Ian Pannell reports: We came into the city last night and since first light, we have been hearing the amplification of artillery bombardment.

There have been gunfights in a number of areas and helicopters flying overhead.

We are hearing that there is a government offensive targeting Salah el-Din, which has been one of the most restive neighbourhoods – perhaps the key district – and which has been in the hands of the opposition Free Syrian Army for a number of days now.

We had heard that government troops were massing outside the city, though on this occasion we believe they are coming from an area they control inside Aleppo.

The rebels are saying that they have destroyed a number of tanks. Though this cannot be verified, there is evidence that they have been able to do that – they have rocket-propelled grenades and know how to use them to target these vehicles.

But the truth is they are outgunned and outmanned.

A regular trickle of trucks and cars packed with civilians has been leaving from Salah el-Din and other areas.

They have a few belongings, but not much. They don’t appear to have had much time to pack before heading out into the countryside, and safety.

It is almost impossible for us to get into some areas – one has to conclude that it would be equally difficult for residents to get out and some undoubtedly must be trapped.

The atmosphere has changed since we were here three days ago. It is eerily quiet, there are very few residents around and the mood amongst the rebels is very tense.

The commander of one of the largest brigades operating in Aleppo was even deliberating pulling his men out because he was not getting enough ammunition.

He was urged by his men not to leave – they are still here, they have been fighting this morning and wounded fighters have been brought back to the area for treatment in a makeshift clinic.

The rebels may insist in interviews that they will prevail, but the mood on the ground is different.

It is very hard not to conclude that the firepower they face is so overwhelming and Aleppo so important for President Assad’s government that resisting will be incredibly difficult, if not impossible. [Continue reading…]

Monthly Archives: July 2012

Video: The Crisis of Civilization

Rediscovering LSD

Tim Doody writes: At 9:30 in the morning, an architect and three senior scientists—two from Stanford, the other from Hewlett-Packard—donned eyeshades and earphones, sank into comfy couches, and waited for their government-approved dose of LSD to kick in. From across the suite and with no small amount of anticipation, Dr. James Fadiman spun the knobs of an impeccable sound system and unleashed Beethoven’s “Symphony No. 6 in F Major, Op. 68.” Then he stood by, ready to ease any concerns or discomfort.

For this particular experiment, the couched volunteers had each brought along three highly technical problems from their respective fields that they’d been unable to solve for at least several months. In approximately two hours, when the LSD became fully active, they were going to remove the eyeshades and earphones, and attempt to find some solutions. Fadiman and his team would monitor their efforts, insights, and output to determine if a relatively low dose of acid—100 micrograms to be exact—enhanced their creativity.

It was the summer of ’66. And the morning was beginning like many others at the International Foundation for Advanced Study, an inconspicuously named, privately funded facility dedicated to psychedelic drug research, which was located, even less conspicuously, on the second floor of a shopping plaza in Menlo Park, Calif. However, this particular morning wasn’t going to go like so many others had during the preceding five years, when researchers at IFAS (pronounced “if-as”) had legally dispensed LSD. Though Fadiman can’t recall the exact date, this was the day, for him at least, that the music died. Or, perhaps more accurately for all parties involved in his creativity study, it was the day before.

At approximately 10 a.m., a courier delivered an express letter to the receptionist, who in turn quickly relayed it to Fadiman and the other researchers. They were to stop administering LSD, by order of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Effective immediately. Dozens of other private and university-affiliated institutions had received similar letters that day.

That research centers once were permitted to explore the further frontiers of consciousness seems surprising to those of us who came of age when a strongly enforced psychedelic prohibition was the norm. They seem not unlike the last generation of children’s playgrounds, mostly eradicated during the ’90s, that were higher and riskier than today’s soft-plastic labyrinths. (Interestingly, a growing number of child psychologists now defend these playgrounds, saying they provided kids with both thrills and profound life lessons that simply can’t be had close to the ground.)

When the FDA’s edict arrived, Fadiman was 27 years old, IFAS’s youngest researcher. He’d been a true believer in the gospel of psychedelics since 1961, when his old Harvard professor Richard Alpert (now Ram Dass) dosed him with psilocybin, the magic in the mushroom, at a Paris café. That day, his narrow, self-absorbed thinking had fallen away like old skin. People would live more harmoniously, he’d thought, if they could access this cosmic consciousness. Then and there he’d decided his calling would be to provide such access to others. He migrated to California (naturally) and teamed up with psychiatrists and seekers to explore how and if psychedelics in general—and LSD in particular—could safely augment psychotherapy, addiction treatment, creative endeavors, and spiritual growth. At Stanford University, he investigated this subject at length through a dissertation—which, of course, the government ban had just dead-ended.

Couldn’t they comprehend what was at stake? Fadiman was devastated and more than a little indignant. However, even if he’d wanted to resist the FDA’s moratorium on ideological grounds, practical matters made compliance impossible: Four people who’d never been on acid before were about to peak.

“I think we opened this tomorrow,” he said to his colleagues.

