Ars Technica reports: Will government surveillance finally become a political issue for middle-class Americans?

Until recently, average Americans could convince themselves they were safe from government snooping. Yes, the government engaged in warrantless wiretaps, but those were directed at terrorists. Yes, movies and TV shows featured impressive technology, with someone’s location highlighted in real time on a computer screen, but such capabilities were used only to track drug dealers and kidnappers.

Figures released earlier this month should dispel that complacency. It’s now clear that government surveillance is so widespread that the chances of the average, innocent person being swept up in an electronic dragnet are much higher than previously appreciated. The revelation should lead to long overdue legal reforms.

The new figures, resulting from a Congressional inquiry, indicate that cell phone companies responded last year to at least 1.3 million government requests for customer data — ranging from subscriber identifying information to call detail records (who is calling whom), geolocation tracking, text messages, and full-blown wiretaps.

Almost certainly, the 1.3 million figure understates the scope of government surveillance. One carrier provided no data. And the inquiry only concerned cell phone companies. Not included were ISPs and e-mail service providers such as Google, which we know have also seen a growing tide of government requests for user data. The data released this month was also limited to law enforcement investigations—it does not encompass the government demands made in the name of national security, which are probably as numerous, if not more. And what was counted as a single request could have covered multiple customers. For example, an increasingly favorite technique of government agents is to request information identifying all persons whose cell phones were near a particular cell tower during a specific time period — this sweeps in data on hundreds of people, most or all of them entirely innocent.

How did we get to a point where communications service providers are processing millions of government demands for customer data every year? The answer is two-fold. The digital technologies we all rely on generate and store huge amounts of data about our communications, our whereabouts and our relationships. And since it’s digital, that information is easier than ever to copy, disclose, and analyze. Meanwhile, the privacy laws that are supposed to prevent government overreach have failed to keep pace. The combination of powerful technology and weak standards has produced a perfect storm of privacy erosion. [Continue reading…]

Category Archives: civil liberties

Don’t believe the Skype: it may not be as private as you might think

Dan Gillmor writes: When Skype became popular just under a decade ago, I repeatedly asked the company a question that I considered crucial. The online calling and messaging service encrypted users’ communications, and it was based outside the United States. But the encryption methods were kept secret, so outside researchers couldn’t verify their quality – a technique that experts in the field sometimes deride as “security through obscurity” – and I wanted to know whether Skype had a software backdoor that it or anyone else could use to listen into users’ calls. I was repeatedly given a non-denial denial – that is, an assurance that the information was being encrypted but no guarantee beyond that. So I assumed that Skype shouldn’t be considered a foolproof way to have an absolutely private conversation.

That assumption grew firmer when eBay bought Skype in 2005, putting Skype under American legal jurisdiction at a time when the Bush administration was routinely and illegally spying on citizens’ communications and Congress was a partner in destroying civil liberties. Moreover, eBay had a reputation for giving law enforcement just about anything it requested under just about any pretext.

Washington’s attitudes are, if anything, more police-statish than before. The Republicans don’t believe in any restraints on police, while Democrats who hated the Bush policies are supine now that the Obama administration has, if anything, expanded on the worst of the prior administration’s practices. And Skype now is part of Microsoft. So I am yawning at a spate of reports, most recently in the Washington Post, that Microsoft is giving law enforcement what torture fans might call “enhanced access” to Skype users’ conversations. The company’s statement on the matter says no recent changes have been made; but Skype also says this: “Skype takes appropriate organisational and technical measures to protect your information within our control with due observance of the applicable obligations and exceptions under the relevant law.”

To be clear, I don’t know one way or the other whether Skype has been secretly helping police and security officials listen in on conversations. I do know that the company, as in its statement above, persists in giving non-answers to the question. [Continue reading…]

Is CISPA, SOPA 2.0? The new cybersecurity bill explained

By Megha Rajagopalan, ProPublica, April 26, 2012

Update (4/27): The House of Representatives passed the bill on Thursday by 248-168, with 42 Democrats joining 206 Republicans in backing the measure.

Update (4/26): An earlier version of this story said a proposed amendment by Rep. Adam Schiff, D-Calif., had helped gain support for CISPA. Schiff’s amendment, which among other things would further define what’s considered a “cyber threat,” is no longer scheduled for consideration.

The Cyber Intelligence Sharing and Protection Act, up for debate in the House of Representatives today, has privacy activists, tech companies, security wonks and the Obama administration all jousting about what it means 2013 not only for security but Internet privacy and intellectual property. Backers expect CISPA to pass, unlike SOPA, the Stop Online Piracy Act that melted down amid controversy earlier this year.

Here’s a rundown on the debate and what CISPA could mean for Internet users.

