The New York Times reports: The death toll from renewed violence in Egypt’s capital rose overnight as clashes between Egyptian soldiers and protesters entered a second day on Saturday.

According to media reports, soldiers swept into Tahrir Square here on Saturday, chasing protesters and beating them with sticks.

Early Saturday, according to The Associated Press, hundreds of protesters hurled stones at security forces who sealed off the streets around Parliament with barbed wire and large concrete blocks. Soldiers on rooftops pelted the crowds below with stones, prompting many of the protesters to pick up helmets, satellite dishes or sheets of metal to try to shield themselves.

Reuters reported that protesters fled into side streets to escape the troops in riot gear, who grabbed people and battered them repeatedly even after they had been beaten to the ground.

Stones, dirt and shattered glass littered the streets downtown, while flames leapt out of the windows of a two-story building set ablaze near Parliament, sending thick plumes of black smoke into the sky, according to media reports. Soldiers set fire to tents inside the square, The A.P. reported, and swept through buildings where television crews were filming from and confiscated their equipment and briefly detained journalists.

In footage filmed by Reuters one soldier in a line of charging troops drew a pistol and fired a shot at retreating protesters.

The clashes began in the center of Cairo on Friday and at vote-counting centers around the country, preceding a decision by a new civilian advisory council to suspend its operations. That move, embarrassing to the country’s military rulers, was done in protest over the military’s deadly but ineffective treatment of peaceful demonstrators.

Category Archives: Arab Spring

Syria’s torture machine

Jonathan Miller reports: A short drive from the frontier, along hair-pinned mountain roads, past Lebanese checkpoints where friendly soldiers shiver, is a Syrian safe-house. There is no electricity. The place is crammed with refugees; there are children sleeping everywhere. In an upstairs room, next to a small wood-burner, a weathered former tractor driver from Tal Kalakh – who is in his 50s – winces as pains shoot through his battered body, lying on a mattress on the concrete floor. He manoeuvres himself on to a pile of pillows and lights a cigarette. He’s relieved to have escaped to Lebanon but he’s already yearning to go home. He can’t though. His right leg is now gangrenous below the knee; he can barely move. So far he’s had only basic medical treatment.

Before sunrise one morning, he told me, as troops laid siege to his town, he’d been shot twice by “shabiha”, pro-al-Assad militia. Unable to run, he had been rounded up, thrashed and driven down the road to nearby Homs with many other detainees, being beaten all the way. For the next few weeks, his bullet wounds were left to fester, he says, while he was subjected to torture so extreme that his accounts of what had happened to him left those of us who listened stunned and feeling sick. During his time in detention, he had been passed, he claimed, to five different branches of al-Assad’s sadistic secret police, the Mukhabarat.

In flickering candle-light, he told me in gruesome detail of beatings he’d received with batons and electric cables on the soles of his feet (a technique called “falaka”). He had been hung by his knees, immobilised inside a twisting rubber tyre, itself suspended from the ceiling. He had been shackled hand and foot and hung upside down for hours – the Mukhabarat’s notorious “flying carpet”. Then hung up by his wrists (“the ghost”), and whipped and tormented with electric cattle prods.

When he wasn’t being tortured, he had been crammed into cells with up to 80 people, without room to sit or sleep, he claimed. They stood hungry, naked and frightened in darkness, in their filth, unfed, unwashed. He recalled the stench and listening to the screams of others echoing through their sordid dungeon. He told of being thrown rotting food. And of the sobbing of the children.

“I saw at least 200 children – some as young as 10,” he said. “And there were old men in their 80s. I watched one having his teeth pulled out by pliers.” In Syria’s torture chambers, age is of no consequence, it seems. But for civilians who have risen up against al-Assad, it has been the torture – and death in custody – of children that has caused particular revulsion.

The tractor driver told of regular interrogations, of forced confessions (for crimes he never knew he had committed); he spoke of knives and other people’s severed fingers, of pliers and ropes and wires, of boiling water, cigarette burns and finger nails extracted – and worse: electric drills. There had been sexual abuse, he said, but that was all he said of that.

