On the tricentenary of Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s birth, Terry Eagleton writes: Much of what one might call the modern sensibility was this thinker’s creation. It is in Rousseau’s writing above all that history begins to turn from upper-class honour to middle-class humanitarianism. Pity, sympathy and compassion lie at the centre of his moral vision. Values associated with the feminine begin to infiltrate social existence as a whole, rather than being confined to the domestic sphere. Gentlemen begin to weep in public, while children are viewed as human beings in their own right rather than defective adults.

Above all, Rousseau is the explorer of that dark continent, the modern self. It is no surprise that he wrote one of the most magnificent autobiographies of all time, his Confessions. Personal experience starts to take on a significance it never had for Plato or Descartes. What matters now is less objective truth than truth-to-self – a passionate conviction that one’s identity is uniquely precious, and that expressing it as freely and richly as possible is a sacred duty. In this belief, Rousseau is a forerunner not only of the Romantics, but of the liberals, existentialists and spiritual individualists of modern times.

It is true that he seems to have held the view that no identity was more uniquely precious than his own. For all his cult of tenderness and affection, Rousseau was not the kind of man with whom one would share one’s picnic. He was the worst kind of hypochondriac – one who really is always ill – and that most dangerous of paranoiacs – one who really is persecuted. Even so, at the heart of an 18th-century Enlightenment devoted to reason and civilisation, this maverick intellectual spoke up for sentiment and nature. He was not, to be sure, as besotted by the notion of the noble savage as some have considered. But he was certainly a scourge of the idea of civilisation, which struck him for the most part as exploitative and corrupt.

In this, he was a notable precursor of Karl Marx. Private property, he wrote, brings war, poverty and class conflict in its wake. It converts “clever usurpation into inalienable right”. Most social order is a fraud perpetrated by the rich on the poor to protect their privileges. The law, he considered, generally backs the strong over the weak; justice is largely a weapon of violence and domination, while culture, science, the arts and religion are harnessed to the task of preserving the status quo. The institution of the state has “bound new fetters on the poor and given new powers to the rich”. For the benefit of a few ambitious men, he comments, “the human race has been subjected to labour, servitude and misery”. [Continue reading…]

Category Archives: Culture

Are we living in sensory overload or sensory poverty?

Diane Ackerman writes: It was a spring morning in upstate New York, one so cold the ground squeaked loudly underfoot as sharp-finned ice crystals rubbed together. The trees looked like gloved hands, fingers frozen open. A crow veered overhead, then landed. As snow flurries began, it leapt into the air, wings aslant, catching the flakes to drink. Or maybe just for fun, since crows can be mighty playful.

Another life form curved into sight down the street: a girl laughing down at her gloveless fingers which were texting on some hand-held device.

This sight is so common that it no longer surprises me, though strolling in a large park one day I was startled by how many people were walking without looking up, or walking in a myopic daze while talking on their “cells,” as we say in shorthand, as if spoken words were paddling through the body from one saltwater lagoon to another.

As a species, we’ve somehow survived large and small ice ages, genetic bottlenecks, plagues, world wars and all manner of natural disasters, but I sometimes wonder if we’ll survive our own ingenuity. At first glance, it seems as if we may be living in sensory overload. The new technology, for all its boons, also bedevils us with alluring distractors, cyberbullies, thought-nabbers, calm-frayers, and a spiky wad of miscellaneous news. Some days it feels like we’re drowning in a twittering bog of information.

But, at exactly the same time, we’re living in sensory poverty, learning about the world without experiencing it up close, right here, right now, in all its messy, majestic, riotous detail. The further we distance ourselves from the spell of the present, explored by our senses, the harder it will be to understand and protect nature’s precarious balance, let alone the balance of our own human nature. [Continue reading…]

Slavoj Žižek: ‘Humanity is OK, but 99% of people are boring idiots’

Decca Aitkenhead interviews Slavoj Žižek: At the risk of upsetting Žižek’s fanatical global following, I would say that a lot of his work is impenetrable. But he writes with exhilarating ambition and his central thesis offers a perspective even his critics would have to concede is thought-provoking. In essence, he argues that nothing is ever what it appears, and contradiction is encoded in almost everything. Most of what we think of as radical or subversive – or even simply ethical – doesn’t actually change anything.