What exactly is CISPA?

The act, sponsored Rep. Mike Rogers, R-Mich., and Rep. Dutch Ruppersberger, D-Md., would make it easier for private corporations and U.S. agencies, including military and intelligence, to share information related to “cyber threats.” In theory, this would enable the government and companies to keep up-to-date on security risks and protect themselves more efficiently. CISPA would amend the National Security Act of 1947, which currently contains no reference to cyber security. Companies wouldn’t be required to share any data. They would just be allowed to do so.

Why should I care?

CISPA could enable companies like Facebook and Twitter, as well as Internet service providers, to share your personal information with the National Security Agency and the CIA, as long as that information is deemed to pertain to a cyber threat or to national security.

How does the bill define “cyber threat”?

The bill itself defines it as information “pertaining to a vulnerability of” a system or network 2014 a definition that opponents have criticized as too broad. The bill gained support after sponsors agreed to allow votes on several amendments they said would make concessions to privacy activists; one aims to narrow the definition of “cyber threat.”

When can data be shared?

Rogers said the amended version of the bill would only enable companies and intelligence agencies to share information related to 1) cyber security purposes; 2) investigation and prosecution of cyber security crimes; 3) protection of individuals from death and bodily harm; 4) child pornography; or 5) protection of the national security of the United States.

Why are privacy activists upset about CISPA?

Privacy activists like the American Civil Liberties Union and the Electronic Frontier Foundation contend CISPA isn’t specific enough about just what constitutes a “cyber threat.” They say it enables Internet companies and service providers to hand over sensitive user information to intelligence agencies without enough oversight from the civilian side of government. Finally, they say it does not explicitly require Internet companies to remove identifying information about users before sharing. Opponents contend, for instance, that Facebook or Twitter could share user messages with the NSA or FBI without redacting the user’s name or personal details.

CISPA also protects the private sector from liability even if they share private user information, as long as that information is deemed to have been shared for cybersecurity or national security purposes. Even though sharing is voluntary and not required under the law, privacy activists say the legal immunity CISPA provides would make it easy for the government to pressure Internet companies to give up user data.

What kind of information can be shared?

Private companies and government agencies can share any information that pertains to a “cyber threat” or that would endanger national security. That could include user information, emails, and direct messages. Companies would be allowed to share with each other as well as the government. The government is not allowed to proactively search company-provided information for purposes unrelated to cyber security, but opponents say this would be tough to enforce. The bill does not place any explicit limit on how long that information can be kept. Several proposed amendments would limit the amount and kinds of information that can be shared, but it remains to be seen which 2014 if any 2014 will be adopted.

Is CISPA basically SOPA 2.0?

No, it’s very different.

SOPA was about intellectual property; CISPA is about cyber security, but opponents believe both bills have the potential to trample constitutional rights. The comparisons to SOPA stem from language in an earlier version of CISPA that referenced intellectual property. That wording was removed early on in response to mounting criticism. SOPA would have strengthened copyright laws, barring search engines and other websites from linking to sites that violated intellectual property regulations. That prompted a First Amendment concern from critics that it would give government the power to block websites wholesale, trampling free speech. CISPA’s liability shield, on the other hand, has sparked a concern based on the Fourth Amendment, which protects against unreasonable search and seizure. Opponents contend the law would make it too easy for private companies and the intelligence community to spy on users in the name of cyber security.

Why are some of the tech companies that protested SOPA, like Facebook and Microsoft, now supporting this bill?

CISPA gives Internet companies the ability to share threat information with intelligence agencies and receive information back from them, an ability they say would enable them to deal with cyber threats more effectively. It does not compel them to protect users’ privacy (though a variety of proposed amendments aim to add more stringent privacy protections). Companies could not be held liable for divulging a user’s identity or data to the government if the information relates to a “cyber threat.”

What’s the Obama administration’s take?

The White House is backing a Senate bill proposed by Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee Chairman Sen. Joe Lieberman, I-Conn., and has threatened to veto CISPA. Officials cite a lack of personal privacy protections. They say CISPA would enable military and intelligence agencies to take on a policing role on the internet, which the administration points out is a civilian sphere.

What is CISPA’s path forward in Congress?

A vote is set for Friday. CISPA has accumulated more than 100 cosponsors and will most likely pass the House. “This isn’t about scrambling to meet 218 votes, we are well past that,” co-sponsor Rogers said during a conference call with reporters. But the Senate is a different story 2014 there, it must compete with the Lieberman cyber security bill and one from Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz.

Would CISPA really make us more secure?

It’s unclear.

