Pankaj Mishra writes: There has rarely been a day since I first read The Need for Roots, nearly two decades ago, that I haven’t thought of Simone Weil – one of my earliest heroines along with Hannah Arendt and Rosa Luxemburg. It was the title that initially attracted me more than the contents. Having recently moved to a Himalayan village after a peripatetic life in the plains, I had begun to feel rooted for the first time, connected to a stable community which, living off the land, neither poor nor rich, and low rather than upper caste, was marked above all by dignity – remarkable in a country where villages had become synonymous with destitution. And when Weil asserted that the central event of the modern era was uprootedness – the disconnection from the past and the loss of community – she seemed to speak directly to my experience.

The range of her admirers – from TS Eliot to Albert Camus – attest to the difficulty of describing Weil. She was a bourgeois Jewish intellectual from France who, in a viciously antisemitic climate, rejected both Judaism and Zionism. A youthful Marxist who fought on the Republican side in the Spanish civil war she, after an immersion in the “icy pandemonium of industrial life”, came to believe that “it is not religion but revolution which is the opium of the people”. A devoted Hellenist, she despised the Roman empire, implicating it with an oppressive tradition of the authoritarian state in Europe that culminated in Nazi Germany.

A rare European thinker who was as curious about Hindu and Buddhist traditions as about the Cathars, Weil despised colonialism as well as nationalism. “When one takes upon oneself, as France did in 1789, the function of thinking on behalf of the world, of defining justice for the world, one may not become an owner of human flesh and blood.” She possessed an ironic view of historians – how they buttress the ideological claims of the hyper-power of the day: “If Germany, thanks to Hitler and his successors, were to enslave the European nations and destroy most of the treasures of their past, future historians would certainly pronounce that she had civilised Europe.”

Freed of the popular intellectual’s obligation to boost national or imperial egos, she could point out something that was obvious to many Asian sufferers of European colonialism: the shocking nature of Nazi racism lay, she wrote, “in the application by Germany to the European continent, and the white race, generally, of colonial methods of conquest and domination”. [Continue reading…]

Category Archives: global culture

Eric Hobsbawm: A British internationalist

Ramachandra Guha writes: In 1980, as a beginning graduate student, I was directed by my thesis supervisor to a short, pungent piece by Eric Hobsbawm that had just appeared in the journal Past and Present. This was a response to a previous essay in the same journal, by Lawrence Stone, that celebrated the “revival of narrative” in historical writing. In Stone’s view, this was a welcome departure from the arid, analytical, social-scientific and (not least) Marxian trends that had previously dominated the discipline. Hobsbawm, who died on Monday at the age of 95, saw Stone’s triumphalism as misplaced; to be sure, historians needed to write well, but they had also to analyse and synthesize, to explain events and processes in terms of what they meant to human values and institutions.

I first read Hobsbawm in 1980; I last read him in 2011, when seeking to understand an armed insurgent named Kishenji much written about in the Indian press. The man saw himself as an Indian Mao Zedong, who would one day capture state power in New Delhi; but he seemed rather to be what Hobsbawm called a “social bandit,” raiding the rich and killing policemen while being given refuge by the peasants and tribals with whom he identified. From Hobsbawm I learnt to see Kishenji as a figure of romance and daring but — despite his inflated self-image and the paranoia of the right-wing press — of no real historical or political significance.

I never met Eric Hobsbawm, yet he has kept me company throughout my working life. I suspect my experience is representative — other Indian, African and Latin American historians who never saw the man in the flesh likewise read his work very closely. And there was a great deal for us to read: some 30 books published over seven decades of a very long life and very active career. [Continue reading…]

Video: The Crisis of Civilization

Future will be shaped by the rise of the angry young man

Afshin Molavi writes: Last October, amid the din of the Arab uprisings, the euro-zone crisis, the lingering effects of the Japan earthquake, and the US gearing up for a election season, a quiet milestone was passed: the world population hit the seven billion mark.

This is, on one level, very good news. It means that advances in medicine, nutrition, and education over the past six decades have dramatically raised life expectancies, reduced infant mortality rates, and eradicated previously fatal diseases. Over the past 60 years, we have become healthier and wealthier than at any time in human history – and yet, still, we stand on a precipice.

Of those seven billion humans on our planet, nearly half are under the age of 24.