“Like when you buy an organic apple, you’re doing it for ideological reasons, it makes you feel good: ‘I’m doing something for Mother Earth,’ and so on. But in what sense are we engaged? It’s a false engagement. Paradoxically, we do these things to avoid really doing things. It makes you feel good. You recycle, you send £5 a month to some Somali orphan, and you did your duty.” But really, we’ve been tricked into operating safety valves that allow the status quo to survive unchallenged? “Yes, exactly.” The obsession of western liberals with identity politics only distracts from class struggle, and while Žižek doesn’t defend any version of communism ever seen in practice, he remains what he calls a “complicated Marxist” with revolutionary ideals.

To his critics, as one memorably put it, he is the Borat of philosophy, churning out ever more outrageous statements for scandalous effect. “The problem with Hitler was that he was not violent enough,” for example, or “I am not human. I am a monster.” Some dismiss him as a silly controversialist; others fear him as an agitator for neo-Marxist totalitarianism. But since the financial crisis he has been elevated to the status of a global-recession celebrity, drawing crowds of adoring followers who revere him as an intellectual genius. His popularity is just the sort of paradox Žižek delights in because if it were down to him, he says, he would rather not talk to anyone.

You wouldn’t guess so from the energetic flurry of good manners with which he welcomes us, but he’s quick to clarify that his attentiveness is just camouflage for misanthropy. “For me, the idea of hell is the American type of parties. Or, when they ask me to give a talk, and they say something like, ‘After the talk there will just be a small reception’ – I know this is hell. This means all the frustrated idiots, who are not able to ask you a question at the end of the talk, come to you and, usually, they start: ‘Professor Žižek, I know you must be tired, but …’ Well, fuck you. If you know that I am tired, why are you asking me? I’m really more and more becoming Stalinist. Liberals always say about totalitarians that they like humanity, as such, but they have no empathy for concrete people, no? OK, that fits me perfectly. Humanity? Yes, it’s OK – some great talks, some great arts. Concrete people? No, 99% are boring idiots.” [Continue reading…]

Video: The empathic civilization

Video: The land owns us

Bob Randall, a Yankunytjatjara elder from Uluru (Ayer’s Rock) in Australia points out the simple conceit upon which our destructive relationship with this planet is based: the idea that the land on which we depend belongs to us.

Randall describes what in many ways is the universal indigenous experience of a sense of place: that the place in which we emerge into this world is the place to which we belong. It is not a place we go in search of; it is where we are.

The antithesis of this experience is the enterprise of colonization in which “new” land is “discovered” and then claimed in ownership. Embedded in such a claim is a contradiction. The colonizer asserts his entitlement to the land in spite of the fact that his roots lie elsewhere. Unable to trace his ancestral roots within the land he inhabits and unwilling to highlight how far away those roots lead, he constructs a mythological past through which ownership acquires divine authority.

Randall features in this film about the world’s oldest living culture:

Video: Without dog domestication, civilization would not have been possible

The politics of sight and inattention to the unseen

David Sirota writes: Would Americans eat less meat, and would animals be treated more humanely, if slaughterhouses were made with glass walls and we all could see the monstrous killing apparatus at work? This is the query at the heart of Timothy Pachirat’s new book Every Twelve Seconds — the title a reference to the typical slaughterhouse’s cattle-killing rate.

Before you think this is a column merely about food, recognize that Pachirat’s question isn’t (only) about the immorality of the cheeseburger you had for lunch. It’s about the larger phenomenon whereby modern society has reconstructed itself to hide so many horrific consequences from view.

Calling this the “politics of sight,” Pachirat’s blood-soaked experience inside a slaughterhouse spotlights only the most illustrative example of how we’ve divorced ourselves from the means of producing violence—and how, in doing so, we have made it psychologically easier to support such brutality. Sadly, billions of factory-farmed animals dying barbaric deaths are just one subset of casualties in that larger process.

