When the dead have all been counted, what will Israel have accomplished?

When the neocons start issuing desperate appeals to Israel – don’t stop fighting now – it becomes obvious the war is close to its predictably inconclusive end.

Even the Bush administration, loyal deliverer of Security Council vetoes could not turn back a wave of international pressure last night in New York. By abstaining from the ceasefire resolution last night essentially told Israel, we’re here for you, but we can’t give you any more cover.

Even Israel’s well-oiled media campaign is losing its wheels.

After more than 40 civilians died in a UN school in the Jabalya refugee camp, Israel has now retracted its claim that it was responding to fire from Hamas. “The IDF admitted in that briefing that the attack on the UN site was unintentional,” UNRWA spokesman Chris Gunness told Haaretz.

The UN now refuses to collude in the charade of humanitarian aid designed to be an adjunct for extending the military campaign. Three-hour relief windows don’t really work when the IDF starts killing relief workers who have been assured “safe passage.” Listen to NPR’s report on Israel’s apparent inability (or unwillingness) to honor its word.

Pointing to the likelihood that by the end of this war, Israel will have accomplished nothing — at a tremendous price — an editorial in Haaretz said:

Substantive gaps are emerging between Livni, on the one hand, and Barak and Olmert on the other. The latter two want to reach, with the help of Egypt and the United States, an agreement that will secure calm for some time in the south and prevent Hamas from getting stronger in the Gaza Strip. In other words, they will make do with a calm similar to the one that existed on the eve of Operation Cast Lead. Livni insists that a deal should not be allowed to be interpreted as recognition of Hamas. She is concerned that returning to the framework of the lull, which allowed Hamas to arm itself, could restore the group’s military advantage, and she would support a unilateral withdrawal from the Strip, without an agreement, with the understanding that any attempt to attack Israel will be met with severity.

The two positions are reasonable and backed by good arguments, but the conclusion of both is the same: The fighting needs to stop now and the IDF should exit Gaza immediately. After all, while they are debating, the pressure from within and from without is growing. The head of Military Intelligence said yesterday that the IDF is fighting in Gaza in areas that “are crowded and full of traps, between schools and mosques.”

By this he bolstered the assumption, which appears to be self evident, that the more the forces advance, the more complicated the situation will become, fraught with dangers, for both the military and civilians.

In the International Herald Tribune, Gideon Lichfield wrote:

Israel needs instead to abandon its military concept of deterrence in favor of a more pragmatic political one. What could deter Hamas is the fear that by using violence it will lose support among its people.

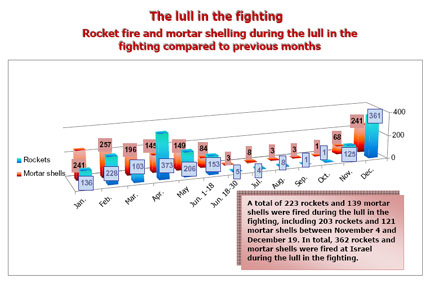

How to create this? It is worth remembering that Israel launched its operation after the breakdown of a cease-fire that had held, reasonably well, for several months. Each side accused the other of breaching it, both with some justification. Instead of trying to re-establish the cease-fire, Israel’s leaders, driven by the need to bolster their ratings ahead of an election in February, decided to try to strike a decisive blow against Hamas.

What Israel should do now is work for a cease-fire on terms that allow both sides to save some face. It should then do something it has done far too little of in the past: improve Gazans’ living conditions significantly. The aim should be to construct a long-lived state of calm in which Hamas has more to lose by breaching the cease-fire than by sticking to it.

In the longer term Israel will have to accept that Hamas is no fringe movement that can be rooted out and destroyed, but a central part of Palestinian society. This will be the hard part, not least because of the opposition from Hamas’ secularist Palestinian rivals, Fatah.

But even though Hamas’s stated goal is Israel’s destruction, it has said many times that it would accept a truce extending decades. Some former Israeli security chiefs argue that such an accommodation – a peace treaty in all but name – would eventually oblige Hamas to accept Israel’s existence, or else lose its own base of support. It is a gamble, certainly. But the alternative is more innocent lives lost, more extremism and ultimately more trouble for Israel.

e had no choice,” has become Israel’s national mantra.

e had no choice,” has become Israel’s national mantra.