Having finished in one place, he’d been transferred to yet another branch of the Mukhabarat and his nightmare would start all over again. And as the beatings went on day in, day out, his legs and the soles of his feet became raw and infected. That was when they forced him to “walk on rocks of salt”. He told me, speaking clearly, slowly: “When you are bleeding and the salt comes into your flesh, it hurts a lot more than the beating. I was forced to walk round and round to feel more pain.”

He lit another cigarette, then said: “Although we are suffering from torture, we are not afraid any more. There is no fear. We used to fear the regime, but there is no place for fear now.” If the intention of torture is to terrorise, it has in recent months had the opposite effect. Each act of brutality has served, it seems, to reinforce the growing sense of outrage and injustice and has triggered ever more widespread insurrection.

A revolution for all seasons

Ordinary citizens at war — the ‘Martyr’s Brigade’ fighting outside Misrata in Libya

The success of Egypt’s Islamists marks a trend throughout the region

The Economist looks at the Muslim Brotherhood and the Salafists represented by the Nour party, whose combined successes in the first round of Egypt’s parliamentary elections give an overall majority to the Islamists.

Surrounded by well-wishers at his home on a narrow dirt street in the village of Nazla, Wagih al-Shimi insists his Nour party would have done even better if the Brothers had not cheated. Blind from birth and lushly bearded, Fayoum’s new MP is a doctor of Islamic jurisprudence, preaches in local mosques, and has a reputation for resolving disputes according to Islamic law.

“We owe our success to the people’s trust, to their love for us because we work for the common good, not personal gain,” says Mr Shimi. As for a party programme, he says his lot will improve schools, provide jobs and reform local government, introducing elections at every level to replace Mubarak-era centrally appointed officials. As for the wider world Mr Shimi is vague, except to say that Egypt should keep peace with any neighbour that refrains from attacking it.

The Brotherhood echoes this parochialism: its party’s 80-page manifesto mentions neither Israel nor Palestine. The two groups have more in common. The Brothers profess to share the Salafists’ end goal; namely, to regain the pre-eminent role for Islam in every aspect of life that they believe it once held. Some leading Brothers even describe themselves as Salafist in ideology. Many secular Egyptians, too, especially Coptic Christians, who make up an increasingly beleaguered 10% minority, see little difference between rival Islamists.

Yet within the broad spectrum of political Islam, the distinctions between two are telling. Muslim Brothers tend to be upwardly mobile professionals, whereas the Salafists derive their strength from the poor. The Brothers speak of pragmatic plans and wear suits and ties. The Salafists prefer traditional robes and clothe their language in scripture. The Brothers see themselves as part of a wide, diverse Islamist trend. The Salafists fiercely shun Shia Muslims. Asked what he thinks of Turkey’s mild Islamist rule, a Nour spokesman snaps that his party had nothing to take from Turkey bar its economic model.

Nour says it rejects Iranian-style theocracy, but equally rejects “naked” Western-style democracy. Instead, in what some Salafists see as a daring departure from previous condemnation of anything that might dilute God-given laws, it wants a “restricted” democracy confined by Islamic bounds. Yasir Burhami, a top Salafist preacher, says that his mission is to “uphold the call to Islam, not to impose it on people.” Still, he believes the party can convince Egyptians to accept such things as banning alcohol, adopting the veil and segregating the sexes in public because “we want them to go to heaven”.

Brotherhood leaders say instead that they must respect the people’s choice. Their party includes a few Christians. It worked hard to build a coalition with secularists, too, though most of its partners soon withdrew. Whereas Nour party leaders openly call for an alliance with the Brothers to pursue a determined Islamist agenda, the older group, with its long experience of persecution, is wary. It says fixing Egypt’s ailing economy should take priority over promoting Islamic mores. The Brotherhood would probably prefer a centrist alliance that would not frighten foreign powers or alienate Egypt’s army, which remains an arbiter of last resort.

In any case, a Brotherhood-led government is not in the immediate offing. Egypt’s generals, discomfited as anyone by the Islamists’ advance, seem determined to find ways to delay it.

The New York Times reports: In the aftermath of the vote, Egyptian liberals, Israelis and some Western officials have raised alarms that the revolution may unfold as a slow-motion version of the 1979 overthrow of the shah of Iran: a popular uprising that ushered in a conservative theocracy. With two rounds of voting to go, Egypt’s military rulers have already sought to use the specter of a Salafi takeover to justify extending their power over the drafting of a new constitution. And at least a few liberals say they might prefer military rule to a hard-line Islamist government. “I would take the side of the military council,” said Badri Farghali, a leftist who last week won a runoff against a Salafi in Port Said, northeast of Cairo.