And so one orchestra after the next wove increasingly visual melodies around the men on the couch. Then shortly before noon, as arranged, they emerged from their cocoons and got to work.

* * *

Over the course of the preceding year, IFAS researchers had dosed a total of 22 other men for the creativity study, including a theoretical mathematician, an electronics engineer, a furniture designer, and a commercial artist. By including only those whose jobs involved the hard sciences (the lack of a single female participant says much about mid-century career options for women), they sought to examine the effects of LSD on both visionary and analytical thinking. Such a group offered an additional bonus: Anything they produced during the study would be subsequently scrutinized by departmental chairs, zoning boards, review panels, corporate clients, and the like, thus providing a real-world, unbiased yardstick for their results.

In surveys administered shortly after their LSD-enhanced creativity sessions, the study volunteers, some of the best and brightest in their fields, sounded like tripped-out neopagans at a backwoods gathering. Their minds, they said, had blossomed and contracted with the universe. They’d beheld irregular but clean geometrical patterns glistening into infinity, felt a rightness before solutions manifested, and even shapeshifted into relevant formulas, concepts, and raw materials.

But here’s the clincher. After their 5HT2A neural receptors simmered down, they remained firm: LSD absolutely had helped them solve their complex, seemingly intractable problems. And the establishment agreed. The 26 men unleashed a slew of widely embraced innovations shortly after their LSD experiences, including a mathematical theorem for NOR gate circuits, a conceptual model of a photon, a linear electron accelerator beam-steering device, a new design for the vibratory microtome, a technical improvement of the magnetic tape recorder, blueprints for a private residency and an arts-and-crafts shopping plaza, and a space probe experiment designed to measure solar properties. Fadiman and his colleagues published these jaw-dropping results and closed shop. [Continue reading…]

Music: Robert Wyatt — ‘Sea Song’

Robert Wyatt and Annie Whitehead perform the “Sea Song” from the Wyatt’s album “Rock Bottom.”

The Palestinian dilemma over Syria

Sharif Nashashibi writes: Palestinian leaders, organisations and officials were generally silent at the start of Syria’s revolution, mainly out of concern for the fate of the half million Palestinian refugees in the country.

However, that has now changed, and not in President Bashar al-Assad’s favour. Attacks on Palestinian camps by Syrian forces loyal to him – most recently last week against the Yarmouk camp – have resulted in killings, injuries, and the displacement of thousands. This has angered Palestinian refugees, many of whom are now openly supporting the revolution, as well as taking in Syrian refugees.

This is particularly damaging for the Assad regime because it has long regarded itself as a guardian of the Palestinian cause.

In an obvious reference to Palestinians, Jihad Makdissi, the Syrian foreign ministry spokesman, wrote on Facebook that “guests” in Syria “have to respect the rules of hospitality” or “depart to the oases of democracy in Arab countries”. He later removed his comments following an outcry.

The regime’s supporters often cite the fact that Palestinian refugees in Syria are treated far better than in other Arab countries. What they overlook, though, is that the law enshrining the rights of these refugees was enacted well before the Ba’ath party took power.

While several Palestinian leaders have now broken their silence about Syria, attitudes vary. Yasser Abed Rabbo, the PLO’s secretary-general, described an attack by Assad’s forces on a Palestinian camp in Latakia as “a crime against humanity.” On the other hand, Nour Abdulhadi, the PLO’s director in Syria for political affairs, later said Palestinian refugees “will remain as supporters of the Syrian government” – a claim seemingly out of step with the facts.

One major blow to Assad has been Hamas’s stance. Not only did it refuse a request to hold pro-regime rallies in refugee camps in Syria, but it also allowed residents of Gaza to stage protests against him.

Its senior leaders left Damascus earlier this year, with political leader Khaled Meshaal – who reportedly twice turned down requests to meet Assad – now living in Qatar.

Several statements from Hamas’s top echelons have unequivocally supported Syria’s revolution. In the Washington Post, Karin Brulliard described this as a stark break between the former allies – one which, according to Fares Akram in the New York Times, strips the regime “of what little credibility it may have retained with the Arab street.”

“The policy shift [of Hamas] deprives Assad of one of his few remaining Sunni Muslim supporters in the Arab world and deepens his international isolation,” a Reuters report noted.

Hamas is the only member of the “axis of resistance” (grouping the Palestinian movement, Hezbollah, and the Iranian and Syrian regimes) to denounce Assad’s crackdown. Although Hamas’s decision is in line with polls indicating that Palestinians support the Arab spring, it has come at a significant price. A subsequent drop in Iranian aid to Hamas – which has been a lifeline for the movement in recent years – has yet to be filled by other sources. [Continue reading…]

Secret Turkish nerve center leads aid to Syria rebels

Reuters reports: Turkey has set up a secret base with allies Saudi Arabia and Qatar to direct vital military and communications aid to Syria’s rebels from a city near the border, Gulf sources have told Reuters.

