Jane Mayer writes: Last spring, months before Wall Street was Occupied, civil disobedience of the kind sweeping the Arab world was hard to imagine happening here. But at Middlebury College, in Vermont, Bill McKibben, a scholar-in-residence, was leading a class discussion about Taylor Branch’s trilogy on Martin Luther King, Jr., and he began to wonder if the tactics that had won the civil-rights battle could work in this country again. McKibben, who is an author and an environmental activist (and a former New Yorker staff writer), had been alarmed by a conversation he had had about the proposed Keystone XL oil pipeline with James Hansen, the head of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, and one of the country’s foremost climate scientists. If the pipeline was built, it would hasten the extraction of exceptionally dirty crude oil, using huge amounts of water and heat, from the tar sands of Alberta, Canada, which would then be piped across the United States, where it would be refined and burned as fuel, releasing a vast new volume of greenhouse gas into the atmosphere. “What would the effect be on the climate?” McKibben asked. Hansen replied, “Essentially, it’s game over for the planet.”

It seemed a moment when, literally, a line had to be drawn in the sand. Crossing it, environmentalists believed, meant entering a more perilous phase of “extreme energy.” The tar sands’ oil deposits may be a treasure trove second in value only to Saudi Arabia’s, and the pipeline, as McKibben saw it, posed a powerful test of America’s resolve to develop cleaner sources of energy, as Barack Obama had promised to do in the 2008 campaign.

But TransCanada, the Canadian company proposing the project, was already two years into the process of applying for the necessary U.S. permit. The decision, which was expected by the end of this year, would ultimately be made by Obama, but, because the pipeline would cross an international border, the State Department had the lead role in evaluating the project, and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton had already indicated that she was “inclined” to approve it. Both TransCanada and the Laborers’ International Union of North America touted the construction jobs that the pipeline would create and the national-security bonus that it would confer by replacing Middle Eastern oil with Canadian.

The lineup promoting TransCanada’s interests was a textbook study in modern, bipartisan corporate influence peddling. Lobbyists ranged from the arch-conservative Grover Norquist’s Americans for Tax Reform to TransCanada’s in-house lobbyist Paul Elliott, who worked on both Hillary and Bill Clinton’s Presidential campaigns. President Clinton’s former Ambassador to Canada, Gordon Giffin, a major contributor to Hillary Clinton’s Presidential and Senate campaigns, was on TransCanada’s payroll, too. (Giffin says that he has never spoken to Secretary Clinton about the pipeline.) Most of the big oil companies also had a stake in the project. In a recent National Journal poll of “energy insiders,” opinion was virtually unanimous that the project would be approved.

Category Archives: capitalism

Lessons of the Luddites

Eliane Glaser writes: Two hundred years ago this month, groups of artisan cloth workers began to assemble at night on the moors around towns in Nottinghamshire. Proclaiming allegiance to the mythical King Ludd of Sherwood Forest, and sometimes subversively cross-dressed in frocks and bonnets, the Luddites organised machine-wrecking raids on textile factories that quickly spread across the north of England. The government mobilised the army and made frame breaking a capital offence: the uprisings were subdued by the summer of 1812.

Contrary to modern assumptions, the Luddites were not opposed to technology itself. They were opposed to the particular way it was being applied. After all, stocking frames had been around for 200 years by the time the Luddites came along, and they weren’t the first to smash them up. Their protest was specifically aimed at a new class of manufacturers who were aggressively undermining wages, dismantling workers’ rights and imposing a corrosive early form of free trade. To prove it, they selectively destroyed the machines owned by factory managers who were undercutting prices, leaving the other machines intact.

The original Luddites enjoyed strong local backing as well as high-profile support from Lord Byron and Mary Shelley, whose novel Frankenstein alludes to the industrial revolution’s dark side. But in the digital age, Luddism as a position is barely tenable. Just as we assume that the original Luddites were simply technophobes, it’s become unthinkable to countenance any broader political objections to contemporary technology’s direction of travel.

The promoters of internet technology combine visionary enthusiasm and like-it-or-not realism. So dissent is dismissed as either an irrational rejection of progress or a refusal to face the inevitable. It’s the realism that’s particularly hard to counter; the notion that technology is an unstoppable and non-negotiable force entirely separate from human agency. There’s not much time for political critique if you’re constantly being told that “the world is changing fast and you have to keep up”. Which is a bit rich given that politics infuses the arguments of even technology’s purest advocates.

