Kamila Shamsie writes: Malala Yousafzai says she’s lost herself. “In Swat [district], I studied in the same school for 10 years and there I was just considered to be Malala. Here I’m famous, here people think of me as the girl who was shot by the Taliban. The real Malala is gone somewhere, and I can’t find her.”

We are sitting in a boardroom on the seventh floor of the new Birmingham library, the glass walls allowing us a view of a city draped in mist, a sharp contrast to the “paradise” of Swat, with its tall mountains and clear rivers which Malala recalls wistfully. It should be desperately sad but the world’s most famous 16-year-old makes it difficult for you to feel sorry for her. In part, it is because she is so poised, in a way that suggests an enviable self-assurance rather than an overconstructed persona. But more than that, it is to do with how much of her conversation is punctuated by laughter.

The laughter takes many forms: self-deprecating when I ask her why she thinks the Taliban feel threatened by her; delighted when she talks of Skyping her best friend, Muniba, to get the latest gossip from her old school; wry when she recalls a Taliban commander’s advice that she return to Pakistan and enter a madrassa; giggly when she talks about her favourite cricketers (“Shahid Afridi, of course, and I also like Shane Watson”). And it’s at its most full-throated when she is teasing her father, who is present for part of our interview. It happens during a conversation about her mother: “She loves my father,” Malala says. Then, lowering her voice, she adds: “They had a love marriage.” Her father, involved in making tea for Malala and me, looks up. “Hmmm? Are you sure?” he says, mock-stern. “Learn from your parents!” Malala says to me, and bursts into laughter.

Learning from her parents is something Malala knows a great deal about. Her mother was never formally educated and an awareness of the constraints this placed on her life have made her a great supporter of Malala and her father in their campaign against the Taliban’s attempts to stop female education. One of the more moving details in I Am Malala, the memoir Malala has written with the journalist Christina Lamb, is that her mother was due to start learning to read and write on the day Malala was shot – 9 October 2012. When I suggest that Malala’s campaign for female education may have played a role in encouraging her mother, she says: “That might be.” But she is much happier giving credit to her mother’s determined character, and the example provided by her father, Ziauddin, who long ago set up a school where girls could study as well as boys, in a part of the world where the gender gap in education is vast.

It is hard to refrain from asking Ziauddin Yousafzai the “do you wish you hadn’t …?” question about his daughter, whose passion for reform clearly owes a lot to the desire to emulate her education-activist father. But it’s a cruel question, and unfair, too, given my own inability to work out what constitutes responsible parenting in a world where girls are told that the safest way to live is to stay away from school, and preferably disappear entirely.

It is perhaps because of criticism levelled at her father that Malala mentions more than once in her book that no one believed the Taliban would target a schoolgirl, even if that schoolgirl had been speaking and writing against the Taliban’s ban on female education since the age of 12. If any member of the family was believed to be in danger, it was Ziauddin Yousafzai, as much a part of the campaign as his daughter. And it was the daughter who urged the father to keep on when he suggested they both “go into hibernation” after receiving particularly worrisome threats. The most interesting detail to emerge about Ziauddin from his daughter’s book is his own early flirtation with militancy. He was only 12 years old when Sufi Mohammad, who would later be a leading figure among the extremists in Swat, came to his village to recruit young boys to join the jihad against the Soviets in Afghanistan. Although Ziauddin was too young to fight then, within a few years he was preparing to become a jihadi, and praying for martyrdom. He later came to recognise what he experienced as brainwashing – and was saved from it by his questioning mind and the influence of his future brother-in-law, a secular nationalist.

The information about her father’s semi-brainwashing forms an interesting backdrop to Malala’s comments when I ask if she ever wonders about the man who tried to kill her on her way back from school that day in October last year, and why his hands were shaking as he held the gun – a detail she has picked up from the girls in the school bus with her at the time; she herself has no memory of the shooting. There is no trace of rancour in her voice when she says: “He was young, in his 20s … he was quite young, we may call him a boy. And it’s hard to have a gun and kill people. Maybe that’s why his hand was shaking. Maybe he didn’t know if he could do it. But people are brainwashed. That’s why they do things like suicide attacks and killing people. I can’t imagine it – that boy who shot me, I can’t imagine hurting him even with a needle. I believe in peace. I believe in mercy.” [Continue reading…]

Category Archives: Taliban

Taliban advances on diplomatic front

Daily Beast reports: Nearly one year after announcing it was “suspending all dialogue” with the U.S. over its “ever-changing position,” the Taliban seem keen to enter into preliminary peace talks once again. The Taliban’s sudden desire to reopen talks with the U.S., and perhaps even with the government of President Hamid Karzai, whom the insurgency has consistently denounced as an unrepresentative American puppet, represents a sudden and dramatic U-turn. Over the past month a number of high-ranking Taliban officials have been traveling between their Pakistani safe haven in Quetta and the Gulf state of Qatar, the scene of the previous talks, apparently in an effort to set up shop and to rekindle the dialogue. “Our leaders are now regularly running between Qatar and Quetta,” says Zabihullah, a Taliban political operative whose information has proved reliable in the past.

