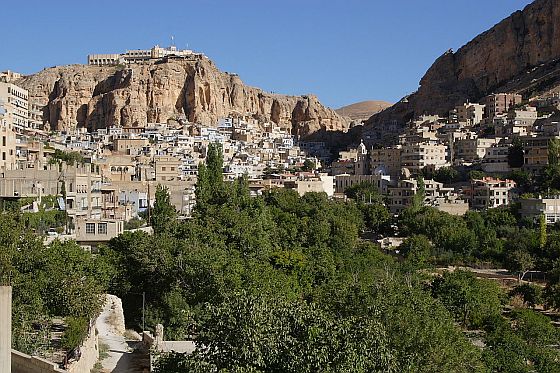

The Christian village of Maaloula, in the hills outside Damascus, Syria, the last remaining community where Aramaic is maintained as an everyday language.

Aramaic, once the common language of the entire Middle East, is one or two generations away from extinction. Ariel Sabar writes: It was a sunny morning in May, and I was in a car with a linguist and a tax preparer trolling the suburbs of Chicago for native speakers of Aramaic, the 3,000-year-old language of Jesus.

The linguist, Geoffrey Khan of the University of Cambridge, was nominally in town to give a speech at Northwestern University, in Evanston. But he had another agenda: Chicago’s northern suburbs are home to tens of thousands of Assyrians, Aramaic-speaking Christians driven from their Middle Eastern homelands by persecution and war. The Windy City is a heady place for one of the world’s foremost scholars of modern Aramaic, a man bent on documenting all of its dialects before the language — once the tongue of empires — follows its last speakers to the grave.

The tax preparer, Elias Bet-shmuel, a thickset man with a shiny pate, was a local Assyrian who had offered to be our sherpa. When he burst into the lobby of Khan’s hotel that morning, he announced the stops on our two-day trek in the confidential tone of a smuggler inventorying the contents of a shipment.

“I got Shaqlanaye, I have Bebednaye.” He was listing immigrant families by the names of the northern Iraqi villages whose dialects they spoke. Several of the families, it turned out, were Bet-shmuel’s clients.

As Bet-shmuel threaded his Infiniti sedan toward the nearby town of Niles, Illinois, Khan, a rangy 55-year-old, said he was on safari for speakers of “pure” dialects: Aramaic as preserved in villages, before speakers left for big, polyglot cities or, worse, new countries. This usually meant elderly folk who had lived the better part of their lives in mountain enclaves in Iraq, Syria, Iran or Turkey. “The less education the better,” Khan said. “When people come together in towns, even in Chicago, the dialects get mixed. When people get married, the husband’s and wife’s dialects converge.”

We turned onto a grid of neighborhood streets, and Bet-shmuel announced the day’s first stop: a 70-year-old widow from Bebede who had come to Chicago just a decade earlier. “She is a housewife with an elementary education. No English.”

Khan beamed. “I fall in love with these old ladies,” he said.

Aramaic, a Semitic language related to Hebrew and Arabic, was the common tongue of the entire Middle East when the Middle East was the crossroads of the world. People used it for commerce and government across territory stretching from Egypt and the Holy Land to India and China. Parts of the Bible and the Jewish Talmud were written in it; the original “writing on the wall,” presaging the fall of the Babylonians, was composed in it. As Jesus died on the cross, he cried in Aramaic, “Elahi, Elahi, lema shabaqtani?” (“My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”)

But Aramaic is down now to its last generation or two of speakers, most of them scattered over the past century from homelands where their language once flourished. In their new lands, few children and even fewer grandchildren learn it. (My father, a Jew born in Kurdish Iraq, is a native speaker and scholar of Aramaic; I grew up in Los Angeles and know just a few words.) This generational rupture marks a language’s last days. For field linguists like Khan, recording native speakers — “informants,” in the lingo — is both an act of cultural preservation and an investigation into how ancient languages shift and splinter over time.

In a highly connected global age, languages are in die-off. Fifty to 90 percent of the roughly 7,000 languages spoken today are expected to go silent by century’s end. We live under an oligarchy of English and Mandarin and Spanish, in which 94 percent of the world’s population speaks 6 percent of its languages. Yet among threatened languages, Aramaic stands out. Arguably no other still-spoken language has fallen farther. [Continue reading…]