Category Archives: social media

U.S. government looks to mine social media to combat terrorist attacks, uprisings

The Associated Press reports: The U.S. government is seeking software that can mine social media to predict everything from future terrorist attacks to foreign uprisings, according to requests posted online by federal law enforcement and intelligence agencies.

Hundreds of intelligence analysts already sift overseas Twitter and Facebook posts to track events such as the Arab Spring. But in a formal “request for information” from potential contractors, the FBI recently outlined its desire for a digital tool to scan the entire universe of social media — more data than humans could ever crunch.

The Department of Defense and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence also have solicited the private sector for ways to automate the process of identifying emerging threats and upheavals using the billions of posts people around the world share every day.

“Social media has emerged to be the first instance of communication about a crisis, trumping traditional first responders that included police, firefighters, EMT, and journalists,” the FBI wrote in its request. “Social media is rivaling 911 services in crisis response and reporting.”

The proposals already have raised privacy concerns among advocates who worry that such monitoring efforts could have a chilling effect on users. Ginger McCall, director of the open government project at the Washington, D.C.-based Electronic Privacy Information Center, said the FBI has no business monitoring legitimate free speech without a narrow, targeted law enforcement purpose.

“Any time that you have to worry about the federal government following you around peering over your shoulder listening to what you’re saying, it’s going to affect the way you speak and the way that you act,” McCall said.

Facebook is using you

Lori Andrews writes: Last week, Facebook filed documents with the government that will allow it to sell shares of stock to the public. It is estimated to be worth at least $75 billion. But unlike other big-ticket corporations, it doesn’t have an inventory of widgets or gadgets, cars or phones. Facebook’s inventory consists of personal data — yours and mine.

Facebook makes money by selling ad space to companies that want to reach us. Advertisers choose key words or details — like relationship status, location, activities, favorite books and employment — and then Facebook runs the ads for the targeted subset of its 845 million users. If you indicate that you like cupcakes, live in a certain neighborhood and have invited friends over, expect an ad from a nearby bakery to appear on your page. The magnitude of online information Facebook has available about each of us for targeted marketing is stunning. In Europe, laws give people the right to know what data companies have about them, but that is not the case in the United States.

Facebook made $3.2 billion in advertising revenue last year, 85 percent of its total revenue. Yet Facebook’s inventory of data and its revenue from advertising are small potatoes compared to some others. Google took in more than 10 times as much, with an estimated $36.5 billion in advertising revenue in 2011, by analyzing what people sent over Gmail and what they searched on the Web, and then using that data to sell ads. Hundreds of other companies have also staked claims on people’s online data by depositing software called cookies or other tracking mechanisms on people’s computers and in their browsers. If you’ve mentioned anxiety in an e-mail, done a Google search for “stress” or started using an online medical diary that lets you monitor your mood, expect ads for medications and services to treat your anxiety.

Ads that pop up on your screen might seem useful, or at worst, a nuisance. But they are much more than that. The bits and bytes about your life can easily be used against you. Whether you can obtain a job, credit or insurance can be based on your digital doppelgänger — and you may never know why you’ve been turned down.

Material mined online has been used against people battling for child custody or defending themselves in criminal cases. LexisNexis has a product called Accurint for Law Enforcement, which gives government agents information about what people do on social networks. The Internal Revenue Service searches Facebook and MySpace for evidence of tax evaders’ income and whereabouts, and United States Citizenship and Immigration Services has been known to scrutinize photos and posts to confirm family relationships or weed out sham marriages. Employers sometimes decide whether to hire people based on their online profiles, with one study indicating that 70 percent of recruiters and human resource professionals in the United States have rejected candidates based on data found online. A company called Spokeo gathers online data for employers, the public and anyone else who wants it. The company even posts ads urging “HR Recruiters — Click Here Now!” and asking women to submit their boyfriends’ e-mail addresses for an analysis of their online photos and activities to learn “Is He Cheating on You?”

Video: The impact of Twitter’s censorship plan

Twitter commits social suicide

What does Twitter call restrictions on free speech? They are “different ideas about the contours of freedom of expression.”