Amir Khan Motaqi, the important head of the insurgency’s propaganda office recently made the trip, and reported back to Quetta. Abdul Wasi, the former deputy head of the Taliban’s Red Crescent Society, who was released from an Afghan jail one year ago, arrived in Qatar last month in order to set up a permanent office for negotiations. Several Taliban officials who are now in Qatar living in guesthouses are in the process of moving into apartments and houses. Some are bringing their families.

According to two high-ranking Taliban, the family of deceased Defense Minister Mullah Obaidullah Akhund, who died in Pakistani captivity nearly three years ago, is being moved from Karachi to Qatar, along with the family of former insurgent spokesman Ustad Yasir, who is still imprisoned in Pakistan, in an effort to begin building a small Taliban-friendly community in Qatar and receive released insurgent prisoners.

All this recent traffic between Quetta and Qatar, with Pakistan’s approval and assistance, shows that the growing Taliban delegation is no longer isolated from the leadership council in Quetta as it was in the past. Over the past two years, timely communication between the negotiating team in Qatar and the ruling shura, or council, in Quetta was practically nonexistent.

Not anymore.

“The communication gap between Quetta and Qatar has been removed,” says a former senior Taliban minister. [Continue reading…]

Taliban are fighting a political war while the U.S. is still fighting a tactical military war

Rajiv Chandrasekaran reports: As U.S. and NATO forces have evicted insurgents from a broad swath of southern Afghanistan, senior Taliban commanders have shifted toward a new battlefield strategy, one less focused on reclaiming lost territory and more on winning the next phase of the 11-year-old war.

U.S. military and intelligence officials believe that Taliban commanders, driven by a combination of desperation and savvy, have started assigning more of their suicide fighters to conduct audacious attacks against prominent targets across the country, including the U.S. Embassy and well-fortified NATO bases.

Insurgent leaders, they say, have redoubled a campaign to assassinate key Afghan government and security officials who are likely to play leadership roles in the country once foreign troops depart. And by happenstance or meticulous planning — U.S. military officials are not sure which — the Taliban has managed to kill numerous Western troops by joining the ranks of the Afghan army.

“The Taliban are fighting a political war while the United States and its allies are still fighting a tactical military war,” said Joshua Foust, a former U.S. intelligence analyst who has worked in Afghanistan and is now a fellow with the American Security Project. “We remain focused on terrain. They are focused on attacking the transition process and seizing the narrative of victory.”

The impact of the strategic shift, which has occurred gradually over the past year, has been profound. The high-profile assaults and assassinations have prompted new doubts among Afghans about the ability of their government and security forces to keep the insurgents at bay once NATO’s combat mission ends in 2014. The infiltration of the security forces led the top allied operational commander in Kabul on Monday to order extraordinary new restrictions on joint patrols and other missions, a move that strikes at the heart of the U.S. and NATO strategy to operate in closer partnership with Afghan soldiers. [Continue reading…]

Why it’s time for talks with the Taliban

Matt Waldman writes: We should welcome the news that the Taliban are reportedly open to the idea of negotiating a general ceasefire and even a peace settlement. The peace process in Afghanistan is at risk from spoilers on all sides and fraught with challenges. But we owe it to the Afghan people, and to all those who have suffered in the conflict, to give it a try.

It would be a grave mistake to assume the Taliban would only settle for absolute power. Taliban leaders know they stand no chance of seizing power now or in the near future. They know that even coming close would reinvigorate and potentially augment the coalition of forces ranged against them. That could trigger a civil war, which they are anxious to avoid. Even if they could seize power, they would be pounded by drones, ostracised and dependent on Pakistan. The leadership craves the opposite: safety, recognition and independence.

The Taliban rose to power in the 1990s, promising to bring order in place of turmoil. But since 2001, the expectations of ordinary Afghans have changed. They not only want order and justice but reliable public services, basic freedoms and a say over their own affairs. Antediluvian theocracy has had its day, and thinking Talibs know it.

