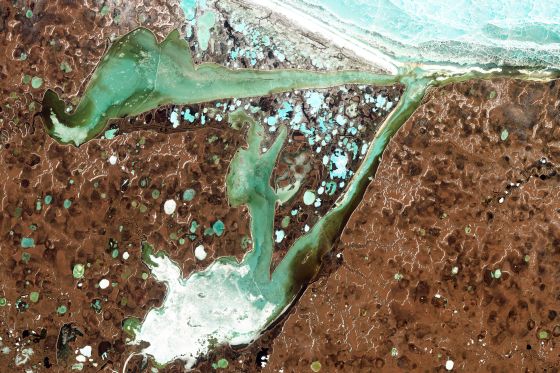

Omulyakhskaya and Khromskaya Bays lie along the northern Siberian coast, where permafrost blankets the land around the bays. Photo: NASA Earth Observatory

Embedded in the mud, glistening green and gold and black, was a butterfly, very beautiful and very dead.

“Not a little thing like that! Not a butterfly!” cried Eckels.

It fell to the floor, an exquisite thing, a small thing that could upset balances and knock down a line of small dominoes and then big dominoes and then gigantic dominoes, all down the years across Time. Eckels’ mind whirled. It couldn’t change things. Killing one butterfly couldn’t be that important! Could it? — Ray Bradbury, A Sound of Thunder, 1952

As one of the massive and probably irreversible consequences of climate change, the melting of the Northern Hemisphere’s permafrost is not an example of the butterfly effect. Yet the discovery of a giant virus which has come back to life after 30,000 years of frozen dormancy, suggests many possibilities including some akin to those envisaged by Ray Bradbury is his famous science fiction story.

Whereas his narrative required that the reader suspend disbelief by entertaining the idea of time travel, the thawing tundra may produce a very real kind of time travel if any viruses or other microbes were to emerge as new invasive species.

Rather than being transported geographically as a result of human activity, these will spring suddenly from a distant past into an environment that may lack necessary evolutionary adaptations to accommodate their presence.

We are assured that Pithovirus sibericum poses no threat to humans — it just attacks amoebas. But our concern shouldn’t be limited to fears about the reemergence of something like an ancient strain of smallpox.

The rebirth of a pathogen that could strike phytoplankton — producers of half the world’s oxygen — would have a devastating impact on the planet.

BBC News reports: The ancient pathogen was discovered buried 30m (100ft) down in the frozen ground.

Called Pithovirus sibericum, it belongs to a class of giant viruses that were discovered 10 years ago.

These are all so large that, unlike other viruses, they can be seen under a microscope. And this one, measuring 1.5 micrometres in length, is the biggest that has ever been found.

The last time it infected anything was more than 30,000 years ago, but in the laboratory it has sprung to life once again.

Tests show that it attacks amoebas, which are single-celled organisms, but does not infect humans or other animals.

Co-author Dr Chantal Abergel, also from the CNRS, said: “It comes into the cell, multiplies and finally kills the cell. It is able to kill the amoeba – but it won’t infect a human cell.”

However, the researchers believe that other more deadly pathogens could be locked in Siberia’s permafrost.

“We are addressing this issue by sequencing the DNA that is present in those layers,” said Dr Abergel.

“This would be the best way to work out what is dangerous in there.”

The researchers say this region is under threat. Since the 1970s, the permafrost has retreated and reduced in thickness, and climate change projections suggest it will decrease further.

It has also become more accessible, and is being eyed for its natural resources.

Prof Claverie warns that exposing the deep layers could expose new viral threats.

He said: “It is a recipe for disaster. If you start having industrial explorations, people will start to move around the deep permafrost layers. Through mining and drilling, those old layers will be penetrated and this is where the danger is coming from.”

He told BBC News that ancient strains of the smallpox virus, which was declared eradicated 30 years ago, could pose a risk. [Continue reading…]