The Washington Post reports: The U.S. military has erected a 64,000-square-foot headquarters building on the dusty moonscape of southwestern Afghanistan that comes with all the tools to wage a modern war. A vast operations center with tiered seating. A briefing theater. Spacious offices. Fancy chairs. Powerful air conditioning.

Everything, that is, except troops.

The windowless, two-story structure, which is larger than a football field, was completed this year at a cost of $34 million. But the military has no plans to ever use it. Commanders in the area, who insisted three years ago that they did not need the building, now are in the process of withdrawing forces and see no reason to move into the new facility.

For many senior officers, the unused headquarters has come to symbolize the staggering cost of Pentagon mismanagement: As American troops pack up to return home, U.S.-funded contractors are placing the finishing touches on projects that are no longer required or pulling the plug after investing millions of dollars.

In Kandahar province, the U.S. military recently completed a $45 million facility to repair armored vehicles and other complex pieces of equipment. The space is now being used as a staging ground to sort through equipment that is being shipped out of the country.

In northern Afghanistan, the State Department last year abandoned plans to occupy a large building it had intended to use as a consulate. After spending more than $80 million and signing a 10-year lease, officials determined the facility was too vulnerable to attacks. [Continue reading…]

Category Archives: war in Afghanistan

U.S. considers withdrawing all troops from Afghanistan by end of 2014

The New York Times reports: Increasingly frustrated by his dealings with President Hamid Karzai, President Obama is giving serious consideration to speeding up the withdrawal of United States forces from Afghanistan and to a “zero option” that would leave no American troops there after next year, according to American and European officials.

Mr. Obama is committed to ending America’s military involvement in Afghanistan by the end of 2014, and Obama administration officials have been negotiating with Afghan officials about leaving a small “residual force” behind. But his relationship with Mr. Karzai has been slowly unraveling, and reached a new low after an effort last month by the United States to begin peace talks with the Taliban in Qatar.

Mr. Karzai promptly repudiated the talks and ended negotiations with the United States over the long-term security deal that is needed to keep American forces in Afghanistan after 2014.

A videoconference between Mr. Obama and Mr. Karzai designed to defuse the tensions ended badly, according to both American and Afghan officials with knowledge of it. Mr. Karzai, according to those sources, accused the United States of trying to negotiate a separate peace with both the Taliban and their backers in Pakistan, leaving Afghanistan’s fragile government exposed to its enemies.

Mr. Karzai had made similar accusations in the past. But those comments were delivered to Afghans — not to Mr. Obama, who responded by pointing out the American lives that have been lost propping up Mr. Karzai’s government, the officials said.

The option of leaving no troops in Afghanistan after 2014 was gaining momentum before the June 27 video conference, according to the officials. But since then, the idea of a complete military exit similar to the American military pullout from Iraq has gone from being considered the worst-case scenario — and a useful negotiating tool with Mr. Karzai — to an alternative under serious consideration in Washington and Kabul. [Continue reading…]

Video: Talking to the Taliban

Taliban step toward Afghan peace talks is hailed by U.S.

The New York Times reports: The Taliban signaled a breakthrough in efforts to start Afghan peace negotiations on Tuesday, announcing the opening of a political office in Qatar and a new readiness to talk with American and Afghan officials, who said in turn that they would travel to meet insurgent negotiators there within days.

If the talks begin, they will be a significant step in peace efforts that have been locked in an impasse for nearly 18 months, after the Taliban walked out and accused the United States of negotiating in bad faith. American officials have long pushed for such talks, believing them crucial to stabilizing Afghanistan after the 2014 Western military withdrawal.

But the Taliban may have other goals in moving ahead. Their language made clear that they sought to be dealt with as a legitimate political force with a long-term role to play beyond the insurgency. In that sense, in addition to aiding in talks, the actual opening of their office in Qatar — nearly a year and a half after initial plans to open it were announced and then soon after suspended — could be seen as a signal that the Taliban’s ultimate aim is recognition as an alternative to the Western-backed government of President Hamid Karzai.

By agreeing to negotiations, the Taliban can “come out in the open, engage the rest of the region as legitimate actors, and it will be very difficult to prevent that when we recognize the office and are talking to the office,” said Vali Nasr, a former State Department official who is the dean of the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies.