The Arab awakening has not gone unheeded. A Taliban think-piece leaked last year asked what kind of elections they should support and how the government should meet the people’s needs. They yearn to be taken seriously as a credible, national political force. [Continue reading…]

Afghanistan’s peace hopes may rest on Taliban captive

Reuters reports: In the cloistered circles of the Taliban high command, Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar had no equal.

As military chief of the hardline Islamic movement that once ruled Afghanistan and was ousted by a U.S.-led alliance, he oversaw the campaign of ambushes and roadside bombings that proved his fighters could threaten the most advanced armies.

When the talismanic leader was caught in the Pakistani city of Karachi in 2010, some Afghan officials hoped the magnetism he forged in war would persuade his former comrades to start talking peace. Indeed, news that Islamabad had allowed Afghan officials to visit Baradar two months ago sparked speculation in both countries of the prospects for a settlement.

Instead, Pakistan’s refusal to hand him over to Afghanistan symbolises one of the biggest obstacles to negotiations: a legacy of bone-deep suspicion dividing the neighbours.

Afghanistan fears that Pakistan is only pretending to support dialogue while its intelligence agencies harbour Taliban leaders to project influence across their shared frontier.

Any move to repatriate Baradar would raise Afghan hopes that Pakistan is willing to play a genuinely constructive role and open the door to other prominent insurgents.

“Releasing Mullah Baradar would encourage other Taliban leaders to embrace reconciliation,” Ismail Qasemyar, an adviser to Afghanistan’s High Peace Council, told Reuters. “It would be a huge symbolic step.” [Continue reading…]

Taliban commander: we cannot win war and al-Qaida is a ‘plague’

Julian Borger reports: One of the Taliban’s most senior commanders has admitted the insurgents cannot win the war in Afghanistan and that capturing Kabul is “a very distant prospect”, obliging them to seek a settlement with other political forces in the country.

In a startlingly frank interview in Thursday’s New Statesman, the commander – described as a Taliban veteran, a confidant of the leadership, and a former Guantánamo inmate – also uses the strongest language yet from a senior figure to distance the Afghan rebels from al-Qaida.

“At least 70% of the Taliban are angry at al-Qaida. Our people consider al-Qaida to be a plague that was sent down to us by the heavens,” the commander says. “To tell the truth, I was relieved at the death of Osama [bin Laden]. Through his policies, he destroyed Afghanistan. If he really believed in jihad he should have gone to Saudi Arabia and done jihad there, rather than wrecking our country.”

The New Statesman does not identify the Taliban commander, referring to him only as Mawlvi but the interview was conducted by Michael Semple, a former UN envoy to Kabul during the Taliban era who has maintained contacts with members of its leadership, and served on occasion as a diplomatic back-channel to the insurgents.

Semple, who is now at the Carr Centre for Human Rights Policy at Harvard, said the commander’s identity had to be protected because the Taliban was highly sensitive about unauthorised pronouncements on the movement’s behalf, but he added there was no doubt about Mawlvi’s role within the movement.

“I maintain dialogue over time rather than have one-off contacts so I know who Mawlvi is and I know everyone he is talking to,” he said. [Continue reading…]

Taliban praise India for resisting Afghan entanglement

Reuters reports: India has done well to resist U.S. calls for greater involvement in Afghanistan, the Taliban said in a rare direct comment about one of the strongest opponents of the hardline Islamist group that was ousted from power in 2001.

The Taliban also said they won’t let Afghanistan be used as a base against another country, addressing fears in New Delhi that Pakistan-based anti-India militants may become more emboldened if the Taliban return to power.

The Afghan Taliban have longstanding ties to Pakistan and striking a softer tone towards its arch rival India could be a sign of a more independent course.

Direct talks with the United States – which have since been suspended – and an agreement to open a Taliban office in Qatar to conduct formal peace talks have been seen as signs of a more assertive stance.

U.S. Defense Secretary Leon Panetta this month encouraged India to take a more active role in Afghanistan as most foreign combat troops leave in 2014. The Taliban said Panetta had failed.

“He spent three days in India to transfer the heavy burden to their shoulders, to find an exit, and to flee from Afghanistan,” the group said on its English website.

“Some reliable media sources said that the Indian authorities did not pay heed to (U.S.) demands and showed their reservations, because the Indians know or they should know that the Americans are grinding their own axe.”

There had been no assurance for the Americans, Taliban spokesman Zabihullah Mujahid told Reuters on Sunday.

