Category Archives: New York Times

NYT reporters parrot unsubstantiated statements from U.S. counterterrorism officials. What’s new?

A report in the New York Times claims in its opening paragraph:

The younger of the two brothers who killed 12 people in Paris last week most likely used his older brother’s passport in 2011 to travel to Yemen, where he received training and $20,000 from Al Qaeda’s affiliate there, presumably to finance attacks when he returned home to France.

The source of that information is presumably the American counterterrorism officials referred to in the second paragraph.

Reporters Eric Schmitt and Mark Mazzetti, too busy scribbling their notes, apparently didn’t bother asking these officials how they identified the money trail.

That’s an important question, because an alternative money trail has already been reported that has no apparent connection to AQAP.

French media have reported that Amedy Coulibaly — who in a video declared his affiliation with ISIS — purchased the weapons, used both by him and the Kouachi brothers, from an arms dealer in Brussels and that he paid for these with:

a standard loan of 6,000 euros ($7,050) that Coulibaly took out on December 4 from the French financial-services firm Cofidis. He used his real name but falsely stated his monthly income on the loan declaration, a statement the company didn’t bother to check, the reports say.

Whereas the New York Times reports receipt of the money and its amount as fact, CNN — no doubt briefed by the same officials — makes it somewhat clearer that this information is quite speculative:

U.S. officials have told CNN it’s believed that when Cherif Kouachi traveled to Yemen in 2011, he returned carrying money from AQAP earmarked to carry out the attack. Investigators said the terrorist group could have given as much as $20,000, but the exact amount has not been verified. [Emphasis mine.]

This isn’t a money trail — it’s speculation. And even if AQAP did put up some seed capital, that was four years ago. In the intervening period, the gunmen seem to have been busy engaged in their own entrepreneurial efforts:

Former drug-dealing associates of Coulibaly told AP he was selling marijuana and hashish in the Paris suburbs as recently as a month ago. Multiple French news accounts have said the Kouachi brothers sold knockoff sporting goods made in China.

Another gaping hole in the NYT report is its failure to analyze the AQAP videos — there were two.

The first video, released on January 9, praised the attacks but made no claim of responsibility. Were its makers restrained by their own modesty? The second video, which does claim that AQAP funded and directed the operation, provides no evidence to support these claims.

The top spokesman for the Yemen branch of al-Qaida publicly took credit Wednesday for the bloody attack on a French satirical newspaper, confirming a statement that had been emailed to reporters last week.

But the 11-minute video provided no hard evidence for its claims, including that the operation had been arranged by the American cleric Anwar al-Awlaki directly with the two brothers who carried it out before Awlaki was killed by a U.S. drone strike in 2011.

The video includes frames showing Awlaki but none of him with the brothers, Saïd and Chérif Kouachi, nor any images of the Kouachis that haven’t been shown on Western news broadcasts for days.

So it seems premature for the New York Times to start talking about how the attacks might:

serve as a reminder of the continued danger from the group [AQAP] at a time when much of the attention of Europe and the United States has shifted to the Islamic State, the militant organization that controls large swaths of Syria and Iraq and has become notorious for beheading hostages.

The NYT report also makes a claim that I have not seen elsewhere:

In repeated statements before they were killed by the police, the Kouachi brothers said they had carried out the attack on behalf of the Qaeda branch in Yemen, saying it was in part to avenge the death of Mr. Awlaki.

Are we to suppose that Awlaki was funding an operation to avenge his own death before he had been killed?

Based on the information that has been reported so far — and obviously, new information might significantly change this picture — the evidence seems to lean fairly strongly in the direction that the Paris attacks should be seen to have been inspired rather than directed by Al Qaeda.

And to the extent that Anwar al-Awlaki played a pivotal role in these attacks, the lesson — a lesson that should be reflected on by President Obama and the commanders of future drone strikes — is that Awlaki’s capacity to inspire terrorist attacks seems to be just as strong now as it was when he was alive.

Indeed, the mixed messages coming from AQAP might reflect an internal debate on whether it can wield more power as an inspirational force or alternatively needs to sustain the perception that it retains control over operations carried out in its name.

NYT reporter prevails in three-year fight over CIA leak

Bloomberg: New York Times reporter James Risen prevailed over the U.S. government in its three-year effort to force him to testify at trial about a confidential source as part of a CIA leak prosecution.

The request by prosecutors that Risen be dropped as a witness capped a longer battle to avoid revealing his sources. The fight reached the U.S. Supreme Court, focusing attention on the Obama administration’s aggressive pursuit of leaks. U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder reacted to the controversy by issuing guidelines last year restricting the use of subpoenas and search warrants for journalists.