Some cyber security specialists note that neither CISPA nor other cyber security bills in Congress would compel companies to update software, hire outside specialists or take other measures to preemptively secure themselves against hackers and other threats. CISPA’s backers respond that the bill would forestall a “digital Pearl Harbor,” allowing a freer flow of information for a quicker and more effective response to hackers by both the government and the private sector.

Facebook and Google turned into government spies? The dangerous new law before Congress (CISPA)

Alternet reports: (Update: The Cyber Intelligence Sharing and Protection Act (CISPA) passed the House Thursday.)

The U.S. House of Representatives is expected to pass a reprehensible cyber-security bill that seeks to protect online companies—giant social media firms to data-sharing networks controlling utilities—from cyber attack. It is reprehensible because, as Democratic San Jose Rep. Zoe Lofgren said this week, it gives the federal government too much access to the private lives of every Internet user. Or as Libertarian Rep. Ron Paul also bluntly put it, it turns Facebook and Google into “government spies.”

But that’s not the biggest problem with the Congress’s urge to address a real problem—protecting the Internet from cyber attacks. While House passage launches a process that continues in the Senate, the bigger problem with the best known of the cyber bills before the House, CISPA, the Cyber Intelligence Sharing and Protection Act, is not what is in it — which is troubling enough — but what is not on Congress’s desk: a comprehensive approach to stop basic constitutional rights from eroding in the Internet Age.

“I don’t think the current cyber-security debate is adequately protecting civil liberties,” said Anjali Dalal, a resident fellow with the Information Society Project at Yale Law School (and a blogger). “CISPA seems to place constitutionally suspect behavior outside of judicial review. The bill immunizes all participating entities ‘acting in good faith.’ So what happens when an ISP hands over mountains of data under the encouragement and appreciation of the federal government? We can’t sue the government, because they didn’t do anything. And we can’t sue the ISP because the bill forbids it.”

What happens is anybody’s guess. But what does not happen is clear. The government, as with the recently adopted National Defense Authorization Act of 2012, does not have to go through the courts when fighting state "enemies" on U.S. soil. Instead, CISPA, like NDAA, expands extra-judicial procedures as if America’s biggest threats must always be addressed on a kind of wartime footing. Constitutional protections, starting with privacy rights, are mostly an afterthought. [Continue reading…]

39 ways to limit free speech

David Cole writes: Google “39 Ways to Serve and Participate in Jihad” and you’ll get over 590,000 hits. You’ll find full-text English language translations of this Arabic document on the Internet Archive, an Internet library; on 4Shared Desktop, a file-sharing site; and on numerous Islamic sites. You will find it cited and discussed in a US Senate Committee staff report and Congressional testimony. Feel free to read it. Just don’t try to make your own translation from the original, which was written in Arabic in Saudi Arabia in 2003. Because if you look a little further on Google you will find multiple news accounts reporting that on April 12, a 29-year old citizen from Sudbury, Massachusetts named Tarek Mehanna was sentenced to seventeen and a half years in prison for translating “39 Ways” and helping to distribute it online.

As Anthony Lewis was wont to ask in his New York Times columns, “Is this America?” Seventeen and a half years for translating a document? Granted, it’s an extremist text. Among the “39 ways” it advocates include “Truthfully Ask Allah for Martyrdom,” “Go for Jihad Yourself,” “Giving Shelter to the Mujahedin,” and “Have Enmity Towards the Disbelievers.” (Other “ways to serve,” however, include, “Learn to Swim and Ride Horses,” “Get Physically Fit,” “Stand in Opposition to the Disbelievers,” and “Expose the Hypocrites and Traitors.”) But surely we have not come to the point where we lock people up for nearly two decades for translating a widely available document? After all, news organizations and scholars routinely translate and publicize jihadist texts; think, for example, of the many reports about messages from Osama bin Laden.

In 2009, Tarek Mehanna, who has no prior criminal record, was arrested and placed in maximum security confinement on “terrorism” charges. The case against him rested on allegations that as a 21-year old he had traveled with friends to Yemen in 2004 in an unsuccessful search for a jihadist training camp in order to fight in Iraq, and that he had translated several jihadist tracts and videos into English for distribution on the Internet, allegedly to spur readers on to jihad. After a two-month trial, he was convicted of conspiring to provide material support to a terrorist organization. The jury did not specify whether it found him guilty for his aborted trip to Yemen—which resulted in no known contacts with jihadists—or for his translations, so under established law, the conviction cannot stand unless it’s permissible to penalize him for his speech. Mehanna is appealing.