In many of the poorest and developing countries, those numbers are even more stark, with 60 to 70 per cent of the population falling into that age group, particularly in poor and developing countries unable to cope with the demands of young populations. For example, three out of four Nigerians are under 35. In Yemen, the numbers are even more stark. Three out of four are 25 or under. Across the Middle East and North Africa region, two out of three people are 29 or younger.

We are currently living amid the largest cohort of youth in human history. Young populations can be a demographic gift or a demographic bomb. A gift when governments effectively employ them, deriving sustainable productive value from their labour while the young people derive meaningful work experience, raise their incomes, marry, have children, invest, and continue the cycle of life.

The next decade, however, will likely see some demographic bombs blowing up across the world as youth bulges push against weak or underperforming economies and unemployment and underemployment plague societies from Nigeria to Pakistan, from Egypt to large parts of India and sub-Saharan Africa, and in many European countries.

While this environment will inflict damage on men and women alike, the effect on young men will prove to be more destabilising.

The world over the next decade will be defined by the Angry Young Man, born amid this historic baby boom, and now entering the netherworld between youth and adulthood, unable to find a job, angry at his government, hyper-aware of the inequalities around him, frustrated by corruption, and connected to the outside world through social networking sites and satellite television. From Avenue Habib Bourguiba in Tunis to Tahrir Square in Cairo, from Athens and Tehran to Delhi and Karachi, the angry young man, fist pumping the air, has become a feature of our world. [Continue reading…]

World lacks enough food, fuel as population soars: U.N.

Reuters reports: The world is running out of time to make sure there is enough food, water and energy to meet the needs of a rapidly growing population and to avoid sending up to 3 billion people into poverty, a U.N. report warned on Monday.

As the world’s population looks set to grow to nearly 9 billion by 2040 from 7 billion now, and the number of middle-class consumers increases by 3 billion over the next 20 years, the demand for resources will rise exponentially.

Even by 2030, the world will need at least 50 percent more food, 45 percent more energy and 30 percent more water, according to U.N. estimates, at a time when a changing environment is creating new limits to supply.

And if the world fails to tackle these problems, it risks condemning up to 3 billion people into poverty, the report said.

Efforts towards sustainable development are neither fast enough nor deep enough, as well as suffering from a lack of political will, the United Nations’ high-level panel on global sustainability said.

What happens when the economy stops growing — forever?

Revolt without revolution

Slavoj Žižek writes:

Repetition, according to Hegel, plays a crucial role in history: when something happens just once, it may be dismissed as an accident, something that might have been avoided if the situation had been handled differently; but when the same event repeats itself, it is a sign that a deeper historical process is unfolding. When Napoleon lost at Leipzig in 1813, it looked like bad luck; when he lost again at Waterloo, it was clear that his time was over. The same holds for the continuing financial crisis. In September 2008, it was presented by some as an anomaly that could be corrected through better regulations etc; now that signs of a repeated financial meltdown are gathering it is clear that we are dealing with a structural phenomenon.

We are told again and again that we are living through a debt crisis, and that we all have to share the burden and tighten our belts. All, that is, except the (very) rich. The idea of taxing them more is taboo: if we did, the argument runs, the rich would have no incentive to invest, fewer jobs would be created and we would all suffer. The only way to save ourselves from hard times is for the poor to get poorer and the rich to get richer. What should the poor do? What can they do?

Although the riots in the UK were triggered by the suspicious shooting of Mark Duggan, everyone agrees that they express a deeper unease – but of what kind? As with the car burnings in the Paris banlieues in 2005, the UK rioters had no message to deliver. (There is a clear contrast with the massive student demonstrations in November 2010, which also turned to violence. The students were making clear that they rejected the proposed reforms to higher education.) This is why it is difficult to conceive of the UK rioters in Marxist terms, as an instance of the emergence of the revolutionary subject; they fit much better the Hegelian notion of the ‘rabble’, those outside organised social space, who can express their discontent only through ‘irrational’ outbursts of destructive violence – what Hegel called ‘abstract negativity’.