Risen told a judge Jan. 5 he wouldn’t answer questions that could help identify the sources for his report on a bungled Central Intelligence Agency program to give Iran false nuclear weapon development data.

How the New York Times briefly invented a new country

This, from yesterday's New York Times, might be my favorite correction ever. HT @NYMag. pic.twitter.com/3f0zUzzKRo

— Kathryn Schulz (@kathrynschulz) January 8, 2015

A ‘quiet night’ in Gaza? Just five deaths and 25 sites bombed

Just imagine if in the space of 12 hours there were 25 bomb attacks in Israel and five people were killed.

In the United States, the cable news networks would devote round-the-clock coverage to the “terrorist bloodbath” (or whatever other sufficiently dramatic branding they chose) and this would go down as an important date in history.

But when the dead are Palestinians, it’s a completely different story.

The New York Times reports that last night was:

… a relatively quiet night, in which the Israeli military bombed 25 sites in Gaza, killing five Palestinians in the southern cities of Rafah and Khan Younis, according to the Gaza Health Ministry; about 1,400 others have been wounded.

Ashraf al-Qedra, the Health Ministry spokesman, and local journalists said that Ismail and Mohammed Najjar, relatives in their 40s who worked as guards on agricultural land in a former Israeli settlement in Khan Younis, were killed early Tuesday. In Rafah, drone strikes killed Atwa al-Amour, a 63-year-old farmer, and Bushra Zourob, 53, a woman who was near the target, a man on a motorbike, who was wounded.

Perhaps reporters Jodi Rudoren and Anne Barnard are employing Benjamin Netanyahu’s novel definition of quietness, that being: the silence that follows explosions.

The Israeli prime minister said:

[I]f Hamas does not accept the cease-fire proposal, as it looks now, Israel will have all the international legitimacy in order to achieve the desired quiet.

So far Israel has launched 1,609 air strikes, detonating hundreds of tons of explosives in order to create quietness.

Supreme Court rejects appeal from Times reporter over refusal to identify source

The New York Times reports: The Supreme Court on Monday turned down an appeal from James Risen, a reporter for The New York Times facing jail for refusing to identify a confidential source.

The court’s one-line order gave no reasons but effectively sided with the government in a confrontation between what prosecutors said was an imperative to secure evidence in a national security prosecution and what journalists said was an intolerable infringement of press freedom.

The case arose from a subpoena to Mr. Risen seeking information about his source for a chapter of his 2006 book, “State of War.” Prosecutors say they need Mr. Risen’s testimony to prove that the source was Jeffrey Sterling, a former C.I.A. official.

The United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, in Richmond, Va., ordered Mr. Risen to comply with the subpoena. Mr. Risen has said he will refuse. [Continue reading…]

In the Middle East, time for the U.S. to move on

The Editorial board of the New York Times writes: The pointless arguing over who brought Israeli-Palestinian peace talks to the brink of collapse is in full swing. The United States is still working to salvage the negotiations, but there is scant sign of serious purpose. It is time for the administration to lay down the principles it believes must undergird a two-state solution, should Israelis and Palestinians ever decide to make peace. Then President Obama and Secretary of State John Kerry should move on and devote their attention to other major international challenges like Ukraine.

Among those principles should be: a Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza with borders based on the 1967 lines; mutually agreed upon land swaps that allow Israel to retain some settlements while compensating the Palestinians with land that is comparable in quantity and quality; and agreement that Jerusalem will be the capital of the two states.

Perhaps the Obama administration’s effort to broker a deal was doomed from the start. In 2009, the administration focused on getting Israel to halt settlement building and ran into the obstinacy of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and resistance from the Palestinian president, Mahmoud Abbas, to entering peace talks. Since then, members of Mr. Netanyahu’s coalition government have tried to sabotage the talks. As Tzipi Livni, Israel’s chief negotiator, told the website Ynet, “There are people in the government who don’t want peace.” She cited Naftali Bennett, the leader of the pro-settler party Jewish Home, and Uri Ariel, the housing minister.

Mr. Obama made the right decision to give it a second try last summer, with Mr. Kerry bringing energy and determination to the negotiations. But, after nine months, it is apparent that the two sides are still unwilling to move on the core issues of the borders of a Palestinian state, the future of Jerusalem, the fate of Palestinian refugees and guarantees for Israel’s security. The process broke down last month when Israel failed to release a group of Palestinian prisoners as promised and then announced 700 new housing units for Jewish settlement in a part of Jerusalem that Palestinians claim as the capital of a future state. According to Mr. Kerry that was the “poof” moment when it all fell apart, and the Palestinians responded by applying to join 15 international conventions and treaties. That move won’t get them a state, but it is legal and they did not seek to join the International Criminal Court, a big fear of Israel’s.

