Rolling Stone: In a major story in Sunday’s New York Times, national security reporter Mark Mazzetti details the troubling origins of the CIA’s targeted killing program in Pakistan – which he says began in 2004 with the killing of one of that country’s internal enemies, not a member of al Qaeda. The piece, which is adapted from Mazzetti’s new book, The Way of the Knife, also claims that the agency switched to killing accused terrorists – rather than capturing them – because of a 2004 internal review that was highly critical of the agency’s detention and interrogation program.

Targeted killing gave the CIA a way out of the prison business – but into the assassination business – and, as Mazzetti tells it, also a way to get access to Pakistani skies by taking out one of their enemies. Nek Muhammad was a tribal leader who had led a rebellion against Pakistan’s army and had been declared an “enemy of the state.” Pakistan wanted him dead. The CIA wanted access to airspace to conduct drone strikes in Pakistan’s tribal regions, which that country had previously considered a breach of sovereignty. The two countries made a deal – a high-stakes game of “you scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours” – that resulted in the CIA killing Nek Muhammad with a Predator drone, and Pakistan opening up part of its skies for CIA use. Pakistan’s military claimed responsibility for the killing, which Mazzetti notes was a lie, and to this day neither country has publicly given the real story.

The revelation that this first target was not part of al Qaeda, but rather a target picked by an ally country, has raised serious questions for critics of the CIA’s actions. “How many other killings have been carried out not pursuant to a strict legal analysis and examination of threat to the U.S., but rather as a bargaining chip, at the request of another government?” Sarah Knuckey, a lawyer and the director of NYU Law School’s Project on Extrajudicial Executions, asks Rolling Stone.

The secrecy in which the targeted killing program is shrouded makes that question impossible to answer conclusively at this time, but there is reason to believe that some of the individuals on the kill list (or lists) are known as “side payment” targets – people who are enemies of a U.S. ally, not the U.S. itself. Blogger Marcy Wheeler has argued that Nek Muhammad’s case “is surely” such a side-payment strike. [Continue reading…]

Category Archives: remote warfare

Drone war causing suffering on unprecedented scale in northwest Pakistan

AFP reports: After nine friends and relatives were killed in a US drone strike four years ago, Mohammed Fahim took tranquillisers to blot out the nightmares.

The 19 year-old is one of a growing number of Pakistanis living in the tribal areas on the Afghan border who has suffered from conditions related to depression, anxiety and mental health problems because of war.

US drone strikes, fighting between Pakistani Taliban and the army, mass displacement, chronic unemployment and disillusionment are all causing mental suffering on an unprecedented scale in northwest Pakistan, say psychiatrists.

Mohammed lost an eye in the January 2009 attack, but the mental scarring has been even more traumatic. The flashbacks are still sudden and powerful.

“I feel like my head is exploding,” he says when he remembers how four uncles, a cousin and four neighbours died when they came round for tea in North Waziristan, the most notorious of Pakistan’s Taliban and Al-Qaeda bastions.

“We heard the sound of a missile. A fraction of a second later, they were all dead, their bodies mutilated,” says Mohammed, who happened to be in the other room when the missile struck.

He insists that no one in his family was associated with Islamist militancy. US officials say the covert drone war in Pakistan involves surgical, pin-pointed strikes against known killers that cause few if any civilian casualties.

How the fear of war crimes charges led the CIA to abandon torture and take up murder

Mark Mazzetti writes: Nek Muhammad knew he was being followed.

On a hot day in June 2004, the Pashtun tribesman was lounging inside a mud compound in South Waziristan, speaking by satellite phone to one of the many reporters who regularly interviewed him on how he had fought and humbled Pakistan’s army in the country’s western mountains. He asked one of his followers about the strange, metallic bird hovering above him.

Less than 24 hours later, a missile tore through the compound, severing Mr. Muhammad’s left leg and killing him and several others, including two boys, ages 10 and 16. A Pakistani military spokesman was quick to claim responsibility for the attack, saying that Pakistani forces had fired at the compound.

That was a lie.

Mr. Muhammad and his followers had been killed by the C.I.A., the first time it had deployed a Predator drone in Pakistan to carry out a “targeted killing.” The target was not a top operative of Al Qaeda, but a Pakistani ally of the Taliban who led a tribal rebellion and was marked by Pakistan as an enemy of the state. In a secret deal, the C.I.A. had agreed to kill him in exchange for access to airspace it had long sought so it could use drones to hunt down its own enemies.

That back-room bargain, described in detail for the first time in interviews with more than a dozen officials in Pakistan and the United States, is critical to understanding the origins of a covert drone war that began under the Bush administration, was embraced and expanded by President Obama, and is now the subject of fierce debate. The deal, a month after a blistering internal report about abuses in the C.I.A.’s network of secret prisons, paved the way for the C.I.A. to change its focus from capturing terrorists to killing them, and helped transform an agency that began as a cold war espionage service into a paramilitary organization.