The United States, already heading toward its military exit, has little to offer beyond prisoner exchanges, and the Taliban are “not trying to help our strategy,” Mr. Nasr warned. “They’re basically trying to put in place their own strategy.”

The Taliban overture coincided with an important symbolic moment in the American withdrawal: the formal announcement on Tuesday of a complete security handover from American troops to Afghan forces across the country. That shift had already become obvious in recent months as the Afghan forces had tangibly taken the lead — and as the Taliban had responded by increasing the tempo of attacks against them.

Yet since at least 2009, even top American generals maintained that a permanent peace could not be won on the battlefield, and American diplomats have engaged in nearly three years of holding secret meetings and working through diplomatic back channels to lay the groundwork for talks to begin. [Continue reading…]

Video: Afghanistan drawdown

How do you ask a jihadist to be the last jihadist to die in Afghanistan?

Sami Yousafzai and Ron Moreau report: As the spring weather warms and the snow melts off the high mountain passes separating Pakistan and Afghanistan, hundreds of Taliban fighters who spent the winter in Afghan refugee camps and other safe havens inside Pakistan are preparing to return to battle. But this year some insurgents are having second thoughts about fighting in Afghanistan at a time when it appears that peace talks between the US and the Taliban are about to resume in Qatar after a year’s hiatus.

Indeed, there are heated debates raging among the fighters as to the wisdom of returning to fight and perhaps die as peace prospects are being discussed. “The leadership hopes to dispatch a big number of fighters to Afghanistan this year,” says Zabihullah, a senior Taliban operative whose information has proved reliable in the past. “But now there is great confusion among the fighters whether to go and fight or stay behind in Pakistan and await the results of the Qatar peace talks.”

In a mosque made of mud-bricks in the middle of the Haripur Afghan refugee camp, some 40 miles north of Islamabad, five Taliban fighters are relaxing, enjoying the warm spring weather, and sipping green tea from discolored tea cups. “Take advantage of the rest and the sunshine because in less than one month we have to return to the jihad,” says Mullah Mohammad Khan, 30, the senior fighter among the group. But his comrade-in-arms, Mohidain Akhund, does not share Khan’s enthusiasm. “This year my heart really does not want to go back to the jihad,” Akhund tells Khan frankly. “Our leaders are talking to the kafirs in Qatar and then asking us to return to Afghanistan to resist the Americans. Allah, pardon me, but I cannot make up my mind whether or not to go to the jihad this year.”

Khan, a sub-commander from northern Baghlan province, tries to argue with Akhund, warning him that he’s in danger of losing his faith. “These are satanic temptations,” he says. “If you say no to the jihad then how will you answer to Allah on Judgment Day?” Akhund is still not convinced. “I am proud to have been in the jihad for the past five years in Helmand [Province] and to have lost a brother and a nephew,” he tells Khan. “But how can I continue fighting when our leaders are enjoying the Americans’ hospitality in Qatar and we’re told we have to kill Afghan soldiers?” Another fighter named Abdullah pipes up, agreeing with Akhund, saying he is also confused about what to do this year. “Our leaders are enjoying air conditioned rooms, driving luxury cars and living in good houses while we live a troubled life fighting in Afghanistan,” says Abdullah. Khan still tries to cajole them. “We do not perform jihad for this or that personality,” he says. “We offer our sweet breath for Allah and we should expect rewards from Allah, not the leaders who are human and far from perfect.” [Continue reading…]

Afghanistan: The way to peace

Anatol Lieven writes: A very strange idea has spread in the Western media concerning Afghanistan: that the US military is withdrawing from the country next year, and that the present Afghan war has therefore entered into an “endgame.” The use of these phrases reflects a degree of unconscious wishful thinking that amounts to collective self-delusion.

In fact, according a treaty signed by the United States and the Karzai administration, US military bases, aircraft, special forces, and advisers will remain in Afghanistan at least until the treaty expires in 2024. These US forces will be tasked with targeting remaining elements of al-Qaeda and other international terrorist groups operating from Afghanistan and Pakistan; but equally importantly, they will be there to prop up the existing Afghan state against overthrow by the Taliban. The advisers will continue to train the Afghan security forces. So whatever happens in Afghanistan after next year, the United States military will be in the middle of it—unless of course it is forced to evacuate in a hurry.