News of the clandestine Middle East-run “nerve centre” working to topple Syrian President Bashar al-Assad underlines the extent to which Western powers – who played a key role in unseating Muammar Gaddafi in Libya – have avoided military involvement so far in Syria.

“It’s the Turks who are militarily controlling it. Turkey is the main co-ordinator/facilitator. Think of a triangle, with Turkey at the top and Saudi Arabia and Qatar at the bottom,” said a Doha-based source.

“The Americans are very hands-off on this. U.S. intel(ligence) are working through middlemen. Middlemen are controlling access to weapons and routes.”

The centre in Adana, a city in southern Turkey about 100 km (60 miles) from the Syrian border, was set up after Saudi Deputy Foreign Minister Prince Abdulaziz bin Abdullah al-Saud visited Turkey and requested it, a source in the Gulf said. The Turks liked the idea of having the base in Adana so that they could supervise its operations, he added.

A Saudi foreign ministry official was not immediately available to comment on the operation.

Adana is home to Incirlik, a large Turkish/U.S. air force base which Washington has used in the past for reconnaissance and military logistics operations. It was not clear from the sources whether the anti-Syrian “nerve centre” was located inside Incirlik base or in the city of Adana.

Qatar, the tiny gas-rich Gulf state which played a leading part in supplying weapons to Libyan rebels, has a key role in directing operations at the Adana base, the sources said. Qatari military intelligence and state security officials are involved.

“Three governments are supplying weapons: Turkey, Qatar and Saudi Arabia,” said a Doha-based source.

Ankara has officially denied supplying weapons.

“All weaponry is Russian. The obvious reason is that these guys (the Syrian rebels) are trained to use Russian weapons, also because the Americans don’t want their hands on it. All weapons are from the black market. The other way they get weapons is to steal them from the Syrian army. They raid weapons stores.”

The source added: “The Turks have been desperate to improve their weak surveillance, and have been begging Washington for drones and surveillance.” The pleas appear to have failed. “So they have hired some private guys come do the job.”

President Barack Obama has so far preferred to use diplomatic means to try to oust Assad, although Secretary of State Hillary Clinton signaled this week that Washington plans to step up help to the rebels.

Reuters has established that Obama’s aides have drafted a resolution which would authorize greater covert assistance to the rebels but still stop short of arming them.

The White House’s wariness is shared by other Western powers. It reflects concerns about what might follow Assad in Syria and about the substantial presence of anti-Western Islamists and jihadi fighters among the rebels. [Continue reading…]

Turkey urges steps as shelling of Aleppo continues

Reuters reports: President Bashar al-Assad’s artillery continued to pound rebel-held areas in and around Aleppo in preparation for an onslaught on Syria’s biggest city, while neigbouring Turkey called for international steps to deal with the military build-up.

Opposition sources said the shelling was an attempt to drive fighters inside Aleppo from their strongholds and to stop their comrades outside the city from resupplying them.

“They are shelling at random to instil a state of terror,” said Anwar Abu Ahed, a rebel commander outside the city.

The battle for Aleppo, a major power centre that is home to 2.5 million people, is being seen as a potential turning point in the 16-month uprising against Assad that could give one side an edge in a conflict where both the rebels and the government have struggled to gain the upper hand.

Turkish Prime Minister Recep Erdogan said late on Friday that international institutions needed to work together to address the military assault on Aleppo and Assad’s threat to use chemical weapons against external threats.

“There is a build-up in Aleppo, and the recent statements with respect to the use of weapons of mass destruction are actions that we cannot remain an observer or spectator to,” he said at a joint news conference in London with British Prime Minister David Cameron.

“Steps need to be taken jointly within the United Nations Security Council, the Organisation of Islamic Countries, the Arab League, and we must work together to try to overcome the situation,” he said.

Cameron said Britain and Turkey were concerned that Assad’s government was about to carry out some “some truly appalling acts around and in the city of Aleppo”.

Turkey, a former ally of Assad and now one of his fiercest critics, cheered on the rebels in Aleppo.

“In Aleppo itself the regime is preparing for an attack with its tanks and helicopters … My hope is that they’ll get the necessary answer from the real sons of Syria,” Erdogan said earlier in remarks broadcast on Turkish TV channels.

Millions of Americans now fall within government’s digital dragnet

Ars Technica reports: Will government surveillance finally become a political issue for middle-class Americans?

Until recently, average Americans could convince themselves they were safe from government snooping. Yes, the government engaged in warrantless wiretaps, but those were directed at terrorists. Yes, movies and TV shows featured impressive technology, with someone’s location highlighted in real time on a computer screen, but such capabilities were used only to track drug dealers and kidnappers.

Figures released earlier this month should dispel that complacency. It’s now clear that government surveillance is so widespread that the chances of the average, innocent person being swept up in an electronic dragnet are much higher than previously appreciated. The revelation should lead to long overdue legal reforms.

The new figures, resulting from a Congressional inquiry, indicate that cell phone companies responded last year to at least 1.3 million government requests for customer data — ranging from subscriber identifying information to call detail records (who is calling whom), geolocation tracking, text messages, and full-blown wiretaps.