“It shows that India understands the facts,” he said.

India is one of the biggest donors in Afghanistan, spending about $2 billion on projects ranging from the construction of highways to the building of the Afghan parliament. It has also won an iron ore concession in a $11 billion investment.

But New Delhi has avoided involvement in bolstering Afghan security, except for running courses for small groups of Afghan army officers at military institutions in India.

“No doubt that India is a significant country in the region, but is also worth mentioning that they have full information about Afghanistan because they know each other very well in the long history,” the Taliban said.

“They are aware of the Afghan aspirations, creeds and love for freedom. It is totally illogical they should plunge their nation into a calamity just for the American pleasure.” [Continue reading…]

The great Taliban jailbreak

Luke Mogelson writes: When the stranger unbolted the cell door and whispered for them to hurry, Rahim assumed that somewhere in the prison a fight must have broken out. It was the middle of the night, and normally the heavy metal door remained locked until the morning call to prayer. For the past five months, Rahim had shared this cell, in Kandahar’s Sarposa Prison, with five other captured insurgents, two of whom he’d fought alongside in the fiercely contested district of Panjwai. Now, from where they lay on old blankets and cushions on the floor, all five gazed uncertainly at the man standing in their doorway. “We are your friends,” the man said. “There is a tunnel over here. Come quickly and get inside it.”

Rahim and his cellmates stepped into the prison’s dimly lit lime green corridor. At the passageway’s far end, a metal gate sealed the cell-block entrance. Every ten feet or so, solid black doors led to more communal cells. Nearly 500 Taliban occupied this part of Sarposa, called the political block. Some were military commanders and shadow-government officials, others hardened foot soldiers and young recruits. Their arrests represented years of effort by coalition forces to quell a resuscitated insurgency and impose some semblance of law in one of the least stable regions in Afghanistan. Following the stranger down the long hall, Rahim noticed that most of the cells were now empty.

The group made its way quietly but without too much concern for the guards; Sarposa’s officers seldom patrolled the political block. Once in the morning and once in the evening they came to take attendance; otherwise, the Taliban were left to care for themselves. Within the block’s three contiguous wings, a council of elders resolved disputes, prisoners knitted blankets and clothes for those lacking them, and in an enclosed courtyard a detained imam led prayers five times a day. The cells themselves were lavishly furnished with comfort items delivered in large plastic bags by visitors every weekend—cushions, blankets, rugs, electric fans, and lamps. Periodic security checks invariably uncovered mobile phones secreted in the floors and walls. Since the Taliban consider music un-Islamic, radios were nonexistent. Instead, for amusement, inmates flipped over metal soup bowls and beat them in time with religious chants. As Rahim and his cellmates moved down the corridor, their footfalls were mu±ed by such a drumming.

Near the gated entrance at the end of the corridor, the stranger ushered the group into a cell adorned with old maps, embroidered tapestries, and a mirror hanging from a coatrack, decorated with an etching of an AK-47. A blue carpet had been pulled back from one corner of the cell to reveal a triangular hole in the floor. Rahim approached the jagged opening and peered inside. The striated walls tunneled down through half a foot of concrete, through an equally thin layer of foundational stone, and finally through some six feet of brown earth. Several prisoners gathered at its edge. Some were young fighters; a few were geriatrics or amputees. Rahim was in his early twenties but had lost his left leg a year earlier to an IED and now used a prosthesis. He watched an old man toss his crutches aside and lower himself into the floor. Rahim did the same.

The dirt below was dry and soft. It was so crowded that when Rahim fell to his knees and started to crawl, he bumped into the man ahead of him. As he inched forward, another prisoner jumped into the hole behind him. On all fours, his back scraping against the ceiling, Rahim wormed his way forward. Whoever had burrowed the passage had installed a series of light bulbs that hung from an electrical cord. But by now many of the bulbs had shattered, broken by passing prisoners, and pieces of glass littered the tunnel floor. After a few hundred feet, it was almost completely dark. [Continue reading…]

Video: U.S. considers prisoner tranfers for Taliban peace deal

Video: Is Pakistan backing the Taliban?

Taliban make formal declaration of victory

The New York Times reports: Mullah Muhammad Omar, the Taliban’s one-eyed leader, seems to have taken a page from George W. Bush’s playbook.

Just as the former president declared “mission accomplished” in Iraq years before the war there ended, the Taliban made their own victory declaration this weekend, even though roughly 130,000 coalition troops were still fighting in Afghanistan — and keeping the Afghan government firmly in power.

