Category Archives: remote warfare

Drone warfare and the stress induced by premeditated murder

A recent study by the U.S. Air Force School of Aerospace Medicine assessed the level of stress involved in remote warfare being conducted by Air Force drone operators. The New York Times reports:

4 percent or less of operators were at high risk of developing post-traumatic stress disorder, the severe anxiety disorder that can include flashbacks, nightmares, anger, hypervigilance or avoidance of people, places or situations. In those cases, the authors suggested, the operators had seen close-up video of what the military calls collateral damage, casualties of women, children or other civilians. “Collateral damage is unnerving or unsettling to these guys,” Colonel McDonald said.

The percentage of troops returning from Iraq and Afghanistan at risk of developing post-traumatic stress disorder was 12 to 17 percent, the authors said.

In contrast to nearly half of drone operators’ reporting “high operational stress,” 36 percent of a control group of 600 Air Force members in logistics or support jobs reported stress. The Air Force did not compare the stress levels of the drone operators with military pilots who fly planes in the air.

The biggest sources of stress for drone operators remained long hours and frequent shift changes because of staff shortages.

Glenn Greenwald comments:

[A]t least some of these drone pilots have enough of a conscience to be seriously disturbed by the horrific results of these strikes. If only the general citizenry — who are typically kept blissfully unaware of the human devastation their government is causing — were as affected.

But to suggest that a measure of conscience is the way these pilots react to the unintended effects of their actions, doesn’t really say much about what is going on here.

In a recent edition of “The Stream” on Al Jazeera, former CentCom spokesman Josh Rushing, made these observations. (Watch the following video from 20min 22 sec till 21min 22sec.)

As unprecedented as it might seem for a killer to so closely study his target, this really isn’t new. Indeed, there is a commonly used term we associate with this kind of planning: premeditation.

Murder of the worst kind involves cold calculation and emotional detachment. The idea that a drone operator might end up with PTSD simply as a result of seeing innocent people get killed, ignores the effect of his spending hours or days anticipating an intentional killing.

The military precursor of the drone operator is the sniper and the non-military correlate of both is the hitman.

Randall Collins notes that inside the military, the sniper stands apart.

Snipers tend to be disliked even by their fellow soldiers, or at least regarded with uneasiness. A British sniper officer in World War I noted that infantrymen did not like to mingle with the snipers “for there was something about them that set them apart from ordinary men and made the soldiers uncomfortable”… World War II soldiers sometimes jeered at them. U.S. snipers in Vietnam were met with the comment: “Here comes Murder Incorporated.”

Josh Rushing notes that the Pentagon’s shift in favor of remote warfare is a reflection of a political reality: that if Americans are not taxed to support this country’s wars, and if wars can be fought without American soldiers getting killed, then Washington faces few political constraints in starting new wars about which the public will show little interest.

The Air Force is now recruiting more drone pilots than fighter and bomber pilots combined, but the continued success in recruitment requires that the job of these armchair pilots be glamorized and tied into a traditional warfighting culture. Hence the creation of commercials like this:

But note the irony: the stated target in this portrayal of 21st century warfare is the “enemy sniper” and the role of the drone pilot is to protect ordinary American soldiers.

In the battlefields that the Pentagon prefers however, there are no American soldiers, death comes by decree and those getting killed — however they might be labelled — are utterly defenseless.

The secret program empowering Obama to kill anyone, anywhere, without any explanation

The Washington Post reports: Since September, at least 60 people have died in 14 reported CIA drone strikes in Pakistan’s tribal regions. The Obama administration has named only one of the dead, hailing the elimination of Janbaz Zadran, a top official in the Haqqani insurgent network, as a counterterrorism victory.

The identities of the rest remain classified, as does the existence of the drone program itself. Because the names of the dead and the threat they were believed to pose are secret, it is impossible for anyone without access to U.S. intelligence to assess whether the deaths were justified.

The administration has said that its covert, targeted killings with remote-controlled aircraft in Pakistan, Yemen, Somalia and potentially beyond are proper under both domestic and international law. It has said that the targets are chosen under strict criteria, with rigorous internal oversight.

It has parried reports of collateral damage and the alleged killing of innocents by saying that drones, with their surveillance capabilities and precision missiles, result in far fewer mistakes than less sophisticated weapons.

Yet in carrying out hundreds of strikes over three years — resulting in an estimated 1,350 to 2,250 deaths in Pakistan — it has provided virtually no details to support those assertions.