Today, for example, free trade policies that promote offshoring allow Americans to enjoy consumer goods at ultra-low prices without having to see that those low prices represent companies taking advantage of the developing world’s poverty wages, environmental destruction and human rights abuses. A veritable slave may have assembled the iPad you are reading these words on, but thanks to the supply chain’s geography and Apple’s lack of transparency, you can easily avoid dealing with the ethical implications of that reality.

Another example: Many Americans drive gas-guzzling SUVs, proudly slapping patriotic declarations on their bumpers. This seems perfectly reasonable, but only because many either don’t live near polluted oil-drilling sites or don’t have to personally experience the ramifications of our petroleum-focused military policies. Ultimately, by separating the consequences of gas consumption from the driver, we’ve created the psychological conditions for fossil fuel consumption to seem like an honorable statement of strength rather than an endorsement of environmental degradation and war. [Continue reading…]

What did J.D. Salinger, Leo Tolstoy, and Sarah Bernhardt have in common?

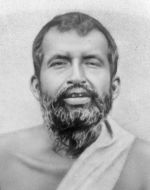

A L Bardach writes: By the late 1960s, the most famous writer in America had become a recluse, having forsaken his dazzling career. Nevertheless, J.D. Salinger often came to Manhattan, staying at his parents’ sprawling apartment on Park Avenue and 91st Street. While he no longer visited with his editors at “The New Yorker,” he was keen to spend time with his spiritual teacher, Swami Nikhilananda, the founder of the Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Center, located, then as now, in a townhouse just three blocks away, at 17 East 94th Street.

Though the iconic author of “The Catcher in the Rye” and “Franny and Zooey” published his last story in 1965, he did not stop writing. From the early 1950s onward, he maintained a lively correspondence with several Vedanta monks and fellow devotees.

After all, the central, guiding light of Salinger’s spiritual quest was the teachings of Vivekananda, the Calcutta-born monk who popularized Vedanta and yoga in the West at the end of the 19th century.

These days yoga is offered up in classes and studios that have become as ubiquitous as Starbucks. Vivekananda would have been puzzled, if not somewhat alarmed. “As soon as I think of myself as a little body,” he warned, “I want to preserve it, protect it, to keep it nice, at the expense of other bodies. Then you and I become separate.” For Vivekananda, who established the first ever Vedanta Center, in Manhattan in 1896, yoga meant just one thing: “the realization of God.”

After an initial dalliance in the late 1940s with Zen—a spiritual path without a God—Salinger discovered Vedanta, which he found infinitely more consoling. “Unlike Zen,” Salinger’s biographer, Kenneth Slawenski, points out, “Vedanta offered a path to a personal relationship with God…[and] a promise that he could obtain a cure for his depression….and find God, and through God, peace.”

Finding peace would, however, be a lifelong battle. In 1975, Salinger wrote to another monk at the New York City center about his own daily struggle, citing a text of the eighth-century Indian mystic Shankara as a cautionary tale: “In the forest-tract of sense pleasures there prowls a huge tiger called the mind. Let good people who have a longing for Liberation never go there.” Salinger wrote, “I suspect that nothing is truer than that,” confessing despondently, “and yet I allow myself to be mauled by that old tiger almost every wakeful minute of my life.”

It was his daily mauling by the “huge tiger” and his dreaded depressions that led Salinger to abandon his literary ambitions in favor of spiritual ones. Salinger—who appears to have had a nervous breakdown of sorts upon his return from the gruesome front lines of World War II—subscribed to Vivekananda’s view of the mind as a drunken monkey who is stung by a scorpion and then consumed by a demon. At the same time, Vivekananda promised hope and solace—writing that the “same mind, when subdued and controlled, becomes a most trusted friend and helper, guaranteeing peace and happiness.” It was precisely the consolation that Salinger so desperately sought. And by 1965 he was ready to renounce his once gritty pursuit of literary celebrity.

Although all but forgotten by America’s 20 million would-be yoginis, clad in their finest Lululemon, Vivekananda was the Bengali monk who introduced the word “yoga” into the national conversation. In 1893, outfitted in a red, flowing turban and yellow robes belted by a scarlet sash, he had delivered a show-stopping speech in Chicago. The event was the tony Parliament of Religions, which had been convened as a spiritual complement to the World’s Fair, showcasing the industrial and technological achievements of the age.

