone with an understanding of the human function of ritual along with the role different forms of ritual may have had in the development of civilization, is not an obvious way of trying to gain insight into events in Benghazi.

Moreover, within discourse that is heavily influenced by secular assumptions about the problematic nature of religion and the irrational roots of extremism, there is a social bias in the West that favors a popular dismissal.

What’s wrong with Libya? Those people are nuts.

Philip Weiss helped popularize the expression Progressive Except on Palestine — an accusation that most frequently gets directed at American liberal Zionists. But over the last two years a new variant which is perhaps even more commonplace has proliferated across the Left which with only slight overstatement could be called Progressive Except on the Middle East.

From this perspective, a suspicion of Muslim men with beards — especially those in Libya and Syria — has become a way through which a Clash of Civilizations narrative is unwittingly being reborn. Add to that the influence of the likes of Richard Dawkins and his cohorts on their mission to “decry supernaturalism in all its forms” and what you end up with is a stifling of curiosity — a lack of any genuine interest in trying to understand why people behave the way they do if you’ve already concluded that their behavior is something to be condemned.

A year ago, the science journal Nature, published an article on human rituals, their role in the growth of community and the emergence of civilization.

The report focuses on a global project one of whose principal aims is to test a theory that rituals come in two basic forms: one that through intense and often traumatic experience can forge tight bonds in small groups and the other that provides social cohesion less intensely but on a larger scale through doctrinal unity.

Last week, the State department designated three branches of Ansar al Shariah — two in Libya and one in Tunisia — as terrorist organizations. The information provided gives no indication about how or if the groups are linked beyond the fact that they share the same name — a name used by separate groups in eight different countries.

There’s reason to suspect that the U.S. government is engaged in its own form of ritualistic behavior much like the Spanish Inquisition busily branding heretics.

Maybe if the Obama administration spent a bit more time talking to anthropologists and archeologists rather than political consultants and security advisers, they would be able to develop a more coherent and constructive policy on Libya. I’m not kidding.

In Nature, Dan Jones writes: By July 2011, when Brian McQuinn made the 18-hour boat trip from Malta to the Libyan port of Misrata, the bloody uprising against Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi had already been under way for five months.

“The whole city was under siege, with Gaddafi forces on all sides,” recalls Canadian-born McQuinn. He was no stranger to such situations, having spent the previous decade working for peace-building organizations in countries including Rwanda and Bosnia. But this time, as a doctoral student in anthropology at the University of Oxford, UK, he was taking the risk for the sake of research. His plan was to make contact with rebel groups and travel with them as they fought, studying how they used ritual to create solidarity and loyalty amid constant violence.

It worked: McQuinn stayed with the rebels for seven months, compiling a strikingly close and personal case study of how rituals evolved through combat and eventual victory. And his work was just one part of a much bigger project: a £3.2-million (US$5-million) investigation into ritual, community and conflict, which is funded until 2016 by the UK Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) and headed by McQuinn’s supervisor, Oxford anthropologist Harvey Whitehouse.

Rituals are a human universal — “the glue that holds social groups together”, explains Whitehouse, who leads the team of anthropologists, psychologists, historians, economists and archaeologists from 12 universities in the United Kingdom, the United States and Canada. Rituals can vary enormously, from the recitation of prayers in church, to the sometimes violent and humiliating initiations of US college fraternity pledges, to the bleeding of a young man’s penis with bamboo razors and pig incisors in purity rituals among the Ilahita Arapesh of New Guinea. But beneath that diversity, Whitehouse believes, rituals are always about building community — which arguably makes them central to understanding how civilization itself began.

To explore these possibilities, and to tease apart how this social glue works, Whitehouse’s project will combine fieldwork such as McQuinn’s with archaeological digs and laboratory studies around the world, from Vancouver, Canada, to the island archipelago of Vanuatu in the south Pacific Ocean. “This is the most wide-ranging scientific project on rituals attempted to date,” says Scott Atran, director of anthropological research at the CNRS, the French national research organization, in Paris, and an adviser to the project.

Human ritesA major aim of the investigation is to test Whitehouse’s theory that rituals come in two broad types, which have different effects on group bonding. Routine actions such as prayers at church, mosque or synagogue, or the daily pledge of allegiance recited in many US elementary schools, are rituals operating in what Whitehouse calls the ‘doctrinal mode’. He argues that these rituals, which are easily transmitted to children and strangers, are well suited to forging religions, tribes, cities and nations — broad-based communities that do not depend on face-to-face contact.