As to the use of the word “endgame,” this might be appropriate if next year, upon the departure of US ground forces, the entire Afghan population, overcome with sorrow at the loss of their beloved allies, rolls over and dies on the spot. The struggle for power in Afghanistan will not “end” and US policymakers should not, as in the past, hop away from a swamp they’ve done much to create.

Two major new books, together with a number of lesser works, are crucial to an understanding of Afghanistan, the flaws of the Western project there, the enemies that we are facing, and therefore of possible future policies. Barnett Rubin, senior adviser to the US special representative for Pakistan and Afghanistan in the first Obama term, has been consistently among the wisest and most sensible of US expert voices on Afghanistan. His book Afghanistan from the Cold War Through the War on Terror is a compilation of his essays and briefing papers over the years, framed by passages looking back at the sweep of Afghan history and the US involvement there since 1979.

Peter Bergen is a former journalist and long-standing commentator and writer on the region now working at the New America Foundation in Washington, D.C.1 He has edited and introduces Talibanistan, a frequently brilliant collection of essays by different experts on the Taliban in Afghanistan and Pakistan, including an analysis of the extent to which their past links with al-Qaeda represent an enduring threat to the West, and of how far a peace settlement with them may be possible. Rubin’s and Bergen’s works should be read in conjunction with a fascinatingly detailed new book by Vahid Brown and Don Rassler on the Haqqani network, the insurgent group led by Mawlawi Jalaluddin Haqqani and his son, which operates on both sides of the Afghan–Pakistani border. Its title, Fountainhead of Jihad, is the name of a magazine published by the Haqqanis. [Continue reading…]

Video: U.S. special destabilizing forces in Afghanistan

A photographer’s return to Afghanistan after losing three limbs

A year ago, Giles Duley gave this TED talk:

In a magazine feature article for the New York Times published last May, Luke Mogelson described the medical care provided by Emergency, an Italian-based nonprofit that opened its first surgical center in Afghanistan in 1999. He also described the ‘criminal’ discharge policies being applied to Afghans who get treated at NATO hospitals.

In April, I traveled to Sayad, a town in Kapisa Province, to meet a 14-year-old boy named Zobair, who had recently been discharged from a hospital at Bagram Air Base, one of the largest American military installations in Afghanistan. Zobair’s uncle Nasir had taken him to Sayad in a borrowed Toyota hatchback, its rear seats folded forward to accommodate the green U.S. Army litter on which Zobair reclined. We were parked on the bank of a wide river with small wooden platforms extending over the water’s edge, where you could order lunch from local fishmongers. My interpreter and I arrived early and bought food for Zobair and Nasir — a gesture that felt ridiculous now, in light of Zobair’s condition.

Both of his legs were gone, and wounds covered his hands, arms and back. He was nauseated and fevered; every movement elicited a grimace. “Most of the pain is in my stomach,” Zobair told me as soon as we met. His eyes were half-shut, heavy with fatigue, and he spoke so softly that I had to lean close to catch his words. Without a wheelchair, Zobair had no way to reach the landing where we had set up the meal. When Nasir climbed into the back of the Toyota and raised Zobair’s shalwar kameez, he revealed a pouching system attached to a stoma and four pink tubes sticking out of Zobair’s sides. Fifty-two metal staples held together an incision running the length of his abdomen.

Zobair and Nasir were from Tagab District, where French troops have struggled for years to dislodge a deeply entrenched insurgency, without much success. In February, a French airstrike, mistaking them for insurgents, killed seven boys while they were herding sheep not far from Tagab. A few weeks later, according to Zobair and his family, Zobair was sitting outside his house with four cousins, watching the sun go down, when two low-flying helicopters approached from the distance. Helicopters have long been a daily occurrence in Tagab, but something about the way this pair hovered near the house made Zobair nervous. He said as much to his cousins, who mocked him for being overanxious.

Zobair stood up and began to walk away. He does not know what kind of ordnance or ammunition the helicopter fired. Given the damage, it was likely a Hellfire missile. Two cousins — ages 14 and 18 — were killed immediately. Zobair, who had taken about four steps before the explosion, was thrown into an irrigation ditch. Villagers rushed the survivors to the French military base in Tagab, where another of Zobair’s cousins soon died. In response to my questions about the helicopter strike, a representative for the French military told me that they had conducted an investigation, the conclusions of which were “full positive”: “On that day, after having checked there were no civilians in the area, one helicopter fired at a group of five insurgents with hostile intentions.”

