Paul Harris writes: The British empire never lacked contradictions. A global juggernaut standing with its military boot on millions of necks, practising commercial coercion and diplomatic cynicism, it nonetheless routinely thought of itself as a plucky underdog. Its heroes were the handful of redcoats at Rorke’s Drift fighting off the Zulu masses, or General Charles Gordon of Khartoum, going down against the odds in a last stand against religious zealots in the Sudan.

British soldiers, diplomats and traders pictured themselves as almost accidental conquerors, vanquishing a quarter of the planet’s landmass in between tea, tiffin and cricket matches. They maintained a detached stiff upper lip and publicly ignored the unpleasant reality of the Maxim gun – a luxury not afforded to the locals on its business end.

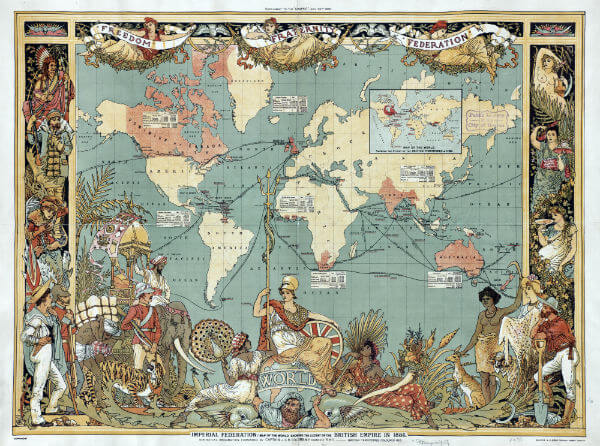

Britain preferred to see its dominance of a fifth of the world’s population as some sort of benevolent, God-given mission to bring law, order and free trade to benighted corners of the world. As George Bernard Shaw complained: ‘The ordinary Britisher imagines that God is an Englishman.’

It was a powerful notion and it has not gone away. Even though the Empire is reduced to a scattering of tiny islands with names few Britons would recognise, the imperial past remains implausibly popular. Early this year, a poll showed that a full 44 per cent of Britons were proud of colonialism, far outnumbering the mere 21 per cent who regretted their country’s imperial past. The survey was not an outlier. A 2014 report showed a mere 15 per cent of Britons thought the colonised might just have been left worse off by the experience. [Continue reading…]