In outlining its legal reasoning, the administration has cited broad congressional authorizations and presidential approvals, the international laws of war and the right to self-defense. But it has not offered the American public, uneasy allies or international authorities any specifics that would make it possible to judge how it is applying those laws. [Continue reading…]

Iran says its delayed news of U.S. drone capture

The Associated Press reports: Iran deliberately delayed its announcement that it had captured an American surveillance drone to test U.S. reaction, the country’s foreign minister said Saturday.

Ali Akbar Salehi said Tehran finally went public with its possession of the RQ-170 Sentinel stealth drone to disprove contradictory statements from U.S. officials.

Iran, which put the aircraft on display last week, has tried to trumpet the downing of the drone as a feat of Iran’s military in a complicated technological and intelligence battle with the U.S. Tehran also has rejected a formal U.S. request to return the plane, calling it’s incursion an “invasion” and a “hostile act.”

“When our armed forces nicely brought down the stealth American surveillance drone, we didn’t announce it for several days to see what the other party (U.S.) says and to test their reaction,” Salehi told the official IRNA news agency. “Days after Americans made contradictory statements, our friends at the armed forces put this drone on display.”

Iran hijacked U.S. drone, says Iranian engineer

Christian Science Monitor reports in an exclusive: Iran guided the CIA’s “lost” stealth drone to an intact landing inside hostile territory by exploiting a navigational weakness long-known to the US military, according to an Iranian engineer now working on the captured drone’s systems inside Iran.

Iranian electronic warfare specialists were able to cut off communications links of the American bat-wing RQ-170 Sentinel, says the engineer, who works for one of many Iranian military and civilian teams currently trying to unravel the drone’s stealth and intelligence secrets, and who could not be named for his safety.

Using knowledge gleaned from previous downed American drones and a technique proudly claimed by Iranian commanders in September, the Iranian specialists then reconfigured the drone’s GPS coordinates to make it land in Iran at what the drone thought was its actual home base in Afghanistan.

“The GPS navigation is the weakest point,” the Iranian engineer told the Monitor, giving the most detailed description yet published of Iran’s “electronic ambush” of the highly classified US drone. “By putting noise [jamming] on the communications, you force the bird into autopilot. This is where the bird loses its brain.”

The “spoofing” technique that the Iranians used – which took into account precise landing altitudes, as well as latitudinal and longitudinal data – made the drone “land on its own where we wanted it to, without having to crack the remote-control signals and communications” from the US control center, says the engineer.

The revelations about Iran’s apparent electronic prowess come as the US, Israel, and some European nations appear to be engaged in an ever-widening covert war with Iran, which has seen assassinations of Iranian nuclear scientists, explosions at Iran’s missile and industrial facilities, and the Stuxnet computer virus that set back Iran’s nuclear program.

Now this engineer’s account of how Iran took over one of America’s most sophisticated drones suggests Tehran has found a way to hit back. The techniques were developed from reverse-engineering several less sophisticated American drones captured or shot down in recent years, the engineer says, and by taking advantage of weak, easily manipulated GPS signals, which calculate location and speed from multiple satellites.

Western military experts and a number of published papers on GPS spoofing indicate that the scenario described by the Iranian engineer is plausible.

“Even modern combat-grade GPS [is] very susceptible” to manipulation, says former US Navy electronic warfare specialist Robert Densmore, adding that it is “certainly possible” to recalibrate the GPS on a drone so that it flies on a different course. “I wouldn’t say it’s easy, but the technology is there.”

CIA drones quit one Pakistan site — but U.S. keeps access to other airbases

The Bureau of Investigative Journalism reports: Despite its very public withdrawal from Shamsi airfield at the weekend, the United States continues to have access to a number of military airfields inside Pakistan – including at least one from which armed drones are able to operate, the Bureau understands.

The first concrete indications have also emerged that the US has now effectively suspended its drone strikes in Pakistan. The Bureau’s own data registers no CIA strikes since November 17.

Islamabad is furious in the wake of a NATO attack which recently killed 24 Pakistani soldiers on its Afghan borders. As well as suspending NATO supply convoys through Pakistan, anti-aircraft missiles have also reportedly been moved to the border with Afghanistan. Pakistan also demanded that the US withdraw from Shamsi, a major airfield in Balochistan controlled and run by the Americans since late 2001.