There is an old story about a worker suspected of stealing: every evening, as he leaves the factory, the wheelbarrow he pushes in front of him is carefully inspected. The guards find nothing; it is always empty. Finally, the penny drops: what the worker is stealing are the wheelbarrows themselves. The guards were missing the obvious truth, just as the commentators on the riots have done. We are told that the disintegration of the Communist regimes in the early 1990s signalled the end of ideology: the time of large-scale ideological projects culminating in totalitarian catastrophe was over; we had entered a new era of rational, pragmatic politics. If the commonplace that we live in a post-ideological era is true in any sense, it can be seen in this recent outburst of violence. This was zero-degree protest, a violent action demanding nothing. In their desperate attempt to find meaning in the riots, the sociologists and editorial-writers obfuscated the enigma the riots presented.

The protesters, though underprivileged and de facto socially excluded, weren’t living on the edge of starvation. People in much worse material straits, let alone conditions of physical and ideological oppression, have been able to organise themselves into political forces with clear agendas. The fact that the rioters have no programme is therefore itself a fact to be interpreted: it tells us a great deal about our ideological-political predicament and about the kind of society we inhabit, a society which celebrates choice but in which the only available alternative to enforced democratic consensus is a blind acting out. Opposition to the system can no longer articulate itself in the form of a realistic alternative, or even as a utopian project, but can only take the shape of a meaningless outburst. What is the point of our celebrated freedom of choice when the only choice is between playing by the rules and (self-)destructive violence?

Hypocrisy is the tribute vice pays to virtue

Must-read commentary from Pankaj Mishra:

There were chuckles and sniggers in Qatar last month when Hillary Clinton, the US secretary of state, warned that a military dictatorship was imminent in Iran. Threatening America’s most intransigent adversary, Clinton seems to have been oblivious to her audience: educated Arabs in the Middle East where America’s military presence has long propped up several dictators, including such stalwart allies in rendition and torture as Hosni Mubarak.

Of course, by her own standards, Clinton was being remarkably nuanced and sober: during the presidential campaign in 2008 she promised to “obliterate” Iran. An over-eager cheerleader of the Bush administration’s serial bellicosity, Clinton exemplifies Barack Obama’s essential continuity with previous US foreign policymakers – despite the president’s many emollient words to the contrary. Clinton has also “warned” China with an officiousness redolent of the 1990s when her husband, with some encouragement from Tony Blair, tried to sort out the New World Order.

But the illusions of western power that proliferated in the 90s now lie shattered. No longer as introverted as before, China contemptuously dismissed Clinton’s warnings. The Iranians did not fail to highlight American skulduggery in their oil-rich neighbourhood. But then Clinton is not alone among Anglo-American leaders in failing to recognise how absurdly hollow their quasi-imperial rhetoric sounds in the post-9/11 political climate.

Visiting India last year David Miliband decided to hector Indian politicians on the causes of terrorism, and was roundly rebuffed. Summing up the general outrage among Indian elites, a leading English language daily editorialised that the British foreign secretary had “yet to be house-trained”. The US treasury secretary, Timothy Geithner, provoked howls of laughter in his Chinese audience when he assured them that China’s assets tied up in US dollars were safe.

As foreign secretary of a nation complicit in two recent terrorist-recruiting wars, Miliband could have been a bit more modest. Resigned to financing America’s massive deficits with Chinese-held dollars, Geithner could have been a bit less strident.

But no: old reflexes, born of the victories of 1945 and 1989, linger among Britain and America’s political elites, which seem almost incapable of shaking off habits bred of the long Anglo-American imperium – what the American diplomat and writer George Kennan in his last years denounced as an “unthought-through, vainglorious and undesirable” tendency “to see ourselves as the centre of political enlightenment and as teachers to a great part of the rest of the world”.

Read the whole article.

American power and the fall of modernity

American power and the fall of modernity — Part I

Modernity is still rooted in a framework of state religious nationalism. Yes, modernity made the state the arbiter of identity. For two centuries and more, collective belonging and meaning has been a state enterprise. In the great religious wars of the 20th century, millions willingly sacrificed themselves for the sacred vision of the nation-state.

Yet now that very vision is in deep recess or near-death, even as the regulatory structures of nation-states keep expanding. Western modernity’s claim of religious nationalism died in the killing fields of the last century — and with it the power of Western identity.

The air is coming out of modernity’s tires — first in the marginal places run by European colonialism, and then increasingly in the places where modernity began. Where it falters, other cultural forms rise to take up the slack. Thus, states are not weakening or failing because of “radical” or “illicit” threats.

