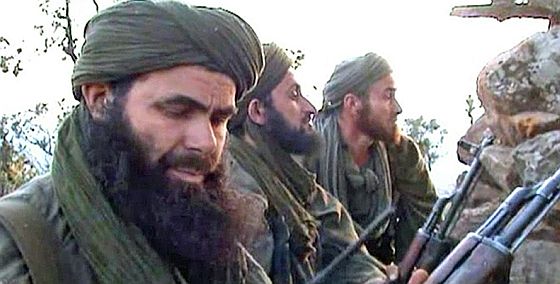

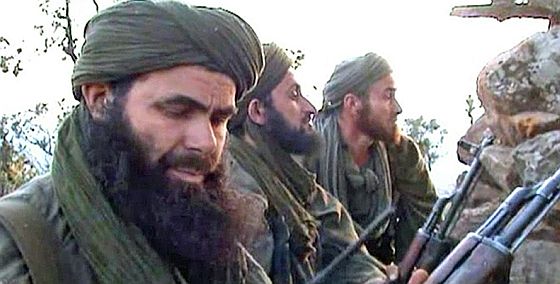

Abdelhamid Abou Zeid, an Algerian national and senior commander of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM).

In an analysis appearing in the New Internationalist last month, Jeremy Keenan, professor of social anthropology at London University’s School of Oriental and African Studies, explained how the current conflict in Mali is rooted in “a largely covert and highly duplicitous alliance” forged between Algerian President Abdelaziz Bouteflika and President George W Bush in the summer of 2001.

[T]he Bush administration and the regime in Algiers both needed a ‘little more terrorism’ in the region. The Algerians wanted more terrorism to legitimize their need for more high-tech and up-to-date weaponry. The Bush administration, meanwhile, saw the development of such terrorism as providing the justification for launching a new Saharan front in the Global War On Terror. Such a ‘second front’ would legitimize America’s increased militarization of Africa so as better to secure the continent’s natural resources, notably oil. This, in turn, was soon to lead to the creation in 2008 of a new US combat command for Africa – AFRICOM.

The first US-Algerian ‘false flag’ terrorist operation in the Sahara-Sahel was undertaken in 2003 when a group led by an ‘infiltrated’ DRS [the Algerian intelligence service] agent, Amari Saifi (aka Abderrazak Lamari and ‘El Para’), took 32 European tourists hostage in the Algerian Sahara. The Bush administration immediately branded El Para as ‘Osama bin Laden’s man in the Sahara’.

In 2002, a … plan was presented to US Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld by his Defense Science Board. Excerpts from its ‘Summer Study on Special Operations and Joint Forces in Support of Countering Terrorism’ were revealed on 16 August 2002, with Pamela Hess, William Arkin and David Isenberg, amongst others, publishing further details and analysis of the plan. The plan recommended the creation of a ‘Proactive, Preemptive Operations Group’ (P20G as it became known), a covert organization that would carry out secret missions to ‘stimulate reactions’ among terrorist groups by provoking them into undertaking violent acts that would expose them to ‘counter-attack’ by US forces.

My new book on the Global War On Terror in the Sahara (The Dying Sahara, Pluto 2013) will present strong evidence that the El Para operation was the first ‘test run’ of Rumsfeld’s decision, made in 2002, to operationalize the P20G plan. In his recent investigation of false flag operations, Nafeez Ahmed states that the US investigative journalist Seymour Hersh was told by a Pentagon advisor that the Algerian [El Para] operation was a pilot for the new Pentagon covert P20G programme.

[…]

Since the El Para operation, Algeria’s DRS, with the complicity of the US and the knowledge of other Western intelligence agencies, has used Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, through the almost complete infiltration of its leadership, to create a terrorist scenario. Much of the terrorist landscape that Algeria and its Western allies have painted in the Sahara-Sahel region is completely false.

The Dying Sahara analyzes every supposed ‘terrorism’ incident in the region over this last, terrible decade. It shows that a few are genuine, but that the vast majority were fabricated or orchestrated by the DRS. Some incidents, such as the widely reported Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb attack on Algeria’s Djanet airport in 2007, simply didn’t happen…

In order to justify or increase what I have called their ‘terrorism rents’ from Washington, the governments of Mali, Niger and Algeria have been responsible on at least five occasions since 2004 for provoking Tuareg into taking up arms, as in 2004 (Niger), 2005 (Tamanrasset, Algeria), 2006 (Mali), 2007-09 (Niger and Mali)…

Around the time of the El Para operation, the Pentagon produced a series of maps of Africa, depicting most of the Sahara-Sahel region as a ‘Terror Zone’ or ‘Terror Corridor’. That has now become a self-fulfilled prophecy. In addition, the region has also become one of the world’s main drug conduits. In the last few years, cocaine trafficking from South America through Azawad to Europe, under the protection of the region’s political and military élites, notably Mali’s former president and security forces and Algeria’s DRS, has burgeoned. The UN Office of Drugs Control recently estimated that 60 per cent of Europe’s cocaine passed through the region. It put its value, at Paris street prices, at some $11 billion, with an estimated $2 billion remaining in the region.

While it will be clear from all this that Mali’s latest Tuareg rebellion had a complex background, the rebellion that began in January 2012 was different from all previous Tuareg rebellions in that there was a very real likelihood that it would succeed, at least in taking control of the whole of northern Mali. The creation of the rebel MNLA in October 2011 was therefore not only a potentially serious threat to Algeria, but one which appears to have taken the Algerian regime by surprise. Algeria has always been a little fearful of the Tuareg, both domestically and in the neighbouring Sahel countries. The distinct possibility of a militarily successful Tuareg nationalist movement in northern Mali, which Algeria has always regarded as its own backyard, could not be countenanced.

The Algerian intelligence agency’s strategy to remove this threat was to use its control of Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb to weaken and then destroy the credibility and political effectiveness of the MNLA. This is precisely what we have seen happening in northern Mali over the last nine months.

In an interview last week, Scott Horton asked Keenan to further substantiate his claim that Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb has been supported by the Algerian government.

In this segment of the interview, Keenan describes a large camp deep in the Algerian Sahara in which AQIM fighters were trained while the camp was being supplied by the Algerian army and intelligence service.

The existence of this camp has been known by Western intelligence services for two or three years since at least two of these men were arrested in Europe. Keenan has been able to interview these AQIM members and then cross-check the information they provided with information he has gathered from independent sources.

Since 2008, much of that camp has been moved down into northern Mali, forming the base of the Islamist forces that have now taken over the area.