And what about censorship? It’s “the ability to reactively withhold content.”

Although I imagine George Orwell would have been adept at using this character-restricted medium, I also imagine he would have viewed it with contempt — and now even more so, as Twitter like every other corporate entity puts its commercial interests in front of everything else.

Mark Gibbs writes: In what can only have been a fit corporate insanity, Twitter announced that they have the ability to filter tweets to conform to the demands of various countries.

Thus, in France and Germany it is illegal to broadcast pro-Nazi sentiments and Twitter will presumably be able to block such content and inform the poster why it was blocked.

Quite obviously, Twitter’s management believe that there’s some kind of value in being able to filter in this way but given that over the course of 2011 the number of tweets per second (tps) ranged from a high of almost 9,000 tps down to just under 4,000 tps, any filtering has got to be computer-driven.

So, consider this tweet:

@FactsorDie Nazi Germany led the first public anti-smoking campaign.

Could that be considered to be pro-Nazi? How will a program accurately make that determination?

What concerns me is that if the algorithm Twitter uses registers a false positive (i.e. determines that the tweet is pro-Nazi when it isn’t) and the tweet has any time sensitivity to it then that attribute will be completely nullified by the time the tweet makes it out of tweet-jail if it ever does.

On the other hand if the software makes a false negative (i.e. determines that the tweet is NOT pro-Nazi when it is) then the filtering is useless and Twitter will be held accountable by every political group with an axe to grind.

Study reveals the Web isn’t as polarized as we thought

Farhad Manjoo writes: Today, Facebook is publishing a study that disproves some hoary conventional wisdom about the Web. According to this new research, the online echo chamber doesn’t exist.

This is of particular interest to me. In 2008, I wrote True Enough, a book that argued that digital technology is splitting society into discrete, ideologically like-minded tribes that read, watch, or listen only to news that confirms their own beliefs. I’m not the only one who’s worried about this. Eli Pariser, the former executive director of MoveOn.org, argued in his recent book The Filter Bubble that Web personalization algorithms like Facebook’s News Feed force us to consume a dangerously narrow range of news. The echo chamber was also central to Cass Sunstein’s thesis, in his book Republic.com, that the Web may be incompatible with democracy itself. If we’re all just echoing our friends’ ideas about the world, is society doomed to become ever more polarized and solipsistic?

It turns out we’re not doomed. The new Facebook study is one of the largest and most rigorous investigations into how people receive and react to news. It was led by Eytan Bakshy, who began the work in 2010 when he was finishing his Ph.D. in information studies at the University of Michigan. He is now a researcher on Facebook’s data team, which conducts academic-type studies into how users behave on the teeming network.

Bakshy’s study involves a simple experiment. Normally, when one of your friends shares a link on Facebook, the site uses an algorithm known as EdgeRank to determine whether or not the link is displayed in your feed. In Bakshy’s experiment, conducted over seven weeks in the late summer of 2010, a small fraction of such shared links were randomly censored—that is, if a friend shared a link that EdgeRank determined you should see, it was sometimes not displayed in your feed. Randomly blocking links allowed Bakshy to create two different populations on Facebook. In one group, someone would see a link posted by a friend and decide to either share or ignore it. People in the second group would not receive the link—but if they’d seen it somewhere else beyond Facebook, these people might decide to share that same link of their own accord.

By comparing the two groups, Bakshy could answer some important questions about how we navigate news online. Are people more likely to share information because their friends pass it along? And if we are more likely to share stories we see others post, what kinds of friends get us to reshare more often—close friends, or people we don’t interact with very often? Finally, the experiment allowed Bakshy to see how “novel information”—that is, information that you wouldn’t have shared if you hadn’t seen it on Facebook—travels through the network. This is important to our understanding of echo chambers. If an algorithm like EdgeRank favors information that you’d have seen anyway, it would make Facebook an echo chamber of your own beliefs. But if EdgeRank pushes novel information through the network, Facebook becomes a beneficial source of news rather than just a reflection of your own small world.