The last thing Zobair remembers before losing consciousness was a foreigner sticking him with a needle. He woke up “in a white room with white walls,” he told me. “They wouldn’t tell us where we were.” Back in Tagab, no one from the base would inform Nasir where Zobair had been taken; it was generally known, however, that casualties from Kapisa were often airlifted to Bagram. “We came to Bagram several times to write our names and give them to the interpreter at the gate,” Nasir said. “Sometimes the interpreter told us, ‘Yes, he is here.’ Sometimes he told us, ‘No, he is not here.’ Zobair called us one time. He told us: ‘I am in a hospital, but I don’t know where. I’m not allowed to tell.’ ” When I asked NATO why Zobair was not allowed to speak with his family, a representative replied, “We know there is a policy on this and are seeking more information at this time.” I was later told that he should have been allowed to call home.

After 23 days, Nasir received a call from an interpreter at Bagram, who told him to come pick up his nephew. At the airfield, Zobair was carried out from the hospital and put into the ambulance, accompanied by an Afghan interpreter. The interpreter told Nasir that they should go to the Red Cross in Kabul so that Zobair’s amputated legs could be fitted for prostheses. She then handed Nasir some papers detailing, in English, the treatment that Zobair received.

If Nasir had been able to read the papers, he would have learned that American surgeons at Craig Joint Theater Hospital saved Zobair’s life with a battery of sophisticated procedures. The incision on Zobair’s abdomen was from a laparotomy that enabled the doctors to repair his lacerated spleen, colon and kidney; the pouching system was to collect feces from an ileostomy, where a section of damaged intestine had been removed; and the four tubes sticking out of his sides were internal compression sutures helping to hold his abdomen together. Curiously, the only future treatment recommended for Zobair was to “follow up with a surgeon in six months to have the ileostomy takedown” — that is, to have the intestine reattached and the temporary pouching system removed. According to Nasir, he was not given any guidance about what to do for the internal sutures and 52 metal staples, though both were meant to remain in place no longer than a week or two, after which they posed a risk of becoming infected. Continue reading

Afghanistan accuses U.S. Special Operations troops of murder, abduction, and torture

The New York Times reports: The Afghan government barred elite American forces from operating in a strategic province adjoining Kabul on Sunday, citing complaints that Afghans working for American Special Operations forces had tortured and killed villagers in the area.

The ban was scheduled to take effect in two weeks in the province, Maidan Wardak, which is seen as a crucial area in defending the capital against the Taliban. If enforced, it would effectively exclude the American military’s main source of offensive firepower from the area, which lies southwest of Kabul and is used by the Taliban as a staging ground for attacks on the city.

By announcing the ban, the government signaled its willingness to take a far harder line against abuses linked to foreign troops than it has in the past. The action also reflected a deep distrust of international forces that is now widespread in Afghanistan, and the view held by many Afghans, President Hamid Karzai among them, that the coalition shares responsibility with the Taliban for the violence that continues to afflict the country.

Coalition officials said they were talking to their Afghan counterparts to clarify the ban and the allegations that prompted it. They declined to comment further.

Afghan officials said the measure was taken as a last resort. They said they had tried for weeks to get the coalition to cooperate with an investigation into claims that civilians had been killed, abducted or tortured by Afghans working for American Special Operations forces in Maidan Wardak. But the coalition was not responsive, they said. [Continue reading…]

British PM invites Taliban to talks over Afghanistan’s future

The Guardian reports: David Cameron issued a direct appeal to the Taliban to enter peaceful talks on the future of Afghanistan after hosting talks at Chequers with the Afghan president, Hamid Karzai, and Pakistan’s president, Asif Ali Zardari.

The prime minister said the two leaders had agreed “an unprecedented level of co-operation”.

He said they had agreed to sign up to a strategic partnership between their two countries in the autumn.

At the same time, they also agreed to the opening of an office in the Qatari capital, Doha, for negotiations between the Taliban and the Afghan high peace council.

Cameron said the agreement should send a clear message to the Taliban. “Now is the time for everyone to participate in a peaceful, political process in Afghanistan,” he said.

He added: “This should lead to a future where all Afghans can participate peacefully in that country’s political process.”