On its opening day, September 11, Vivekananda, who appeared to be meditating onstage, was summoned to speak and did so without notes. “Sisters and Brothers of America,” he began, in a sonorous voice tinged with “a delightful slight Irish brogue,” according to one listener, attributable to his Trinity College–educated professor in India. “It fills my heart with joy unspeakable…”

Then something unprecedented happened, presaging the phenomenon decades later that greeted the Beatles (one of whom, George Harrison, would become a lifelong Vivekananda devotee). The previously sedate crowd of 4,000-plus attendees rose to their feet and wildly cheered the visiting monk, who, having never before addressed a large gathering, was as shocked as his audience. “I thank you in the name of the most ancient order of monks in the world,” he responded, flushed with emotion. “I thank you in the name of the mother of religions, and I thank you in the name of millions and millions of Hindu people of all classes and sects.”

Annie Besant, a British Theosophist and a conference delegate, described Vivekananda’s impact, writing that he was “a striking figure, clad in yellow and orange, shining like the sun of India in the midst of the heavy atmosphere of Chicago…a lion head, piercing eyes, mobile lips, movements swift and abrupt.” The Parliament, she said, was “enraptured; the huge multitude hung upon his words.” When he was done, the convocation rose again and cheered him even more thunderously. Another delegate described “scores of women walking over the benches to get near to him,” prompting one wag to crack wise that if the 30-year-old Vivekananda “can resist that onslaught, [he is] indeed a god.”

“No doubt the vast majority of those present hardly knew why they had been so powerfully moved,” Christopher Isherwood wrote a half century later, surmising that a “strange kind of subconscious telepathy” had infected the hall, beginning with Vivekananda’s first words, which have resonated, for some, long after. Asked about the origins of “My Sweet Lord,” George Harrison replied that “the song really came from Swami Vivekananda, who said, ‘If there is a God, we must see him. And if there is a soul, we must perceive it.’ ”

The teachings of Vedanta are rooted in the Vedas, ancient scriptures going back several thousand years that also inform Buddhism, Hinduism and Jainism. The Vedic texts of the Upanishads enshrine a core belief that God is within and without—that the divine is everywhere. The Bhagavad Gita (Song of God) is another sacred text or gospel, whereas Hinduism is actually a coinage popularized by Vivekananda to describe a faith of diverse and myriad beliefs.

Vivekananda’s genius was to simplify Vedantic thought to a few accessible teachings that Westerners found irresistible. God was not the capricious tyrant in the heavens avowed by Bible-thumpers, but rather a power that resided in the human heart. “Each soul is potentially divine,” he promised. “The goal is to manifest that divinity within by controlling nature, external and internal.” And to close the deal for the fence-sitters, he punched up Vedanta’s embrace of other faiths and their prophets. Christ and Buddha were incarnations of the divine, he said, no less than Krishna and his own teacher, Ramakrishna. [Continue reading…]Ramakrishna

What atheists should take from religion

Alain de Botton, an atheist, argues that rather than mocking religion, atheists and agnostics should steal the best ideas from world religions, such as the methods for building strong communities, overcoming envy, and forging a connection to the natural world. The philosopher essayist discusses his concepts with former seminarian and author Chris Hedges.

Watch a video of their discussion here (C-SPAN Book TV, March 12, 2012).

Borrowed ideas

Casey Schwartz writes: It is the voice inside our head.

The culture to which we belong — whatever it happens to be — fills us with its peculiar inventory. We are shaped by its mandates and its expectations, its anxieties and aspirations, its preferences and aversions. The basic texture of our inner lives is sewn from cultural threads.

And all of this even though we got here, wherever we are, only as a matter of chance.

So Mark Pagel reminds us in his new book, Wired for Culture: Origins of the Human Social Mind.

The culture we inherit, he writes, “is an accident of birth, but it is one to which we show a surprising and sometimes alarming devotion. People will risk their health and well-being, their chances to have children, or even their lives for their culture. People will treat others well or badly merely as an accident of their cultural inheritance.”

How does culture have this kind of grip on us? And what purpose does it serve? These are the central questions of Pagel’s lengthy, multifaceted book.