No matter, suggested the Taliban, which calls itself the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, in a statement bluntly titled: “Formal Proclamation of Islamic Emirate’s Victory.” The American push to open talks is proof that the insurgents are winning, the Taliban reasoned.

“It is but sheer determination, religious and ideological adherence and unequalled sacrifices displayed by true Afghan Mujahid nation for the last decade that today regional and world powers are after to reach mutual understanding about the country,” the statement said in the Taliban’s typically fractured English.

The coalition declined to comment on the Taliban’s statement.

Most American and Afghan officials would surely dispute the Taliban’s logic. But taken as a statement of intent, the Taliban’s declaration offers an instructive glimpse into their thinking. For them, a seat across the table from the Americans – and, if a settlement is reached, a formal role in the Afghan government — may be the victory they’ve been fighting for.

Dial 1 to speak to the Taliban

The Economist‘s Asia blog considers the prospects for peace in Afghanistan now that the Taliban has an official address — a political office in Qatar.

Peace with the Taliban has three main actors and a large unsupporting cast. The opening of a Taliban office in Qatar suggests a change of direction from one of the essential players, Pakistan. Previous attempts by senior Talibs to talk to the Americans and the Afghan government have been nixed by Pakistan, anxious to maintain a stranglehold over the Taliban movement and ensure that any peace process worked in Islamabad’s interests. Just last year when the media reported that Tayeb Agha, the former secretary to the Taliban supreme leader Mullah Omar, had been holding secret talks with German and American diplomats, his entire family in Pakistan was promptly put under house arrest.

The latest round of talks that led to the Qatar breakthrough was once again led by Mr Agha. Western experts in Kabul think the plan would never have got this far without a degree of Pakistani involvement, which in turn implies a measure of support from Islamabad.

America, the second big player, hopes that by dangling the possibility of releasing senior Taliban prisoners held in Guantanamo in exchange for a ceasefire, it can nurture a serious peace process. At the same time, American diplomats are talking tough, trying to convince the Taliban that they cannot win in the long-run, and have no chance of sweeping back to power and re-establishing their old regime.

For those Taliban who pay attention to geopolitics, the argument is convincing. First, a little background. The circumstances that saw the Taliban rise to power in 1996 are unlikely to be repeated. In those days America had withdrawn from Afghan affairs, whilst the Soviet Union no longer existed. Without the involvement of the two great superpowers, the field was left clear for Pakistan.

Afghanistan’s neighbour had long been anxious to see a weak, pliant regime in Kabul that would be hostile to India and not assert claims to territory ceded in 1893, under British pressure, to what is now Pakistan. Pakistan eventually got everything it wanted by throwing support behind an obscure bunch of pious former mujahideen led by Mr Omar, back when he was just a one-eyed mullah living in the rural outskirts of Kandahar. Pakistan’s infamous Inter-Services Intelligence agency (ISI) helped put these religious “students”, or Taliban, in power by giving them military support, as well as paying-off power brokers who stood in their way.

Fast forward to today and things look far less congenial for the Taliban. Despite American weariness at the high cost in lives and treasure, it remains unlikely that Afghanistan will be abandoned again. Today’s insurgency remains a phenomenon restricted to just one ethnic group, the Pashtuns. Consequently it lacks the nationwide appeal that the mujahideen enjoyed in the 1980s. In military terms the insurgents have been clobbered in swathes of the south. They are only really vigorous in a relatively small number of districts. Also, despite the notorious short comings of the Karzai administration, the Afghan state continues to strengthen. In such circumstances it would make sense for the insurgents to make a deal sooner rather than later.

Taliban leaders held at Guantánamo Bay to be released in peace talks deal

The Guardian reports: The US has agreed in principle to release high-ranking Taliban officials from Guantánamo Bay in return for the Afghan insurgents’ agreement to open a political office for peace negotiations in Qatar, the Guardian has learned.

According to sources familiar with the talks in the US and in Afghanistan, the handful of Taliban figures will include Mullah Khair Khowa, a former interior minister, and Noorullah Noori, a former governor in northern Afghanistan.

More controversially, the Taliban are demanding the release of the former army commander Mullah Fazl Akhund. Washington is reported to be considering formally handing him over to the custody of another country, possibly Qatar.

The releases would be to reciprocate for Tuesday’s announcement from the Taliban that they are prepared to open a political office in Qatar to conduct peace negotiations “with the international community” – the most significant political breakthrough in ten years of the Afghan conflict.