Karzai said that they had had a “very frank and open discussion” and echoed Cameron’s appeal to the Taliban to join peace talks. [Continue reading…]

Ann Jones: The Afghan end game?

The euphemisms will come fast and furious. Our soldiers will be greeted as “heroes” who, as in Iraq, left with their “heads held high,” and if in 2014 or 2015 or even 2019, the last of them, as also in Iraq, slip away in the dark of night after lying to their Afghan “allies” about their plans, few here will notice.

This will be the nature of the great Afghan drawdown. The words “retreat,” “loss,” “defeat,” “disaster,” and their siblings and cousins won’t be allowed on the premises. But make no mistake, the country that, only years ago, liked to call itself the globe’s “sole superpower” or even “hyperpower,” whose leaders dreamed of a Pax Americana across the Greater Middle East, if not the rest of the globe is… not to put too fine a point on it, packing its bags, throwing in the towel, quietly admitting — in actions, if not in words — to mission unaccomplished, and heading if not exactly home, at least boot by boot off the Eurasian landmass.

Washington has, in a word, had enough. Too much, in fact. It’s lost its appetite for invasions and occupations of Eurasia, though special operations raids, drone wars, and cyberwars still look deceptively cheap and easy as a means to control… well, whatever. As a result, the Afghan drawdown of 2013-2014, that implicit acknowledgement of yet another lost war, should set the curtain falling on the American Century as we’ve known it. It should be recognized as a landmark, the moment in history when the sun truly began to set on a great empire. Here in the United States, though, one thing is just about guaranteed: not many are going to be paying the slightest attention.

No one even thinks to ask the question: In the mighty battle lost, who exactly beat us? Where exactly is the triumphant enemy? Perhaps we should be relieved that the question is not being raised, because it’s a hard one to answer. Could it really have been the scattered jihadis of al-Qaeda and its wannabes? Or the various modestly armed Sunni and Shiite minority insurgencies in Iraq, or their Pashtun equivalents in Afghanistan with their suicide bombers and low-tech roadside bombs? Or was it something more basic, something having to do with a planet no longer amenable to imperial expeditions? Did the local and global body politic simply and mysteriously spit us out as the distasteful thing we had become? Or is it even possible, as Pogo once suggested, that in those distant, unwelcoming lands, we met the enemy and he was us? Did we in some bizarre fashion fight ourselves and lose? After all, last year, more American servicemen died from suicide than on the battlefield in Afghanistan; and a startling number of Americans were killed in “green on blue” or “insider” attacks by Afghan “allies” rather than by that fragmented movement we still call the Taliban.

Whoever or whatever was responsible, our Afghan disaster was remarkably foreseeable. In fact, anyone who, from 2006 on, read Ann Jones’s Afghan reports at TomDispatch wouldn’t have had a doubt about the outcome of the war. Her first piece, after all, was prophetically entitled “Why It’s Not Working in Afghanistan.” (“The answer is a threefold failure: no peace, no democracy, and no reconstruction.”) From Western private-contractors-cum-looters making a figurative killing off the “reconstruction” of the country to an Afghan army that was largely a figment of the American imagination to up-armored U.S. soldiers on well-guarded bases whose high-tech equipment and comforts of home blinded them to the nature of the enemy, hers has long been a tale of impending failure. Now, that war seems headed for its predictable end, not for the Afghans who, as Jones indicates in her latest sweeping report from Kabul, may face terrible years ahead, but for the U.S. After more than 11 years, the war that is often labeled the longest in American history is slowly winding down and that’s no small thing.

So leave the mystery of who beat us to the historians, but mark the moment. It’s historic. Tom Engelhardt

Counting down to 2014 in Afghanistan

Three lousy options: pick one

By Ann JonesKabul, Afghanistan — Compromise, conflict, or collapse: ask an Afghan what to expect in 2014 and you’re likely to get a scenario that falls under one of those three headings. 2014, of course, is the year of the double whammy in Afghanistan: the next presidential election coupled with the departure of most American and other foreign forces. Many Afghans fear a turn for the worse, while others are no less afraid that everything will stay the same. Some even think things will get better when the occupying forces leave. Most predict a more conservative climate, but everyone is quick to say that it’s anybody’s guess.