In recent days, Israel, which denounced the Palestinians for taking unilateral steps, took its own unilateral steps by announcing plans to deprive the financially strapped Palestinian Authority of about $100 million in monthly tax revenues and retroactively legalizing a 250-acre outpost in the Gush Etzion settlement, which the Israeli newspaper Haaretz said was the largest appropriation of West Bank land in years.

An Israeli-Palestinian peace deal is morally just and essential for the security of both peoples. To achieve one will require determined and courageous leaders and populations on both sides that demand an end to the occupation. Despite the commitment of the United States, there’s very little hope of that now.

New York Times reporters collude in Israeli duplicity

Yesterday Jodi Rudoren, Isabel Kershner, and Michael R. Gordon reported that following Israel’s failure to release a fourth batch of long-serving Palestinian prisoners by March 29, and following the announcement of plans to build more than 700 new housing units in Israeli-occupied East Jerusalem, the Palestinian leadership submitted applications to join 15 international conventions and treaties, ignoring Israeli and American objections to such a move.

To put that more bluntly, the Israelis reneged on an agreement to release a group of prisoners, pressed ahead with new plans to expand the Judaification of East Jerusalem, and in response the Palestinians said, enough is enough, we’re going to see if we can make some progress at the UN instead of remaining mired in fruitless negotiations with the Israelis.

Today, as though they imagine no one could possibly remember what they wrote yesterday, Michael R. Gordon, Isabel Kershner and Jodi Rudoren, reported:

Israel has called off plans to release a fourth group of Palestinian prisoners, people involved in the threatened peace talks said Thursday, an indication of the severity of the impasse between the two sides despite the pressure from Secretary of State John Kerry to keep the negotiations alive.

The Israeli decision was a response to the announcement on Tuesday by the Palestinian president, Mahmoud Abbas, that his administration was formally seeking to join 15 international bodies, which the Israelis regarded as an unacceptable move that would subvert the direct negotiations with Israel for Palestinian statehood. Mr. Abbas said he took the step because Israel had not kept what he called its pledge to release the prisoners as part of the negotiations process, which began last summer.

What the Israelis did is like failing to show up for an appointment and then calling back the next day to cancel the appointment you already missed. What the New York Times did is try and make the Israelis seem perfectly reasonable.

What Pakistan knew about Bin Laden

In a long extract from her upcoming book, The Wrong Enemy: America in Afghanistan, 2001-2014, Carlotta Gall writes: Shortly after the Sept. 11 attacks, I went to live and report for The New York Times in Afghanistan. I would spend most of the next 12 years there, following the overthrow of the Taliban, feeling the excitement of the freedom and prosperity that was promised in its wake and then watching the gradual dissolution of that hope. A new Constitution and two rounds of elections did not improve the lives of ordinary Afghans; the Taliban regrouped and found increasing numbers of supporters for their guerrilla actions; by 2006, as they mounted an ambitious offensive to retake southern Afghanistan and unleashed more than a hundred suicide bombers, it was clear that a deadly and determined opponent was growing in strength, not losing it. As I toured the bomb sites and battlegrounds of the Taliban resurgence, Afghans kept telling me the same thing: The organizers of the insurgency were in Pakistan, specifically in the western district of Quetta. Police investigators were finding that many of the bombers, too, were coming from Pakistan.

In December 2006, I flew to Quetta, where I met with several Pakistani reporters and a photographer. Together we found families who were grappling with the realization that their sons had blown themselves up in Afghanistan. Some were not even sure whether to believe the news, relayed in anonymous phone calls or secondhand through someone in the community. All of them were scared to say how their sons died and who recruited them, fearing trouble from members of the ISI, Pakistan’s main intelligence service.

After our first day of reporting in Quetta, we noticed that an intelligence agent on a motorbike was following us, and everyone we interviewed was visited afterward by ISI agents. We visited a neighborhood called Pashtunabad, “town of the Pashtuns,” a close-knit community of narrow alleys inhabited largely by Afghan refugees who over the years spread up the hillside, building one-story houses from mud and straw. The people are working class: laborers, bus drivers and shopkeepers. The neighborhood is also home to several members of the Taliban, who live in larger houses behind high walls, often next to the mosques and madrasas they run. [Continue reading…]

This article appeared in most of the international editions of the New York Times with the exception of the Express Tribune in Pakistan. There, the paper’s printer removed the article.

New York Times op-ed ‘The Dustbowl Returns’ never mentions climate change

Joe Romm writes: In yet another example of how the New York Times is mis-covering the story of the century, it published an entire op-ed on the return of the Dust Bowl with no mention whatsoever of climate change.