As Slavoj Žižek has noted, the language of internet advocacy – phrases like “the unlimited flow of information” and “the marketplace of ideas” – mirrors the language of free-market economics. But techno-prophets also use the lingo of leftwing revolution. It’s there in books such as James Surowiecki’s The Wisdom of Crowds and Clay Shirky’s Here Comes Everybody, and in Vodafone’s slogan, “Power to You”; in the notion that blogs, Twitter and newspaper comment threads create a level playing field in the public debate; and it’s there in the countless magazine features about how the internet fosters grassroots protest, places the tools of cultural production in amateurs’ hands, and allows the little guy immediate access to information that keeps political leaders on their toes. This is not Adam Smith, it’s Marx and Mao.

In fact, both rhetorics – of the free market and of bottom-up emancipation – serve to conceal the rise of crony capitalism and the concentration of power and money at the top. Google is busily acquiring “all the world’s information”. Facebook is gathering our personal data for the coming world of personalised advertising. Amazon is monopolising the book trade. The abandonment of net neutrality means corporate control of the web. Once all our books, music, pictures and information are stored in the cloud, it will be owned by a handful of conglomerates.

Capitalism is the crisis

Poster by Favianna Rodriguez: “As a woman of color, and as a Latina working predominantly in spaces that affect la Raza, the current moment offers me the opportunity to talk about how Wall Street has affected our families. In case you didn’t see it, Pew Research center recently released a report on how Latino Household Wealth fell by 66% from 2005 to 2009. That means we lost 2/3 of our community’s assets! Now that’s an important reason why Latinos should care about the Occupy movement.”

Download this poster here [PDF].

The new progressive movement

Jeffrey Sachs writes: Twice before in American history, powerful corporate interests dominated Washington and brought America to a state of unacceptable inequality, instability and corruption. Both times a social and political movement arose to restore democracy and shared prosperity.

The first age of inequality was the Gilded Age at the end of the 19th century, an era quite like today, when both political parties served the interests of the corporate robber barons. The progressive movement arose after the financial crisis of 1893. In the following decades Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson came to power, and the movement pushed through a remarkable era of reform: trust busting, federal income taxation, fair labor standards, the direct election of senators and women’s suffrage.

The second gilded age was the Roaring Twenties. The pro-business administrations of Harding, Coolidge and Hoover once again opened up the floodgates of corruption and financial excess, this time culminating in the Great Depression. And once again the pendulum swung. F.D.R.’s New Deal marked the start of several decades of reduced income inequality, strong trade unions, steep top tax rates and strict financial regulation. After 1981, Reagan began to dismantle each of these core features of the New Deal.

Following our recent financial calamity, a third progressive era is likely to be in the making. This one should aim for three things. The first is a revival of crucial public services, especially education, training, public investment and environmental protection. The second is the end of a climate of impunity that encouraged nearly every Wall Street firm to commit financial fraud. The third is to re-establish the supremacy of people votes over dollar votes in Washington.

None of this will be easy. Vested interests are deeply entrenched, even as Wall Street titans are jailed and their firms pay megafines for fraud. The progressive era took 20 years to correct abuses of the Gilded Age. The New Deal struggled for a decade to overcome the Great Depression, and the expansion of economic justice lasted through the 1960s. The new wave of reform is but a few months old.

The young people in Zuccotti Park and more than 1,000 cities have started America on a path to renewal. The movement, still in its first days, will have to expand in several strategic ways. Activists are needed among shareholders, consumers and students to hold corporations and politicians to account. Shareholders, for example, should pressure companies to get out of politics. Consumers should take their money and purchasing power away from companies that confuse business and political power. The whole range of other actions — shareholder and consumer activism, policy formulation, and running of candidates — will not happen in the park.

The new movement also needs to build a public policy platform. The American people have it absolutely right on the three main points of a new agenda. To put it simply: tax the rich, end the wars and restore honest and effective government for all.

Finally, the new progressive era will need a fresh and gutsy generation of candidates to seek election victories not through wealthy campaign financiers but through free social media. A new generation of politicians will prove that they can win on YouTube, Twitter, Facebook and blog sites, rather than with corporate-financed TV ads. By lowering the cost of political campaigning, the free social media can liberate Washington from the current state of endemic corruption. And the candidates that turn down large campaign checks, political action committees, Super PACs and bundlers will be well positioned to call out their opponents who are on the corporate take.