The Taliban are holding just one American soldier, Bowe Bergdahl, a 25-year-old sergeant captured in June 2009, but it is not clear whether he would be freed as part of the deal.

“To take this step, the [Obama] administration have to have sufficient confidence that the Taliban are going to reciprocate,” said Vali Nasr, who was an Obama administration adviser on the Afghan peace process until last year. “It is going to be really risky. Guantánamo is a very sensitive issue politically.”

Pakistani death squads go after informants to U.S. drone program

The Los Angeles Times reports: The death squad shows up in uniform: black masks and tunics with the name of the group, Khorasan Mujahedin, scrawled across the back in Urdu.

Pulling up in caravans of Toyota Corolla hatchbacks, dozens of them seal off mud-hut villages near the Afghan border, and then scour markets and homes in search of tribesmen they suspect of helping to identify targets for the armed U.S. drones that routinely buzz overhead.

Once they’ve snatched their suspect, they don’t speed off, villagers say. Instead, the caravan leaves slowly, a trademark gesture meant to convey that they expect no retaliation.

Militant groups lack the ability to bring down the drones, which have killed senior Al Qaeda and Taliban commanders as well as many foot soldiers. Instead, a collection of them have banded together to form Khorasan Mujahedin in the North Waziristan tribal region to hunt for those who sell information about the location of militants and their safe houses.

Pakistani officials and tribal elders maintain that most of those who are abducted this way are innocent, but after being beaten, burned with irons or scalded with boiling water, almost all eventually “confess.” And few ever come back.

One who did was a shop owner in the town of Mir Ali, a well-known hub of militant activity.

A band of Khorasan gunmen strode up to the shop owner one afternoon last fall, threw him into one of their cars and drove away, said a relative who spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of reprisal. They took him to a safe house being used as a lockup for others the group suspected of spying for the drone program.

For the next eight weeks, they bludgeoned him with sticks, trying to get him to confess that he was a drone spy. He wasn’t, said the relative. Unable to determine whether he was guilty, his captors released him to another militant group, which set him free 10 days later.

“In the sky there are drones, and on the ground there’s Khorasan Mujahedin,” said the relative. “Villagers are extremely terrorized. Whenever there’s a drone strike, within 24 hours Khorasan Mujahedin comes in and takes people away.”

Most of them are killed. The group, named after an early Islamic empire that covered a large part of Central Asia, dumps the bodies on roadsides, usually with scraps of paper attached to their bloodied tunics that warn others of the consequences of spying for the U.S. Executions are often videotaped and distributed to DVD kiosks in Peshawar, northwestern Pakistan’s largest city, to hammer home the message.

Obama administration considers censoring Twitter

How dangerous can 140 characters be?

Apparently if those 140 characters are being fired onto the web through the Twitter account of al Shabib, Somalia’s militant jihadist movement, then the national security of the United States could be in jeopardy.

The New York Times reports:

American officials say they may have the legal authority to demand that Twitter close the Shabab’s account, @HSMPress, which had more than 4,600 followers as of Monday night.

The most immediate effect of the Obama administration’s threat appears to have been that @HSMPress (which has so far only made 114 tweets) has subsequently gained hundreds of new followers.

Is Twitter itself about to take a stand in defense of freedom of speech?

A company spokesman, Matt Graves, said [to a Times reporter] on Monday, “I appreciate your offer for Twitter to provide perspective for the story, but we are declining comment on this one.”

Last Wednesday, the New York Times reported from Nairobi in Kenya:

Somalia’s powerful Islamist insurgents, the Shabab, best known for chopping off hands and starving their own people, just opened a Twitter account, and in the past week they have been writing up a storm, bragging about recent attacks and taunting their enemies.

“Your inexperienced boys flee from confrontation & flinch in the face of death,” the Shabab wrote in a post to the Kenyan Army.

It is an odd, almost downright hypocritical move from brutal militants in one of world’s most broken-down countries, where millions of people do not have enough food to eat, let alone a laptop. The Shabab have vehemently rejected Western practices — banning Western music, movies, haircuts and bras, and even blocking Western aid for famine victims, all in the name of their brand of puritanical Islam — only to embrace Twitter, one of the icons of a modern, networked society.

On top of that, the Shabab clearly have their hands full right now, facing thousands of African Union peacekeepers, the Kenyan military, the Ethiopian military and the occasional American drone strike all at the same time.

But terrorism experts say that Twitter terrorism is part of an emerging trend and that several other Qaeda franchises — a few years ago the Shabab pledged allegiance to Al Qaeda — are increasingly using social media like Facebook, MySpace, YouTube and Twitter. The Qaeda branch in Yemen has proved especially adept at disseminating teachings and commentary through several different social media networks.