Rare, traumatic activities such as beating, scarring or self-mutilation, by contrast, are rituals operating in what Whitehouse calls the ‘imagistic mode’. “Traumatic rituals create strong bonds among those who experience them together,” he says, which makes them especially suited to creating small, intensely committed groups such as cults, military platoons or terrorist cells. “With the imagistic mode, we never find groups of the same kind of scale, uniformity, centralization or hierarchical structure that typifies the doctrinal mode,” he says.

Whitehouse has been developing this theory of ‘divergent modes of ritual and religion’ since the late 1980s, based on his field work in Papua New Guinea and elsewhere. His ideas have attracted the attention of psychologists, archaeologists and historians.

Until recently, however, the theory was largely based on selected ethnographic and historical case studies, leaving it open to the charge of cherry-picking. The current rituals project is an effort by Whitehouse and his colleagues to answer that charge with deeper, more systematic data.

The pursuit of such data sent McQuinn to Libya. His strategy was to look at how the defining features of the imagistic and doctrinal modes — emotionally intense experiences shared among a small number of people, compared with routine, daily practices that large numbers of people engage in — fed into the evolution of rebel fighting groups from small bands to large brigades.

At first, says McQuinn, neighbourhood friends formed small groups comprising “the number of people you could fit in a car”. Later, fighters began living together in groups of 25–40 in disused buildings and the mansions of rich supporters. Finally, after Gaddafi’s forces were pushed out of Misrata, much larger and hierarchically organized brigades emerged that patrolled long stretches of the defensive border of the city. There was even a Misratan Union of Revolutionaries, which by November 2011 had registered 236 rebel brigades.

McQuinn interviewed more than 300 fighters from 21 of these rebel groups, which varied in size from 12 to just over 1,000 members. He found that the early, smaller brigades tended to form around pre-existing personal ties, and became more cohesive and the members more committed to each other as they collectively experienced the fear and excitement of fighting a civil war on the streets of Misrata.

But six of the groups evolved into super-brigades of more than 750 fighters, becoming “something more like a corporate entity with their own organizational rituals”, says McQuinn. A number of the group leaders had run successful businesses, and would bring everyone together each day for collective training, briefings and to reiterate their moral codes of conduct — the kinds of routine group activities characteristic of the doctrinal mode. “These daily practices moved people from being ‘our little group’ to ‘everyone training here is part of our group’,” says McQuinn.

McQuinn and Whitehouse’s work with Libyan fighters underscores how small groups can be tightly fused by the shared trauma of war, just as imagistic rituals induce terror to achieve the same effect. Whitehouse says that he is finding the same thing in as-yet-unpublished studies of the scary, painful and humiliating ‘hazing’ rituals of fraternity and sorority houses on US campuses, as well as in surveys of Vietnam veterans showing how shared trauma shaped loyalty to their fellow soldiers. [Continue reading…]

When people talk about nation-building, they talk about the need to establish security, the rule of law and the development of democratic institutions. They focus on political and civil structures through which social stability takes on a recognizable form — the operation for instance of effective court systems and law enforcement authorities that do not abuse their powers. But what makes all this work, or fail to work, is a sufficient level of social cohesion and if that is lacking, the institutional structures will probably be of little value.

Over the last year and a half, American interest in Libya seems to have been reduced to analysis about what happened on one day in Benghazi. But what might help Libya much more than America’s obsessive need to spot terrorists would be to focus instead on things like promoting football. A win for the national team could work wonders.

*

In the video below, Harvey Whitehouse describes the background to his research.

A bombed Libyan village where NATO’s ‘collateral damage’ has a name and a face

Le Monde reports: Nine months have passed but the rubble has yet to be removed. Bombed by NATO last August, the house of the Gafez family in Majer, a town about 150 kilometers east of Tripoli, still looks like a shriveled soufflé. Fourteen people died in the explosion. Twenty others died a few minutes later when bombs struck the farm of the neighbors, the Jaroods. Men, women and children, struck dead in the middle of a Ramadan evening.

What about clearing away the debris? Rebuilding? Haj Ali, the patriarch of the Gafez family never considered it. There are questions of money and of health, but also of honor, says the friendly mustachioed man. That’s because NATO doesn’t want to hear about the martyrs of Majer. The military alliance continues to insist that the bombs dropped on Aug. 8 were aimed at “legitimate military targets.”