Almost certainly, the 1.3 million figure understates the scope of government surveillance. One carrier provided no data. And the inquiry only concerned cell phone companies. Not included were ISPs and e-mail service providers such as Google, which we know have also seen a growing tide of government requests for user data. The data released this month was also limited to law enforcement investigations—it does not encompass the government demands made in the name of national security, which are probably as numerous, if not more. And what was counted as a single request could have covered multiple customers. For example, an increasingly favorite technique of government agents is to request information identifying all persons whose cell phones were near a particular cell tower during a specific time period — this sweeps in data on hundreds of people, most or all of them entirely innocent.

How did we get to a point where communications service providers are processing millions of government demands for customer data every year? The answer is two-fold. The digital technologies we all rely on generate and store huge amounts of data about our communications, our whereabouts and our relationships. And since it’s digital, that information is easier than ever to copy, disclose, and analyze. Meanwhile, the privacy laws that are supposed to prevent government overreach have failed to keep pace. The combination of powerful technology and weak standards has produced a perfect storm of privacy erosion. [Continue reading…]

Don’t believe the Skype: it may not be as private as you might think

Dan Gillmor writes: When Skype became popular just under a decade ago, I repeatedly asked the company a question that I considered crucial. The online calling and messaging service encrypted users’ communications, and it was based outside the United States. But the encryption methods were kept secret, so outside researchers couldn’t verify their quality – a technique that experts in the field sometimes deride as “security through obscurity” – and I wanted to know whether Skype had a software backdoor that it or anyone else could use to listen into users’ calls. I was repeatedly given a non-denial denial – that is, an assurance that the information was being encrypted but no guarantee beyond that. So I assumed that Skype shouldn’t be considered a foolproof way to have an absolutely private conversation.

That assumption grew firmer when eBay bought Skype in 2005, putting Skype under American legal jurisdiction at a time when the Bush administration was routinely and illegally spying on citizens’ communications and Congress was a partner in destroying civil liberties. Moreover, eBay had a reputation for giving law enforcement just about anything it requested under just about any pretext.

Washington’s attitudes are, if anything, more police-statish than before. The Republicans don’t believe in any restraints on police, while Democrats who hated the Bush policies are supine now that the Obama administration has, if anything, expanded on the worst of the prior administration’s practices. And Skype now is part of Microsoft. So I am yawning at a spate of reports, most recently in the Washington Post, that Microsoft is giving law enforcement what torture fans might call “enhanced access” to Skype users’ conversations. The company’s statement on the matter says no recent changes have been made; but Skype also says this: “Skype takes appropriate organisational and technical measures to protect your information within our control with due observance of the applicable obligations and exceptions under the relevant law.”

To be clear, I don’t know one way or the other whether Skype has been secretly helping police and security officials listen in on conversations. I do know that the company, as in its statement above, persists in giving non-answers to the question. [Continue reading…]

Video: Robin Hood tax to the rescue?

As Aleppo braces for a bloodbath, Syria’s regime is far from beaten

Tony Karon writes: The ancient and storied city of Aleppo is shaping up to be the next great bloodbath of Syria’s 18-month rebellion. The regime is concentrating its elite forces, and their armor, artillery and air support, for an all-out assault to recapture those parts of the city seized by insurgents. The outcome will likely mirror last week’s battle in Damascus, where President Bashar al-Assad’s forces eventually forced the rebels to retreat. Not even the rebels are expecting to be able to hold the city against the regime’s overwhelming firepower, and its determination to stop Syria’s largest and most prosperous city falling to the rebellion. But Aleppo will not be the final or decisive battle of the war. Instead, it will more likely confirm a strategic stalemate, in which the regime is unable to destroy the rebellion, but the rebellion lacks the military power to destroy the regime. There may yet be many weeks and months of carnage ahead.

Having watched Assad bludgeon his rebellious citizenry for the past 18 months, the international media is understandably impatient to see the bloodletting brought to an end with the regime’s collapse. Perhaps it was that impatience — or the audacity of a rebel offensive in the capital, that included a devastating strike on the regime’s key command center that killed four of Assad’s top security aides, followed by the opening of a second front in Aleppo — that shifted the tone of coverage to one anticipating the regime’s rapid demise. But after the initial shock of last week’s events in Damascus, the regime regained its footing and systematically, and brutally, drove the rebels out of most of the neighborhoods they had seized in the capital. The outcome in Aleppo may be similar.

“Aleppo is a complex city,” a local rebel supporter identified only as Amir told the Guardian. “You can see people support the regime, those who are fearful and those who are pro-revolution. The middle and upper classes don’t want the rebels to come in. They want everything to be business as usual. No one can can predict what will happen but there is unhappiness that the rebels have brought all this firepower down on Aleppo.” By that description the rebels may have neither the firepower, nor the consensus within the city, necessary to hold it in the face of the counter-attack expected Friday or Saturday. Despite the many setbacks it has suffered and the clear sense that it is beyond Assad’s power to restore the status quo ante, his regime is far from beaten. Nor were the rebels necessarily expecting that their assaults on Damascus and Aleppo marked the final offensive.