“Social media has helped terrorist groups recruit individuals, fund-raise and distribute propaganda more efficiently than they have in the past,” said Seth G. Jones, a political scientist at the RAND Corporation.

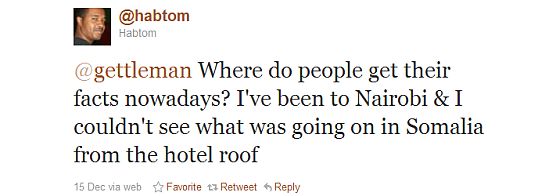

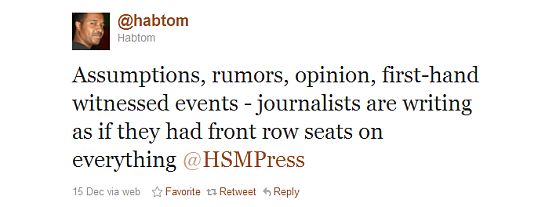

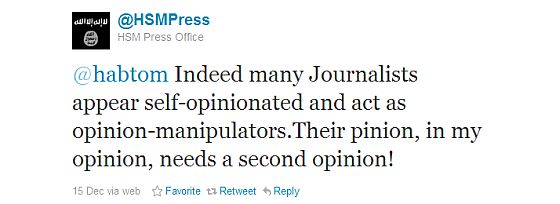

The Times reporter, Jeffrey Gettleman, sounds quite indignant that al Shabib should have the audacity to be using Twitter, so he can hardly have been surprised that his article prompted this exchange between @HSMPress and one of their followers:

Somalia is not the only front in the new war on Twitter.

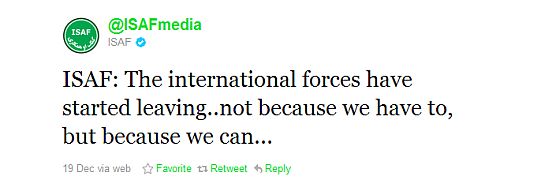

The Washington Post reports on Twitter battles in Afghanistan:

U.S. military officials assigned to the International Security Assistance Force, or ISAF, as the coalition is known, took the first shot in what has become a near-daily battle waged with broadsides that must be kept to 140 characters.

“How much longer will terrorists put innocent Afghans in harm’s way,” @isafmedia demanded of the Taliban spokesman on the second day of the embassy attack, in which militants lobbed rockets and sprayed gunfire from a building under construction.

“I dnt knw. U hve bn pttng thm n ‘harm’s way’ fr da pst 10 yrs. Razd whole vilgs n mrkts. n stil hv da nrve to tlk bout ‘harm’s way,’ ” responded Abdulqahar Balkhi, one of the Taliban’s Twitter warriors, who uses the handle @ABalkhi….

U.S. military officials say the dramatic assault on the diplomatic compound convinced them that they needed to seize the propaganda initiative — and that in Twitter, they had a tool at hand that could shape the narrative much more quickly than news releases or responses to individual queries.

“That was the day ISAF turned the page from being passive,” said Navy Lt. Cmdr. Brian Badura, a military spokesman, explaining how @isafmedia evolved after the attack. “It used to be a tool to regurgitate the company line. We’ve turned it into what it can be.”

So how’s @isafmedia exploiting the power of Twitter? With tweets like this?

A we’re-winning-the-war tweet like this might sound good inside ISAF’s Twitter Command Center, but I don’t think it’s going to impress anyone else.

The problem the Obama administration is up against is not the threat posed by its adversaries on Twitter; it is that its own ventures into social media are predictably inept. Official tweets lack wit and tend to sound like the clumsy propaganda. But when losing an argument, the solution is not to look for ways to gag your opponent — that’s how dictators operate.

The Pentagon prides itself on its smart bombs. Can’t it come up with a few smart tweets?

Secret U.S., Taliban talks reach turning point

Reuters reports: After 10 months of secret dialogue with Afghanistan’s Taliban insurgents, senior U.S. officials say the talks have reached a critical juncture and they will soon know whether a breakthrough is possible, leading to peace talks whose ultimate goal is to end the Afghan war.

As part of the accelerating, high-stakes diplomacy, Reuters has learned, the United States is considering the transfer of an unspecified number of Taliban prisoners from the Guantanamo Bay military prison into Afghan government custody.