It stands in sharp contrast to the coverage of the connection between climate change and extreme weather other leading news outlets and science journals. Consider the BBC’s Sunday article on the epic deluges hitting the UK, “Met Office: Evidence ‘suggests climate change link to storms’.” Consider the journal Nature, which back in 2011 asked me to write an article on the link between climate change and “Dust-bowlification”…

As James Hansen told me two weeks ago, “Increasingly intense droughts in California, all of the Southwest, and even into the Midwest have everything to do with human-made climate change.” [Continue reading…]

Truth in journalism

In a report exemplifying the kind of journalism-as-stenography in which David Sanger specializes, comes this observation about the pressures under which Director of National Intelligence James Clapper now operates — thanks to Edward Snowden:

The continuing revelations have posed a particular challenge to Mr. Clapper, a retired Air Force general and longtime intelligence expert, who has made no secret of his dislike for testifying in public. Critics have charged that he deliberately misled Congress and the public last year when asked if the intelligence agencies collected information on domestic communications. He was forced by the Snowden revelations to correct his statements, and he has been somewhat more careful in his testimony.

“Critics have charged” that Clapper perjured himself in Congress, but as studiously impartial journalists, Sanger (and his colleague Eric Schmitt) are incapable of making any determination on that matter.

This is really pseudo-impartiality since by avoiding using the word lied and framing this as a “charge” from “critics” the reporters are insinuating that Clapper might have merely made a mistake. Indeed, to say that he has since been more “careful” in his testimony suggests that his earlier statements were careless.

Seven members of Congress who in December called for a Justice Department investigation of Clapper, were not suffering from the same affliction which makes Times reporters mealy-mouthed so often. They called Clapper’s words by their real name: a willful lie.

Director Clapper has served his country with distinction, and we have no doubt he believed he was acting in its best interest. Nevertheless, the law is clear. He was asked a question and he was obligated to answer it truthfully. He could have declined to answer. He could have offered to answer in a classified setting. He could have corrected himself immediately following the hearing. He did none of these things despite advance warning that the question was coming.

The country’s interests are best served when its leaders deal truthfully with its citizens. The mutual sense of good faith it fosters permits compromise and concessions in those cases that warrant it. Director Clapper’s willful lie under oath fuels the unhealthy cynicism and distrust that citizens feel toward their government and undermines Congress’s ability to perform its Constitutional function.

There are differences of opinion about the propriety of the NSA’s data collection programs. There can be no disagreement, however, on the basic premise that congressional witnesses must answer truthfully.

A willingness to align oneself with those in positions of power is the explicit price of access for journalists who cherish their ability to communicate with senior officials, yet Jane Mayer describes how little such access can be worth:

Not long after coming to Washington in 1984 to cover the Reagan White House for The Wall Street Journal, I learned that Reagan’s embattled national security adviser was about to resign. I quickly went to see him and asked him about this point-blank, and with warm brown eyes that kind of looked like a trustworthy Labrador retriever, he looked across the desk at me and told me that he had absolutely no plans to resign.

I may be telescoping this in memory, but as I remember it, the very next day after I had shelved my story, they announced his resignation and I was stunned. Government officials lie. They lie to reporters boldly and straight-faced. It taught me that access is overrated. Never forget that the relationship between reporters and the subjects in power that we cover is, by necessity, one that is adversarial and sometimes full of distrust and opposition.

True. But I would argue that whether a journalist is aligned or in an adversarial relationship with power is an issue that can itself become a distraction.

What counts more than anything is a commitment to truth.

Such a commitment neither presupposes a trust or distrust of power. It is not in awe of power either positively or negatively. It recognizes that those perceived as the most important people in this world are never as grand as the positions they occupy.

New York Times: End the phone data sweeps

In an editorial, the New York Times says: Once again, a thorough and independent analysis of the government’s dragnet surveillance of Americans’ phone records has found the bulk data collection to be illegal and probably unconstitutional. Just as troubling, the program was found to be virtually useless at stopping terrorism, raising the obvious question: Why does President Obama insist on continuing a costly, legally dubious program when his own appointees repeatedly find that it doesn’t work?

In a 238-page report issued Thursday afternoon, the Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board, a five-member independent agency, called on the White House to end the phone-data collection program, for both constitutional and practical reasons. The board’s report follows a Dec. 16 ruling by Federal District Judge Richard Leon that the program was “almost certainly” unconstitutional and that the government had not identified “a single instance” in which it “actually stopped an imminent attack.”

Two days later, a panel of legal and intelligence experts convened by Mr. Obama after the disclosures by Edward Snowden echoed those conclusions in its own comprehensive report, which said the data sweep “was not essential to preventing attacks” and called for its end.