Under traditional (read “pre-9/11”) First Amendment doctrine, Mehanna could not have been convicted even if he had written “39 Ways” himself, unless the government could shoulder the heavy burden of demonstrating that the document was “intended and likely to incite imminent lawless action,” a standard virtually impossible to meet for written texts. In 1969, in Brandenburg v. Ohio, the Supreme Court established that standard in ruling that the First Amendment protected a Ku Klux Klansman who made a speech to a Klan gathering advocating “revengeance” against “niggers” and “Jews.” It did so only after years of experience with federal and state governments using laws prohibiting advocacy of crime as a tool to target political dissidents (anarchists, anti-war protesters, and Communists, to name a few).

But in Mehanna’s case, the government never tried to satisfy that standard. It didn’t show that any violent act was caused by the document or its translation, much less that Mehanna intended to incite imminent criminal conduct and was likely, through the translation, to do so. In fact, it accused Mehanna of no violent act of any kind. Instead, the prosecutor successfully argued that Mehanna’s translation was intended to aid al-Qaeda, by inspiring readers to pursue jihad themselves, and therefore constituted “material support” to a “terrorist organization.” [Continue reading…]

Why I’m suing the U.S. government to protect internet freedom

Birgitta Jónsdóttir writes: Freedom for most people is something sacred, and many have been willing to sacrifice their lives for it. It is not just another word, for we measure the health of our democracies by the standard of freedom. We use it to measure our happiness and prosperity. Sadly, freedom of information, expression and speech is being eroded gradually without people paying much attention to it. Freedom of movement is permitted within certain zones, freedom of reading is disappearing, and the right to privacy is dwindling with the increased surveillance of our every move.

When the world wide web came into being, it was an unrestricted, free flowing world of creativity, connectivity and close encounters of the internet kind. It was as if the collective consciousness had taken on material (yet virtual!) form and people soon learned to use it to work, play and gather. Today’s social and democratic reform is born and bred online where people can freely exchange views and knowledge. Some of us old-school internet freedom fighters understood this value way before the web became such a part of our daily lives. One of them is John Perry Barlow, who in 1996 wrote a Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace in a response to an attempt to legalise restrictions on this brand new world. In it he declares: “Governments of the industrial world, you weary giants of flesh and steel, I come from Cyberspace, the new home of mind. On behalf of the future, I ask you of the past to leave us alone. You are not welcome among us. You have no sovereignty where we gather.”

Barlow inspired me and others to create the Icelandic Modern Media Initiative (IMMI), a parliamentary proposal unanimously approved by the Icelandic parliament in 2010, tasking the government to make Iceland a safe haven for freedom of information and expression, where privacy online would be as sacred and guarded as it is in the real world. The spirit of IMMI is in stark contrast with the serious attacks we are currently faced with. We have legal monsters like Acta, Sopa, Pipa and now Cispa; we have anti-terrorist acts abused to tear these liberties apart; we have armies of corporate lawyers scrutinising every bit of news prior to it getting out to us before we ever get to know the real stories that should remain in the public domain.

How Britain destroyed the father of computer science

One hundred years ago the father of computing was born. As one of the most influential men of the 20th century, Alan Turing’s name should be as well known as Einstein’s, yet rather than being showered with honors in his lifetime, he suffered the abuse of state brutality guided by the prevailing bigotry of that era.

Neurobonkers writes: Radiolab have done a fantastic twenty-minute podcast (MP3) on Alan Turing, the man who cracked the Enigma – arguably the pinnacle moment leading to the victory of the Allies in the Second World War.

While alive, Turing was never thanked or given acknowledgement for his work but instead suffered suffered a tragic, brutal blow in 1952 when he was arrested for homosexuality. The court ordered Turing to be “cured” with massive doses of Estrogen. The untested experiment resulted in Turing suffering a range of humiliating symptoms which if anything, had the opposite of their intended effect, Turing certainly didn’t turn around and decide to stop being homosexual. To put this abuse in context, Estrogen therapy is today used as a part of male-to-female transgender medical procedures (as well as for female contraceptives).

The side effects were not the worst problem from Turing’s perspective. Turing feared that his work would be dismissed by his peers, he was correct. Turing was sacked from his job at GCHQ and barred from discussing his cryptographic work. Turing killed himself two years after his conviction on 8th June 1954.

At the end of last year, the [British] Government was handed a petition for the pardon of Alan Turing with 21,000 signatures. The government declined this February:

“A posthumous pardon was not considered appropriate as Alan Turing was properly convicted of what at the time was a criminal offence. He would have known that his offence was against the law and that he would be prosecuted. It is tragic that Alan Turing was convicted of an offence which now seems both cruel and absurd-particularly poignant given his outstanding contribution to the war effort. However, the law at the time required a prosecution and, as such, long-standing policy has been to accept that such convictions took place and, rather than trying to alter the historical context and to put right what cannot be put right, ensure instead that we never again return to those times”.