A closer examination of the Salafi campaigns, however, suggests their appeal may have as much to do with anger at the Egyptian elite as with a specific religious agenda. The Salafis are a loose coalition of sheiks, not an organized party with a coherent platform, and Salafi candidates all campaign to apply Islamic law as the Prophet Muhammad did, but they also differ considerably over what that means. Some seek within a few years to carry out punishments like cutting off the hands of thieves, while others say that step should wait for the day when they have redistributed the nation’s wealth so that no Egyptian lacks food or housing.

But alone among the major parties here, the Salafi candidates have embraced the powerful strain of populism that helped rally the public against the crony capitalism of the Mubarak era and seems at times to echo — like the phrase “silent majority” — right-wing movements in the United States and Europe.

“We are talking about the politics of resentment, and it is something that right-wing parties do everywhere,” said Shadi Hamid, director of research at the Brookings Doha Center in Qatar. They have thrived, he said, off the gap between most Egyptians and the elite — including the leadership of the Muslim Brotherhood — both in lifestyle and outlook.

“They feel like they represent a significant part of Egypt,” Mr. Hamid said, “and that no one gives them any respect.”

UN says deaths in Syria unrest exceed 5,000

Al Jazeera reports: More than 5,000 people are now believed to have been killed in the Syrian government’s crackdown on protests, the United Nations rights chief has told the UN Security Council.

The UN’s Navi Pillay said on Monday there were reports of increased attacks by opposition groups on President Bashar al-Assad’s security forces but highlighted “alarming” events in the besieged protest city of Homs, according to diplomats in the closed meeting.

More than 14,000 people are estimated to have been detained and at least 300 children are among the dead, Pillay told the 15-nation council, according to diplomats.

She estimated that at least 12,400 have fled into neighbouring countries since the anti-government protests erupted in March.

Blogger, Rami al-Jarrah, describes his escape from Syria

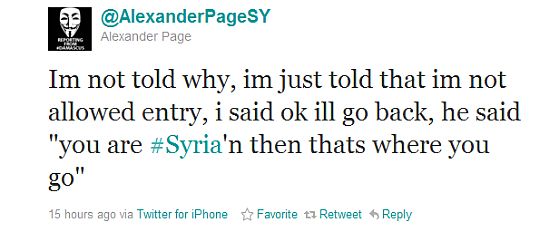

Rami al-Jarrah, who was blogging and tweeting from Syria under the pseudonym “Alexander Page,” just fled the country after his real identity became known to the intelligence services. Upon his arrival in Qatar he almost got sent back to Syria but thanks to a swift outpouring of support on Twitter, he was allowed in.

Syrians ‘strike for dignity’

Factional splits in Syrian opposition hinder drive to topple Assad

The New York Times: Even as the government of President Bashar al-Assad intensifies its crackdown inside Syria, differences over tactics and strategy are generating serious divisions between political and armed opposition factions that are weakening the fight against him, senior activists say.

Soldiers and activists close to the rebel Free Syrian Army, which is orchestrating attacks across the border from inside a refugee camp guarded by the Turkish military, said Thursday that tensions were rising with Syria’s main opposition group, the Syrian National Council, over its insistence that the rebel army limit itself to defensive action. They said the council moved this month to take control of the rebel group’s finances.

“We don’t like their strategy,” said Abdulsatar Maksur, a Syrian who said he was helping to coordinate the Free Syrian Army’s supply network. “They just talk and are interested in politics, while the Assad regime is slaughtering our people.” Repeating a refrain echoed by other army officials interviewed, he added: “We favor more aggressive military action.”

The tensions illustrate what has emerged as one of the key dynamics in the nine-month revolt against Mr. Assad’s government: the failure of Syria’s opposition to offer a concerted front. The exiled opposition is rife with divisions over personalities and principle. The Free Syrian Army, formed by deserters from the Syrian Army, has emerged as a new force, even as some dissidents question how coordinated it really is. The opposition inside Syria has yet to fully embrace the exiles.

Has Egypt’s revolution left women behind?