The growing agreement among those who have studied the program closely makes it imperative that the administration, along with the program’s defenders in Congress, explain why such intrusive mass surveillance is necessary at all. If Mr. Obama knows something that contradicts what he has now been told by two panels, a federal judge and multiple members of Congress, he should tell the American people now. Otherwise, he is in essence asking for their blind faith, which is precisely what he warned against during his speech last week on the future of government surveillance.

“Given the unique power of the state,” Mr. Obama said, “it is not enough for leaders to say: trust us, we won’t abuse the data we collect. For history has too many examples when that trust has been breached.”

The more likely reality is that the multiple analyses of recent weeks are correct, and that the phone-data sweeps have simply been ineffective. If they had assisted in the prevention of any terrorist attacks, it is safe to assume that we would know by now. Instead, despite repeated claims that the bulk-data collection programs had a hand in thwarting 54 terrorist plots, the privacy board members write, “we have not identified a single instance involving a threat to the United States in which the telephone records program made a concrete difference in the outcome of a counterterrorism investigation.”

That reiterates the findings of Judge Leon — who noted that even behind closed doors, the government provided “no proof” of the program’s efficacy — as well as the conclusion of a report released this month by the New America Foundation that the metadata program “had no discernible impact on preventing acts of terrorism and only the most marginal of impacts on preventing terrorist-related activity.”

No one disputes that the threat of terrorism is real and unrelenting, or that our intelligence techniques must adapt to a rapidly changing world. It is equally clear that the dragnet collection of Americans’ phone calls is not the answer.

New York Times calls on Obama to grant Snowden clemency

An Editorial in the New York Times says: Seven months ago, the world began to learn the vast scope of the National Security Agency’s reach into the lives of hundreds of millions of people in the United States and around the globe, as it collects information about their phone calls, their email messages, their friends and contacts, how they spend their days and where they spend their nights. The public learned in great detail how the agency has exceeded its mandate and abused its authority, prompting outrage at kitchen tables and at the desks of Congress, which may finally begin to limit these practices.

The revelations have already prompted two federal judges to accuse the N.S.A. of violating the Constitution (although a third, unfortunately, found the dragnet surveillance to be legal). A panel appointed by President Obama issued a powerful indictment of the agency’s invasions of privacy and called for a major overhaul of its operations.

All of this is entirely because of information provided to journalists by Edward Snowden, the former N.S.A. contractor who stole a trove of highly classified documents after he became disillusioned with the agency’s voraciousness. Mr. Snowden is now living in Russia, on the run from American charges of espionage and theft, and he faces the prospect of spending the rest of his life looking over his shoulder.

Considering the enormous value of the information he has revealed, and the abuses he has exposed, Mr. Snowden deserves better than a life of permanent exile, fear and flight. He may have committed a crime to do so, but he has done his country a great service. It is time for the United States to offer Mr. Snowden a plea bargain or some form of clemency that would allow him to return home, face at least substantially reduced punishment in light of his role as a whistle-blower, and have the hope of a life advocating for greater privacy and far stronger oversight of the runaway intelligence community.

•

Mr. Snowden is currently charged in a criminal complaint with two violations of the Espionage Act involving unauthorized communication of classified information, and a charge of theft of government property. Those three charges carry prison sentences of 10 years each, and when the case is presented to a grand jury for indictment, the government is virtually certain to add more charges, probably adding up to a life sentence that Mr. Snowden is understandably trying to avoid.

The president said in August that Mr. Snowden should come home to face those charges in court and suggested that if Mr. Snowden had wanted to avoid criminal charges he could have simply told his superiors about the abuses, acting, in other words, as a whistle-blower.

“If the concern was that somehow this was the only way to get this information out to the public, I signed an executive order well before Mr. Snowden leaked this information that provided whistle-blower protection to the intelligence community for the first time,” Mr. Obama said at a news conference. “So there were other avenues available for somebody whose conscience was stirred and thought that they needed to question government actions.”

In fact, that executive order did not apply to contractors, only to intelligence employees, rendering its protections useless to Mr. Snowden. More important, Mr. Snowden told The Washington Post earlier this month that he did report his misgivings to two superiors at the agency, showing them the volume of data collected by the N.S.A., and that they took no action. (The N.S.A. says there is no evidence of this.) That’s almost certainly because the agency and its leaders don’t consider these collection programs to be an abuse and would never have acted on Mr. Snowden’s concerns.