Turing’s treatment serves as a reminder that democracy is not always enlightened and the will of the people can be brutal.

Even now, in a country that recognizes some limited gay rights there is the bizarre spectacle of a popular movement “in defense” of marriage which claims that same-sex marriage threatens the institution of marriage. As a predominantly Republican movement, it makes me wonder whether most Republicans believe that without constitutional protection they are all at risk of becoming homosexuals. I also wonder why those who want to defend marriage are not focusing their attention on a much more obvious threat: divorce.

U.S. anti-terrorism law curbs free speech and activist work, court told

The Guardian reports: A group political activists and journalists has launched a legal challenge to stop an American law they say allows the US military to arrest civilians anywhere in the world and detain them without trial as accused supporters of terrorism.

The seven figures, who include ex-New York Times reporter Chris Hedges, professor Noam Chomsky and Icelandic politician and WikiLeaks campaigner Birgitta Jonsdottir, testified to a Manhattan judge that the law – dubbed the NDAA or Homeland Battlefield Bill – would cripple free speech around the world.

They said that various provisions written into the National Defense Authorization Bill, which was signed by President Barack Obama at the end of 2011, effectively broadened the definition of “supporter of terrorism” to include peaceful activists, authors, academics and even journalists interviewing members of radical groups.

Controversy centres on the loose definition of key words in the bill, in particular who might be “associated forces” of the law’s named terrorist groups al-Qaida and the Taliban and what “substantial support” to those groups might get defined as. Whereas White House officials have denied the wording extends any sort of blanket coverage to civilians, rather than active enemy combatants, or actions involved in free speech, some civil rights experts have said the lack of precise definition leaves it open to massive potential abuse.

Welcome to the United States of Orwell, Part 1: Our one last chance to preserve the Bill of Rights

Charles Hugh Smith writes: This Congress and President Obama have shredded the Bill of Rights. We have one last chance to restore the Founding Fathers’ bastion against a rogue Central State: the Bill of Rights.

“Everything that Richard Nixon did to me, for which he faced impeachment and prosecution, which led to his resignation, is now legal under the Patriot Act, the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, and the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA).” Daniel Ellsberg. Can Congress legalize tyranny by passing a law that says it can? Can Congress shred the Bill of Rights by passing a law that says it can? Well, Congress has passed such a law, and President Obama–the most effective Trojan Horse president in American history, a plutocrat dressed as a “progressive”– rushed to sign it on New Years Eve 2011 when nobody was looking.

This is not a partisan issue, though various flaks and toadies are attempting to make it so. Here is how the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) describes the NDAA:Indefinite Detention, Endless Worldwide War and the 2012 National Defense Authorization Act.

He signed it. We’ll fight it. President Obama signed the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) into law. It contains a sweeping worldwide indefinite detention provision. The dangerous new law can be used by this and future presidents to militarily detain people captured far from any battlefield. He signed it. Now, we have to fight it wherever we can and for as long as it takes.

This is why the U.S. is #47 in global press freedom rankings

As was reported last week, the United States is now #47 in the annual World Press Freedom Index produced by Reporters Without Borders — not exactly a position which squares with the oft self-applied label, “Leader of the free world”!

Gavin Aronsen reports: On Saturday, Occupy Oakland re-entered the national spotlight during a day-long effort to take over an empty building and transform it into a social center. Oakland police thwarted the efforts, arresting more than 400 people in the process, primarily during a mass nighttime arrest outside a downtown YMCA. That number included at least six journalists, myself included, in direct violation of OPD media relations policy that states “media shall never be targeted for dispersal or enforcement action because of their status.”

After an unsuccessful afternoon effort to occupy a former convention center, the more than 1,000 protesters elected to return to the site of their former encampment outside City Hall. On the way, they clashed with officers, advancing down a street with makeshift shields of corrugated metal and throwing objects at a police line. Officers responded with smoke grenades, tear gas, and bean bag projectiles. After protesters regrouped, they marched through downtown as police pursued and eventually contained a few hundred of them in an enclosed space outside a YMCA. Some entered the gym and were arrested inside.

As soon as it became clear that I would be kettled with the protesters, I displayed my press credentials to a line of officers and asked where to stand to avoid arrest. In past protests, the technique always proved successful. But this time, no officer said a word. One pointed back in the direction of the protesters, refusing to let me leave. Another issued a notice that everyone in the area was under arrest.

I wound up in a back corner of the space between the YMCA and a neighboring building, where I met Vivian Ho of the San Francisco Chronicle and Kristin Hanes of KGO Radio. After it became clear that we would probably have to wait for hours there as police arrested hundreds of people packed tightly in front of us, we maneuvered our way to the front of the kettle to display our press credentials once more.