US Predator and Reaper drones have operated from the isolated airbase for many years. Technically the base is leased to Abu Dhabi in the United Arab Emirates, which allowed Pakistan to deny a US presence for many years. Now the US has quit Shamsi, with large US transporter planes stripping military hardware from the base.

But the US will continue to have access to at least five other Pakistani military facilities, according to a Pakistani source with extensive knowledge of US-Pakistani military and intelligence co-operation.

New evidence that Iran hijacked U.S. stealth drone — updated

Updated: I guess the egg’s on my face this time. Turns out the video the Iranians broadcast (see below) is not an RQ-170 — it’s a Lockheed Polecat on a test flight. (Thanks goes to reader “blowback” for pointing this out.)

As the story about Iran’s capture of an RQ-170 stealth drone continues to unfold, it is the credibility of American officials that keeps on getting shredded.

Here’s the latest from the Associated Press:

Officers in the Revolutionary Guard, Iran’s most powerful military force, have claimed the country’s armed forces brought down the surveillance aircraft with an electronic ambush, causing minimum damage to the drone.

American officials have said that U.S. intelligence assessments indicate that Iran neither shot the drone down, nor used electronic or cybertechnology to force it from the sky. They contend the drone malfunctioned.

Is this how a malfunctioning drone makes a perfect landing on an Iranian airstrip?

President Obama says the U.S. has asked for its drone back. But Iran has no intention of returning it and claims to be in the final stages of extracting data from it according to one lawmaker.

The Washington Post reports:

Parviz Sorouri, a key member of the parliament’s national security and foreign policy committee, told Iranian state television that the extracted information would be used to file a lawsuit against the United States over the “invasion” by the unmanned aircraft.

He asserted that Iran would “soon” start to reproduce the drone after a nearly finished process of reverse engineering was completed. “In the near future, we will be able to mass produce it. . . . Iranian engineers will soon build an aircraft superior to the American [drone] using reverse engineering,” he was quoted as saying.

Sorouri also said the country’s armed forces would soon conduct an exercise on closing the Strait of Hormuz, the narrow waterway between the Gulf of Oman and the oil-rich Persian Gulf.

Noting the strategic importance of the strait, Sorouri said, “We will hold a military maneuver on how to close the Strait of Hormuz soon,” the Iranian Students’ News Agency reported. “If the world wants to make the region insecure, we will make the world insecure.”

Increased U.S. drone strikes questioned

Satellite images reveal secret Nevada drone site

What appears to be a General Atomics MQ-1 Predator or MQ-9 Reaper UAV being towed on the parking ramp, Yucca Lake, Nevada.

Flightglobal reports: A new satellite image of an isolated airstrip in Nevada shows a secret but operational unmanned air vehicle (UAV) test facility. The Yucca Lake airfield, deep inside the heavily restricted Tonopah Test Range, is on land owned by the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), a division of the Department of Energy (DoE), but was constructed and operated by an undisclosed government customer.

The satellite image, taken in early 2011 and available on Google Maps, appears to show a roughly 5,200 ft (1,580m) asphalt runway and what appears to be a General Atomics MQ-1 Predator or MQ-9 Reaper UAV being towed on the parking ramp. The airfield has four hangers of varying sizes, including a hanger with clamshell doors that is characteristic of US UAV operations. Details of the airfield, including a parking lot, security perimeter and ongoing construction are clearly visible.

The hangers could accommodate a total of between 10-15 MQ-9 Reaper aircraft, according to Tim Brown, an imagery analyst with Globalsecurity.org.

U.S. made covert plan to retrieve Iran drone

The Wall Street Journal reports: U.S. officials considered conducting a covert mission inside Iran to retrieve or destroy a stealth drone that crashed late last week, but ultimately concluded such a secret operation wasn’t worth the risk of provoking a more explosive clash with Tehran, a U.S. official said…

The officials considered various options for retrieving the wreckage of the RQ-170 drone.

Under one plan, a team would be sent to retrieve the aircraft. U.S. officials considered both sending in a team of American commandos based in Afghanistan as well as using allied agents inside Iran to hunt down the downed aircraft.

Another option would have had a team sneak in to blow up the remaining pieces of the drone. A third option would have been to destroy the wreckage with an airstrike.

However, the officials worried that any option for retrieving or destroying the drone would have risked discovery by Iran.

“No one warmed up to the option of recovering it or destroying it because of the potential it could become a larger incident,” the U.S. official said.

If an assault team entered the country to recover or destroy the drone, the official said, the U.S. “could be accused of an act of war” by the Iranian government.