In retrospect, Mr. Snowden was clearly justified in believing that the only way to blow the whistle on this kind of intelligence-gathering was to expose it to the public and let the resulting furor do the work his superiors would not. Beyond the mass collection of phone and Internet data, consider just a few of the violations he revealed or the legal actions he provoked:

■ The N.S.A. broke federal privacy laws, or exceeded its authority, thousands of times per year, according to the agency’s own internal auditor.

■ The agency broke into the communications links of major data centers around the world, allowing it to spy on hundreds of millions of user accounts and infuriating the Internet companies that own the centers. Many of those companies are now scrambling to install systems that the N.S.A. cannot yet penetrate.

■ The N.S.A. systematically undermined the basic encryption systems of the Internet, making it impossible to know if sensitive banking or medical data is truly private, damaging businesses that depended on this trust.

■ His leaks revealed that James Clapper Jr., the director of national intelligence, lied to Congress when testifying in March that the N.S.A. was not collecting data on millions of Americans. (There has been no discussion of punishment for that lie.)

■ The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court rebuked the N.S.A. for repeatedly providing misleading information about its surveillance practices, according to a ruling made public because of the Snowden documents. One of the practices violated the Constitution, according to the chief judge of the court.

■ A federal district judge ruled earlier this month that the phone-records-collection program probably violates the Fourth Amendment of the Constitution. He called the program “almost Orwellian” and said there was no evidence that it stopped any imminent act of terror.

The shrill brigade of his critics say Mr. Snowden has done profound damage to intelligence operations of the United States, but none has presented the slightest proof that his disclosures really hurt the nation’s security. Many of the mass-collection programs Mr. Snowden exposed would work just as well if they were reduced in scope and brought under strict outside oversight, as the presidential panel recommended.

When someone reveals that government officials have routinely and deliberately broken the law, that person should not face life in prison at the hands of the same government. That’s why Rick Ledgett, who leads the N.S.A.’s task force on the Snowden leaks, recently told CBS News that he would consider amnesty if Mr. Snowden would stop any additional leaks. And it’s why President Obama should tell his aides to begin finding a way to end Mr. Snowden’s vilification and give him an incentive to return home.

NYT and Washington Post provide cover for Israel lobby’s efforts to obstruct Iran deal

Philip Weiss writes: The lobby is doing its utmost to sandbag the breakthrough agreement between the U.S. and Iran. The Congress is now readying yet more sanctions bills; the Forward says Democrats are backing the legislation or doing nothing to oppose it because “These are the men and the women, after all, who are on a first-name basis with most of the board of AIPAC.” MJ Rosenberg says the Israel lobby is the reason Sens. Tim Kaine, Sherrod Brown and — conspicuously — progressive Elizabeth Warren have been silent on the diplomatic breakthrough.

One reason that supposed liberals can get away with this is that the New York Times and the Washington Post give them no heat. In reporting on the sanctions effort, our leading papers leave out the lobby’s role, allowing the nightflower to remain a nightflower. [Continue reading…]

The New York Times v. Obama

In an editorial, the Washington Times says: The New York Times intends to take its case against the Obama administration to the Supreme Court. In July, the 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals sided with administration lawyers in ruling that New York Times reporter James Risen must reveal the confidential sources he used for a series of articles and a 2006 book, “State of War,” about the CIA’s bungled efforts to stop Iran’s nuclear program. On Tuesday, the 4th Circuit refused to change its mind, leaving the Supreme Court with the final say in the matter.

Mr. Risen’s investigative work has assumed new significance now that we’ve learned the breathtaking scope of the National Security Agency collection of telephone calls, emails and GPS location data. Mr. Risen won the 2006 Pulitzer Prize for exposing the existence of a domestic wiretapping program. This was a thin slice of the larger program, but it was a hotly guarded secret at the time. Attorney General Eric H. Holder Jr. personally authorized government agents to go after Mr. Risen in court, which gives his instructions every appearance of payback.

The federal government should never be allowed to engage in vendettas against the press, and this is not special pleading for newspapers. Exposing embarrassing foreign-policy failures and the existence of constitutionally questionable domestic surveillance enterprises is precisely the job of reporters in a free society. The Founding Fathers understood this, which is why the language of the First Amendment plainly says that Congress can’t do anything to abridge the freedom of the press. James Madison explained further that “the liberty of conscience and of the press cannot be canceled, abridged, restrained or modified by any authority of the United States.” Abridging press freedom is abridging the speech of everyone. [Continue reading…]

How does journalism turn into stenography?

Margaret Sullivan, public editor for the New York Times, writes: Eric Schmitt remembers being surprised when, as a member of a Times newsroom committee on reporting practices, he was given information about what bothered readers of The Times most. It wasn’t political bias, or factual errors, or delivery problems.