International human rights organizations disagree. New York-based Human Rights Watch (HRW) published a well-documented report this week citing numerous errors NATO committed during its 2011 Libya campaign. According to the authors, the seven months of bombings that led to the fall of the Muammar Gaddafi regime caused the death of 72 civilians. The “relatively low” toll “shows that NATO acted with caution” all along the operation, the report states. This said, HRW laments that the military organization did not recognize its faults, did not open any probes, and did not pay any compensation to the victims of its firepower.

As an act of protest, the surviving members of the Gafez family have transformed the ruins of their house into a memorial museum. Visitors are greeted by a furious message painted on the front gate: “Is that human rights?” The words are in reference to the principle of “protecting the civilians” that French Foreign Minister Alain Juppé invoked when lobbying the U.N. Security Council to support the NATO bombing campaign. [Continue reading…]

Video: Holding NATO accountable in Libya

HRW calls on NATO to investigate civilian deaths in Libya

Human Rights Watch: The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) has failed to acknowledge dozens of civilian casualties from air strikes during its 2011 Libya campaign, and has not investigated possible unlawful attacks, Human Rights Watch said in a report released today.

The 76-page report, “Unacknowledged Deaths: Civilian Casualties in NATO’s Air Campaign in Libya,” examines in detail eight NATO air strikes in Libya that resulted in 72 civilian deaths, including 20 women and 24 children. It is based on one or more field investigations to each of the bombing sites during and after the conflict, including interviews with witnesses and local residents.

“NATO took important steps to minimize civilian casualties during the Libya campaign, but information and investigations are needed to explain why 72 civilians died,” said Fred Abrahams, special adviser at Human Rights Watch and principal author of the report. “Attacks are allowed only on military targets, and serious questions remain in some incidents about what exactly NATO forces were striking.”

NATO’s military campaign in Libya, from March to October 2011, was mandated by the United Nations Security Council to protect civilians from attacks by security forces of then-Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi.

The number of civilian deaths from NATO air strikes in Libya was low given the extent of the bombing and duration of the campaign, Human Rights Watch said. Nevertheless, the absence of a clear military target at seven of the eight sites Human Rights Watch visited raises concerns of possible laws-of-war violations that should be investigated.

Human Rights Watch called on NATO to investigate all potentially unlawful attacks and to report its findings to the UN Security Council, which authorized the military intervention in Libya.

NATO should also address civilian casualties from its air strikes in Libya at the NATO heads of state summit, taking place in Chicago on May 20 and 21, Human Rights Watch said.

The Human Rights Watch report is the most extensive examination to date of civilian casualties caused by NATO’s air campaign. It looks at all sites known to Human Rights Watch in which NATO strikes killed civilians. Strikes that resulted in no civilian fatalities – though civilians were wounded or property destroyed – were not included.

The most serious incident occurred in the village of Majer, 160 kilometers east of Tripoli, the capital, on August 8, 2011, when NATO air strikes on two family compounds killed 34 civilians and wounded more than 30, Human Rights Watch said. Dozens of displaced people were staying in one of the compounds.

A second strike outside one of the compounds killed and wounded civilians who witnesses said were searching for victims. The infrared system used by the bomb deployed should have indicated to the pilot the presence of many people on the ground. If the pilot was unable to determine that those people were combatants, then the strike should have been canceled or diverted.

Under the laws of war, parties to a conflict may only direct attacks at military targets and must take all feasible precautions to minimize harm to civilians. While civilian casualties do not necessarily mean there has been a violation of the laws of war, governments are obligated to investigate allegations of serious violations and compensate victims of unlawful attacks.

Human Rights Watch said NATO should also consider a program to provide payments to civilian victims of NATO attacks without regard to wrongdoing, as NATO has done in Afghanistan.

At seven sites documented in the report, Human Rights Watch uncovered no – or only possible – indication that Libyan military forces, weapons, hardware, or communications equipment had been present at the time of the attack. The circumstances raise serious questions about whether the buildings struck – all residential – were valid military targets. At the eighth site, at which three women and four children died, the target may have been a Libyan military officer.

NATO officials told Human Rights Watch that all of its targets were military objectives, and thus legitimate targets. But it has not provided specific information to support those claims, mostly saying a targeted site was a “command and control node” or “military staging ground.”