Pagel, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Reading, belongs to the intellectual hot bed of the edge.org set, a salon of scientific thinkers that has assembled over the years under the auspices of their intriguing host, John Brockman. The ethos of the edge.org crowd is one of unapologetic sophistication; its mission is to bring cutting-edge thinkers together in an ongoing, open-ended conversation, where ideas can beget ideas.

And in his new book, Pagel’s big idea is that culture is the single greatest force for both social and biological change in human history. It has proven itself to be the winning strategy for the survival of our species, bar none. As a result, it has shaped our brains so that they are primed to perpetuate it. [Continue reading…]

Video: Atheism 2.0

The Guardian: “My dad was a slightly stricter version of Richard Dawkins,” says Alain de Botton. “The worldview was that there are idiots out there who believe in Santa Claus and fairies and magic and elves and we’re not joining that nonsense.” In his new book, Religion for Atheists, he recalls his father reducing his sister Miel to tears by “trying to dislodge her modestly held notion that a reclusive god might dwell somewhere in the universe. She was eight at the time.” It’s one of few passages in his unremittingly mellifluous and genteel oeuvre that sticks out with something like anger.

Before the interview, his publicists warned that De Botton didn’t want to talk about Gilbert de Botton, Egyptian-born secular Jew and multimillionaire banker. He was especially keen not to discuss his father’s business dealings and the repeated suggestion that his literary career was bankrolled with daddy’s money.

But asking about De Botton’s father is irresistible because Religion for Atheists is, he readily concedes, an oedipal book. “I’m rebelling,” he says. “I’m trying to find my way back to the babies that have been thrown out with the bathwater.” He’s elsewhere described his father as “a cruel tyrant as a domestic figure, hugely overbearing”. He was also surely crushingly impressive – the former head of Rothschild Bank who established Global Asset Management in 1983 with £1m capital and sold it to UBS in 1999 for £420m, a collector of late Picassos, the austere figure depicted in portraits by both Lucian Freud and Francis Bacon and an atheist who thrived without religion’s crutch.

“He was extreme. I think it was a generational thing.” And yet Gilbert, who died in 2000, now lies beneath a Hebrew headstone in a Jewish cemetery in Willesden, north-west London because, as his son writes pointedly, “he had, intriguingly, omitted to make more secular arrangements”. Disappointingly, Alain doesn’t explore in book or interview what intrigued him about that omission.

Instead, he connects his father’s militant atheism to the affliction that he reckons made Dawkins and Christopher Hitchens so caustic in their bestselling attacks on religion. “I’ve got a generational theory about this. Particularly if you’re a man over 55 or so, perhaps something bad happened to you at the hands of religion – you came across a corrupt priest, you were bored at school, your parents forced it down your throat. Few of the younger generation feel that way. By the time I came around – I’m 42 – religion was a joke.

“I don’t think I would have written this book if I’d grown up in Saudi Arabia as a woman. It’s a European book in the sense that we’re living in a society where religion is on the back foot. It rarely intruded on my life.”

This isn’t quite true. In his mid 20s, De Botton had a crisis of faithlessness when exposed to Bach’s cantatas, Bellini’s Madonnas and Zen architecture. What was the crisis about? “It was guilt about my father. I was disturbed by the intensity of the feeling. Bach was moving, but not just because of music but because this guy was talking in a tremulous voice about death. Secular culture tells us to respect Bach, but it doesn’t tell us that we’re going to be moved. I felt like I might go to the other side.”

He didn’t. Rather, in Religion for Atheists, he writes as a non-believer cherry-picking the world’s religions. “I guess my insight was: ‘What is there here that’s useful, that we can steal?'” He admires 18th-century Jesuits. “They wanted to put a Jesuit priest into every aristocratic family in Europe because they’d get to eat with the family and teach the children. That’s a fantastic idea.” It’s tempting to think of De Botton as a latter-day Jesuit seeking to install his books in every home in order to make us, even if faithless, good. “Secular thinkers have a separation between thinking and doing. They don’t have a grasp of the balance sheet. The doers are selling us potted plants and pizzas while the thinkers are a little bit unworldly. Religions both think and do.”

