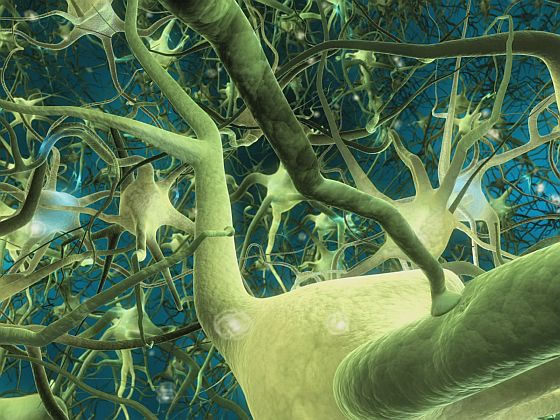

Daniel Dennett says: Each neuron is imprisoned in your brain. I now think of these as cells within cells, as cells within prison cells. Realize that every neuron in your brain, every human cell in your body (leaving aside all the symbionts [such as mitochondria]), is a direct descendent of eukaryotic cells that lived and fended for themselves for about a billion years as free-swimming, free-living little agents. They fended for themselves, and they survived.

They had to develop an awful lot of know-how, a lot of talent, a lot of self-protective talent to do that. When they joined forces into multi-cellular creatures, they gave up a lot of that. They became, in effect, domesticated. They became part of larger, more monolithic organizations. My hunch is that that’s true in general. We don’t have to worry about our muscle cells rebelling against us, or anything like that. When they do, we call it cancer, but in the brain I think that (and this is my wild idea) maybe only in one species, us, and maybe only in the obviously more volatile parts of the brain, the cortical areas, some little switch has been thrown in the genetics that, in effect, makes our neurons a little bit feral, a little bit like what happens when you let sheep or pigs go feral, and they recover their wild talents very fast.

Maybe a lot of the neurons in our brains are not just capable but, if you like, motivated to be more adventurous, more exploratory or risky in the way they comport themselves, in the way they live their lives. They’re struggling amongst themselves with each other for influence, just for staying alive, and there’s competition going on between individual neurons. As soon as that happens, you have room for cooperation to create alliances, and I suspect that a more free-wheeling, anarchic organization is the secret of our greater capacities of creativity, imagination, thinking outside the box and all that, and the price we pay for it is our susceptibility to obsessions, mental illnesses, delusions and smaller problems.

We got risky brains that are much riskier than the brains of other mammals even, even more risky than the brains of chimpanzees, and that this could be partly a matter of a few simple mutations in control genes that release some of the innate competitive talent that is still there in the genomes of the individual neurons. But I don’t think that genetics is the level to explain this. You need culture to explain it.

This, I speculate, is a response to our invention of culture; culture creates a whole new biosphere, in effect, a whole new cultural sphere of activity where there’s opportunities that don’t exist for any other brain tissues in any other creatures, and that this exploration of this space of cultural possibility is what we need to do to explain how the mind works. [Continue reading…]

Brain cells are feral “and the price we pay for it is our susceptibility to obsessions, mental illnesses, delusions and smaller problems.”

Well, that does not connect up — for me — but there is one way that our brains (or is it our societies?) are not adaptable, but themselves prisoners. prisoners of old strategies, of ancient neuroses, if you like.

When the USA went to war with Afghanistan and soon after with Iraq, it did so with almost no discussion, no worrying or thought about consequences, no worry about the $1T that the wars would cost, etc. It was easy, automatic, and fast. VERY FAST. And there was very little, really no, evidence of a threat to Americans requiring all this war-fighting.

By contrast, the threat of climate change (aka global warming) is well documented, backed up by enormous amounts of data and evidence. And the USA and much else of the world has made NO RESPONSE. And spend no money. And we let the tragedy — which is a sort of self immolation, an auto-holocaust — roll over us.

Back to the brain. Our brains (or our societies, as sort of conjoined super-brains) seem hard-wired to respond to immediate threats (however trivial, fake, etc.) but not to respond to distant-seeming threats however huge, actual, etc.

Not feral enough for me.

Interesting comments.

On the idea that feral neurons create a susceptibility to mental problems, I see in this a useful way of framing mental health. The standard Western assumption about mental health is that we start from a balanced baseline and can hope to remain of sound mind if we manage not to suffer the effects of dysfunctional parenting, a toxic environment or other traumatizing events. The image that Dennett evokes however, is that a sound mind is something that needs to be constructed and the framework within which that construction process takes place is culture. As a result, it’s a tall order to expect individuals to develop sound minds inside dysfunctional cultures.

Not responding to global warming = self immolation. That’s an excellent metaphor.

As sense-based creatures we are indeed hard-wired to respond to immediate threats and overlook more distant yet more pervasive danger. Finding a way to culturally mitigate this deficit will require, I believe, a concerted effort in re-education so that people can more readily recognize that our visceral responses primarily have conceptual triggers. We are spellbound by the idea that realism can be equated with materialism and yet in reality the overwhelming majority of our thoughts and feelings arise in response to ideas — ideas about who we are; about how we are perceived by others; about the intentions of others; about the future.

By and large, Americans are spellbound by the idea that the future will be better than the past — even when the immediate future looks bleak, there is always this sense that things will turn around and eventually work out for the best. Climate change? We’ll adapt. We’ll devise technological fixes and create new business opportunities.

In a death-denying culture, it’s very hard to face and explore tragic possibilities.