That’s exactly what Bakshy found. His paper is heavy on math and network theory, but here’s a short summary of his results. First, he found that the closer you are with a friend on Facebook—the more times you comment on one another’s posts, the more times you appear in photos together, etc.—the greater your likelihood of sharing that person’s links. At first blush, that sounds like a confirmation of the echo chamber: We’re more likely to echo our closest friends.

But here’s Bakshy’s most crucial finding: Although we’re more likely to share information from our close friends, we still share stuff from our weak ties—and the links from those weak ties are the most novel links on the network. Those links from our weak ties, that is, are most likely to point to information that you would not have shared if you hadn’t seen it on Facebook. The links from your close ties, meanwhile, more likely contain information you would have seen elsewhere if a friend hadn’t posted it. These weak ties “are indispensible” to your network, Bakshy says. “They have access to different websites that you’re not necessarily visiting.” [Continue reading…]

U.S. government threatens free speech with calls for Twitter censorship

What so often gets forgotten about the nature of free speech is that its sole value lies in protecting the right of public communication for those organizations and individuals that governments would rather silence. Speech that is utterly inoffensive is never in need of protection.

At the Electronic Frontier Foundation, Jillian C. York and Trevor Timm write about the growing number of calls for Twitter to ban the accounts of America’s designated enemies.

In a December 14th article in the New York Times, anonymous U.S. officials claimed they “may have the legal authority to demand that Twitter close” a Twitter account associated with the militant Somali group Al-Shabaab. A week later, the Telegraph reported that Sen. Joe Lieberman contacted Twitter to remove two “propaganda” accounts allegedly run by the Taliban. More recently, an Israeli law firm threatened to sue Twitter if they did not remove accounts run by Hezbollah.

Twitter is right to resist. If the U.S. were to pressure Twitter to censor tweets by organizations it opposes, even those on the terrorist lists, it would join the ranks of countries like India, Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Syria, Uzbekistan, all of which have censored online speech in the name of “national security.” And it would be even worse if Twitter were to undertake its own censorship regime, which would have to be based upon its own investigations or relying on the investigations of others that certain account holders were, in fact, terrorists.

Let’s review the various calls for Twitter to censor their site and the possible causes of action: [Continue reading…]

Israeli students to get $2,000 to spread state propaganda on Facebook

Ali Abunimah writes: The National Union of Israeli Students (NUIS) has become a full-time partner in the Israeli government’s efforts to spread its propaganda online and on college campuses around the world.

NUIS has launched a program to pay Israeli university students $2,000 to spread pro-Israel propaganda online for 5 hours per week from the “comfort of home.”

The union is also partnering with Israel’s Jewish Agency to send Israeli students as missionaries to spread propaganda in other countries, for which they will also receive a stipend.

This active recruitment of Israeli students is part of Israel’s orchestrated effort to suppress the Palestinian solidarity movement under the guise of combating “delegitimization” of Israel and anti-Semitism.

The involvement of the official Israeli student union as well as Haifa University, Tel Aviv University, Ben-Gurion University and Sapir College in these state propaganda programs will likely bolster Palestinian calls for the international boycott of Israeli academic institutions. [Continue reading…]

Internet finds voice as citizens cry freedom

Stratis G. Camatsos writes: July 1956: Writers, journalists, and students started a series of intellectual forums, called the Petőfi Circles, examining the problems facing Hungary. Later, in October 1956, university students in Szeged snubbed the official communist student union, which led to students of the Technical University to compile a list of 16-points containing several national policy demands. Days after, approximately 20,000 protesters convened organised by the writer’s union, which grew to 200,000 in front of the Parliament, all chanting the censored patriotic poem, the “National Song”.

December 1964: The Free Speech Movement (FSM) at the University of California at Berkeley was started by students who had participated in Mississippi’s ‘Freedom Summer’, and it provided an example of how students could bring about change through organisation. Later, in February 1965, the United States begins bombing North Vietnam. Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) organised marches on the Oakland Army Terminal, the departure point for many troops bound for Southeast Asia. In April 1965, between 15,000 and 25,000 people gathered at the capital, a turnout that surprised even the organisers.