The paralyzing effect of choice

Professor Renata Salecl explores the paralyzing anxiety and dissatisfaction surrounding limitless choice. Her unedited, unanimated talk can be viewed here.

Schools in the Texas police state

Chris McGreal reports: The charge on the police docket was “disrupting class”. But that’s not how 12-year-old Sarah Bustamantes saw her arrest for spraying two bursts of perfume on her neck in class because other children were bullying her with taunts of “you smell”.

“I’m weird. Other kids don’t like me,” said Sarah, who has been diagnosed with attention-deficit and bipolar disorders and who is conscious of being overweight. “They were saying a lot of rude things to me. Just picking on me. So I sprayed myself with perfume. Then they said: ‘Put that away, that’s the most terrible smell I’ve ever smelled.’ Then the teacher called the police.”

The policeman didn’t have far to come. He patrols the corridors of Sarah’s school, Fulmore Middle in Austin, Texas. Like hundreds of schools in the state, and across large parts of the rest of the US, Fulmore Middle has its own police force with officers in uniform who carry guns to keep order in the canteens, playgrounds and lessons. Sarah was taken from class, charged with a criminal misdemeanour and ordered to appear in court.

Each day, hundreds of schoolchildren appear before courts in Texas charged with offences such as swearing, misbehaving on the school bus or getting in to a punch-up in the playground. Children have been arrested for possessing cigarettes, wearing “inappropriate” clothes and being late for school.

In 2010, the police gave close to 300,000 “Class C misdemeanour” tickets to children as young as six in Texas for offences in and out of school, which result in fines, community service and even prison time. What was once handled with a telling-off by the teacher or a call to parents can now result in arrest and a record that may cost a young person a place in college or a job years later.

Lessons of the Luddites

Eliane Glaser writes: Two hundred years ago this month, groups of artisan cloth workers began to assemble at night on the moors around towns in Nottinghamshire. Proclaiming allegiance to the mythical King Ludd of Sherwood Forest, and sometimes subversively cross-dressed in frocks and bonnets, the Luddites organised machine-wrecking raids on textile factories that quickly spread across the north of England. The government mobilised the army and made frame breaking a capital offence: the uprisings were subdued by the summer of 1812.

Contrary to modern assumptions, the Luddites were not opposed to technology itself. They were opposed to the particular way it was being applied. After all, stocking frames had been around for 200 years by the time the Luddites came along, and they weren’t the first to smash them up. Their protest was specifically aimed at a new class of manufacturers who were aggressively undermining wages, dismantling workers’ rights and imposing a corrosive early form of free trade. To prove it, they selectively destroyed the machines owned by factory managers who were undercutting prices, leaving the other machines intact.

The original Luddites enjoyed strong local backing as well as high-profile support from Lord Byron and Mary Shelley, whose novel Frankenstein alludes to the industrial revolution’s dark side. But in the digital age, Luddism as a position is barely tenable. Just as we assume that the original Luddites were simply technophobes, it’s become unthinkable to countenance any broader political objections to contemporary technology’s direction of travel.

The promoters of internet technology combine visionary enthusiasm and like-it-or-not realism. So dissent is dismissed as either an irrational rejection of progress or a refusal to face the inevitable. It’s the realism that’s particularly hard to counter; the notion that technology is an unstoppable and non-negotiable force entirely separate from human agency. There’s not much time for political critique if you’re constantly being told that “the world is changing fast and you have to keep up”. Which is a bit rich given that politics infuses the arguments of even technology’s purest advocates.

As Slavoj Žižek has noted, the language of internet advocacy – phrases like “the unlimited flow of information” and “the marketplace of ideas” – mirrors the language of free-market economics. But techno-prophets also use the lingo of leftwing revolution. It’s there in books such as James Surowiecki’s The Wisdom of Crowds and Clay Shirky’s Here Comes Everybody, and in Vodafone’s slogan, “Power to You”; in the notion that blogs, Twitter and newspaper comment threads create a level playing field in the public debate; and it’s there in the countless magazine features about how the internet fosters grassroots protest, places the tools of cultural production in amateurs’ hands, and allows the little guy immediate access to information that keeps political leaders on their toes. This is not Adam Smith, it’s Marx and Mao.