Those who think that the cold weather will end the protests should think again. A new generation of leaders is just getting started. The new progressive age has begun.

Europe’s glaring democratic deficit

Larry Elliott writes: Financial markets rallied last week when the Greek prime minister, George Papandreou, announced he was dropping plans for a referendum on the terms of his country’s bailout. Bond dealers liked the idea that the government in Athens could soon be headed by Lucas Papademos, a former vice-president of the European Central Bank. Angela Merkel and Nicolas Sarkozy think Papademos is the sort of hard-line technocrat with whom they can do business.

Silvio Berlusconi’s long-predicted departure as Italy’s prime minister will no doubt be greeted in the same way, particularly if he is replaced by a government of national unity headed by another technocrat, Mario Monti. A former Brussels commissioner, he is seen as someone who could be relied upon to push through the European Union’s austerity programme during the next 12 months, watched over by Christine Lagarde’s team of officials from the International Monetary Fund.

From the perspective of the financial markets, this makes perfect sense. Papandreou could no longer be relied upon, and his decision to hold a plebiscite threw Europe into turmoil last week, blighting the Cannes G20 summit. He had to go.

In Italy, Berlusconi is seen as entirely the wrong man to cope with his country’s deepening crisis; bond yields are above 6.5%, a level that eventually resulted in bailouts for Greece, Ireland and Portugal. He, too, has to go in the interests not just of financial and political stability but to prevent the eurozone from imploding.

The European Union has always had problems with democracy, a messy process that can interfere with the grand designs of people at the top who know best. When Ireland voted no to the Nice Treaty, it was told to come up with the right result in a second ballot. The European Central Bank wields immense power, but nobody knows how the unelected members of its governing council vote because no minutes of meetings are published. That said, the latest phase of Europe’s sovereign debt crisis has exposed the quite flagrant contempt for voters, the people who are going to bear the full weight of the austerity programmes being cooked up by the political elites.

Here’s how things work. The real decisions in Europe are now taken by the Frankfurt Group, an unelected cabal made of up eight people: Lagarde; Merkel; Sarkozy; Mario Draghi, the new president of the ECB; José Manuel Barroso, the president of the European Commission; Jean-Claude Juncker, chairman of the Eurogroup; Herman van Rompuy, the president of the European Council; and Olli Rehn, Europe’s economic and monetary affairs commissioner.

This group, which is accountable to no one, calls the shots in Europe. The cabal decides whether Greece should be allowed to hold a referendum and if and when Athens should get the next tranche of its bailout cash. What matters to this group is what the financial markets think not what voters might want. To the extent that governments had any power, it has been removed and placed in the hands of the European Commission, the European Central Bank and the IMF. It is as if the democratic clock has been turned back to the days when France was ruled by the Bourbons.

In the circumstances, it is hardly surprising that electorates have resorted to general strikes and street protests to have their say. Governments come and go but the policies remain the same, creating a glaring democratic deficit. This would be deeply troubling even if it could be shown that the Frankfurt Group’s economic remedies were working, which they are not. Instead, the insistence on ever more austerity is pushing Europe’s weaker countries into an economic death spiral while their voters are being bypassed. That is a dangerous mixture.

The politics of austerity

Thomas B. Edsall writes: The conservative agenda, in a climate of scarcity, racializes policy making, calling for deep cuts in programs for the poor. The beneficiaries of these programs are disproportionately black and Hispanic. In 2009, according to census data, 50.9 percent of black households, 53.3 percent of Hispanic households and 20.5 percent of white households received some form of means-tested government assistance, including food stamps, Medicaid and public housing.

Less obviously, but just as racially charged, is the assault on public employees. “We can no longer live in a society where the public employees are the haves and taxpayers who foot the bills are the have-nots,” declared Scott Walker, the governor of Wisconsin.

For black Americans, government employment is a crucial means of upward mobility. The federal work force is 18.6 percent African-American, compared with 10.9 percent in the private sector. The percentages of African-Americans are highest in just those agencies that are most actively targeted for cuts by Republicans: the Department of Housing and Urban Development, 38.3 percent; the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, 42.4 percent; and the Education Department, 36.6 percent.