December 2010: Mohamed Bouazizi proclaimed that there was police corruption and ill treatment in Tunisia. This sparked revolutions well into 2011 in Tunisia and Egypt, a civil war in Libya resulting in the fall of its government; civil uprisings in Bahrain, Syria, and Yemen, major protests in Algeria, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Morocco, and Oman, and less in Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, and Sudan.

The parallels between all three of these iconic uprisings are that the protests have shared techniques of civil response in sustained campaigns involving strikes, demonstrations, marches and rallies. All of them were based on a common ideal or symbol that led the way for organisation. All were themselves the epitome of the principle of freedom of expression.

The differences between the three rest with the tools used to mobilise and organise. As the former two were based on word of mouth and media such as newspapers and TV, the latter one saw the largest uprising to have used the social media to communicate and raise awareness in the face of state attempts at repression and Internet censorship. It was truly a behemothic moment for the internet, as its potential was finally reached. [Continue reading…]

#Riot: Self-organized, hyper-networked revolts — coming to a city near you

Bill Wasik writes: Let’s start with the fundamental paradox: Our personal technology in the 21st century—our laptops and smartphones, our browsers and apps—does everything it can to keep us out of crowds.

Why pack into Target when Amazon can speed the essentials of life to your door? Why approach strangers at parties or bars when dating sites like OkCupid (to say nothing of hookup apps like Grindr) can more efficiently shuttle potential mates into your bed? Why sit in a cinema when you can stream? Why cram into arena seats when you can pay per view? We declare the obsolescence of “bricks and mortar,” but let’s be honest: What we usually want to avoid is the flesh and blood, the unpleasant waits and stares and sweat entailed in vying against other bodies in the same place, at the same time, in pursuit of the same resources.

And yet: On those rare occasions when we want to form a crowd, our tech can work a strange, dark magic. Consider this anonymous note, passed around among young residents of greater London on a Sunday in early August:

Everyone in edmonton enfield woodgreen everywhere in north link up at enfield town station 4 o clock sharp!!!!

Bring some bags, the note went on; bring cars and vans, and also hammers. Make sure no snitch boys get dis, it implored. Link up and cause havic, just rob everything. Police can’t stop it. This note, and variants on it, circulated on August 7, the day after a riot had broken out in the London district of Tottenham, protesting the police killing of a 29-year-old man in a botched arrest. So the recipients of this missive, many of them at least, were already primed for violence.

It helped, too, that the medium was BlackBerry Messenger, a private system in which “broadcasting” messages—sending them to one’s entire address book—can be done for free, with a single command. Unlike in the US, where BlackBerrys are seen as strictly a white-collar accessory, teens and twentysomethings in the UK have embraced the platform wholeheartedly, with 37 percent of 16- to 24-year-olds using the devices nationwide; the percentage is probably much higher in urban areas like London. From early on in the rioting, BBM messages were pinging around among the participants and their friends, who were using the service for everything from sharing photos to coordinating locations. Contemplating the corporate-grade security and mass communication of the platform, Mike Butcher, a prominent British blogger who serves as a digital adviser to the London mayor, wryly remarked that BBM had become the “thug’s Gutenberg press.”

Are bloggers journalists?

Obama administration considers censoring Twitter

How dangerous can 140 characters be?

Apparently if those 140 characters are being fired onto the web through the Twitter account of al Shabib, Somalia’s militant jihadist movement, then the national security of the United States could be in jeopardy.

The New York Times reports:

American officials say they may have the legal authority to demand that Twitter close the Shabab’s account, @HSMPress, which had more than 4,600 followers as of Monday night.

The most immediate effect of the Obama administration’s threat appears to have been that @HSMPress (which has so far only made 114 tweets) has subsequently gained hundreds of new followers.

Is Twitter itself about to take a stand in defense of freedom of speech?

A company spokesman, Matt Graves, said [to a Times reporter] on Monday, “I appreciate your offer for Twitter to provide perspective for the story, but we are declining comment on this one.”