Only one thing is certain in 2014: it will be a year of American military defeat. For more than a decade, U.S. forces have fought many types of wars in Afghanistan, from a low-footprint invasion, to multiple surges, to a flirtation with Vietnam-style counterinsurgency, to a ramped-up, gloves-off air war. And yet, despite all the experiments in styles of war-making, the American military and its coalition partners have ended up in the same place: stalemate, which in a battle with guerrillas means defeat. For years, a modest-sized, generally unpopular, ragtag set of insurgents has fought the planet’s most heavily armed, technologically advanced military to a standstill, leaving the country shaken and its citizens anxiously imagining the outcome of unpalatable scenarios.

Prince Harry branded a ‘coward’ by Taliban

The Telegraph reports: Taliban commanders have branded Prince Harry a naïve “coward” for his comments comparing the decade-long conflict in Afghanistan with computer games.

Two senior figures told The Daily Telegraph that the unguarded description was an insult to the men who had fought and died alongside Captain Wales.

They were angered by the way Prince Harry described his role as co-pilot of an Apache helicopter, in charge of its weapons systems, firing Hellfire air-to-surface missiles, rockets and a 30-millimetre gun.

“It’s a joy for me because I’m one of those people who loves playing PlayStation and Xbox, so with my thumbs I like to think I’m probably quite useful,” he said in an interview timed to coincide with his departure after a 20-week tour.

The unguarded comments could prove a headache for President Hamid Karzai, who has staked his reputation on working closely with Nato-led forces and wants the US to station troops in Afghanistan beyond the end of 2014.

It also hands insurgents a propaganda opportunity as they continue to try to turn the local population against foreign fighters in a war that is becoming as much about PR salvoes as it is about rockets and bullets.

A decade of western folly has erased hope from Afghanistan

Jonathan Steele writes: Clouds of uncertainty and foreboding hang over Kabul as heavily as the traffic pollution, which obscures its once stunning vista of surrounding mountains. Eleven years after the west’s military intervention, the withdrawal of US, British and other international forces has started, but no one knows whether their departure will lead to more or less instability for a country that has been mired in civil war for almost 40 years.

Most Afghans say they are happy to see foreign troops depart, yet many are also concerned at the vacuum they will leave, in spite of international pledges of billions of dollars for the next decade. In seven visits to the country since the Taliban were toppled I have never found the Afghan mood so febrile and gloomy.

Disappointment and bitterness are widespread. Long gone are the high hopes sparked by regime change in 2001. The foreigners delivered far less than they promised. Kabul was transformed into a canyon of concrete blast walls and watchtowers shielding enclaves from which foreign diplomats only emerge in armoured vehicles for official contacts. Journalists, NGO staff and independent westerners who have lived here for years sense a rising mood of anger, and most have stopped going around Kabul on foot for fear of hostile looks, insults hissed in Dari or Pashto, or stones being thrown.

While Afghans blame government officials for creaming off much of the aid money, they blame western donors for doing too little to reduce corruption. US military commanders who handed out cash for “quick impact” projects are accused of encouraging it. [Continue reading…]

Afghanistan seeks India’s help as West pullout nears

Reuters reports: India will step up training of the Afghan police and military after a request on Monday by President Hamid Karzai, who also urged Indian businesses to invest in his battle-weary nation as it gears up for the departure of NATO troops.

The extra help is likely to be welcomed by the United States, which sees India as a stabilizing power in South Asia. But it may unnerve Pakistan, which frets about losing influence in neighboring Afghanistan.

“We do want to expand that as required and wished by Afghanistan. We will respond,” said India’s Foreign Minister Salman Khurshid when asked about the security program following a lecture given by the Afghan president in New Delhi.

In June, U.S. Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta called on India to do more to support both the Afghan economy and security forces as Western nations prepare to end their combat missions there in 2014.

Al Jazeera reports: The European Union has announced that it is suspending $25million in aid for Afghanistan, warning that aid will be increasingly conditional on the government sticking to agreed reforms.

Payment of the $25 million aimed at reforming the justice system was deferred because of a lack of progress on the issue, EU ambassador Vygaudas Usackas said on Monday.

Usackas was speaking at the signing of a $76 million financing agreement on “efficient and effective governance” and “justice for all” with Afghan Finance Minister Omar Zakhiwal.