The 1968 Tet Offensive, staged by the Vietcong revolutionaries against the U.S. and the local allies it was propping up in Vietnam, bears consideration here. As the lunar New Year dawned on January 30, 1968, tens of thousands Vietcong insurgents mounted simultaneous surprise attacks on command and control centers in more than 100 villages, towns and cities, including dramatic attacks on six key command centers (including the US Embassy) in South Vietnam’s capital, Saigon. They took control of the old imperial capital of Hue for close to a month, as well as besieging the U.S. base at Khe Sanh for three months. Although the Vietcong suffered massive casualties and were forced to yield those gains, the operation negated Washington’s triumphalism and convinced Americans that the Vietnam war was unwinnable. The offensive was in no sense a final assault on the bastions of U.S. power and the allies it propped up in South Vietnam. Their purpose, instead, was to send a political message: the U.S. and its allies would never eliminate the Vietcong.

There are, of course, countless differences between the situation in Syria today and what transpired in Vietnam 44 years ago, but the Tet analogy may still hold: Syria’s rebels have proved in recent weeks that the regime will not be able to restore its grip over all of the country, or to crush the rebellion by force. For many Syrians, that signals the inevitability of a change of regime — a realization that will convince many of Assad’s less committed allies to switch sides or seek alternatives. So, even if they haven’t brought the regime to the brink of collapse, the rebel offensives in Damascus and Aleppo have dramatically weakened the regime, forcing its Syria and foreign allies to begin reassessing their options. [Continue reading…]

Russia’s fear of radical Islam drives its support for Assad

Amal Mudallali writes: It was no coincidence that Russia vetoed a Security Council resolution on Syria just hours after twin attacks killed a moderate Muslim official and injured the Mufti in the central Russian republic, Tartarstan, last week. Russia sees the assassination as a direct attack on moderate Islam by Islamic radicals. And the veto, Russia’s third since the Syrian crisis began, is grounded in a deep-rooted policy of war against one enemy: Islamic radicals.

Russia supports Syrian President Bashar al-Assad because of a strategic relationship and what it views as the same fight in Syria and Russia against the Salafi and extremist Islamic threat.

Since the beginning of the Syrian revolution, Russia has accepted the official government line and branded the opposition as terrorists, Islamic radicals or Salafists. A wide array of explanations have been given by Russia, as well as the West, for its support of Assad, some of which are to the detriment of Russian interests in the Arab world. They cited strategic assets that the Russian Navy has in a Mediterranean seaport, arms sales to the Syrian military, a general East–West rivalry, and even Russian President Vladimir Putin’s refusal, “on principle,” of the removal of national leaders by outside intervention. But the Russian position is actually rooted in a deep-seated fear, and sometimes paranoia, of the spread of Islamic radicalism.

This factor in defining Russian policy has received scant attention. Russia does not see itself as an ally of Assad, but as a target, like him, of a Salafi-terrorist plot to destabilize Russia — just as they are doing in Syria, with help from the West. Even when regime forces massacred over 100 women and children in Houla, the Russians blamed the Wahabis, the Saudi form of Islam. After 18 months of bloodshed and over 15,000 dead, it becomes increasingly difficult to reconcile Russia’s reading of the situation in Syria with Assad’s brutal one.

Putin’s government sees the Islamic threat as one of the most important challenges to the Russian state and its neighboring countries. Most of these states have restless, largely Muslim, populations and one form or another of dictatorship. So the Russians are fearful that change in these countries might bring Islamic radicals to power and Russia will be encircled by extreme Muslim regimes. [Continue reading…]

Video: Your irrational brain

In shift by Egypt, president meets Hamas leader

Reuters reports: Gaza Islamist leader Ismail Haniyeh met Egyptian President Mohamed Mursi on Thursday in an official visit that signaled a big shift in Cairo’s stance toward the Hamas movement after the election of a Muslim Brotherhood head of state in Egypt.

A Palestinian official said the head of Egyptian intelligence had promised measures to increase the flow of fuel supplied by Qatar to Gaza via Egypt and needed to ease the small Palestinian territory’s power shortages. The sides had also discussed increasing the flow of Palestinians across the border.

But there was no immediate sign that Cairo was ready to open up its border with Gaza to the extent sought by Hamas, something analysts partly attributed to the influence still wielded by the Hosni Mubarak-era security establishment.

“Mursi’s heart is with Hamas but his mind is elsewhere,” said Hany al-Masri, a Palestinian political commentator. “He will give them as much as he can but he won’t be able to give them much because his powers are restricted,” he said.

Mursi’s victory was celebrated in Gaza as a turning point for a territory whose economy has been choked by a blockade imposed by Israel and in which Egypt took part by stopping everything but a trickle of people from crossing the border.