Last Wednesday, the New York Times reported from Nairobi in Kenya:

Somalia’s powerful Islamist insurgents, the Shabab, best known for chopping off hands and starving their own people, just opened a Twitter account, and in the past week they have been writing up a storm, bragging about recent attacks and taunting their enemies.

“Your inexperienced boys flee from confrontation & flinch in the face of death,” the Shabab wrote in a post to the Kenyan Army.

It is an odd, almost downright hypocritical move from brutal militants in one of world’s most broken-down countries, where millions of people do not have enough food to eat, let alone a laptop. The Shabab have vehemently rejected Western practices — banning Western music, movies, haircuts and bras, and even blocking Western aid for famine victims, all in the name of their brand of puritanical Islam — only to embrace Twitter, one of the icons of a modern, networked society.

On top of that, the Shabab clearly have their hands full right now, facing thousands of African Union peacekeepers, the Kenyan military, the Ethiopian military and the occasional American drone strike all at the same time.

But terrorism experts say that Twitter terrorism is part of an emerging trend and that several other Qaeda franchises — a few years ago the Shabab pledged allegiance to Al Qaeda — are increasingly using social media like Facebook, MySpace, YouTube and Twitter. The Qaeda branch in Yemen has proved especially adept at disseminating teachings and commentary through several different social media networks.

“Social media has helped terrorist groups recruit individuals, fund-raise and distribute propaganda more efficiently than they have in the past,” said Seth G. Jones, a political scientist at the RAND Corporation.

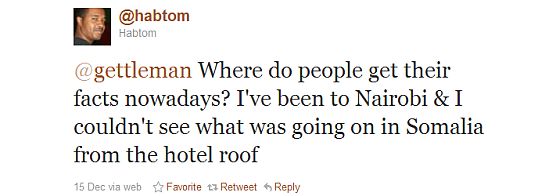

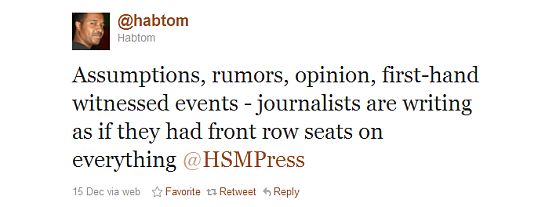

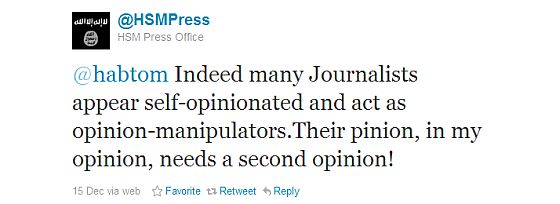

The Times reporter, Jeffrey Gettleman, sounds quite indignant that al Shabib should have the audacity to be using Twitter, so he can hardly have been surprised that his article prompted this exchange between @HSMPress and one of their followers:

Somalia is not the only front in the new war on Twitter.

The Washington Post reports on Twitter battles in Afghanistan:

U.S. military officials assigned to the International Security Assistance Force, or ISAF, as the coalition is known, took the first shot in what has become a near-daily battle waged with broadsides that must be kept to 140 characters.

“How much longer will terrorists put innocent Afghans in harm’s way,” @isafmedia demanded of the Taliban spokesman on the second day of the embassy attack, in which militants lobbed rockets and sprayed gunfire from a building under construction.

“I dnt knw. U hve bn pttng thm n ‘harm’s way’ fr da pst 10 yrs. Razd whole vilgs n mrkts. n stil hv da nrve to tlk bout ‘harm’s way,’ ” responded Abdulqahar Balkhi, one of the Taliban’s Twitter warriors, who uses the handle @ABalkhi….

U.S. military officials say the dramatic assault on the diplomatic compound convinced them that they needed to seize the propaganda initiative — and that in Twitter, they had a tool at hand that could shape the narrative much more quickly than news releases or responses to individual queries.

“That was the day ISAF turned the page from being passive,” said Navy Lt. Cmdr. Brian Badura, a military spokesman, explaining how @isafmedia evolved after the attack. “It used to be a tool to regurgitate the company line. We’ve turned it into what it can be.”