The politics of austerity are inherently favorable to conservatives and inhospitable to liberals. Congressional trench warfare rewards those most willing to risk all. Republicans demonstrated this in last summer’s debt ceiling fight, deploying the threat of a default on Treasury obligations to force spending cuts.

Conservatives are more willing to inflict harm on adversaries and more readily see conflicts in zero-sum terms — the basic framework of the contemporary debate. Once austerity dominates the agenda, the only question is where the ax falls.

Talk to Al Jazeera – Slavoj Zizek

Global day of rage: Hundreds of thousands march against inequity, big banks as occupy movement grows

From Buenos Aires to Toronto, Kuala Lumpur to London, hundreds of thousands of people rallied on Saturday in a global day of action against corporate greed and budget cutbacks, demanding better living conditions and a more equitable distribution of wealth and resources. Protests reportedly took place in 1,500 cities, including 100 cities in the United States — all in solidarity with the Occupy Wall Street movement that launched one month ago in New York City.

Charting inequality in America

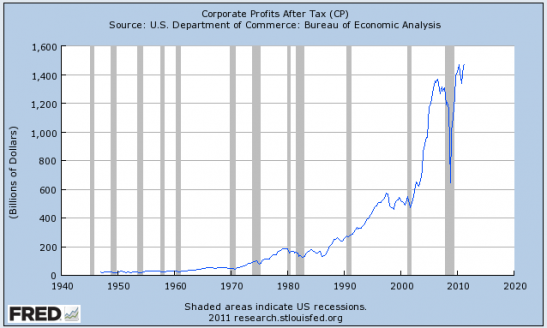

Henry Blodget writes: Inequality in this country has hit a level that has been seen only once in the nation’s history, and unemployment has reached a level that has been seen only once since the Great Depression. And, at the same time, corporate profits are at a record high.

In other words, in the never-ending tug-of-war between “labor” and “capital,” there has rarely—if ever—been a time when “capital” was so clearly winning.

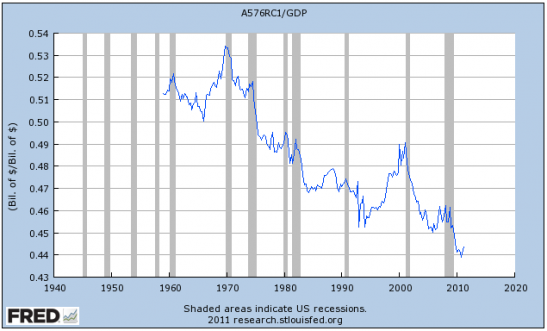

Wages as a percent of the US economy are the lowest they have ever been.

Corporate profits are at an all-time high

See 30 more charts tracking inequality in the United States.

A real challenge to corporate power

Interview with Arthur MacEwan, co-author of Economic Crisis, Economic Change: Getting to the Roots of the Crisis.

Wall Street is occupying our planet

Bill McKibben speaking at Occupy Wall Street at Washington Square Park on Saturday: Today in the New York Times there was a story that made it completely clear why we have to be here. They uncovered the fact that the company building that tar sands pipeline was allowed to choose another company to conduct the environmental impact statement, and the company that they chose was a company was a company that did lots and lots of work for them. So, in other words, the whole thing was rigged top to bottom and that’s why the environmental impact statement said that this pipeline would cause no trouble, unlike the scientists who said if we build this pipeline it’s “game over” for the climate. We can’t let this pipeline get built.

On November 6, one year before the election, we’re going to be in DC with a huge circle of people around the White House and they’re going to be carrying signs with quotations from Barack Obama from the 2008 campaign. He said, “It’s time to end the tyranny of oil.” He said, “I will have the most transparent government in history.” We have to go to DC to find out where they have locked that guy up. We have to free Obama, because there is some sort of stunt double there now. So on November 6, I hope we can move, just for a day, Occupy Wall Street down to the White House and get them in the fight against corporate power.

The reason that it’s so great that we’re occupying Wall Street is because Wall Street has been occupying the atmosphere. That’s why we can never do anything about global warming. Exxon gets in the way. Goldman Sachs gets in the way. The whole fossil fuel industry gets in the way. The sky does not belong to Exxon. They cannot keep using it as a sewer into which to dump their carbon. If they do, we’ve got no future and nobody else on this planet has a future.