But as head of state, Mursi must balance support for Gaza with the need to respect international commitments, including Egypt’s peace treaty with Israel. “He will be very cautious,” said Mustapha Kamel Al-Sayyid, an Egyptian analyst. “The intelligence and the military will have their say on this.”

Video: Palestinian going for gold at Olympics

My 50 minutes with Manaf Tlass

While Western powers and their Arab allies weigh up Brig. Gen. Manaf Tlass and his potential as Assad-replacement material, one observer provides a much more telling view of a man who appears to embody continuity much more than change.

Bassam Haddad writes: Tala was a friend of a friend. I met her in the early 2000s. Shortly afterward, she disappeared from the office. It turns out she got married.

Some years later, during one of my regular visits to Syria, I was with a group of friends at one of the bustling new restaurant-bars that dotted Damascus’ old city, around Bab Touma. Some places were more popular than others, frequented by internationals and a particular stratum of Damascene society that included some people who were pro-regime and others who were opposed. By the mid-2000s, one’s opinion of the regime did not matter much, in and of itself. What brought these Damascenes together was their common benefit from President Bashar al-Asad’s “economic reform” policies and the social stratification they had produced. In these circles, criticism of the regime was no longer taboo — so long as it was presented in a pleasant and “reasonable” manner. No names, no mention of sect, nothing “subversive.” Anyway, why would these people want to subvert the status quo?

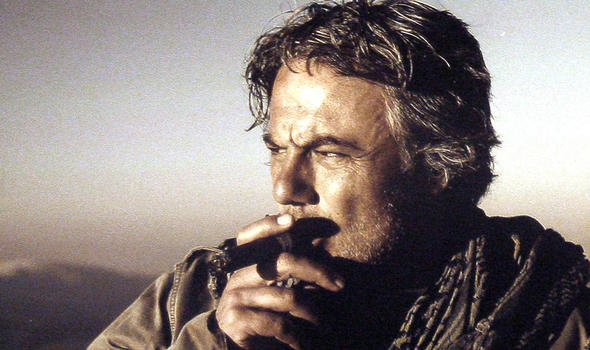

That night, I was introduced to Tala’s husband, Manaf Tlass, as a “Syria researcher” working on the “Syrian economy.” At the time, Manaf was one of the regime’s top strongmen, working side by side with Mahir al-Asad (the president’s younger brother) as a commander of elite units in the Republican Guard. It was too dark to make out his features. Most of what I saw was the big round flame at the tip of the cigar that seemed surgically attached to his fingers, if not his lips. He asked a few questions. I answered politely. I knew who he was, and thought it was odd that he mingled so freely.

That was it.

On a subsequent trip, at a birthday party in another of those restaurants, I met Manaf again. This time, he asked someone to ask me to come to his table. Usually, that is not a good thing. I obliged, and he took me aside, asking more questions about regional politics and, then, Syria. I found myself discussing post-colonial development with Manaf and his cigar as Stardust’s remix of “Music Sounds Better with You” played in the background. We talked for a few minutes before I excused myself. Later, as he said his goodbyes to his fellow diners, Manaf approached me and asked me to come to his home office in Mazzeh. I was not asked for my cell phone number but was given an office number to confirm the visit.

I was in a tricky position. My research on Syrian political economy examined state-business networks and traced the deepening relationships between state officials and businessmen.

Manaf Tlass was no businessman, having gone the route of his father, Mustafa, the former defense minister who was a close confidante of Hafiz al-Asad for decades. But his brother, Firas, was. Many offspring of the Syrian leadership had gone the entrepreneurial route, and by the late 1980s they had become big businessmen, often with the aid of connections to consummate insiders like Manaf. Firas Tlass is said not to have exploited his connections as much as others, but the fact is that policymakers and policy takers in Syria were increasingly bound together. And there was another model that proved even more efficient at generating profits: The state official himself was a businessman in his capacity as a private citizen, creating what I called “fusion” between the public and private sectors.

For about ten years, I had been trying to study the development of capitalism in Syria, how it sustained authoritarianism and the attendant social machinations. I was not interested in exposing this or that character, as the “fusion” formula is not unique to Syria, and the Syrian regime was in no need of further unmasking. I purposely avoided talking to government and regime figures because the returns from such interviews are usually meager, and there is always the risk of raising suspicions about one’s research. The last systematic fieldwork by a Western scholar on Syria’s political economy had been carried out by Volker Perthes a decade earlier, producing the staple book The Political Economy of Syria Under Asad (1995). It was not a walk in the park for Volker, and nor was it for me. Though Firas Tlass, the fast-growing tycoon, was quite accessible, I elected not to speak with him, relying instead on an interview Joseph Samaha, one of the best journalists of our time, had conducted for al-Hayat in 1999. But now Firas’ brother, on the other side of the state-business equation, wanted to speak with me. It was not easy to say yes or no.

Manaf was quite candid and seemed more interested in conversation than surveillance. Still, I hesitated for some time before friends advised me not to skip out on the meeting.