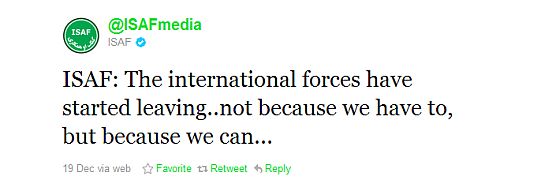

So how’s @isafmedia exploiting the power of Twitter? With tweets like this?

A we’re-winning-the-war tweet like this might sound good inside ISAF’s Twitter Command Center, but I don’t think it’s going to impress anyone else.

The problem the Obama administration is up against is not the threat posed by its adversaries on Twitter; it is that its own ventures into social media are predictably inept. Official tweets lack wit and tend to sound like the clumsy propaganda. But when losing an argument, the solution is not to look for ways to gag your opponent — that’s how dictators operate.

The Pentagon prides itself on its smart bombs. Can’t it come up with a few smart tweets?

Saudi prince invests $300 million in Twitter

Owning three percent of Twitter might not amount to a controlling stake, but when the Saudis start investing in social media you can bet that making money is not their only interest.

The New York Times reports: Prince Walid bin Talal of Saudi Arabia announced a $300 million stake in the social media site Twitter, as the billionaire expands his holdings in the United States.

The investment by Prince Walid and his investment company, Kingdom Holding, represents roughly 3 percent of the company. Prince Walid, who owns 95 percent of Kingdom Holding, said in a statement that the purchase was part of a strategy “to invest in promising, high-growth businesses with a global impact.”

With Twitter, Prince Walid — who also own stakes in American blue chip companies including Citigroup, General Motors and Apple — gains a foothold in the fast-growing social networking space. The microblogging service, which has more than 100 million active users, is part of an elite group of Internet companies that have rapidly attracted users in recent years and that have garnered multi-billion dollar valuations.

Twitter has been increasingly popular in the Arab world, where it was credited with playing a role in the recent uprisings across North Africa and the Gulf. Arabic is now the fastest growing language used on Twitter, according to the data intelligence company Semiocast. The volume of Arabic messages increased by 2,146 percent in the 12 months ending in October.

“We believe that social media will fundamentally change the media industry landscape in the coming years. Twitter will capture and monetize this positive trend,” Ahmed Reda Halawani, Kingdom Holding’s executive director of private equity and international investments, said in a statement.

#OWS: Movement surges 10% online since Zuccotti eviction

Micah Sifry writes: A week ago, early Tuesday morning November 15th, New York City police forcibly evicted the Occupy Wall Street protest encampment at Zuccotti Park. Since then, there’s been an interesting shift in how some key observers in the mainstream media talk about the movement. For example, David Carr, an influential media columnist for the New York Times, wrote yesterday as if the Occupy movement had essentially ended, with no recognition that there are still many other cities and campuses with physical occupations underway. “A tipping point is at hand,” he intoned about the movement, “now that it is not gathered around campfires.” He added, darkly, “When the spectacle disappears reporters often fold up their tents as well.”

Not to pick on Carr, whose column and work I often enjoy, but since when did reporters treat political movements like passing fads? The Times, like many other newspapers, has given plenty of coverage to the Tea Party movement–even when the available data suggested that the Tea Party had nowhere as big a following on the ground as its media presence and polling numbers suggested.

Interestingly enough, since last Tuesday’s eviction in NYC, support for the overall Occupy Wall Street movement has risen significantly online.

How the U.S. Justice Department legally hacked my Twitter account

Birgitta Jonsdottir, a member of Iceland’s Parliament, writes: Before my Twitter case, in which the US Department of Justice has demanded that the social media site hands over personal information about my account which it deems necessary to its investigation of WikiLeaks, I didn’t think much about what rights I would be signing off when accepting user agreement in my computer. The text is usually lengthy, in a legal language that most people don’t understand. Very few people read the user agreements, and very few understand their legal implications if someone in the real world would try to use one against them.