NATO said the Majer compounds were a “staging base and military accommodation” for Gaddafi forces, but it has not provided specific information to support that claim. During four visits to Majer, including one the day after the attack, the only possible evidence of a military presence found by Human Rights Watch was a single military-style shirt – common clothing for many Libyans – in the rubble of one of the three destroyed houses.

Family members and neighbors in Majer independently said there had been no military personnel or activity at the compounds before or at the time of the attack.

“I’m wondering why they did this; why just our houses?” said Muammar al-Jarud, who lost his mother, sister, wife, and 8-month-old daughter. “We’d accept it if we had tanks or military vehicles around, but we were completely civilians, and you can’t just hit civilians.”

To research the eight incidents, Human Rights Watch visited the sites, in some cases multiple times, inspected weapons debris, interviewed witnesses, examined medical reports and death certificates, reviewed satellite imagery, and collected photographs of the wounded and dead. Detailed questions were submitted to NATO and its member states that participated in the campaign, including in an August 2011 meeting with senior NATO officials involved in targeting.

NATO derived its mandate from UN Security Council Resolution 1973, which authorized the use of force to protect civilians in Libya. The relatively few civilian casualties during the seven-month campaign attests to the care NATO took in minimizing civilian harm, Human Rights Watch said.

Countries such as Russia that have made grossly exaggerated claims of civilian deaths from NATO air strikes during the Libyan campaign have done so without basis, Human Rights Watch said.

“The countries that have criticized NATO for so-called massive civilian casualties in Libya are trying to score political points rather than protect civilians,” Abrahams said.

NATO asserts that it cannot conduct post-operation investigations into civilian casualties in Libya because it has no mandate to operate on the ground. But NATO has not requested permission from Libya’s transitional government to look into the incidents of civilian deaths and should promptly do so, Human Rights Watch said.

“The overall care NATO took in the campaign is undermined by its refusal to examine the dozens of civilian deaths,” Abrahams said. “This is needed to provide compensation for victims of wrongful attacks, and to learn from mistakes and minimize civilian casualties in future wars.”

Women: The Libyan rebellion’s secret weapon

Joshua Hammer writes: Inas Fathy’s transformation into a secret agent for the rebels began weeks before the first shots were fired in the Libyan uprising that erupted in February 2011. Inspired by the revolution in neighboring Tunisia, she clandestinely distributed anti-Qaddafi leaflets in Souq al-Juma, a working-class neighborhood of Tripoli. Then her resistance to the regime escalated. “I wanted to see that dog, Qaddafi, go down in defeat.”

A 26-year-old freelance computer engineer, Fathy took heart from the missiles that fell almost daily on Col. Muammar el-Qaddafi’s strongholds in Tripoli beginning March 19. Army barracks, TV stations, communications towers and Qaddafi’s residential compound were pulverized by NATO bombs. Her house soon became a collection point for the Libyan version of meals-ready-to-eat, cooked by neighborhood women for fighters in both the western mountains and the city of Misrata. Kitchens across the neighborhood were requisitioned to prepare a nutritious provision, made from barley flour and vegetables, that could withstand high temperatures without spoiling. “You just add water and oil and eat it,” Fathy told me. “We made about 6,000 pounds of it.”

Fathy’s house, located atop a hill, was surrounded by public buildings that Qaddafi’s forces often used. She took photographs from her roof and persuaded a friend who worked for an information-technology company to provide detailed maps of the area; on those maps, Fathy indicated buildings where she had observed concentrations of military vehicles, weapons depots and troops. She dispatched the maps by courier to rebels based in Tunisia.

On a sultry July evening, the first night of Ramadan, Qaddafi’s security forces came for her. They had been watching her, it turned out, for months. “This is the one who was on the roof,” one of them said, before dragging her into a car. The abductors shoved her into a dingy basement at the home of a military intelligence officer, where they scrolled through the numbers and messages on her cellphone. Her tormentors slapped and punched her, and threatened to rape her. “How many rats are working with you?” demanded the boss, who, like Fathy, was a member of the Warfalla tribe, Libya’s largest. He seemed to regard the fact that she was working against Qaddafi as a personal affront.