At the time, Manaf was a rising star, quite close to the Asad family. Regime strongmen had regained their swagger after several years of “consolidation” that took place after the succession of Bashar to the presidency. It was a day to begin making Syria anew, with a younger and more contemplative, though less seasoned, leadership. The theme was less “reform” than “modernization,” less “change” than “continuity.” There was an atmosphere of cautious openness.

I walked into Manaf’s office and was politely asked to sit. I politely turned down the offer of a cigar. After some back-and-forth about my heritage (my mother is Syrian), Manaf asked me to share with him my frank thoughts about the Syrian regime, without stammering or self-censorship. It was surreal.

I was not unafraid. But I spoke forthrightly because it was the only thing I could do, and, honestly, because Manaf’s bearing was anything but intimidating or reminiscent of the stereotypical interrogator.

Taking care to be respectful, I shared my views on the limits of authoritarianism in time and space, and the limits of Syria’s regional role in the absence of more inclusive power-sharing formulas inside the country. When Manaf asked about corruption, I made sure to repeat, almost verbatim, the words of ‘Arif Dalila, an independent Marxist economics professor at the University of Damascus who was incarcerated in 2001 for his anti-regime views, during the post-“Damascus spring” round of arrests. ‘Arif was one of the most courageous people around — a mentor and, later, a friend. In 1998-1999, under Asad senior, mind you, when mosquitoes shuddered at the thought of landing on a regime member’s nose, he would walk down the aisle of the packed auditorium at the Tuesday Economic Forum. He would take the stage and dismantle the state’s rhetoric regarding the causes of Syria’s economic decline after the mid-1990s. He would say to rooms crawling with informants (and worse), and I quote from my notes:

Corruption is not a moral or ethical problem at heart, and it does not start at the moment when a policeman or border officer asks for a bribe. It is a systemic practice with a social, economic and political material base intended to sustain the entire political formula in this country…. We should not blame the poor officer who cannot make ends meet on his salary, but instead we should demand accountability at the highest level possible in this regime.

Talk about goose bumps. It was scary just to witness those words uttered. The room would fall silent, as though everyone had literally died, but everyone was actually feeling hyper-alive as ‘Arif would yifish al-ghill (redeem) the listeners in the most visceral way. Almost immediately after he spoke, over half of the audience would leave. It was one of the reasons why the Forum’s general secretary, Farouq al-Tammam, would beg ‘Arif to postpone his intervention until the end, knowing that everyone would stay to hear him. ‘Arif was not just a political economist or regime critic. He was a visionary, versed in the intricacies of global politics, and someone who would tear up when discussing the loss of Palestine by Arab regimes, including Syria’s.

Manaf listened without interrupting, and without letting go of his cigar. He then responded for 20 minutes, challenging me mildly on the feasibility of genuine reform in Syria and giving his views on democracy, the United States and regional politics. He was also forthright. His ideas, however, were underdeveloped or, more precisely, developed in a mind accustomed to wielding excessive power. [Continue reading…]

In Syria, ‘Jihad is not al Qaeda’

Media references to jihadists in Syria typically portray them as a predominantly foreign, necessarily extremist, and largely opportunistic element in the uprising. Their intent, we are so often told, is to hijack the revolution. A report for Time magazine by Rania Abouzeid presents a much more nuanced picture.

In late January, the jihadist group Jabhat al-Nusra li Ahl Ash-Sham, or the Support Front for the People of Syria, announced its formation and its goal to bring down the regime of President Bashar Assad. In the months since, it has claimed responsibility for many of the larger, more spectacular bombing attacks on Syrian state security sites, including a double suicide car bombing in February targeting a security branch in Aleppo that left some 28 dead.

Little is known about the shadowy group, beyond that it is headed by someone using the nom de guerre Abu Mohammad al-Golani (Golani is a reference to Syria’s Golan Heights, occupied by Israel.) Some say the group is a regime creation, to prove Assad’s assertion that he is fighting terrorists, while others say it is an offshoot of the al-Qaeda group the Islamic State of Iraq.

A foot soldier in the movement told TIME that it is neither. “We are just people who follow and obey our religion,” the young man, Ibrahim said. “I am a mujahid, but not al-Qaeda. Jihad is not al-Qaeda.”

It took weeks of negotiations to secure an interview with a member of the movement, the first time anyone from the group has talked to the media. Higher-ups in the Jabhat declined to be interviewed but agreed to let Ibrahim, a 21-year-old Syrian, be interviewed.

The Jabhat has a presence in at least half a dozen towns in Idlib province, as well as elsewhere across the country, including strong showings in the capital Damascus and in Hama, according to the Jabhat member and other Islamists who are in contact with senior members of the group.

Bespectacled, with a wispy beard and thin mustache, Ibrahim said he joined the group eight months ago. He was recruited by his cousin Ammar, the military operations commander for their unit and a Syrian veteran of the Iraq war who fought alongside his Sunni co-religionists against the American invaders. (Ammar declined to be interviewed.)