When Hanes displayed hers, an officer shook his head. “That’s not an Oakland pass,” he told her. “You’re getting arrested.” (She had a press pass issued by San Francisco, but not Oakland, police.) Another officer rejected my credentials, and I began interviewing soon-to-be-arrested protesters standing nearby. About five minutes later, an officer grabbed my arm and zip-tied me. Around the same time, Ho—who did have official OPD credentials—was also apprehended.

U.S. government threatens free speech with calls for Twitter censorship

What so often gets forgotten about the nature of free speech is that its sole value lies in protecting the right of public communication for those organizations and individuals that governments would rather silence. Speech that is utterly inoffensive is never in need of protection.

At the Electronic Frontier Foundation, Jillian C. York and Trevor Timm write about the growing number of calls for Twitter to ban the accounts of America’s designated enemies.

In a December 14th article in the New York Times, anonymous U.S. officials claimed they “may have the legal authority to demand that Twitter close” a Twitter account associated with the militant Somali group Al-Shabaab. A week later, the Telegraph reported that Sen. Joe Lieberman contacted Twitter to remove two “propaganda” accounts allegedly run by the Taliban. More recently, an Israeli law firm threatened to sue Twitter if they did not remove accounts run by Hezbollah.

Twitter is right to resist. If the U.S. were to pressure Twitter to censor tweets by organizations it opposes, even those on the terrorist lists, it would join the ranks of countries like India, Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Syria, Uzbekistan, all of which have censored online speech in the name of “national security.” And it would be even worse if Twitter were to undertake its own censorship regime, which would have to be based upon its own investigations or relying on the investigations of others that certain account holders were, in fact, terrorists.

Let’s review the various calls for Twitter to censor their site and the possible causes of action: [Continue reading…]

The NDAA’s historic assault on American liberty

Jonathan Turley writes: President Barack Obama rang in the New Year by signing the NDAA law with its provision allowing him to indefinitely detain citizens. It was a symbolic moment, to say the least. With Americans distracted with drinking and celebrating, Obama signed one of the greatest rollbacks of civil liberties in the history of our country … and citizens partied in unwitting bliss into the New Year.

Ironically, in addition to breaking his promise not to sign the law, Obama broke his promise on signing statements and attached a statement that he really does not want to detain citizens indefinitely (see the text of the statement here).

Obama insisted that he signed the bill simply to keep funding for the troops. It was a continuation of the dishonest treatment of the issue by the White House since the law first came to light. As discussed earlier, the White House told citizens that the president would not sign the NDAA because of the provision. That spin ended after sponsor Senator Carl Levin (Democrat, Michigan) went to the floor and disclosed that it was the White House and insisted that there be no exception for citizens in the indefinite detention provision.

The latest claim is even more insulting. You do not “support our troops” by denying the principles for which they are fighting. They are not fighting to consolidate authoritarian powers in the president. The “American way of life” is defined by our constitution and specifically the bill of rights. Moreover, the insistence that you do not intend to use authoritarian powers does not alter the fact that you just signed an authoritarian measure. It is not the use but the right to use such powers that defines authoritarian systems.

The growing militarisation of police

Why did Lacoste try to suppress a Palestinian artist’s science fictional art project?

io9.com reports: Palestinian artist Larissa Sansour uses science fictional imagery to discuss her people’s stateless condition, so her work was always bound to cause some controversy. She’s done a host of short films playing with science fiction movie themes, and commenting on Middle Eastern politics.

But after Sansour’s “sci-fi photo series” Nation Estate became one of the finalists for the Lacoste Elysée Prize 2011 — a prestigious award that carries a payment of over $30,000 — the contest’s sponsor, Lacoste, insisted that her work be disqualified. (Yes, the company that makes those funny alligator shirts.) Sansour’s name was removed from the prize’s website, and the photos were removed from an upcoming issue of the magazine ArtReview.

The Nation Estate Project imagines the entire Palestinian people living in one giant high-rise building, sort of like a J.G. Ballard novel, with each floor representing a different city. It’s an offshoot of one of her science fictional short films. Sansour told the Daily Star:

I think the most shocking thing about this development, is that I didn’t apply for this prize… They nominated [me] only to revoke my nomination later on grounds that my work is ‘too pro-Palestinian.’

The Swiss gallery hosting the prize later issued a statement [PDF] explaining its decision to suspend the contest and disassociate itself from Lacoste’s choice:

The Musée de l’Elysée has based its decision on the private partner’s wish to exclude Larissa Sansour, one of the prize nominees. We reaffirm our support to Larissa Sansour for the artistic quality of her work and her dedication. The Musée de l’Elysée has already proposed to her to present at the museum the series of photographs “Nation Estate”, which she submitted in the framework of the contest.