The New York Times adds: The stealth C.I.A. drone that crashed deep inside Iranian territory last week was part of a stepped-up surveillance program that has frequently sent the United States’ most hard-to-detect drone into the country to map suspected nuclear sites, according to foreign officials and American experts who have been briefed on the effort.

Until this week, the high-altitude flights from bases in Afghanistan were among the most secret of many intelligence-collection efforts against Iran, and American officials refuse to discuss it. But the crash of the vehicle, which Iranian officials said occurred more than 140 miles from the border with Afghanistan, blew the program’s cover.

The overflights by the bat-winged RQ-170 Sentinel, built by Lockheed Martin and first glimpsed on an airfield in Kandahar, Afghanistan, in 2009, are part of an increasingly aggressive intelligence collection program aimed at Iran, current and former officials say.

CIA has operated fleet of stealth drones spying on Iran for years

The Associated Press reports: U.S. officials say a drone that crashed inside Iran over the weekend was one of a fleet of stealth aircraft that have spied on Iran for years from a U.S. air base in Afghanistan.

They say the CIA stealth-version of the RQ-170 unmanned craft was also used to survey Osama bin Laden’s compound before the May raid in Pakistan.

According to these officials, the U.S. has built up the air base Shindad, Afghanistan, with an eye to keeping a long-term presence there to launch surveillance missions and even special operations missions into Iran if deemed necessary.

In July, the US Air Force reported: By expanding to nearly three times its original size, Shindand Air Base recently became the second largest airfield throughout Afghanistan.

Colonel Larry Bowers, the 838th Air Expeditionary Advisory Group commander, opened the new expansion area upon completion of construction of approximately eight miles of perimeter fence line.

Having been in the works since fall of 2010, completion of the “Far East Expansion” makes the base second only to Bastion Field in Lashkar Gah in size.

The project is part of a $500 million military construction effort to support Regional Command West and turn Shindand AB into the premier flight-training base in Afghanistan, officials said.

The new expansion is slated to become the new living and working area for more than 3,000 coalition forces and government contractors, officials said. The relocation of these members will make room for a new a 1.3-mile NATO training runway, with construction scheduled to begin in early 2012.

Iran captures ‘lost’ U.S. spy drone — the first remote hijacking?

The Los Angeles Times reports:

A drone that Iranian officials claimed to have shot down may be an unarmed U.S. reconnaissance aircraft that went missing over western Afghanistan late last week, according to U.S.-led forces in that country.

“The operators of the UAV [unmanned aerial vehicle] lost control of the aircraft and had been working to determine its status,” NATO’s International Security Assistance Force in Afghanistan said in a statement.

Iranian media reported Sunday that the country’s armed forces had shot down a U.S. drone that they said violated Iranian airspace along the eastern border. Iran borders Afghanistan and Pakistan in the east.

An Iranian military official quoted by the official Islamic Republic News Agency said the aircraft suffered minor damage and was in the possession of the armed forces. He identified the aircraft as an “RQ170” type drone and said Iranian forces were “fully ready to counter any aggression.”

When the existence of the RQ-170 first entered the public domain after it was photographed in Afghanistan, it quickly got dubbed the “Beast of Kandahar.”

As a highly classified stealth aircraft the question was: why would the US be flying a drone designed to evade radar when the Taliban have no radar? Speculation suggested that its areas of operation were more likely over Pakistan and perhaps spying on nuclear facilities in Iran.

In May this year the Washington Post reported that this aircraft had indeed been used to “fly dozens of secret missions deep into Pakistani airspace and monitor the compound where Osama bin Laden was killed.”

So how did the operators manage to lose such valuable piece of equipment last week? Someone fell asleep at the wheel? Very unlikely during such a critical intelligence operation. A technical malfunction? Maybe, but in such an event it would seem more likely that the aircraft would have crashed and been destroyed.

Another possibility is that “lost control” is another way of saying hijacked. In other words, U.S. remote pilots lost control as Iranians took control.

There maybe a connection with another drone story — this one about a drone that Israel lost.

Late last month, Richard Silverstein “revealed” that an Israeli drone brought down over Southern Lebanon by Hezbollah had been booby-trapped and later unwittingly taken to a weapons depot where it was remotely detonated. It was a story so implausible that it seemed like Israeli intelligence could only feed it to a scoop-hungry blogger since most journalists simply wouldn’t take it seriously.