In their stead — especially in the faux nation-states sloughed off by European colonialism — equally passionate local and universalistic visions have risen up. They lay their claims not in the consumer and social welfare-driven economies of the developed world, but with societies in need. They flourish where the demand for identity is greatest.

Modernity left a legacy where much of humanity is desperately in need of something new to belong to — and hold on to.

Today 60% of human society has been left behind. Scores of so-called nation-states cannot support raw human needs — or simply care not to — and billions are effectively being abandoned. [continued…]

Drug wars and faltering states: the demise of national identity — Part II

Our 40-year “War on Drugs” merely showcases how U.S. drug demand translates into a field of distortion that has cleared a swath of pure cultural destruction from Mexico to Ecuador.

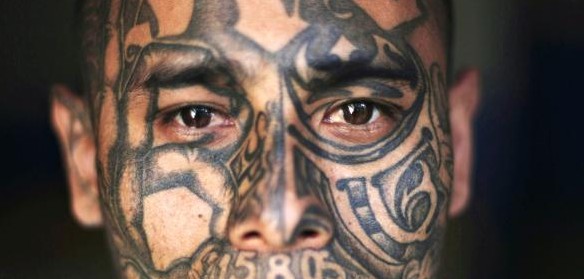

What of gangs like Mara Salvatrucha, created by the U.S. war in El Salvador in the 1980s?

Of those refugee kids who came to the United States — only to be re-exported by us back to the slums of San Salvador in the 1990s — as many as 50,000 quickly became the shock troops of a U.S.-inspired transnational gang enterprise.

What did they begin to do when they got back home? They started taking over the country. This was a fully funded American disruption. [continued…]

American power and the fall of modernity — Part III

Moving away from modernity’s religious nationalism need not necessarily presage a world of disorder.

Rather, it suggests a world where both local and universalistic identities interact equally with the remnants of the nation-state.

We see this in the world of Islam and elsewhere with the surge of Pentecostal evangelism in Africa.

The state is supplanted in much of Africa by an intricate weave of non-state actors. Many of them are intimately connected to non-state actors in the developed world — such as missionary groups tied to the Arab region, Iran and Texas — and to Western NGOs for assistance in aid and administration.

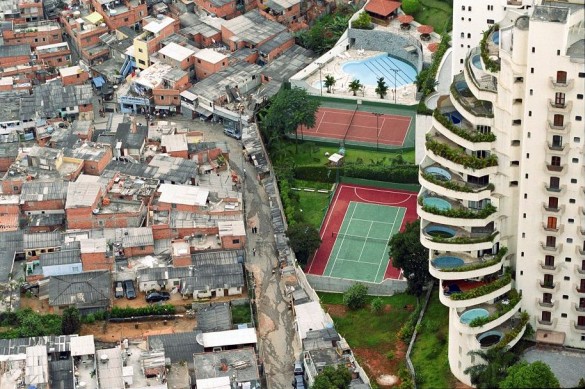

But even in societies with working state administrations, the non-state continues to flourish. Look at Brazil and Mexico. While the state remains effective, its base is shrinking to those more elite constituencies for whom it provides real security and services.

But even in societies with working state administrations, the non-state continues to flourish. Look at Brazil and Mexico. While the state remains effective, its base is shrinking to those more elite constituencies for whom it provides real security and services.

Meanwhile in the developed world, modernity’s first nation-states have neither the money nor the commitment to reclaim their lost stature and authority in the human ecology of today’s non-state.

Many, like the EU and Russia, feel their own national identities besieged. They fear being overwhelmed by the “other” in their own countries. Their national energies are increasingly tasked to immigration management and strategies of minority assimilation — or maybe just mitigation.

This is not a world of tariff-based deglobalization like the 1930s. It is a world of true global decompression.

Global networks will continue, but only for those who manage to “make it” by the first decades of this early-21st century. Unable to aid the 60% left behind, humanity’s prosperous minority — whether they admit it or not — is increasingly looking to its own defense and preserving the integrity of a smaller system that is still viable. Globalization is now all about a minority living defensively within a seething non-state majority. [continued…]

Michael Vlahos‘ latest book, Fighting Identity: Sacred War and World Change, is reviewed here by Michael Lind.