It has asked representatives of the Taliban to match that confidence-building measure with some of their own. Those could include a denunciation of international terrorism and a public willingness to enter formal political talks with the government headed by Afghan President Hamid Karzai.

The officials acknowledged that the Afghanistan diplomacy, which has reached a delicate stage in recent weeks, remains a long shot. Among the complications: U.S. troops are drawing down and will be mostly gone by the end of 2014, potentially reducing the incentive for the Taliban to negotiate.

Still, the senior officials, all of whom insisted on anonymity to share new details of the mostly secret effort, suggested it has been a much larger piece of President Barack Obama’s Afghanistan policy than is publicly known.

U.S. officials have held about half a dozen meetings with their insurgent contacts, mostly in Germany and Doha with representatives of Mullah Omar, leader of the Taliban’s Quetta Shura, the officials said.

The stakes in the diplomatic effort could not be higher. Failure would likely condemn Afghanistan to continued conflict, perhaps even civil war, after NATO troops finish turning security over to Karzai’s weak government by the end of 2014.

Success would mean a political end to the war and the possibility that parts of the Taliban – some hardliners seem likely to reject the talks – could be reconciled.

The effort is now at a pivot point.

“We imagine that we’re on the edge of passing into the next phase. Which is actually deciding that we’ve got a viable channel and being in a position to deliver” on mutual confidence-building measures, said a senior U.S. official.

While some U.S.-Taliban contacts have been previously reported, the extent of the underlying diplomacy and the possible prisoner transfer have not been made public until now.

Why Afghans have come to hate Americans

U.S. and Afghan government officials are struggling to reach a strategic long-term agreement — the sticking point is Afghan opposition to night raids which have surged under the Obama administration and now happen as often as 40 times a night.

NATO officials say they have modified how night raids are conducted in response to the Afghan government’s concerns.

“Ninety-five percent of all night operations at this stage are already partnered,” said Brig. Gen. Carsten Jacobson, the NATO spokesman in Afghanistan. “So basically the recommendation of the traditional loya jirga is already put into action.”

“It is in our combined interest that as soon as possible, Afghanization is accomplished,” he added, referring to an Afghan takeover of security responsibility.

Mr. Faizi was unimpressed by that argument. “According to reports from our officials in different provinces, the Afghan security forces are leaving with the American forces to go conduct night operations without being informed directly where they are going, which house they are searching and who is the target,” he said.

While General Jacobson said night raids averaged 10 a night now, a recent study of night raids by the Open Society Foundations, financed by George Soros, estimated that 19 a night were taking place during the first three months of 2011.

The American military is so enamored of the tactic that some generals have said that without night raids, the United States may as well go home.

General Jacobson said that 85 percent of night raids took place without a single shot fired, and that over all such operations accounted for less than one percent of all civilian casualties.

Statistics might calm the doubts of feeble-minded U.S. senators, but they will have little to no impact on the perceptions of Afghans whose homes are being violated. To live in a country where there is an ever-present risk of foreign soldiers breaking into your house in the middle of the night is to live in a state of oppression. This is the nature of occupation.

[Aimal Faizi, the spokesman for President Hamid Karzai,] said the raids were the biggest complaints that Mr. Karzai heard when visitors from the provinces met with him.

“If one of the messages of the United States is to win the hearts and minds of the Afghan people, then these night raids are totally against this,” he said. “People are becoming more and more against the international presence in Afghanistan.”

On the frontlines of southern Helmand Province, the governor of Sangin district, Mohammad Sharif, is a critic of the practice, even though his district has been the center of some of the toughest fighting of the war, with among the highest casualty rates for NATO forces. He said the Special Operations forces that carried out the raids often got the wrong people, including many pro-government people. “People are not happy, and they feel bad toward Americans,” he said.

A high-ranking official in Helmand Province saw the matter differently, although he did not want to be quoted by name endorsing night raids because of their unpopularity. “So many Taliban commanders have been killed or detained in night raids, and if it wasn’t for them, we would not have the peace we now have,” he said. “Taliban commanders are like snakes: it’s hard to catch them, and night raids are their charmers.”

He also noted that trying to arrest a Taliban commander during the day would inevitably mean a battle, which might well cause casualties among bystanders.

Mr. Faizi said the president was concerned that in many cases, Afghan families were forced to give food and shelter to insurgents, and then later were blamed for doing so and arrested. “We think that all these night raids, they bring the conflict directly to the homes of the Afghan people,” he said. “It has to be the opposite, the fight has to be fought somewhere else.”