Mara Revkin writes: Millions of women were among the 52 percent of eligible voters who cast ballots in Egypt’s parliamentary elections this week, but preliminary results suggest that Egypt’s first popularly elected legislature since the revolution might not include a single female face. Despite anecdotal reports of massive female turnout in Cairo and the other eight governorates that cast ballots in this first of three rounds of voting, women may very well be the biggest losers of an election that has been hailed as the freest and fairest in Egypt’s recent history. Although 376 female candidates are running for parliament, not a single woman has won a seat so far in the 508-seat People’s Assembly after the first two days of voting on November 28 and 29 and this week’s runoff races. And there is good reason to believe that women will fare just as poorly in subsequent rounds of voting.The second and third stages of elections, slated for December and January, will include Egypt’s most rural and conservative districts where gender biases are more deeply ingrained than the urban centers of Cairo, Alexandria, and Port Said that voted this week. Faced with the possibility of an entirely male parliament, many Egyptians are wondering: Were women left behind by the Revolution?

Women have been on the frontlines of protests in Tahrir Square since the earliest days of the uprising and were instrumental in mobilizing the grassroots groundswell on Twitter and Facebook. But as activist youth movements like the Revolutionary Youth Coalition struggle to define their role in the post-revolutionary system — pondering if and how they should convert the momentum of the street into formal political representation — women are increasingly being left out of the conversation. While it’s true that the forty some-odd parties launched since last January have welcomed women as members and in some leadership positions, when it came time to nominate candidates for the parliamentary elections, women were conspicuously absent from the party lists. In late October, as parties began lining up their candidate rosters for the two thirds of parliamentary seats that will be allocated by closed-list proportional representation, Gameela Ismael, one of Egypt’s most prominent political activists and the ex-wife of presidential candidate Ayman Nour, publicly defected from the Democratic Alliance — a primarily Islamist coalition dominated by the Muslim Brotherhood’s Freedom and Justice Party — just weeks before the election, citing the coalition’s discriminatory stance against female candidates.

Egypt’s military tightens reins on government

Military still stands in the way of democracy in Egypt

The New York Times reports: Egypt’s military rulers said Wednesday that they would control the process of writing a constitution and maintain authority over the interim government to check the power of Islamists who have taken a commanding lead in parliamentary elections.

In an unusual briefing evidently aimed at Washington, Gen. Mukhtar al-Mulla of the ruling council asserted that the initial results of elections for the People’s Assembly do not represent the full Egyptian public, in part because well-organized factions of Islamists were dominating the voting. The comments, to foreign reporters and not the Egyptian public, may have been intended to persuade Washington to back off its call for civilian rule.

“So whatever the majority in the People’s Assembly, they are very welcome, because they won’t have the ability to impose anything that the people don’t want,” General Mulla said, explaining that the makeup of Parliament will not matter because it will not have power over the constitution.

He appeared to say that the vote results could not be representative because the Egyptian public could not possibly support the Islamists, especially the faction of ultraconservative Salafis who have taken a quarter of the early voting.

“Do you think that the Egyptians elected someone to threaten his interest and economy and security and relations with international community?” General Mulla asked. “Of course not.”

The military’s insistence on controlling the constitutional process was the latest twist in a struggle between the generals’ council and a chorus of liberal and Islamist critics who want the elected officials to preside over the writing of a new constitution.

‘Every Syrian has lost someone. Now we are ready to fight back’

The Independent reports: The sharp pop of gunfire draws little reaction. The soldiers of the Free Syrian Army (FSA) point to a multi-storey house just across the wide valley from their base above the village of Ain al-Baida, about a mile from the Turkish border. “That is where the military is,” says commander Abo Mohammad, who wears a camouflage jacket over civilian clothes and cradles an AK-47.

Unlike many of the 150 fighters he claims are positioned in Ain al-Baida, Mr Mohammad has not defected from the Syrian army. Originally from a village not far from this complex of abandoned buildings that houses the FSA fighters, Mr Mohammad says he spent April and May organising peaceful protests against President Bashar al-Assad’s regime.

In June, when the Syrian military’s infamous 4th Brigade came north, leaving a path of destruction in its wake, Mr Mohammad fled to Turkey, spending two months in a refugee camp near the border. But he grew tired of waiting, and returned to Syria to fight.