I spend a lot of time in countries around the world organizing demonstrations and rallies in solidarity. In the last three years at 350.org, we’ve had 15,000 rallies in every country except North Korea. Everywhere around the world, poor people and black people and brown people and Asian people and young people are standing up. Most of those places, don’t produce that much carbon. They need us to act with them and for them, because the problem is 20 blocks south of here. That’s where the Empire lives and we’ve got to figure out how to tame it and make it work for this planet or not work at all.

Thank you guys very much.

If you want to live the American dream, move to Denmark

AlterNet reports: Americans may be deeply divided about what ails our country, but there’s no denying we’re a nation of unhappy campers.

Danes, on the other hand, consistently rank as some of the happiest people in the world, a fact attributed at least in part to Denmark’s legendary income equality and strong social safety net.

Forbes recently cited another possible factor; the Danes’ "high levels of trust." They trust each other, they trust ‘outsiders,’ they even trust their government. 90% of Danes vote. Tea party types dismiss Denmark as a hotbed of socialism, but really, they’re just practicing a more enlightened kind of capitalism.

In fact, as Richard Wilkinson, a British professor of social epidemiology, recently stated on PBS NewsHour, "if you want to live the American dream, you should move to Finland or Denmark, which have much higher social mobility."

While we debate whether climate change is real and a tax on unhealthy foods is nanny state social engineering, the Danish are actually trying to address these problems head on.

They can afford to, because they don’t spend all their waking hours worrying about whether they’re about to lose their job, or their house, or how they’re going to pay their student loans, or their health insurance premiums.

Did Steve Jobs take enough LSD?

An article in Time magazine has the headline: “Steve Jobs Had LSD. We Have the iPhone“.

I don’t have an iPhone, so I guess I can’t fairly pass judgment on how profound the experience might be — but I will anyway.

The idea that possessing an iPhone would be juxtaposed with a psychedelic experience highlights the extraordinary superficiality of the era in which we now live.

As I see all around me the stony faces of people staring into their indispensable iPhones, I’m not convinced Steve Jobs made this a better world.

In a New York Times op-ed a few days ago, Martin Lindstrom wrote:

Earlier this year, I carried out an fMRI experiment to find out whether iPhones were really, truly addictive, no less so than alcohol, cocaine, shopping or video games. In conjunction with the San Diego-based firm MindSign Neuromarketing, I enlisted eight men and eight women between the ages of 18 and 25. Our 16 subjects were exposed separately to audio and to video of a ringing and vibrating iPhone.

In each instance, the results showed activation in both the audio and visual cortices of the subjects’ brains. In other words, when they were exposed to the video, our subjects’ brains didn’t just see the vibrating iPhone, they “heard” it, too; and when they were exposed to the audio, they also “saw” it. This powerful cross-sensory phenomenon is known as synesthesia.

But most striking of all was the flurry of activation in the insular cortex of the brain, which is associated with feelings of love and compassion. The subjects’ brains responded to the sound of their phones as they would respond to the presence or proximity of a girlfriend, boyfriend or family member.

In short, the subjects didn’t demonstrate the classic brain-based signs of addiction. Instead, they loved their iPhones.

Picking up on this “finding,” the Time article said:

The paradoxes of love have perhaps never been clearer than in our relationships with Apple products — the warm, fleshy desire we feel for such cold, hard, glassy objects. But Jobs knew how to inspire material lust. He knew that consumers want something that not only sparkles and awes, but also feels accessible, easy to use, an object with which we want to merge and to feel one and the same.

Not coincidentally, that’s how people describe the experience of taking psychedelic drugs. It feels profoundly artificial yet deeply real, both high-tech and earthy-crunchy, human and mystically divine — in a word, transcendent. Jobs had this experience. He said that taking LSD was one of the two or three most important things he’d ever done. “He said there were things about him that people who had not tried psychedelics — even people who knew him well, including his wife — could never understand,” John Markoff reported for the Times.

Jobs’ experimentation with psychedelics might be noteworthy, yet those taking note display a singular lack of interest in delving into the reasons he might attach such significance to this particular kind of drug-induced experience.

Anyone who has used psychedelics understands exactly why Jobs, like others, emphasized the ineffable nature of the experience, but as true as it might be to say, “you can’t know what it’s like without taking it,” the effort to construct verbal representations of something that cannot be verbalized is not a pointless exercise.

To start with, calling a psychedelic experience a drug-induced experience is itself a misleading reference point.