“If the European Union is deeply committed in supporting Afghanistan, it needs to stress that in the spirit of the Tokyo agreement, support will be increasingly conditional of the delivery of the Afghan government on the agreed reform agenda,” Usackas said.

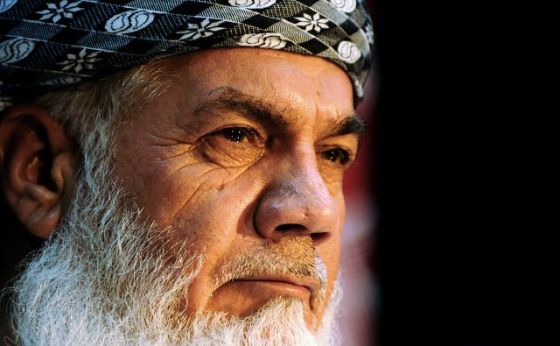

Ismail Khan

Meanwhile, the New York Times reports: One of the most powerful mujahedeen commanders in Afghanistan, Ismail Khan, is calling on his followers to reorganize and defend the country against the Taliban as Western militaries withdraw, in a public demonstration of faltering confidence in the national government and the Western-built Afghan National Army.

Mr. Khan is one of the strongest of a group of warlords who defined the country’s recent history in battling the Soviets, the Taliban and one another, and who then were brought into President Hamid Karzai’s cabinet as a symbol of unity. Now, in announcing that he is remobilizing his forces, Mr. Khan has rankled Afghan officials and stoked fears that other regional and factional leaders will follow suit and rearm, weakening support for the government and increasing the likelihood of civil war.

This month, Mr. Khan rallied thousands of his supporters in the desert outside Herat, the cultured western provincial capital and the center of his power base, urging them to coordinate and reactivate their networks. And he has begun enlisting new recruits and organizing district command structures.

“We are responsible for maintaining security in our country and not letting Afghanistan be destroyed again,” Mr. Khan, the minister of energy and water, said at a news conference over the weekend at his office in Kabul. But after facing criticism, he took care not to frame his action as defying the government: “There are parts of the country where the government forces cannot operate, and in such areas the locals should step forward, take arms and defend the country.”

President Karzai and his aides, however, were not greeting it as an altruistic gesture. The governor of Herat Province called Mr. Khan’s reorganization an illegal challenge to the national security forces. And Mr. Karzai’s spokesman, Aimal Faizi, tersely criticized Mr. Khan.

“The remarks by Ismail Khan do not reflect the policies of the Afghan government,” Mr. Faizi said. “The government of Afghanistan and the Afghan people do not want any irresponsible armed grouping outside the legitimate security forces structures.”

In Kabul, Mr. Khan’s provocative actions have played out in the news media and brought a fierce reaction from some members of Parliament, who said the warlords were preparing to take advantage of the American troop withdrawal set for 2014.

“People like Ismail Khan smell blood,” Belqis Roshan, a senator from Farah Province, said in an interview. “They think that as soon as foreign forces leave Afghanistan, once again they will get the chance to start a civil war, and achieve their ominous goals of getting rich and terminating their local rivals.”

Indeed, Mr. Khan’s is not the only voice calling for a renewed alliance of the mujahedeen against the Taliban, and some of the others are just as familiar. [Continue reading…]

In Afghan war, enter Sir Mortimer Durand

Myra MacDonald writes: When the British decided to define the outer limits of their Indian empire, they fudged the question. After two disastrous wars in Afghanistan, they sent the Foreign Secretary of India, Sir Mortimer Durand, to Kabul in 1893 to agree the limits of British and Afghan influence. The result was the Durand Line which Pakistan considers today as its border and Afghanistan refuses to recognise. Then, rather than extend the rule of the Raj out to the Durand Line, the British baulked at pacifying the tribes in what is now Pakistan’s Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA). Instead, they used the still-extant Frontier Crimes Regulation of 1901 to keep them at bay, if necessary through collective punishment. The Pashtun tribes living on either side of the Durand Line continued to move back and forth, resenting outside interference and rejecting an arbitrary division of their lands by a foreign power.