If the story was indeed an Israeli fabrication then it was probably concocted in order to cover up a much more important story: that Hezbollah has managed to refine its tools of electronic warfare to a point that puts in jeopardy all of Israel’s drone missions over Lebanon.

If that was the case this would have serious consequences since it is widely assumed that in the event of an Israeli attack on Iran’s nuclear facilities, reprisal attacks on Israel from Lebanon would swiftly follow. In such a situation, Israel could not afford to have lost one of its most valuable intelligence gathering tools — the means on which it might depend to prevent missile strikes on Tel Aviv.

In other words, if Israel’s ability to defend itself from attacks from Lebanon has been significantly degraded, it might need to be a bit more cautious about threatening to attack Iran.

Israel is flying less sophisticated drones than the RQ-170, but even so, whatever skills Hezbollah has been acquiring in its counter-drone operations it has very likely been sharing with Iran’s Revolutionary Guard.

Might this provide part of the explanation about how the U.S. lost and Iran found a drone that supposedly went “missing”?

The romance of remote warfare

The U.S. Air Force now recruits more pilots for drones than fighter and bomber pilots combined, says Air Force Maj. Gen. James Poss who helps oversee the Air Force’s surveillance programs.

In an interview with National Public Radio, Poss alludes to the fact that in the early years of remote warfare, piloting drones did not appeal to military recruits who saw themselves instead becoming battle-tested warriors. But as the commercial above makes clear, the Air Force is now working hard to incorporate Predators and their pilots into the combat ethos.

Unlike a person that deploys to combat, our remotely piloted aircraft force never leave combat and that’s got unique psychological stresses — you really don’t get a break. And even more jarring is you do leave your ground control station and drive home and you have to mow the lawn… The difference [with being a fighter pilot] is: you never leave the combat zone.

You sit in a reclining chair in an air-conditioned operations room in an air force base in Nevada, yet you never leave the combat zone. Why? Because combat is a state of mind?

The Pentagon always prefers sterile language — language that obscures the reality of war. Yet remote warfare really begs the question as to whether “combat” in which one combatant’s death is near certain while his opponent’s life is in no danger, is really combat at all.

In combat, each side is battling the other. Com- means together — not thousands of miles apart.

Remote extrajudicial execution would be a more accurate description for strikes that in their frequency have become “the cannon fire of this war” — though the Air Force might find it difficult recruiting executioners.

For the military, there appear to be no limits on their effort to promote the value of soldiers who can shoot without ever getting shot and can go overseas without ever leaving home.

We’ve got a predator pilot that hasn’t left the skies of South-West Asia for nine years… This captain has been sitting at Creech Air Force Base [in Nevada] flying over South-West Asia, eight to ten hours a day, five to six days a week, 52 weeks a year for the past nine years… If you want to go and talk to a world expert on Iraq or Afghanistan, maybe you don’t need to go to Iraq and Afghanistan — maybe you need to go talk to that young captain down at Creech, because they’ve been staring at that ground for the past nine years.

Thus we have a picture of the future of the U.S. military’s approach to (not) facing its adversaries: that it can learn all it needs to know through electronic imagery and it kill everyone it needs to kill without shedding a drop of blood or sweat. This will be America’s ignoble and blunt efficiency.

This vision of killing-without-combat resonates with the image of UC Davis police Lt. John Pike as he casually pepper-sprays student demonstrators. In each case the willingness to inflict suffering is directly related to the assailant’s own sense of impunity — his ability to fire without being fired upon.

There is nothing noble or brave in this approach to violence.

In Shakespeare’s Henry V, as the Battle of Agincourt is about to commence, the king addresses his men — “We few, we happy few, we band of brothers” — heavily outnumbered by the French and facing the risk of imminent slaughter.

Henry — a king who fights with his men and doesn’t simply issue commands — declares:

… he which hath no stomach to this fight,

Let him depart; his passport shall be made,

And crowns for convoy put into his purse;

We would not die in that man’s company

That fears his fellowship to die with us.

To the extent that there is a noble dimension to warfare it is this: that those willing to kill are also willing to die. Those taking the lives of others do so knowing that just as easily they could lose their own.

Pakistan demands U.S. vacate suspected drone base

The Associated Press reports: The Pakistani government has demanded the U.S. vacate an air base within 15 days that the CIA is suspected of using for unmanned drones.

The government issued the demand Saturday after NATO helicopters and jet fighters allegedly attacked two Pakistan army posts along the Afghan border, killing 24 Pakistani soldiers.