“People are dying in Syria,” he said. “No one came to help us. I did not accept what is happening. I can’t be patient, I prefer to die here.”

He is one of a growing number of civilians leaving their homes and joining the military defectors who make up the bulk of the FSA, a symbol of both the powerful hatred many ordinary Syrians feel towards the Assad regime and of how far the country has slid towards civil war.

Egypt and another day of martyrs

Al Jazeera — voice of the Arab spring

Mehdi Hasan writes: On Friday 11 February, thousands of Arabs spilled on to the streets of the Middle East’s capitals, from Rabat to Amman, to celebrate the downfall of the Egyptian dictator Hosni Mubarak. Doha, in the sleepy Gulf emirate of Qatar, was no different: hundreds of youths brought traffic to a standstill on the coastal Corniche Road. Shortly before midnight, some of them recognised one of the drivers stuck in the jam: the then Al Jazeera director general, Wadah Khanfar, who was on his way home from the network’s headquarters to grab a few hours sleep. After pulling him out of his car, dozens of Qataris queued up to hug and kiss him and thank him for his channel’s unrelenting, round-the-clock coverage of the uprisings in Cairo and Tunis.

“I wept,” recalls Khanfar, seven months later, when I meet him in the café of a central-London hotel. “I was very emotional.” He pauses. “In the Arab world, journalism really is an issue of life and death.”

He isn’t exaggerating. So far this year, Al Jazeera’s correspondents and producers across the Middle East have been harassed, arrested, beaten and, in the case of the cameraman Ali Hassan al-Jaber, killed (by pro-Gaddafi fighters in Libya). As Arab governments toppled from Tunisia to Egypt to Libya – and, last month, Yemen – Al Jazeera has been on hand to beam the pictures of ecstatic protesters, revolutionaries and rebels into the living rooms of ordinary Arabs across the region – and beyond. In Tunisia, the network picked up camera-phone footage from Facebook and other social-networking sites of the riots and protests that took place in the wake of the fruit-seller Mohamed Bouazizi’s self-immolation in December 2010, and gave them a regional prominence they otherwise would not have achieved.

In Egypt, for 18 days straight, Al Jazeera’s cameras broadcast live from Cairo’s Tahrir Square, giving a platform to the demonstrators, while documenting the violence of the Mubarak regime and its supporters.

“The protests rocking the Arab world this week have one thread uniting them: Al Jazeera,” the New York Times observed on 27 January, as it reported on how the channel’s coverage had “helped propel insurgent emotions from one capital to the next”. “They did not cause these events,” argued Marc Lynch, a professor of Middle East studies at George Washington University, “but it’s almost impossible to imagine all this happening without Al Jazeera.” Or, as a spokesman for WikiLeaks tweeted: “Yes, we may have helped Tunisia, Egypt. But let us not forget the elephant in the room: Al Jazeera + sat dishes.”

Two weeks in Bahrain’s military courts

Al Jazeera reports: Teachers, professors, politicians, doctors, athletes, students and others have all appeared in Bahrain’s military courts. In just two weeks, 208 people were sentenced or lost appeals, leading to a cumulative total of just less than 2,500 years in prison.

Many of those imprisoned took part in massive pro-democracy protests earlier this year. Others, families say, were in the wrong place at the wrong time and were targeted by virtue of their religious sect.

One lawyer, who represents dozens of the convicted and who asked not to be named, told Al Jazeera the total number of how many have stood in front of military courts is not clear – but he estimates at least 600. “Well over 1,000 people have been arrested since the crackdown began,” he said.

In an attempt to quell the uprising, the island’s rulers invited Saudi and other Gulf troops to Bahrain in March and called for a three-month state of emergency, or what it called the “National Safety Law”.

With the emergency law, came the military trials of hundreds of people in “National Safety Courts”. According to the lawyer, the courts were basically military courts, since both judge and general prosecutor were drawn from the military judicial system.

Death sentences were given out from trials that lasted less than two weeks. Many hearings lasted only a matter of minutes before verdicts were handed out. According to lawyers and defendants’ families, the main form of evidence in most cases were the confessions of the accused.

