By Anjali Kamat and Ahmad Shokr, Economic and Political Weekly, March 19, 2011

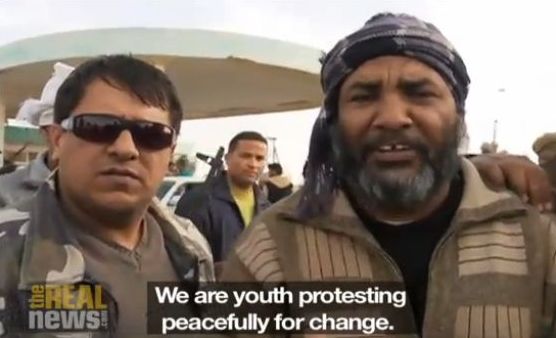

A month into the Libyan revolution, it is easy to forget that what is now an armed rebellion led by a council seeking international recognition began – much like the protests in Tunisia, Egypt, and Yemen – as a peaceful and leaderless popular uprising. Its primary demands were – and to a large extent remain – almost identical to those articulated by demonstrators in other parts of north Africa and west Asia: freedom of expression, democracy, and the ousting of a dictator and his repressive security apparatus. These are fundamentally liberal demands, but when made in a quasi-fascist police state like that ruled by colonel Muammar Gaddafi for nearly 42 years, they acquire a much more radical hue.

The transformation from street protests to armed revolt happened quickly, certainly faster than anyone in Libya could have imagined. After just four days of demonstrations and violent clashes, the long neglected cities of eastern Libya shook off four decades of Gaddafi’s iron-fisted rule. One by one, Benghazi, Al-Bayda, Derna, and Tubruk, all declared their liberation. Almost immediately, protestors established city councils made up of prominent residents and organised popular committees of young men to direct traffic and guard against looting. Even as state-controlled media continued to describe them as treacherous elements implementing a wide range of foreign agendas (western, Egyptian, Tunisian, and Al Qaida), groups of people in Benghazi set up independent newspapers and a handful of former state radio employees took over the local airwaves, broadcasting news about the overnight rebellion and urging everyone to join what came to be known as the “17 February revolution”.

Libya’s revolutionaries are largely middleclass professionals who were suddenly thrust into the leadership of a popular rebellion. They do not represent any single ideological position, but what they do share is a lack of experience with governance or popular mobilisation. This is not surprising given that one of the key achievements of Gaddafi’s four decades in power has been the systematic annihilation of civil society. Any effort towards community or labour organisation or building political associations was swiftly and brutally stamped out as an unacceptable form of dissent, punishable, in some cases, by death. Professional associations that existed were tightly controlled by the state. Notwithstanding his son Saif alIslam’s much-touted PhD dissertation at the London School of Economics on the role of civil society in democratisation, Gaddafi famously said in a televised address last year that civil society is a bourgeois invention of the west with no place in Libya. Labour unions, he added, are for the weak.

A rare exception in this otherwise bleak scenario was the Benghazi Bar Association whose members had been agitating in recent years for relatively minor legal reforms. Their main goal was to oust the former association head, a Gaddafi loyalist who stayed on well past his legally-mandated term. In early February, nervous about the wave of popular uprisings sweeping the Arab world, Gaddafi himself met with the Benghazi lawyers to discuss the standoff. He tried to placate them with promises of reform, and the head of the bar association was dismissed one week before the uprising. But coming on the heels of the dramatic events in Tunisia and Egypt, it was too little, too late.

A Variegated Group

Lawyers, more than any other group, were instrumental in paving the way for the Libyan uprising and several prominent members of the Benghazi Bar Association are now part of Libya’s rebel organisation, the National Transitional Council. Among them are outspoken human rights advocates like Fathy Terbil and Abdel Hafiz Ghogha, who is now the spokesperson of the National Transitional Council. Terbil represented the victims of one of the Gaddafi regime’s most notorious crimes, the mass killing of at least 1,200 inmates of the Abu Salim prison in 1996. When Libyan youth issued a call over Facebook for a “Day of Rage” against the regime on 17 February, the Abu Salim families were among the first to join.