The situation remains as nebulous to this day. Pakistan, like the British Raj before it, wants a secure western frontier and has been ready to back Islamist militants in Afghanistan to obtain it. Indeed, its emphasis on Islam has been used as a means of countering ethnic Pashtun nationalism, lest the Pashtun lay claim to a Pashtunistan covering both sides of the Durand Line. Meanwhile, remembering the days when Peshawar was a fabled Afghan city, some Afghans hanker after a Greater Afghanistan, incorporating the lands of all Pashtun (or Afghan) tribes as far as the Indus river. (Historically, the identification of Afghanistan with the Pashtun was such that the words “Afghan” and “Pashtun” were treated as synonyms.) And even those Afghans who recognise how unrealistic it would be to claim a sizeable chunk of modern-day Pakistan retain a proprietary sense over the Pashtun living on the other side of the Durand Line. Meanwhile the Pashtun themselves resent their arbitrary separation between two countries, which has reduced their capacity to exercise political power.

Is the U.S. admitting defeat in Afghanistan?

Tony Karon writes: Don’t expect to hear about it in the presidential campaign debates, but the U.S. will leave Afghanistan locked in an escalating civil war when it observes the 2014 deadline for withdrawing combat troops set by the Obama Administration — and supported by Gov. Mitt Romney. The New York Times reported Tuesday that the U.S. military has had to give up on hopes of inflicting enough pain on the Taliban to set favorable terms for a political settlement. Instead, it will be left up to the Afghan combatants to find their own political solution once the U.S. and its allies take themselves out of the fight.

Washington has known for years that it had no hope of destroying the Taliban, and that it would have to settle for a compromise political solution with an indigenous insurgency that remains sufficiently popular to have survived the longest U.S. military campaign in history. Still, as late as 2009, the U.S. had hoped to set the terms of that compromise, and force the Taliban to find a place for themselves in the constitutional order created by the NATO invasion and accept a Karzai government it has long dismissed as “puppets.” This was the logic behind President Obama’s “surge,” which sent an additional 30,000 U.S. troops into the Taliban’s heartland, with the express purpose of bloodying the insurgents to the point that their leaders would sue for peace on Washington’s terms. But the surge ended last month with the Taliban less inclined than ever to accept U.S. terms as the 2014 departure date for U.S. forces looms.

Now, according to the Times, the best case scenario has been reduced to on in which, as a result of NATO’s training and armaments, “the Taliban find the Afghan Army a more formidable adversary than they expect and [will] be compelled, in the years after NATO withdraws, to come to terms with what they now dismiss as a ‘puppet’ government.” Some would see that as another in a long line of optimistic assessments. The Afghan security forces, or at least its ethnic Tajik core, may well find the political will to fight the Pashtun-dominated Taliban, and the means to prevent themselves from being overrun. But it’s a safe bet that the security forces will control considerably less Afghan territory than NATO forces currently do. [Continue reading…]

U.S. edges towards Soviet model for withdrawal from Afghanistan

The New York Times reports: With the surge of American troops over and the Taliban still a potent threat, American generals and civilian officials acknowledge that they have all but written off what was once one of the cornerstones of their strategy to end the war here: battering the Taliban into a peace deal.

The once ambitious American plans for ending the war are now being replaced by the far more modest goal of setting the stage for the Afghans to work out a deal among themselves in the years after most Western forces depart, and to ensure Pakistan is on board with any eventual settlement. Military and diplomatic officials here and in Washington said that despite attempts to engage directly with Taliban leaders this year, they now expect that any significant progress will come only after 2014, once the bulk of NATO troops have left.

“I don’t see it happening in the next couple years,” said a senior coalition officer. He and a number of other officials spoke on the condition of anonymity because of the delicacy of the effort to open talks.

“It’s a very resilient enemy, and I’m not going to tell you it’s not,” the officer said. “It will be a constant battle, and it will be for years.”

The failure to broker meaningful talks with the Taliban underscores the fragility of the gains claimed during the surge of American troops ordered by President Obama in 2009. The 30,000 extra troops won back territory held by the Taliban, but by nearly all estimates failed to deal a crippling blow.

Critics of the Obama administration say the United States also weakened its own hand by agreeing to the 2014 deadline for its own involvement in combat operations, voluntarily ceding the prize the Taliban has been seeking for over a decade. The Obama administration defends the deadline as crucial to persuading the Afghan government and military to assume full responsibility for the country, and politically necessary for Americans weary of what has already become the country’s longest war. [Continue reading…]