For 25 years, the Musée de l’Elysée has defended with strength artists, their work, freedom of the arts and of speech. With the decision it has taken today, the Musée de l’Elysée repeats its commitment to its fundamental values.

Israel: Publishing in a country that has outlawed free speech

In its relentless slide towards outright fascism, Israel has imposed an effective prohibition on political debate around the issue of boycott, divestment and sanctions (BDS). At +972, Dimi Reider describes the effect of the new law by answering the question, What is +972‘s stance on BDS?

The simple answer is that we don’t have one. The website is a collective of authors, each of whom have their own opinions about BDS. Some oppose it, some support it; some, like yours truly, support the D but are not particularly fond of the BS. But unfortunately, our ability to freely discuss this key aspect of the fight against the occupation has been severely and deliberately crippled by recent legislation. We may still carry opinions on BDS; but outright calls for boycott, divestment and sanctions hold far too great a risk for our site – a risk we are not in the financial position to take. Since we are legally responsible for all content appearing on the website, this obligates us to erase outright calls, and only outright calls for BDS from the comment thread as well.

Here is how it works: In May 2011, the Knesset passed the notorious “Boycott Law”. The Boycott Law does not make it a criminal offence or even misdemeanour to call for boycott. Neither any of us, nor any of readers will go to jail for making such a call. But the law does allow anyone who feels they have been materially impaired by that hypothetical call to sue us for damages – without actually proving any damages were suffered. In other words, if a reader was to publish a comment explicitly calling for BDS, tomorrow the website could be slammed with a massive lawsuit by some other reader or a right-wing “lawfare” organisaton. Even if we won the case in the long run, the legal fees would have sunk us very quickly – our budget is minimal, not to say minute, and we have no assets we can liquify and throw into the fight.

Obama administration considers censoring Twitter

How dangerous can 140 characters be?

Apparently if those 140 characters are being fired onto the web through the Twitter account of al Shabib, Somalia’s militant jihadist movement, then the national security of the United States could be in jeopardy.

The New York Times reports:

American officials say they may have the legal authority to demand that Twitter close the Shabab’s account, @HSMPress, which had more than 4,600 followers as of Monday night.

The most immediate effect of the Obama administration’s threat appears to have been that @HSMPress (which has so far only made 114 tweets) has subsequently gained hundreds of new followers.

Is Twitter itself about to take a stand in defense of freedom of speech?

A company spokesman, Matt Graves, said [to a Times reporter] on Monday, “I appreciate your offer for Twitter to provide perspective for the story, but we are declining comment on this one.”

Last Wednesday, the New York Times reported from Nairobi in Kenya:

Somalia’s powerful Islamist insurgents, the Shabab, best known for chopping off hands and starving their own people, just opened a Twitter account, and in the past week they have been writing up a storm, bragging about recent attacks and taunting their enemies.

“Your inexperienced boys flee from confrontation & flinch in the face of death,” the Shabab wrote in a post to the Kenyan Army.

It is an odd, almost downright hypocritical move from brutal militants in one of world’s most broken-down countries, where millions of people do not have enough food to eat, let alone a laptop. The Shabab have vehemently rejected Western practices — banning Western music, movies, haircuts and bras, and even blocking Western aid for famine victims, all in the name of their brand of puritanical Islam — only to embrace Twitter, one of the icons of a modern, networked society.

On top of that, the Shabab clearly have their hands full right now, facing thousands of African Union peacekeepers, the Kenyan military, the Ethiopian military and the occasional American drone strike all at the same time.

But terrorism experts say that Twitter terrorism is part of an emerging trend and that several other Qaeda franchises — a few years ago the Shabab pledged allegiance to Al Qaeda — are increasingly using social media like Facebook, MySpace, YouTube and Twitter. The Qaeda branch in Yemen has proved especially adept at disseminating teachings and commentary through several different social media networks.

“Social media has helped terrorist groups recruit individuals, fund-raise and distribute propaganda more efficiently than they have in the past,” said Seth G. Jones, a political scientist at the RAND Corporation.