The men then pulled out a tape recorder and played back her voice. “They had recorded one of my calls, when I was telling a friend that Seif al-Islam [one of Qaddafi’s sons] was in the neighborhood,” recalls Fathy. “They had eavesdropped, and now they made me listen to it.” One of them handed her a bowl of gruel. “This,” he informed her, “will be your last meal.” [Continue reading…]

UN report faults NATO’s response to civilian toll and Libya’s failure to curb violence

The New York Times reports: NATO has not sufficiently investigated the air raids it conducted on Libya that killed at least 60 civilians and wounded 55 more during the conflict there, according to a new United Nations report released Friday.

Nor has Libya’s interim government done enough to halt the disturbing violence perpetrated by revolutionary militias seeking to exact revenge on loyalists, real or perceived, to the government of Col. Muammar el-Qaddafi, the report concluded.

Published without publicity on the Web site of the United Nations Human Rights Council, based in Geneva, the report details the results of an investigation by a three-member commission of distinguished jurists. It paints a generally gloomy picture of the level of respect for human rights and international law in Libya, while acknowledging that the problem is a legacy of the long years of violent repression under Colonel Qaddafi.

NATO air raids that killed civilians in Libya have been criticized by rights groups, and the alliance’s refusal to acknowledge or investigate some of the deaths has been the subject of earlier news reports, including an extensive account in The New York Times last December. The new report represents the first time that NATO’s actions in Libya have been criticized under the auspices of the United Nations, where the bombing campaign in the name of protecting civilians from Colonel Qaddafi’s forces was authorized by the Security Council.

The report concluded that Colonel Qaddafi’s forces had perpetuated war crimes and crimes against humanity, including murder, torture and attacks on civilians using excessive force and rape.

But the armed anti-Qaddafi militia forces in Libya also “committed serious violations,” including war crimes and breaches of international rights law that continue today, the 220-page report said.

In post-Gaddafi Libya, freedom is messy — and getting messier

Tony Karon writes: “I fear this looks like a civil war”, one Libyan rebel commander from Misrata told the Associated Press, in the wake of a fierce firefight between rival militia factions using heavy weapons in broad daylight in Tripoli on Tuesday. Four fighters were reportedly killed and five wounded in the clash ignited by the attempts of a Misrata-based militia to free a comrade detained by the Tripoli Military Council on suspicion of theft. But such clashes have become increasingly common in the Libyan capital over the past two months, as rival militias stake out turf in the power vacuum caused by the collapse of the Gaddafi regime. And while leaders on both sides of Tuesday’s clash were eventually able to broker a cease-fire, the deep fissures of tribe, region, ideology and sometimes even neighborhood that divide rival armed groups persist —and there’s no sign yet of the emergence of a central political authority with the military muscle to enforce its writ.

The residents and militias of Tripoli have been trying for months to persuade the Misrata and Zintan fighters who stormed the capital to topple the regime to go back to their home towns, but those fighters are staying put—and are accused of harassing the locals. They see themselves as the ones who shouldered the greatest burden in the battle to drive out Gaddafi, and they are suspicious of edicts by the National Transitional Council (NTC), which they see as self-appointed interlopers from Benghazi (the NTC’s recognition by the West and Arab governments as Libya’s legitimate government notwithstanding). The fighters of Zintan and Misrata are in no hurry to subordinate themselves to a national army led by returned exiles and a government of which they’re wary; nor are they willing to accept the authority of the Tripoli Military Council headed by the Islamist Abdel Hakim Belhadj, despite his endorsement by the NTC. Mindful of the political power that flows from being armed and organized, and determined to leverage that into a greater share of power and resources for the regions and towns they claim to represent, the regional militias are in no rush to give up their control of prized political real estate. They’ve ignored the Dec. 20 deadline to leave Tripoli. And, when NTC-backed armed groups tangle with them, as happened with the New Year’s Eve arrest of some of their men, they’re willing to fight.

The Cafe – Libya: When the impossible became possible

In his first interview, Saif al-Islam says he has not been given access to a lawyer

Human Rights Watch’s Fred Abrahams writes: The guards in the remote Libyan town of Zintan called their prisoner, Saif al-Islam Gaddafi, “our black box.” The second-oldest son of Muammar Gaddafi knew the secrets of Libya’s past, they said: Gaddafi’s deals with foreign governments and companies, the whereabouts of still-missing prisoners, the details of crimes committed during the regime’s failed attempt to crush this year’s popular revolt. Saif al-Islam, 39, had to be protected so Libyans and the world could learn what had really taken place. And for the guards in Zintan, a town of 50,000 atop a desert mountain, keeping Libya’s most-wanted man safe from the sort of frenzied opposition fighters who had apparently executed Saif’s father and brother Mutassim also offered a chance to patch up the country’s reputation for justice after the Oct. 20 killing of Muammar Gaddafi.