Islamabad outlined the demand in a statement it sent to reporters following an emergency defense committee meeting chaired by Pakistani Prime Minister Yousuf Raza Gilani.

Shamsi Air Base is in southwestern Baluchistan province. The U.S. is suspected of using the facility in the past to launch armed drones and observation aircraft to keep pressure on Taliban and al-Qaeda militants in Pakistan’s tribal region.

In Pakistan, drones kill the innocent

Clive Stafford Smith writes: Last Friday, I took part in an unusual meeting in Pakistan’s capital, Islamabad.

The meeting had been organized so that Pashtun tribal elders who lived along the Pakistani-Afghan frontier could meet with Westerners for the first time to offer their perspectives on the shadowy drone war being waged by the Central Intelligence Agency in their region. Twenty men came to air their views; some brought their young sons along to experience this rare interaction with Americans. In all, 60 villagers made the journey.

The meeting was organized as a traditional jirga. In Pashtun culture, a jirga acts as both a parliament and a courtroom: it is the time-honored way in which Pashtuns have tried to establish rules and settle differences amicably with those who they feel have wronged them.

On the night before the meeting, we had a dinner, to break the ice. During the meal, I met a boy named Tariq Aziz. He was 16. As we ate, the stern, bearded faces all around me slowly melted into smiles. Tariq smiled much sooner; he was too young to boast much facial hair, and too young to have learned to hate.

The next day, the jirga lasted several hours. I had a translator, but the gist of each man’s speech was clear. American drones would circle their homes all day before unleashing Hellfire missiles, often in the dark hours between midnight and dawn. Death lurked everywhere around them.

When it was my turn to speak, I mentioned the official American position: that these were precision strikes and no innocent civilian had been killed in 15 months. My comment was met with snorts of derision.

I told the elders that the only way to convince the American people of their suffering was to accumulate physical proof that civilians had been killed. Three of the men, at considerable personal risk, had collected the detritus of half a dozen missiles; they had taken 100 pictures of the carnage.

In one instance, they matched missile fragments with a photograph of a dead child, killed in August 2010 during the C.I.A.’s period of supposed infallibility. This made their grievances much more tangible.

Collecting evidence is a dangerous business. The drones are not the only enemy. The Pakistani military has sealed the area off from journalists, so the truth is hard to come by. One man investigating drone strikes that killed civilians was captured by the Taliban and held for 63 days on suspicion of spying for the United States.

At the end of the day, Tariq stepped forward. He volunteered to gather proof if it would help to protect his family from future harm. We told him to think about it some more before moving forward; if he carried a camera he might attract the hostility of the extremists.

But the militants never had the chance to harm him. On Monday, he was killed by a C.I.A. drone strike, along with his 12-year-old cousin, Waheed Khan. The two of them had been dispatched, with Tariq driving, to pick up their aunt and bring her home to the village of Norak, when their short lives were ended by a Hellfire missile.

My mistake had been to see the drone war in Waziristan in terms of abstract legal theory — as a blatantly illegal invasion of Pakistan’s sovereignty, akin to President Richard M. Nixon’s bombing of Cambodia in 1970.

But now, the issue has suddenly become very real and personal. Tariq was a good kid, and courageous. My warm hand recently touched his in friendship; yet, within three days, his would be cold in death, the rigor mortis inflicted by my government.

And Tariq’s extended family, so recently hoping to be our allies for peace, has now been ripped apart by an American missile — most likely making any effort we make at reconciliation futile.

U.S. drone kills 28 in south Somalia

Another attack by a US assassination drone has claimed the lives of at least 28 civilians, while injuring dozens of others in southern Somalia, Press TV reports.

The incident took place in the town of Gilib, 350 kilometers south of Mogadishu, a Press TV correspondent reported on Sunday.

The Washington Post reported on Thursday: The Air Force has been secretly flying Reaper drones on counterterrorism missions from a remote civilian airport in southern Ethiopia as part of a rapidly expanding U.S.-led proxy war against an al-Qaeda affiliate in East Africa, U.S. military officials said.

The Air Force has invested millions of dollars to upgrade an airfield in Arba Minch, Ethiopia, where it has built a small annex to house a fleet of drones that can be equipped with Hellfire missiles and satellite-guided bombs. The Reapers began flying missions earlier this year over neighboring Somalia, where the United States and its allies in the region have been targeting al-Shabab, a militant Islamist group connected to al-Qaeda.