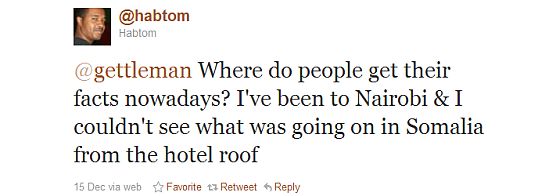

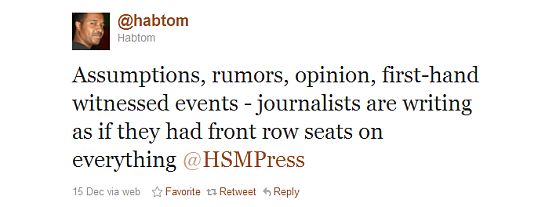

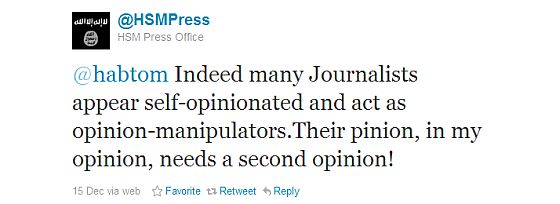

The Times reporter, Jeffrey Gettleman, sounds quite indignant that al Shabib should have the audacity to be using Twitter, so he can hardly have been surprised that his article prompted this exchange between @HSMPress and one of their followers:

Somalia is not the only front in the new war on Twitter.

The Washington Post reports on Twitter battles in Afghanistan:

U.S. military officials assigned to the International Security Assistance Force, or ISAF, as the coalition is known, took the first shot in what has become a near-daily battle waged with broadsides that must be kept to 140 characters.

“How much longer will terrorists put innocent Afghans in harm’s way,” @isafmedia demanded of the Taliban spokesman on the second day of the embassy attack, in which militants lobbed rockets and sprayed gunfire from a building under construction.

“I dnt knw. U hve bn pttng thm n ‘harm’s way’ fr da pst 10 yrs. Razd whole vilgs n mrkts. n stil hv da nrve to tlk bout ‘harm’s way,’ ” responded Abdulqahar Balkhi, one of the Taliban’s Twitter warriors, who uses the handle @ABalkhi….

U.S. military officials say the dramatic assault on the diplomatic compound convinced them that they needed to seize the propaganda initiative — and that in Twitter, they had a tool at hand that could shape the narrative much more quickly than news releases or responses to individual queries.

“That was the day ISAF turned the page from being passive,” said Navy Lt. Cmdr. Brian Badura, a military spokesman, explaining how @isafmedia evolved after the attack. “It used to be a tool to regurgitate the company line. We’ve turned it into what it can be.”

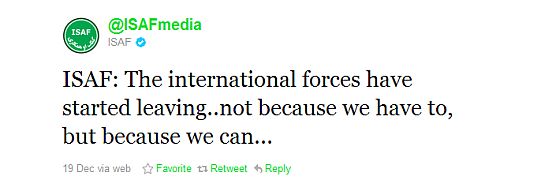

So how’s @isafmedia exploiting the power of Twitter? With tweets like this?

A we’re-winning-the-war tweet like this might sound good inside ISAF’s Twitter Command Center, but I don’t think it’s going to impress anyone else.

The problem the Obama administration is up against is not the threat posed by its adversaries on Twitter; it is that its own ventures into social media are predictably inept. Official tweets lack wit and tend to sound like the clumsy propaganda. But when losing an argument, the solution is not to look for ways to gag your opponent — that’s how dictators operate.

The Pentagon prides itself on its smart bombs. Can’t it come up with a few smart tweets?

U.S. anti-terrorism bill: Liberty vs security

Predator drones employed by U.S. police

The Los Angeles Times reports: Armed with a search warrant, Nelson County Sheriff Kelly Janke went looking for six missing cows on the Brossart family farm in the early evening of June 23. Three men brandishing rifles chased him off, he said.

Janke knew the gunmen could be anywhere on the 3,000-acre spread in eastern North Dakota. Fearful of an armed standoff, he called in reinforcements from the state Highway Patrol, a regional SWAT team, a bomb squad, ambulances and deputy sheriffs from three other counties.

He also called in a Predator B drone.

As the unmanned aircraft circled 2 miles overhead the next morning, sophisticated sensors under the nose helped pinpoint the three suspects and showed they were unarmed. Police rushed in and made the first known arrests of U.S. citizens with help from a Predator, the spy drone that has helped revolutionize modern warfare.

But that was just the start. Local police say they have used two unarmed Predators based at Grand Forks Air Force Base to fly at least two dozen surveillance flights since June. The FBI and Drug Enforcement Administration have used Predators for other domestic investigations, officials said.

“We don’t use [drones] on every call out,” said Bill Macki, head of the police SWAT team in Grand Forks. “If we have something in town like an apartment complex, we don’t call them.”

The drones belong to U.S. Customs and Border Protection, which operates eight Predators on the country’s northern and southwestern borders to search for illegal immigrants and smugglers. The previously unreported use of its drones to assist local, state and federal law enforcement has occurred without any public acknowledgment or debate.