Most of the other figures on the 31-member council have, in the past, publicly questioned Gaddafi’s policies and the terror of his revolutionary committees – and, in some cases, paid for their dissent with long prison terms. Ahmed Zubeir Sanusi, a descendant of Idriss Sanusi, the monarch Gaddafi deposed in 1969, spent 31 years in prison. He is now the council member in charge of political prisoners. Also on the council, in charge of military affairs, is Omar Hariri, who was a young officer who took part in Gaddafi’s coup against Idriss. But since his foiled attempt to overthrow Gaddafi in 1975, Hariri has either been in prison or under house arrest.

A handful of council members held posts in the Gaddafi regime before publicly quitting over the excessive use of force against peaceful demonstrators. The head of the council is the former justice minister, Mustafa Abdel Jalil. During his tenure as a judge and then justice minister since 2007, human rights observers noted that Jalil was unusual in his consistent criticism of the regime’s security forces. The two men on the council responsible for foreign affairs come from pro-business backgrounds. Ali Issawi, who was most recently Libya’s ambassador to India, was minister for economy, trade and investment before that, and holds a doctorate in privatisation. Mahmood Jibril, widely regarded as a reformist, was recently appointed to head the country’s National Planning Council and National Economic Development. He is described in a leaked US diplomatic cable as “a serious interlocutor who gets the US perspective”.

The newly formed council is still grappling with the reality that what began as a hopeful pro-democracy uprising has transformed into a war that they might very well lose. Few among the rebel leadership have military experience. While the rebel army has some defectors from Gaddafi’s forces, it is largely composed of untrained young volunteers who remain bitterly aware that they are in for a long and bloody fight against a far better equipped opponent. As the casualties rise in the besieged towns of the west as well as the frontline towns in the east, some estimates place the numbers of the dead in the thousands.

When asked about the kind of Libyan society they seek to build, members of the National Transitional Council espouse ideals of freedom, human rights, and democracy that some of them have spent years defending. But they have no illusions that translating these ideals into practice will be an easy task. In the current moment, the council does not seem poised – nor does it have a mandate – to formulate a long-term political vision for the country. Its priority, at present, is to gain official recognition from the international community as the legitimate representative of the Libyan people and to bring Gaddafi’s intransigent regime to an end.

No-Fly Zone

One of the council’s immediate, although more controversial, demands is for a no-fly zone over Libya. Council members know full well that a no-fly zone would not necessarily clinch the battle in their favour and could well backfire. Like the courageous protestors in other parts of the region, Libyans want their victory to be their own, achieved without outside help. Everywhere in the east, large banners oppose foreign military intervention. But as the death toll rises, the Libyan’s call for a no-fly zone is a desperate attempt to buy some time.

The anti-imperialist arguments against imposing a no-fly zone are many and convincing. Neutralising Gaddafi’s air power may not give the rebels a much-desired strategic advantage over his ground forces, which are better trained and equipped. Moreover, the decision by foreign powers to impose a no-fly zone is likely to be motivated by their own regional interests rather than a genuine concern for the well-being of Libya’s people.

However, at this crucial time, debates about a no-fly zone should not replace conversations about solidarity. The struggle of the Libyan people for freedom deserves the strongest support. The imperative for solidarity with the Libyan rebels is being lost in anti-imperialist polemics, some of which has casually dismissed those Libyans who call for a no-fly zone as naïve or, even worse, as imperial stooges. This is disrespectful to the many Libyans who have paid a heavy price for challenging Gaddafi’s regime on the streets. A more sensible antiimperialist position would focus less on what a no-fly zone means for western powers and more on listening to Libyan voices on the ground and finding ways to meaningfully support their struggle.

The authors were in eastern Libya when the rebels declared that the area had been liberated. Anjali Kamat (akam47@yahoo.com) reports for the US-based news channel Democracy Now!. Ahmad Shokr (shokr.ahmad@gmail.com) is a doctoral candidate in the History and Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies Departments at New York University and an editor at the independent Egyptian online daily Al-Masry Al-Youm (http://www.almasryalyoum.com/en).