The C.I.A. has since conducted hundreds of drone strikes in Pakistan that have killed thousands of people, Pakistanis and Arabs, militants and civilians alike. While it was not the first country where the United States used drones, it became the laboratory for the targeted killing operations that have come to define a new American way of fighting, blurring the line between soldiers and spies and short-circuiting the normal mechanisms by which the United States as a nation goes to war.

Neither American nor Pakistani officials have ever publicly acknowledged what really happened to Mr. Muhammad — details of the strike that killed him, along with those of other secret strikes, are still hidden in classified government databases. But in recent months, calls for transparency from members of Congress and critics on both the right and left have put pressure on Mr. Obama and his new C.I.A. director, John O. Brennan, to offer a fuller explanation of the goals and operation of the drone program, and of the agency’s role.

Mr. Brennan, who began his career at the C.I.A. and over the past four years oversaw an escalation of drone strikes from his office at the White House, has signaled that he hopes to return the agency to its traditional role of intelligence collection and analysis. But with a generation of C.I.A. officers now fully engaged in a new mission, it is an effort that could take years.

Today, even some of the people who were present at the creation of the drone program think the agency should have long given up targeted killings. [Continue reading…]

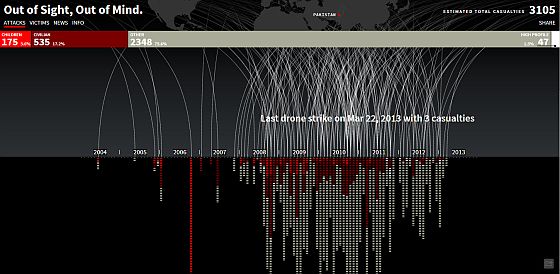

Drone war: Out of sight, out of mind

Click on the image above to view the “Out of Sight, Out of Mind” interactive graphic on the drone war in which an estimated 3,105 people have been killed in Pakistan of whom only 47 were so-called “high value” suspected terrorists.

A note on the producer of this interactive graphic: It comes from Pitch Interactive, an information visualization studio based in Berkeley, California. Their clients range from AT&T to Google to Fortune Magazine.

“The primary data used in this visualization comes from a dataset maintained by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism (BIJ)” — which is good because BIJ has compiled more information than anyone else has on the results of America’s drone war.

“This project helps to bring light on the topic of drones. Not to speak for or against, but to inform and to allow you to see for yourself whether you can support drone usage or not.”

Wes Grubbs, the studio’s founder, tweets: “We made this because it had to be made”.

McChrystal: America’s drone war risks provoking another attack on New York City

Retired General Stanley McChrystal: Anywhere you have undergoverned or ungoverned areas, organizations like al Qaeda have a tremendous opportunity to get a foothold. And when they can get a foothold, they can start to operate and spread from there.

Foreign Affairs: So what do you do with places like Mali and Yemen?

Well, you can’t solve all of them. You certainly don’t want to put Western forces in all of these countries. The initial reaction that says, “We will simply operate by drone strikes” is also problematic, because the inhabitants of that area and the world have significant problems watching Western forces, particularly Americans, conduct drone strikes inside the terrain of another country. So that’s got to be done very carefully, on occasion. It’s not a strategy in itself; it’s a short-term tactic.

It seems like the methods you pioneered in Iraq have been embraced by the U.S. government and the American public as a general approach to managing small-scale irregular warfare, and doing so in a way short of putting lots of boots on the ground or walking away entirely. Some would argue that this is the true legacy of Stan McChrystal — the creation of an approach to counterterrorism that is halfway between war and peace, at such a low cost and with such a light footprint that it’s politically viable for the long term in a way that war and disengagement are not. Do you disagree?

I question its universal validity. If you go back to the British tactics on the North-West Frontier, the “butcher and bolt” tactics, where they would burn an area and punish the people and say, “Don’t do that anymore,” and simultaneously offer a stipend to the leader while saying, “If you will remain friendly for a period of time, we’ll pay you” — that approach worked for a fair amount of time. It managed problems on their periphery. But it certainly didn’t solve the problems.

The tactics that we developed do work, but they don’t produce decisive effects absent other, complementary activities. We did an awful lot of capturing and killing in Iraq for several years before it started to have a real effect, and that came only when we were partnered with an effective counterinsurgency approach. Just the strike part of it can never do more than keep an enemy at bay. And although to the United States, a drone strike seems to have very little risk and very little pain, at the receiving end, it feels like war.

Americans have got to understand that. If we were to use our technological capabilities carelessly — I don’t think we do, but there’s always the danger that you will — then we should not be upset when someone responds with their equivalent, which is a suicide bomb in Central Park, because that’s what they can respond with.

Most Americans think ‘innocent until proven guilty’ only applies to Americans

Gallup poll: Nearly two-thirds of Americans (65%) think the U.S. government should use drones to launch airstrikes in other countries against suspected terrorists. Americans are, however, much less likely to say the U.S. should use drones to launch airstrikes in other countries against U.S. citizens living abroad who are suspected terrorists (41%); to launch airstrikes in the U.S. against suspected terrorists living here (25%); and to launch airstrikes in the U.S. against U.S. citizens living here who are suspected terrorists (13%).