We live in a society where drug-taking — either recreationally or by prescription — has never been more commonplace. So the idea that psychedelics induce particular sensations, suggests that they are yet another tool for modulating feelings and that those feelings merely happen to be located at a rarely engaged point on the feeling spectrum.

Most striking however — and this would tend to apply to those psychedelic experiences occurring in a tranquil and natural setting — is the sense that this is not a drug-induced experience. In other words, although the drug throws open a previously invisible door which will close after just a few hours, while that door remains open the intrinsic capabilities of the human mind appear to have been unlocked revealing the indivisibility of perceiver, perception, and perceived. The gap between “in here” and “out there” has dissolved.

The drug, rather than producing some form of intoxication, seems instead to peel away those perceptual filters that in everyday awareness largely shut out the world. For those rare individuals in whom those filters have already fallen away, the drug has no effect. Neem Karoli Baba, who Jobs had hoped to meet in India, had already demonstrated such an immunity to the effects of psychedelics. But the conclusion of Jobs own brief spiritual adventure was that individuals such as that particular Indian sage had much less to offer the world than the likes of Thomas Edison.

How did Jobs interpret his own LSD experience? I can only speculate, but given his role in helping create a society where our electronic connections often seem stronger than our physical relationships, I’m inclined to think that either he couldn’t retrieve much from the depths afterwards or didn’t penetrate any more deeply than the level of aesthetics. Later, when invited to support scientific research into therapeutic applications for psychedelics, Jobs declined.

The response to Jobs’ death has become a kind of instant beatification. He has become America’s greatest inventor — even though he didn’t invent anything. He is the visionary who shaped the world we live in — but is successfully developing products that cater to manufactured needs really a vision? What’s hard to dispute is that he was one of the greatest salesmen who ever lived.

This was a man who when asked whether he was glad that he had kids, said, “It’s 10,000 times better than anything I’ve ever done,” yet it seems he never found enough time to get to know them. “I wasn’t always there for them, and I wanted them to know why and to understand what I did,” said Jobs when explaining why he consented to having his biography written.

And therein lies the paradox of the age of global connectivity: it allows us to be part of ever expanding information and social networks which are formed by tying together bubbles of increasing isolation.

The 1%: Why CEOs who under-perform get over-payed

The Washington Post reports: As the board of Amgen convened at the company’s headquarters in March, chief executive Kevin W. Sharer seemed an unlikely candidate for a raise.

Shareholders at the company, one of the nation’s largest biotech firms, had lost 3 percent on their investment in 2010 and 7 percent over the past five years. The company had been forced to close or shrink plants, trimming the workforce from 20,100 to 17,400. And Sharer, a 63-year-old former Navy engineer, was already earning lots of money — about $15 million in the previous year, plus such perks as two corporate jets.

The board decided to give Sharer more. It boosted his compensation to $21 million annually, a 37 percent increase, according to the company reports.

Why?

The company board agreed to pay Sharer more than most chief executives in the industry — with a compensation “value closer to the 75th percentile of the peer group,” according to a 2011 regulatory filing.

This is how it’s done in corporate America. At Amgen and at the vast majority of large U.S. companies, boards aim to pay their executives at levels equal to or above the median for executives at similar companies.

The idea behind setting executive pay this way, known as “peer benchmarking,” is to keep talented bosses from leaving.

But the practice has long been controversial because, as critics have pointed out, if every company tries to keep up with or exceed the median pay for executives, executive compensation will spiral upward, regardless of performance. Few if any corporate boards consider their executive teams to be below average, so the result has become known as the “Lake Wobegon” effect.

Lifting the Veil: Obama and the Failure of Capitalist Democracy

Sit back — the following film is 1hr 53min long.

Stop snitchin: Fox News and Wall Street banks hustle to kill new whistleblower protections

Lee Fang reports: A few years go, a media firestorm erupted over the urban “Stop Snitchin” campaign promoted by gangs and a few hip hop icons. Stop Snitchin refers to the effort to intimidate informants to prevent them from cooperating with police about gang violence or drug trafficking schemes. Rapper Cam’ron received heavy scrutiny for endorsing the trend during an interview on the issue for CBS’s 60 Minutes.

A new Stop Snitchin campaign to deter would-be informants, in this case against people speaking up against crimes on Wall Street, is quietly taking shape, this time far from the media’s eye.