Many of us who use the internet – be it to write emails, work or browse its growing landscape: mining for information, connecting with others or using it to organise ourselves in various groups of the like-minded – are not aware of that our behavior online is being monitored. Profiling has become a default with companies such as Google and Facebook. These companies have huge databases recording our every move within their environment, in order to groom advertising to our interests. For them, we are only consumers to push goods at, in order to sell ads through an increasingly sophisticated business model. For them, we are not regarded as citizens with civic rights.

This notion needs to change. No one really knew where we were heading a few years ago: neither we the users, nor the companies harvesting our personal information for profit. Very few of us imagined that governments that claim to be democratic would invade our online privacy with no regard to the fundamental rights we are supposed to have in the real world. We might look to China and other stereotypical totalitarian states and expect them to violate the free flow of information and our digital privacy, but not – surely? – our very own democratically elected governments.

What I have learned about my lack of rights in the last few months is of concern for everyone who uses the internet and calls for actions to raise people’s awareness about their legal rights and ways to improve legal guidelines about digital media, be it locally or globally. The problem – and the dilemma we are facing – is that there are no proper standards, no basic laws in place that deal with the fundamental question: are we to be treated as consumers or citizens online? There is no international charter that says we should have the same civic rights as we have in the offline world.

Europe’s rising Facebook fascism

The Guardian reports: The far right is on the rise across Europe as a new generation of young, web-based supporters embrace hardline nationalist and anti-immigrant groups, a study [PDF] has revealed ahead of a meeting of politicians and academics in Brussels to examine the phenomenon.

Research by the British thinktank Demos for the first time examines attitudes among supporters of the far right online. Using advertisements on Facebook group pages, they persuaded more than 10,000 followers of 14 parties and street organisations in 11 countries to fill in detailed questionnaires.

The study reveals a continent-wide spread of hardline nationalist sentiment among the young, mainly men. Deeply cynical about their own governments and the EU, their generalised fear about the future is focused on cultural identity, with immigration – particularly a perceived spread of Islamic influence – a concern.

“We’re at a crossroads in European history,” said Emine Bozkurt, a Dutch MEP who heads the anti-racism lobby at the European parliament. “In five years’ time we will either see an increase in the forces of hatred and division in society, including ultra-nationalism, xenophobia, Islamophobia and antisemitism, or we will be able to fight this horrific tendency.”

The report comes just over three months after Anders Breivik, a supporter of hard right groups, shot dead 69 people at youth camp near Oslo. While he was disowned by the parties, police examination of his contacts highlighted the Europe-wide online discussion of anti-immigrant and nationalist ideas.

Data in the study was mainly collected in July and August, before the worsening of the eurozone crisis. The report highlights the prevalence of anti-immigrant feeling, especially suspicion of Muslims. “As antisemitism was a unifying factor for far-right parties in the 1910s, 20s and 30s, Islamophobia has become the unifying factor in the early decades of the 21st century,” said Thomas Klau from the European Council on Foreign Relations, who will speak at Monday’s conference.

Welcome to the “augmented revolution”

Nathan Jurgenson writes: Earlier this year, there was a spat that was both silly and superficial over the terms “Twitter” and “Facebook Revolution” to capture protests in the Arab World. On the one hand, those terms offensively reduced a vast political movement to a social networking site. On the other, Malcolm Gladwell’s response — that there was protest before social media, therefore social media had no role — was equally unfulfilling.

Neither view captured the way technology has been utilized in this global wave of dissent. We are witnessing political mobilizations across much of the globe, including the Middle East, North Africa, Asia and South America. Riots and “flash mobs” are increasingly making the news. In the United States the emergence of the Occupy movement shows that technology and our global atmosphere of dissent is the effective merging of the on- and offline worlds. We cannot only focus on one and ignore the other.

It is no historical coincidence that the rise of social media will be forever linked with the global spread of mass mobilizations of people in physical space that we are witnessing right now. Social media is not some space separate from the offline, physical world. Instead, social media should be understood as the effective merging of the digital and physical, the on- and offline, atoms and bits. And the consequences of this are erupting around us.