Dressed in a deep aqua blue zippered track top and black track pants that were rolled up above his ankles, the young man did not look as menacing as some of his colleagues, with their short pants and above-the-ankle-galabiyas and long beards. In addition to his self-identification as a member of the Jabhat, several Free Syrian Army rebels who know him — as well as townsfolk who know his conservative Sunni family — confirmed that Ibrahim is part of the extremist group.

“Our specialty is explosives, (improvised explosives) devices. Most of our operations are explosions using (IEDs), placing them on roads, blowing up cars by remote detonation,” Ibrahim said. On the night TIME spoke to him, several members of the Jabhat were in a remote field, in the final stages of testing a homemade rocket devised with the help of Syrian veterans of the Iraq war.

The device was a copper-lined shaped charge that could penetrate armor. When the device ignited, the copper element superheated enough to pierce a tank. “It’s a very simple idea, but it works,” Ibrahim said, adding that the device was the work of the Jabhat’s engineering branch. “There’s a killing branch, I’m in the killing and chemical branch,” he said, explaining the chemical branch was responsible for obtaining the fertilizers and other components of the IEDS.

There were 60 men in Ibrahim’s unit, he said, headquartered in a nondescript building that flew two white flags bearing a stylized Muslim Shahada — ‘There is no God but God and Mohammad is the messenger of God.” (…[I]t’s more common to see the Shahada printed in white on a black background. The local printer, a sympathizer, said he reversed the colors “so that people don’t think we have al-Qaeda here.”)

The Jabhat members maintain a low profile, and keep to themselves, townsfolk said, adding that they rarely ventured outside their outpost except to head to battle. “The shabab (young men) prefer to remain in the shadows, unseen, they won’t come forward,” Ibrahim said. Their low profile also enabled some members “not known to the security forces” to pass through checkpoints, especially in and around Damascus and the northern commercial hub of Aleppo, which is currently facing aerial bombardment from Assad’s forces as well encirclement by an approaching armored column. The secrecy extended to the group’s members. “We don’t really like to accept people we don’t know. We don’t need foreigners,” Ibrahim said, although he admitted there were some foreign jihadists in his group from Kuwait, Libya and Kazakhstan.

He was fighting because he wanted to “live in freedom.” His idea of freedom, however, was an Islamic state, free of “oppression” by members of President Assad’s privileged sect, the Alawites. “The Alawites can do what they want and we have no say, that’s why we are fighting, because we are oppressed by them,” he said. “We are nothing to them. They are the head, and we are nothing.”

In another town in northern Idlib, another jihadist — belonging to a different group — also shared Ibrahim’s goal of an Islamic state. “Abu Zayd,” is a 25-year-old Sharia graduate who heads one of the founding brigades of Ahrar al-Sham, a group that adheres to the conservative Salafi interpretation of Sunni Islam.

He said minorities had nothing to worry about in any future Islamic state, despite the increasingly sectarian nature of some of the violence that has convulsed Syria. “Let’s consider that Syria becomes something other than Islamic,” he said, “a civil state. What is the role of the Alawites in it? What is the position of a Christian, a Muslim in it? They are all under the law, and it will be the same in an Islamic state. We are just exchanging one law for another.”

The young Syrian, with his neatly trimmed beard, dressed in military pants and a blue t-shirt, looked more like a member of the FSA than a Salafist. His facial hair was not fashioned in the manner of some Salafists, who shave their mustaches. (Interestingly, many FSA members have taken to wearing Salafi-style beards while not adopting the ideology. “It’s just a fashion,” one person told me, by way of explanation.)

The Ahrar started working on forming brigades “after the Egyptian revolution,” Abu Zayd said, well before March 15, 2011 when the Syrian revolution kicked off with protests in the southern agricultural city of Dara’a. The group announced its presence about six months ago, he said. Abu Zayd denied the presence of foreigners even though TIME saw a man in the group’s compound who possessed strong Central Asian features. “Maybe his mother is,” Abu Zayd said unconvincingly. “We are not short of men to need foreigners.”

Regardless, foreigners are coming across into Syria. One prominent Syrian smuggler in a border town near Turkey said that he ferried 17 Tunisians across the night before. It was a marked uptick in his business. He said he hadn’t seen many foreign fighters for about a month prior to the Tunisians. “Before that, every day there were new people, from Morocco, Libya, and elsewhere,” he said. (In the course of several hours of waiting to cross back into Turkey, I saw at least a dozen Arabs who were clearly not Syrian, and identified as foreigners by the smuggler.)

It’s unclear how large the Jabhat and Ahrar are, given their shadowy nature, but it’s clear that their activities are becoming more public. Both participate in operations alongside regular FSA units, although some FSA commanders remain suspicious of them and jealous of the deep Gulf pockets funding them. “Where were the Islamists when the revolution started?” is spray-painted on the wall of one town in Idlib. The response, spray-painted beneath it, was equally curt: “In prison.” [Continue reading…]