In Syria crisis, Turkey is caught between Iran and a hard place

Zvi Bar’el reports: “We have agreed that the free Syrian army will not carry out any independent attacks against the Syrian regime,” Ahmed Ramadan, one of the heads of the Syrian National Council, the chief opposition group, stated with satisfaction after meeting with the commander of the Free Syrian Army. “The commander of the free army, Col. Riyad al-Asad, agreed with us that the Syrian protest movement will continue to be a civilian movement and that the free army would open fire only to defend civilians or in cases of danger to life.”

It is not clear whether this agreement – arrived at last Wednesday during a secret meeting in Turkey – will last. It was the first such meeting between the National Council and the free Syrian army, which until now have not worked together, and it seems that the leaders are trying to set up a joint opposition council so that they can close ranks and offer a unified plan of action.

The fear of the National Council – which includes 200 opposition members led by Burhan Ghalioun, a Syrian intellectual living in Paris – is that wildcat attacks like the strike on the Air Force Intelligence base at Harasta near Damascus on November 17 and the attacks on Syrian army convoys, could play into the hands of the regime, which has been trying since the beginning of the uprising to prove that it is fighting a legitimate war against armed gangs.

Another concern is that the establishment of “a military arm” of the protest movement could eventually lead to an internal power struggle between different sections of the opposition and divert the struggle against the regime to the struggle between the various opposition groups.

Asad, an engineer and a member of the Syrian air force who defected to set up the free army at the end of July, now has 15,000 soldiers under his command. He is hoping for a leadership position in the new Syria.

The army he has put together has 11 battalions that are operating in large towns across Syria. Each one consists of companies that rely on local logistic assistance, plus weapons and equipment seized from Syrian army bases or imported from abroad.

According to Turkish and Syrian reports, large quantities of weapons were smuggled into Syria from Libya, via Turkey. Libyan rebels have reportedly also made the journey to Syria to partake in the uprising.

The New York Times reports: The seemingly routine flow of life in central Damascus could leave the impression that there is no crisis, or that the security approach is effective. Yet beneath the mundane, unease grips this capital as fear of civil war supplants hopes for a peaceful transition to democracy. Damascus residents describe the restive suburbs as severed from the city by government checkpoints, and while the security forces control those areas by day, the night belongs to the rebels. A request to visit the suburbs was denied “for your own safety” by a Syrian government official.

Protesters hold “flying demonstrations” inside the city, trying to subvert the control of security forces with a few people gathering briefly to be filmed shouting antigovernment slogans. Damascenes say that they have become so accustomed to hearing slogans chanted in the background, given the almost daily progovernment rallies organized by the government, that it takes a couple minutes to register that people are cursing President Assad. By the time they seek the source, the protesters have faded away.

Yet security forces seem omnipresent, usually materializing in minutes. Government critics say myriad supporters have been recruited into the shabiha, or ghosts, as the loyalist forces are known.

A recent flash demonstration near the central Cham Palace Hotel was dispersed by a group of waiters who flew out of a nearby cafe with truncheons, said an eyewitness. Many university campuses remain tense because student members of the ruling Baath Party have been reporting antigovernment classmates to the secret police.

Democracy and Islam in the Arab elections

Jack A. Goldstone writes: No doubt the most difficult task in the months ahead for Western leaders responding to changes in the Arab world will be to stick to their guns on democracy — that is, to accord elected governments and their leaders all the respect due to democratically chosen heads of state. This is because the elected governments will almost invariably be Islamist, hostile to Israel, and suspicious of the United States.

But really, what else could we expect? “Democratic” does not simply equate to pro-Western. If you tell people: “We have oppressed proponents of your historical religion for decades to create dictatorships for the sake of better relations with the West and Israel, and now we want you to choose your own government”, what else would people do than repudiate the pattern of the old dictatorships? And wouldn’t that repudiation more likely take the form of voting for well known and established parties that stood against the dictatorships, rather than for new parties with young faces that stand for such vague things as “secularism and liberalism?”

So let us start from the fact that an Islamist majority was always logically to be expected from free elections in Arab countries, and show no disappointment on that score. The crucial issue regarding the new regimes in Tunisia and Egypt is not that they are Islamist, but how will they act? How will they act toward other non-Islamist parties, and non-Islamic groups in society? How oppressive will they be toward women? How effective will they be on economic policy and science and technology? How will they manage popular hostility toward Israel? These are the issues that will determine the risks and success of these regimes.