As a special adviser for Human Rights Watch, I had arranged with the new Libyan government to interview Saif about the conditions of his detention after his arrest on Nov. 19 in the far south of his country. The International Committee of the Red Cross had visited four days into his detention, issuing a typically terse statement, and the public had not seen or heard from him since.

Saif entered the room draped in a large brown woolen cape with an embroidered fringe. He extended his left hand, keeping his right hand hidden beneath the cape. “Welcome to Zintan,” he said with an ironic smile, eliciting a chuckle from his captors and from me. The smile was bright. But Saif had lost the flair that I’d seen on television and heard about from those who had met him before. He had a scraggly beard and his once clean-shaven head was ringed by a horseshoe of graying hair. The setting was not what Libya’s heir-apparent would have been used to: a dimly lit room with a faded carpet and cushions along the edge. Two years ago he threw a lavish party for his 37th birthday on the coast of Montenegro; guests, reportedly, included Russian billionaire Oleg Deripaska and Prince Albert of Monaco.

Saif joked casually with the guards. “Ohhh, very good,” he said when they gave him his rimless glasses, which had been taken to Tripoli for repair. I thought his nonchalance suggested that he failed to grasp the gravity of his situation. Or maybe that’s how a person acts when born into a dictator’s family and is accustomed to solving all problems with orders or money.

Dan Ephron reports: Aisha Gaddafi, the daughter of the late Libyan dictator, is asking the International Criminal Court to investigate the killing of her father and her brother Mutassim by Libyan opposition forces in October, suggesting that the rebels, together with NATO forces, may be guilty of war crimes.

The petition raises legal questions about the nine-month insurgency that toppled Muammar Gaddafi and, indirectly at least, about the role American troops played as part of NATO.

But it has garnered attention for another reason as well: Aisha’s lawyer is from Israel, a country Muammar Gaddafi refused to recognize and often described as illegitimate.

Vengeance in Libya

Joshua Hammer writes: On November 20, the day after the capture of Seif Qaddafi, the second son and former heir apparent of Muammar Qaddafi, I set out from Tripoli for Libya’s Nafusa Mountains, to meet some of the former rebels who had tracked him down. I left the seaside capital just after dawn, followed the coastal road west, then turned inland. There were many signs of the recent civil war on the arid plain: craters formed by the impact of 122-millimeter Grad rockets, destroyed communications towers, crumpled armored vehicles struck by NATO bombs. Unexploded ordnance lay everywhere. My driver-translator, Wagde Bargig, said that “children have been killed playing” in the fields we passed.

Bargig comes from the town of Nalut in the Nafusa Mountains, the home of the Amazigh, or Berbers, a non-Arab tribe that was long oppressed by Muammar Qaddafi. Employed as a dental technician until the uprising began in late February, he had one week of weapons instruction from defecting government officers, then joined the fight against the dictatorship. “We chased out the army and the police, burned down government buildings, put up roadblocks, evacuated the women and children to Tunisia, and then held the town,” he told me. “Qaddafi’s forces bombarded us with Grad rockets, and many people were killed, but they couldn’t enter Nalut.” Afterward many Berbers, including Bargig, had taken part in the western offensive, fighting alongside Arab rebels from the Zintan Brigade—the rebel group from the town of Zintan that had just captured Seif Qaddafi—in a display of interethnic unity.

Now that the war was over, he told me, solidarity had begun to break up. One point of disagreement among the ex-fighters was how to deal with their prisoners, who number about seven thousand, according to a United Nations report published in November. Some former rebels were turning over captured soldiers to the National Transitional Council in Tripoli; others were jealously guarding them—or freeing them unilaterally, as the Berbers had. “In Nalut,” Bargig told me, “they released all three hundred soldiers, at Eid.” There had been a general amnesty but it had been unpopular: “People said, ‘They were shelling us, killing us, and you let them go back to their families.’” The inconsistent approaches typified the disorganization and fragmentation that plague postwar Libya. “Nobody’s in control,” he said.