Occupy Wall Street and the subsequent occupation movements around the United States and increasingly the globe might best be called an augmented revolution. By “augmented,” I am referring to a larger conceptual perspective that views our reality as the byproduct of the enmeshing of the on- and offline. This is opposed to the view that the digital and physical are separate spheres, what I have called “digital dualism.” Research has demonstrated that sites like Facebook have everything to do with the offline. Our offline lives drive whom we are Facebook-friends with and what we post about. And what happens on Facebook influences how we experience life when we are not logged in and staring at some glowing screen (e.g., we are being trained to experience the world always as a potential photo, tweet, status update). Facebook augments our offline lives rather than replaces them. And this is why research shows that Facebook users have more offline contacts, are more civically engaged, and so on.

Jailed Egyptian blogger on hunger strike says ‘he is ready to die’

The Guardian reports: An Egyptian blogger jailed for criticising the country’s military junta has declared himself ready to die, as his hunger strike enters its 57th day.

“If the militarists thought that I would be tired of my hunger strike and accept imprisonment and enslavement, then they are dreamers,” said Maikel Nabil Sanad, in a statement announcing that he would boycott the latest court case against him, which began last Thursday. “It’s more honourable [for] me to die committing suicide than [it is] allowing a bunch of Nazi criminals to feel that they succeeded in restricting my freedom. I am bigger than that farce.”

Sanad, whom Amnesty International has declared to be a prisoner of conscience, was sentenced by a military tribunal in March to three years in jail after publishing a blog post entitled “The people and the army were never on one hand”. The online statement, which deliberately inverted a popular pro-military chant, infuriated Egypt’s ruling generals who took power after the ousting of former president Hosni Mubarak, and have since been accused of multiple human rights violations in an effort to shut down legitimate protest and stifle revolutionary change.

The 26-year-old was found guilty of “insulting the Egyptian army”. The case helped spark a nationwide opposition movement to military trials for civilians, and cast further doubt on the intentions of the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (Scaf), whose promises regarding Egypt’s post-Mubarak transition to democracy appear increasingly hollow.

In mid-September, Saki Knafo wrote: Nabil is not the only civilian to have undergone a military trial since the revolution. An article from the Pulitzer Center for Crisis Reporting places the total number at 12,000, and says that suspects have been typically tried in three or four days and have been given sentences of between a few months to several years.

Earlier this year, Asmaa Mahfouz, a prominent Egyptian activist, wrote the following Tweet (translated from Arabic): “If the judiciary does not get us our rights, don’t be upset if armed groups carry out a series of assassinations as there is neither law nor justice.”

She was brought before the military prosecutor last month and charged with insulting the military. The case became a flashpoint in the growing movement to end the military trials, with presidential candidates and political groups criticizing the decision. The military council eventually ordered that the charges be dropped.

But Nabil is different from Mahfouz. He isn’t a star, for one thing. “Maikel isn’t a prominent public figure,” his father told the press during a recent demonstration in support of his son. “Maikel is a normal person and that is why they imprisoned him. Others who had a lot of public support and had similar charges were released. But Maikel is one of the general public and he doesn’t have anyone to defend him.”

There’s also the fact that Nabil supports Israel. He says he objected to military conscription in the first place because he refused to “point a gun at an Israeli youth who is defending his country’s right to exist,” and a section of his website is in Hebrew.

Several organizations are again calling for his release. A statement from Reporters Without Borders observed that Nabil “could very soon die” and warned that he could become “the symbol of a repressive and unjust post-Mubarak Egypt.”

In response, a military official was quoted as saying that what Nabil wrote on his blog was “a clear transgression of all boundaries of insult and libel.”

In April, shortly after Nabil’s arrest, a friend of Nabil’s and fellow blogger wrote an email to The Huffington Post in which he said that Nabil’s sentencing proved “every word Nabil has ever said about our regime.”

“The military council wants to annihilate anyone who questions what it does,” wrote the blogger, who calls himself Kefaya Punk. “That reminds me of how the Catholic church treated its opponents in the medieval ages.”