In 2014, Malise Ruthven wrote: When the jihadists of ISIS (the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria) tweeted pictures of a bulldozer crashing through the earthen barrier that forms part of the frontier between Syria and Iraq, they announced — triumphantly — that they were destroying the “Sykes-Picot” border. The reference to a 1916 Franco-British agreement about the Middle East may seem puzzling, coming from a radical group fighting a brutal ethnic and religious insurgency against Bashar al-Assad’s Syria and Nouri al-Maliki’s Iraq. But jihadist groups have long drawn on a fertile historical imagination, and old grievances about the West in particular.

This symbolic action by ISIS fighters against a century-old imperial carve-up shows the extent to which one of the most radical groups fighting in the Middle East today is nurtured by the myth of precolonial innocence, when the Ottoman Empire and Sunni Islam ruled over an unbroken realm from North Africa to the Persian Gulf and the Shias knew their place. (Indeed, the Arabic name of ISIS — al-Dawla al-Islamiya fil-Iraq wa al-Sham — refers to a historic idea of the greater Levant (al-Sham) that transcends the region’s modern, Western-imposed state borders.)

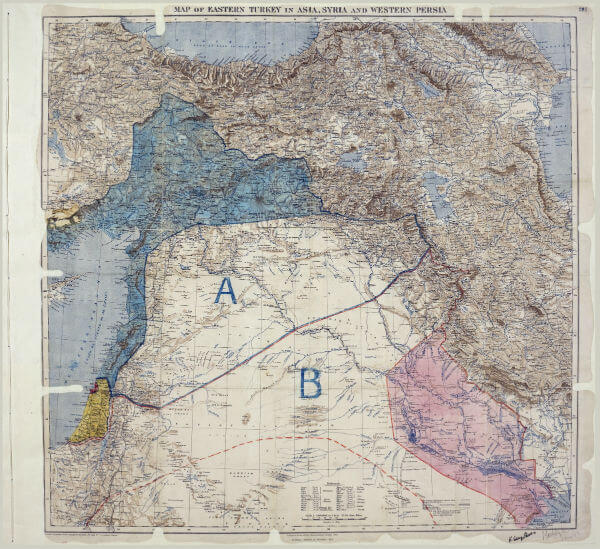

But why is Sykes-Picot so important? One reason is that it stands near the beginning of what many Arabs view as a sequence of Western betrayals spanning from the dismantling of the Ottoman Empire in World War I to the establishment of Israel in 1948 and the 2003 invasion of Iraq. The Sykes-Picot agreement — named after the British and French diplomats who signed it — was entered in secret, with Russia’s assent, in May 1916 to divide the Arab provinces of the Ottoman Empire into British and French “spheres of influence.” It designated each power’s areas of future control in the event of victory by the Triple Entente over Germany, Austria, and their Ottoman ally. Under the agreement Britain was allocated the coastal strip between the Mediterranean and the river Jordan, Transjordan and southern Iraq, with enclaves including the ports of Haifa and Acre, while France was allocated south-eastern Turkey, northern Iraq, all of Syria and Lebanon. Russia was to get Istanbul, the Dardanelles, and the Ottoman Empire’s Armenian districts.

Under the 1920 San Remo agreement, which built on Sykes-Picot, the Western powers were free to decide on state boundaries within these areas. The international frontiers — with Iraq’s framed by the merging of the three Ottoman vilayets of Mosul, Baghdad, and Basra — were consolidated by the separate mandates granted by the League of Nations to France in Lebanon and Syria, and to Britain in Palestine, Transjordan, and Iraq. The frontier between French-controlled Syria and British-controlled Iraq included the desert of Anbar province that was bulldozed by ISIS this month.

Kept hidden for more than a year, the Anglo-French pact caused a furor when it was first revealed by the Bolsheviks after the 1917 Russian Revolution — with the Syrian Congress, convened in July 1919, demanding “the full freedom and independence that had been promised to us.” Not only did the agreement map out — unbeknownst to the Arab leaders of the time — a new system of Western control of local populations. It also directly contradicted the promise that Britain’s man in Cairo, Sir Henry McMahon, had made to the ruler of Mecca, the Sharif Hussein, that he would have an Arab kingdom in the event of Ottoman defeat. In fact, that promise itself, which had been conveyed in McMahon’s correspondence with the Sharif between July 1915 and January 1916, left ambiguous the borders of the future Arab state, and was later used to deny Arab control of Palestine. McMahon had excluded from the proposed Arab kingdom “portions of Syria lying to the west of the districts of Damascus, Homs, Hama and Aleppo [that] cannot be said to be purely Arab.” This clause led to lengthy and bitter debates as to whether Palestine — which Britain meanwhile promised as a homeland for Jews under the terms of the November 1917 Balfour Declaration — could be defined as lying “west” of the vilayet, or district, of Damascus. [Continue reading…]