On Friday, the Pentagon said the drones are unarmed and have been used only for surveillance and collecting intelligence, though it would not rule out the possibility that they would be used to launch lethal strikes in the future.

Mindful of the 1993 “Black Hawk Down” debacle in which two U.S. military helicopters were shot down in the Somali capital of Mogadishu and 18 Americans killed, the Obama administration has sought to avoid deploying troops to the country.

As a result, the United States has relied on lethal drone attacks, a burgeoning CIA presence in Mogadishu and small-scale missions carried out by U.S. Special Forces. In addition, the United States has increased its funding for and training of African peacekeeping forces in Somalia that fight al-Shabab.

The Washington Post reported last month that the Obama administration is building a constellation of secret drone bases in the Arabian Peninsula and the Horn of Africa, including one site in Ethiopia. The location of the Ethiopian base and the fact that it became operational this year, however, have not been previously disclosed. Some bases in the region also have been used to carry out operations against the al-Qaeda affiliate in Yemen.

The American way of bombing?

At Open Democracy, Derek Gregory writes: The problems with remote-controlled warfare are legion. The human operator ‘is terribly remote from the consequences of his actions; he is likely to be sitting in an air-conditioned trailer, hundreds of miles from the area of battle.’ He evaluates ‘target signatures’ captured by various sensor systems that ‘no more represent human beings than the tokens in a board-type war game.’

The rise of this new ‘American way of bombing’, as it’s been called, has two particularly serious consequences. First, ‘through its isolation of the military actor from his target, automated warfare diminishes the inhibitions that could formerly be expected on the individual level in the exercise of warfare’. In short, killing is made casual. Secondly, once the risk of combat is transferred to the target, it becomes much easier for the state to go to war. Domestic audiences are disengaged from the violence waged in their name: ‘Remote-controlled warfare reduces the need for the public to confront the consequences of military action abroad.’

All familiar stuff, you might think, except that these warnings were not prompted by the appearance of Predators and Reapers in the skies over Afghanistan, Pakistan, Somalia or Yemen. They appeared in Harper’s Magazine in June 1972, the condensed results of a study of the US air war in Indochina by a group of scholar-activists at Cornell University. As they suggest, crucial elements of today’s ‘drone wars’ were assembled during the US bombing of Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia. There were three of them: drones, real-time visual reconnaissance, and the electronic battlefield.

The US fought multiple air wars in Indochina. The air strikes against North Vietnam involved what is now called deliberate targeting, in which targets are identified and assigned to aircrews before take off. To the US military the first series of attacks from 1965 to 1968 (code-named ‘Rolling Thunder’) was an interdiction campaign to close lines of communication and choke off the supply of men and materials from the North to the insurgency in the South. To President Johnson and his civilian advisers, however, its purpose was to open up a different line of communication: bombing was a way of ‘sending a message’ to Hanoi, designed to coerce the North through a ‘diplomatic orchestration of signals and incentives, of carrots and sticks, of the velvet glove of diplomacy backed by the mailed fist of air power.’ From either perspective the campaign had to be carefully controlled and calibrated, but the air intelligence was of variable quality. Starting in October

1964 the US Air Force sought to improve the situation by using reconnaissance drones, which were launched from C-130A transport aircraft on programmed flight paths over target areas in North Vietnam (and Laos) and then recovered off Da Nang.

American 16-year-old boy — latest victim in Obama’s global drone war

The Washington Post reports: In the days before a CIA drone strike killed al-Qaeda operative Anwar al-Awlaki last month, his 16-year-old son ran away from the family home in Yemen’s capital of Sanaa to try to find him, relatives say. When he, too, was killed in a U.S. airstrike Friday, the Awlaki family decided to speak out for the first time since the attacks.

“To kill a teenager is just unbelievable, really, and they claim that he is an al-Qaeda militant. It’s nonsense,” said Nasser al-Awlaki, a former Yemeni agriculture minister who was Anwar al-Awlaki’s father and the boy’s grandfather, speaking in a phone interview from Sanaa on Monday. “They want to justify his killing, that’s all.”