Financial experts and academics agree that strong whistleblower regulations could have prevented the Bernie Madoff Ponzi scheme and indeed much of the financial crisis if employees at firms engaged in fraudulent activity had spoken up early or had reported complex crimes to the appropriate authorities. Employees at firms at the center for the financial crisis, including troubled lender Countrywide, have cited intimidation and other illicit tactics as the reason few people spoke up as whistleblowers. Since the old whistleblower laws provided for weak legal protections for informants and relatively rare rewards, the Dodd-Frank financial reform law passed last year revamped the system with new rights for informants blowing the whistle on financial crimes.

Bank lobbyists and Fox News, however, have made such protections enemy number one.

Koch brothers flout law getting richer with secret Iran sales

Bloomberg reports:

In May 2008, a unit of Koch Industries Inc., one of the world’s largest privately held companies, sent Ludmila Egorova-Farines, its newly hired compliance officer and ethics manager, to investigate the management of a subsidiary in Arles in southern France. In less than a week, she discovered that the company had paid bribes to win contracts.

“I uncovered the practices within a few days,” Egorova- Farines says. “They were not hidden at all.”

She immediately notified her supervisors in the U.S. A week later, Wichita, Kansas-based Koch Industries dispatched an investigative team to look into her findings, Bloomberg Markets magazine reports in its November issue.

By September of that year, the researchers had found evidence of improper payments to secure contracts in six countries dating back to 2002, authorized by the business director of the company’s Koch-Glitsch affiliate in France.

“Those activities constitute violations of criminal law,” Koch Industries wrote in a Dec. 8, 2008, letter giving details of its findings. The letter was made public in a civil court ruling in France in September 2010; the document has never before been reported by the media.

Egorova-Farines wasn’t rewarded for bringing the illicit payments to the company’s attention. Her superiors removed her from the inquiry in August 2008 and fired her in June 2009, calling her incompetent, even after Koch’s investigators substantiated her findings. She sued Koch-Glitsch in France for wrongful termination.

Koch-Glitsch is part of a global empire run by billionaire brothers Charles and David Koch, who have taken a small oil company they inherited from their father, Fred, after his death in 1967, and built it into a chemical, textile, trading and refining conglomerate spanning more than 50 countries.

Koch Industries is obsessed with secrecy, to the point that it discloses only an approximation of its annual revenue — $100 billion a year — and says nothing about its profits.

Occupy Wall Street ends capitalism’s alibi

Richard Wolff writes:

Occupy Wall Street has already weathered the usual early storms. The kept media ignored the protest, but that failed to end it. The partisans of inequality mocked it, but that failed to end it. The police servants of the status quo over-reacted and that failed to end it – indeed, it fueled the fire. And millions looking on said, “Wow!” And now, ever more people are organising local, parallel demonstrations – from Boston to San Francisco and many places between.

Let me urge the occupiers to ignore the usual carping that besets powerful social movements in their earliest phases. Yes, you could be better organised, your demands more focused, your priorities clearer. All true, but in this moment, mostly irrelevant. Here is the key: if we want a mass and deep-rooted social movement of the left to re-emerge and transform the United States, we must welcome the many different streams, needs, desires, goals, energies and enthusiasms that inspire and sustain social movements. Now is the time to invite, welcome and gather them, in all their profusion and confusion.

The next step – and we are not there yet – will be to fashion the program and the organisation to realise it. It’s fine to talk about that now, to propose, debate and argue. But it is foolish and self-defeating to compromise achieving inclusive growth – now within our reach – for the sake of program and organisation. The history of the US left is littered with such programs and organisations without a mass movement behind them or at their core.

So permit me, in the spirit of honoring and contributing something to this historic movement, to propose yet another dimension, another item to add to your agenda for social change. To achieve the goals of this renewed movement, we must finally change the organisation of production that sustains and reproduces inequality and injustice. We need to replace the failed structure of our corporate enterprises that now deliver profits to so few, pollute the environment we all depend on, and corrupt our political system.

We need to end stock markets and boards of directors. The capacity to produce the goods and services we need should belong to everyone – just like the air, water, healthcare, education and security on which we likewise depend. We need to bring democracy to our enterprises. The workers within and the communities around enterprises can and should collectively shape how work is organised, what gets produced, and how we make use of the fruits of our collective efforts.

If we believe democracy is the best way to govern our residential communities, then it likewise deserves to govern our workplaces. Democracy at work is a goal that can help build this movement.