“The No. 1 complaint, far and away, was anonymous sources,” Mr. Schmitt, a longtime and well-respected national security reporter in the Washington bureau, told me last week. “It goes to the heart of our credibility.”

The committee’s 2004 report followed two damaging episodes at The Times: the flawed reporting in the run-up to the Iraq war and the dishonesty of the rogue reporter Jayson Blair. That report reminded journalists to use anonymous sources sparingly. The current stylebook puts it this way: “Anonymity is a last resort.”

Mr. Schmitt and I talked last week because I had criticized an article that he co-wrote earlier this month, which not only relied heavily on anonymous government sources but also described them in the most general terms, including “a U.S. official.”

From that conversation, and others with Times journalists, and from the contact I have continually with readers, I see a disconnect — a major gap in understanding — between how journalists perceive the use of anonymous sources and how many readers perceive them.

For many journalists, they can be a necessity. And that necessity is increasing — especially for stories involving national security — now that the Obama administration’s crackdown on press leaks has made news sources warier of speaking on the record. (Leonard Downie Jr., a former executive editor of The Washington Post, has written revealingly about this for the Committee to Project Journalists.)

“It’s almost impossible to get people who know anything to talk,” Bill Hamilton, who edits national security coverage for The Times, told me. Getting them to talk on the record is even harder. “So we’re caught in this dilemma.”

But for many readers, anonymous sources are a scourge, a detriment to the straightforward, believable journalism they demand. With a greater-than-ever desire for transparency in journalism, readers see this practice as “stenography” — the kind of unquestioning reporting that takes at face value what government officials say.

Whether journalism appears like stenography does not hinge on over-reliance on anonymous sources. It can just as easily come in the form of an on-the-record interview such as one with director of the NSA, Gen. Keith B. Alexander, published yesterday.

Reporters David E Sanger and Thom Shanker wrote: “He has given a number of speeches in recent weeks to counter a highly negative portrayal of the N.S.A.’s work, but the 90-minute interview was his most extensive personal statement on the issue to date.”

Given the paltry amount of information their report contains, one has to ask: what were they talking about for 90 minutes?

If journalists want to demonstrate that they are not operating like stenographers, then they need to start reporting on the process of reporting.

“The director of the National Security Agency, Gen. Keith B. Alexander, said in an interview that to prevent terrorist attacks he saw no effective alternative to the N.S.A.’s bulk collection of telephone and other electronic metadata from Americans.”

Did Sanger or Shanker challenge that assertion? Did they point out that by the NSA’s own admission there has only been one conviction that was based on the use of this data?

If during the course of a 90 minute interview, Alexander made few substantive statements, was it because he wasn’t being asked any tough questions or because he deflected or refused to answer such questions?

Transparency is not simply about sources revealing their identities; it’s also about journalists revealing how they work.

We get told: “General Alexander was by turns folksy and firm in the interview.” And how were the reporters? Chummy? Meek? Deferential?

In a July report on the NSA tightening its security procedures, Sanger’s primary source was Ashton B. Carter, the deputy secretary of defense. Sanger neglected to mention that Carter is “an old friend of many, many years”. Is Alexander another of Sanger’s old friends?

Margaret Sullivan: An NYT ombud who dares to challenge her paper’s cozy relationship with the government

Greg Mitchell writes: With criticism and debate over the Obama administration’s deadly drone policy at a high level, it’s easy to forget that this was not the case until very recently. What set off the uproar was NBC’s decision in early February to publish a Justice Department white paper on rules governing US drone strikes aimed at American citizens abroad. This led to an examination of the entire program by the media and some in Congress, and put John Brennan on the spot during his congressional confirmation hearings for director of the Central Intelligence Agency.

Although the White House has drawn criticism, less has been said about the media’s failure to probe the drone program, and the way they knuckled under to government requests to withhold secrets. One of the few prominent critics of this journalistic “cover-up” was Margaret Sullivan, who happened to be working at the nation’s most influential media outlet, The New York Times. Her main target was… The New York Times.

Sullivan, the former editor of Warren Buffett’s Buffalo News, became the latest person appointed to the paper’s rotating post of public editor (a variety of ombudsman) last September. On October 13, she took the Times to task, charging that “its reporting has not aggressively challenged the administration’s description of those killed as ‘militants’ — itself an undefined term. And it has been criticized for giving administration officials the cover of anonymity when they suggest that critics of drones are terrorist sympathizers…. With its vast talent and resources, The Times has a responsibility to lead the way in covering this topic as aggressively and as forcefully as possible, and to keep pushing for transparency so that Americans can understand just what their government is doing.”