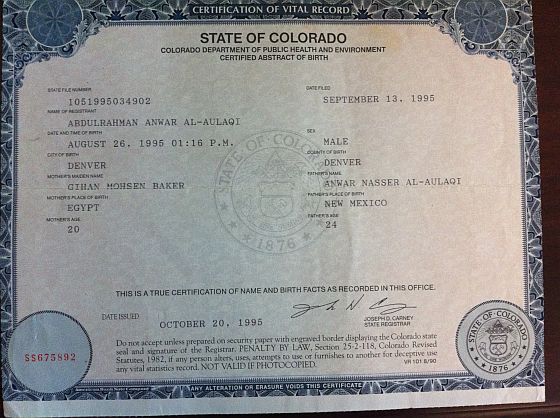

The teenager, Abdulrahman al-Awlaki, a U.S. citizen who was born in Denver in 1995, and his 17-year-old Yemeni cousin were killed in a U.S. military strike that left nine people dead in southeastern Yemen.

The young Awlaki was the third American killed in Yemen in as many weeks. Samir Khan, an al-Qaeda propagandist from North Carolina, died alongside Anwar al-Awlaki.

Yemeni officials said the dead from the strike included Ibrahim al-Banna, the Egyptian media chief for al-Qaeda’s Yemeni affiliate, and also a brother of Fahd al-Quso, a senior al-Qaeda operative who was indicted in New York in the 2000 attack on the USS Cole in the port of Aden.

The strike occurred near the town of Azzan, an Islamist stronghold. The Defense Ministry in Yemen described Banna as one of the “most dangerous operatives” in al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, often referred to by the acronym AQAP.

U.S. officials said they were still assessing the results of the strike Monday evening to determine who was killed. The officials would not discuss the attack in any detail, including who the target was, but typically the CIA and the Pentagon focus on senior figures in al-Qaeda’s affiliate in Yemen.

“We have seen press reports that AQAP senior official Ibrahim al-Banna was killed last Friday in Yemen and that several others, including the son of Anwar al-Awlaki, were with al-Banna at the time,” said Thomas F. Vietor, a spokesman for the National Security Council. “For over the past year, the Department of State has publicly urged U.S. citizens not to travel to Yemen and has encouraged those already in Yemen to leave because of the continuing threat of violence and the presence of terrorist organizations, including AQAP, throughout the country.”

A senior congressional official who is familiar with U.S. operations in Yemen and spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss sensitive policy issues said, “If they knew a 16-year-old was there, I think that would be cause for them to say: ‘Gee, we ought not to hit this guy. That would be considered collateral damage.’ ”

The official said that the CIA and the military’s Joint Special Operations Command are expected to ensure that women and children are not killed in airstrikes in Pakistan and Yemen but that sometimes it might not be possible to distinguish a teenager from militants.

Amy Davidson writes: Here is a birth certificate, for a boy who was born in Denver, Colorado, on September 13, 1995. (Via the Washington Post.) He turned sixteen a month ago, and a few days ago he died, killed when one of his country’s drones hit him and a number of other people in Yemen. His name was Abdulrahman al-Awlaki. His father, Anwar al-Awlaki, who, as the birth certificate notes, was himself born in New Mexico, and was twenty-four years older than his son, was killed a couple of weeks ago, in a separate attack. The father was targeted for assassination. He was an American citizen, and there were no judicial proceedings against him, just, reportedly, a White House legal opinion that concluded that it would be fine to kill him anyway, because the Administration thought he was dangerous. Anwar al-Awlaki was a member of Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula and wrote angry and ugly sermons for them. The Administration says that it had to kill him because he had become “operational,” but so far it has kept the evidence for that to itself.

Was the son targeted, too? The Yemeni government says that another person, a grown man, was the target in the attack that killed Abdulrahman. Maybe he was just in the wrong place, like the Yemeni seventeen-year-old who reportedly died, too. Abdulrahman’s family said that he had been at a barbecue, and told the Post that they were speaking to the paper to answer reports said that Abdulrahman was a fighter in his twenties. Looking at his birth certificate, one wonders what those assertions say either about the the quality of the government’s evidence—or the honesty of its claims—and about our own capacity for self-deception. Where does the Obama Administration see the limits of its right to kill an American citizen without a trial? (The last time I wrote about Awlaki, a reader commented that “Awlaki was a citizen in name only”; but that name is the name of the law, and is, when it comes down to it, all any of us have, unless we want to rely on how charming our government finds us.) And what are the protections for an American child?

You can, in many ways, blame Abdulrahman’s death on his father—for not staying in Colorado, for introducing his son to the wrong people, for being who he was. That would be a fair part of an assessment of Anwar al-Awlaki’s character. But it’s not sufficient. He may have put his child in a bad situation, but we were the ones with the drone. One fault does not preclude another. We have to ask ourselves what we are doing, and at what cost.