In fact, both rhetorics – of the free market and of bottom-up emancipation – serve to conceal the rise of crony capitalism and the concentration of power and money at the top. Google is busily acquiring “all the world’s information”. Facebook is gathering our personal data for the coming world of personalised advertising. Amazon is monopolising the book trade. The abandonment of net neutrality means corporate control of the web. Once all our books, music, pictures and information are stored in the cloud, it will be owned by a handful of conglomerates.

The evolutionary roots of collective intelligence

Big Think: For much of the 20th century, social scientists assumed that competition and strife were the natural order of things, as ingrained as the need for food and shelter. The world would be a better place if we could all just be a little more like John Wayne, the thinking went.

Now researchers are beginning to see teamwork as a biological imperative, present in even the most basic life forms on Earth. And it’s not just about fairness, or the strong lifting up the weak. Collective problem-solving is simply more efficient than rugged individualism.

Enslaved by economics — the story we live by

Maria Popova reviews Monoculture: How One Story Is Changing Everything:

“The universe is made of stories, not atoms,” poet Muriel Rukeyser famously proclaimed. The stories we tell ourselves and each other are how we make sense of the world and our place in it. Some stories become so sticky, so pervasive that we internalize them to a point where we no longer see their storiness — they become not one of many lenses on reality, but reality itself. And breaking through them becomes exponentially difficult because part of our shared human downfall is our ego’s blind conviction that we’re autonomous agents acting solely on our own volition, rolling our eyes at any insinuation we might be influenced by something external to our selves. Yet we are — we’re infinitely influenced by these stories we’ve come to internalize, stories we’ve heard and repeated so many times they’ve become the invisible underpinning of our entire lived experience.

That’s exactly what F. S. Michaels explores in Monoculture: How One Story Is Changing Everything — a provocative investigation of the dominant story of our time and how it’s shaping six key areas of our lives: our work, our relationships with others and the natural world, our education, our physical and mental health, our communities, and our creativity.

The governing pattern a culture obeys is a master story– one narrative in society that takes over the others, shrinking diversity and forming a monoculture. When you’re inside a master story at a particular time in history, you tend to accept its definition of reality. You unconsciously believe and act on certain things, and disbelieve and fail to act on other things. That’s the power of the monoculture; it’s able to direct us without us knowing too much about it.” ~ F. S. Michaels

During the Middle Ages, the dominant monoculture was one of religion and superstition. When Galileo challenged the Catholic Church’s geocentricity with his heliocentric model of the universe, he was accused of heresy and punished accordingly, but he did spark the drawn of the next monoculture, which reached a tipping point in the seventeenth century as humanity came to believe the world was fully knowable and discoverable through science, machines and mathematics — the scientific monoculture was born.

Ours, Micheals demonstrates, is a monoculture shaped by economic values and assumptions, and it shapes everything from the obvious things (our consumer habits, the music we listen to, the clothes we wear) to the less obvious and more uncomfortable to relinquish the belief of autonomy over (our relationships, our religion, our appreciation of art).

Does Islam stand against science?

Steve Paulson writes:

We may think the charged relationship between science and religion is mainly a problem for Christian fundamentalists, but modern science is also under fire in the Muslim world. Islamic creationist movements are gaining momentum, and growing numbers of Muslims now look to the Quran itself for revelations about science.

Science in Muslim societies already lags far behind the scientific achievements of the West, but what adds a fair amount of contemporary angst is that Islamic civilization was once the unrivaled center of science and philosophy. What’s more, Islam’s “golden age” flourished while Europe was mired in the Dark Ages.

This history raises a troubling question: What caused the decline of science in the Muslim world?

Now, a small but emerging group of scholars is taking a new look at the relationship between Islam and science. Many have personal roots in Muslim or Arab cultures. While some are observant Muslims and others are nonbelievers, they share a commitment to speak out—in books, blogs, and public lectures—in defense of science. If they have a common message, it’s the conviction that there’s no inherent conflict between Islam and science.

The dominant culture is killing the planet

Chilean economist Manfred Max-Neef and poet-philosopher of the ecological movement, Derrick Jensen on Democracy Now!