Richard Feynman’s friend should have known better than to bait the scientist — yet Feynman’s response proves the point: an understanding of the flower’s cellular structure, its evolution, and the evolutionary function of its beauty are all steps away from the experience of beholding a flower’s beauty.

When Feynman says he might not be “quite as refined aesthetically” as his friend, he’s marginalizing the value of perception, yet a flower is irreducibly an object of perception.

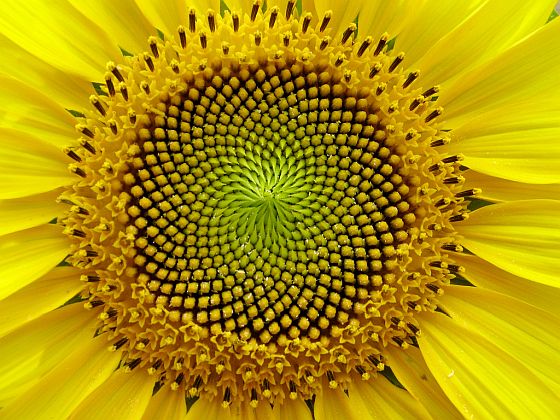

Drill into the structure of a sunflower petal and you may discover the molecular form of the pigments which are the physical substrate of color but you won’t find the essence of yellow since this is only manifest as light, flower, eye, and sentient awareness intersect. Yellow is an experience.

What serves neither art nor science is to treat either as offering a superior method for the appreciation of nature. An artist can profit from a class in cellular biology and scientists can expand their awareness by finding out what it means to open the doors of perception — to be able to see as if seeing the world for the first time.

Science opens doors of exquisite conceptual detail and leads into fascinating fields of exploration, but it doesn’t embrace the full range of the human experience — an experience in which we can be invigorated by losing our selves.

That a scientist and an artist would even be having the argument Feynman describes, speaks above all to a failed educational system.

Who can look carefully at the photograph below and explain why art, poetry, geometry, and biology are not taught in the very same classroom?

We fragment our world into domains of expertise as though no one should be allowed the privilege of exploring the totality.

The failed educational system and fragmentation of our understanding of reality is fundamentally the result of a failed metaphysic. Cartesian dualism is unable to find any coherent intersection between the “material” and the world of experience. Scientists tend to be committed to the belief that only the material is real and that what we call experience is an epiphenomenon. But perhaps they have it exactly backward. Perhaps reality is exhaustively composed of experience, and what we perceive as the “material” is a kind of residual after-effect. Perhaps the “material” is the actual epiphenomenon.

This also sheds light on the crusade of Richard Dawkins, who thinks that his scientific expertise qualifies him to speak on the (non)existence of god. He represents the last ditch stand of monodisciplinarity — someone with the arrogance to dismiss whole other monodisciplines (not to mention the interdisciplines) without even consulting the experts in those fields. Dawkins is what used to be called an “educated barbarian” — and you certainly don’t have to be a bible believer to recognize that. He’s one of those scientists who gives science a bad name.