This earned her the praise of others who have criticized previous public editors at the Times for their soft critiques of the paper. “On drones and the Times’s withdrawal from the ‘informal arrangement’ not to disclose the Saudi Arabia base, she was right,” Erik Wemple, a Washington Post media critic, told me. “Right and quick, too. I was pursuing interviews with the paper that morning, and she beat me to the punch, scoring a bunch of insightful material from [managing editor] Dean Baquet.”

When I recently asked Sullivan for an update on her current concerns, she replied, “This is a subject that is very important to me, and I’m sure I will keep paying close attention to it. I did see after I wrote about it in October that there was a slightly different and more precise use of the language in stories, and I was heartened by that. The key is not just the language but the whole question of secrecy around the program and how the newspaper interacts with the government.”

But the drone column and later posts on this subject were hardly exceptions to Sullivan’s crisp reviewing. Among other issues she has raised that drew wide coverage and might even have sparked changes: the policy of the Times, and many other outlets, of granting quote approval to their sources; the perils of “false equivalency” in covering hot-button issues; social media posts by Jodi Rudoren, the newspaper’s Jerusalem bureau chief, that appeared to reveal bias against Palestinians in Gaza; the paper’s failure to send a reporter to cover Pfc. Bradley Manning’s first day of testimony at his trial for passing documents to WikiLeaks; the paper’s decision in early March to shut down its popular “Green” blog on environmental issues; and many more. [Continue reading…]

The New York Times’s English problem

Philip B. Corbett, who is in charge of The New York Times’s style manual and has the dubious title of associate managing editor for standards, is responsible for policing sentences like the following, which appeared in a February 8 article:

It turned out the activity was centered around a high school in Orange County.

Centered around? Goodness me. Mr. Corbett knows when a journalist needs a citation and so pulls out his rulebook where it says:

Centered around? Goodness me. Mr. Corbett knows when a journalist needs a citation and so pulls out his rulebook where it says:

center(v.). Do not write center around because the verb means gather at a point. Logic calls for center on, center in or revolve around.

Stan Carey, a linguist who unlike Corbett does not have his head stuck in the wrong place, points out the center around is an idiom and language isn’t geometry or logic. Corbett probably missed that tweet, or “twitter message,” as the Times insists on calling such pithy statements.

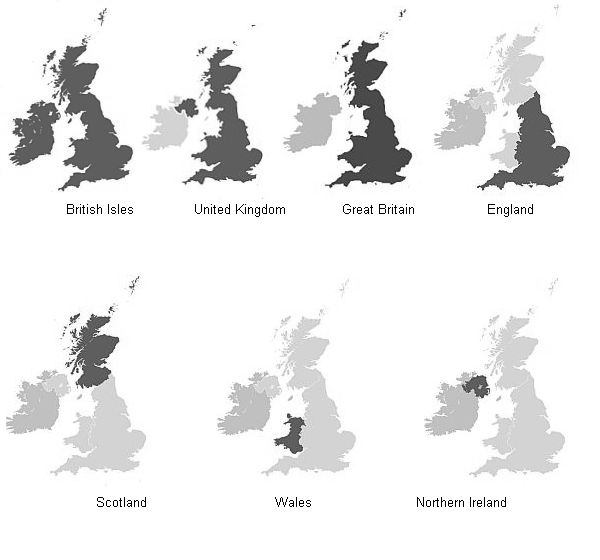

Meanwhile, I came across another lapse in the newspaper — one so commonplace among Americans that even the man in charge of “standards” at the Times probably sees no reason to correct it: the use of England and Britain as synonyms.

In “England Develops a Voracious Appetite for a New Diet,” Jennifer Conlin happily exchanges England and Britain, home of the British, in a way that those of us who hail from those parts and now live this side of the pond, know as all too familiar.

Explaining to an American that England and Britain are not the same, can end up feeling like providing an unsolicited tutorial in quantum physics. It’s an issue that probably lies far outside of the scope of the New York Times style guide.

But for what it’s worth — and that probably isn’t much — I put together a nifty graphic for those readers who have an interest and would not be at risk of mistaking the British Isles for a Rorschach blot.

And to round off the picture with a few small caveats: Britain, the UK, and United Kingdom are synonyms for the sovereign state that belongs to the European Union. Its citizens are British, though Catholics in Northern Ireland generally identify themselves as Irish. There are British who identify themselves as either English, Welsh, Scottish, Irish or none of the above. And some of the above don’t identify themselves as British.

Is that all clear? I can’t for the life of me understand why Americans find this confusing!

(Just in case anyone suspects that my omission of the labeling of the Republic of Ireland from this graphic represents some kind of British prejudice — far from it. I wouldn’t want to insult the Irish by including them in a parsing of the meaning of British.)