Obama’s expanding empire of drone bases advances across Africa

The Washington Post reports: The newest outpost in the U.S. government’s empire of drone bases sits behind a razor-wire-topped wall outside this West African capital, blasted by 110-degree heat and the occasional sandstorm blowing from the Sahara.

The U.S. Air Force began flying a handful of unarmed Predator drones from here last month. The gray, mosquito-shaped aircraft emerge sporadically from a borrowed hangar and soar north in search of al-Qaeda fighters and guerrillas from other groups hiding in the region’s untamed deserts and hills.

The harsh terrain of North and West Africa is rapidly emerging as yet another front in the United States’ long-running war against terrorist networks, a conflict that has fueled a revolution in drone warfare.

Since taking office in 2009, President Obama has relied heavily on drones for operations, both declared and covert, in Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan, Yemen, Libya and Somalia. U.S. drones also fly from allied bases in Turkey, Italy, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates and the Philippines.

Now, they are becoming a fixture in Africa. The U.S. military has built a major drone hub in Djibouti, on the Horn of Africa, and flies unarmed Reaper drones from Ethiopia. Until recently, it conducted reconnaissance flights over East Africa from the island nation of the Seychelles. [Continue reading…]

CIA poised to hand over drone operations to Pentagon

Daily Beast: At a time when controversy over the Obama administration’s drone program seems to be cresting, the CIA is close to taking a major step toward getting out of the targeted killing business. Three senior U.S. officials tell The Daily Beast that the White House is poised to sign off on a plan to shift the CIA’s lethal targeting program to the Defense Department.

The move could potentially toughen the criteria for drone strikes, strengthen the program’s accountability, and increase transparency. Currently, the government maintains parallel drone programs, one housed in the CIA and the other run by DOD. The proposed plan would unify the command and control structure of targeted killings, and create a uniform set of rules and procedures. The CIA would maintain a role, but the military would have operational control over targeting. Lethal missions would take place under Title 10 of the U.S. Code, which governs military operations, rather than Title 50, which sets out the legal authorities for intelligence activities and covert operations. “This is a big deal,” says one senior administration official who has been briefed on the plan. “It would be a pretty strong statement.”

Officials anticipate a phased-in transition in which the CIA’s drone operations would be gradually shifted over to the military, a process that could take as little as a year. Others say it might take longer but would occur during President Obama’s second term. “You can’t just flip a switch, but it’s on a reasonably fast track,” says one U.S. official. During that time, CIA and DOD operators would begin to work more closely together to ensure a smooth hand-off. The CIA would remain involved in lethal targeting, at least on the intelligence side, but would not actually control the unmanned aerial vehicles. Officials told The Daily Beast that a potential downside of the Agency relinquishing control of the program was the loss of a decade of expertise that the CIA has developed since it has been prosecuting its war in Pakistan and beyond. At least for a period of transition, CIA operators would likely work alongside their military counterparts to target suspected terrorists. [Continue reading…]

America is asking all the wrong questions about drones

Jack L. Amoureux writes: Whether or not drones should be employed in the United States is the wrong question. Americans should be asking, “Is it ethical to use drones anywhere?”

Recently, concerns about how the U.S. government manages and deploys its fleet of around 7,000 drones have become especially prominent. Just last year President Obama, under mounting pressure, acknowledged the systematic use of drones in Iraq, Afghanistan, and elsewhere after a U.S. citizen was killed by a drone strike in Yemen.

Senate hearings on whether to confirm a key architect of the drone program, John Brennan, as director of the CIA underscore the increasingly urgent questions being asked of the administration. As part of the confirmation process, several senators insisted that the president share secret memoranda about drones, and Senator Rand Paul, R-Ky., mounted a 13-hour filibuster on the Senate floor over the administration’s refusal to rule out the possibility of a drone strike against a U.S. citizen on domestic soil.

But drones have become a hot button issue for a surprisingly diverse set of political actors only as armed drones flying over our heads have become more of a reality. Opposition has coalesced around the constitutional rights of U.S. citizens and a call for greater transparency and regulation of domestic drones. There is, however, a worrisome void in this debate about U.S. drone policy and practice — the lack of focus on the ethics of drones, whether used domestically or abroad. This neglect puts the United States out of step with the debates that are happening in the areas of the world most affected by drones. [Continue reading…]

The drone question Obama hasn’t answered

Ryan Goodman writes: The Senate confirmed John O. Brennan as director of the Central Intelligence Agency on Thursday after a nearly 13-hour filibuster by the libertarian senator Rand Paul, who before the vote received a somewhat odd letter from the attorney general.

“It has come to my attention that you have now asked an additional question: ‘Does the President have the authority to use a weaponized drone to kill an American not engaged in combat on American soil?’ ” the attorney general, Eric H. Holder Jr., wrote to Mr. Paul. “The answer to that question is no.”

The senator, whose filibuster had become a social-media sensation, elating Tea Party members, human-rights groups and pacifists alike, said he was “quite happy with the answer.” But Mr. Holder’s letter raises more questions than it answers — and, indeed, more important and more serious questions than the senator posed.

What, exactly, does the Obama administration mean by “engaged in combat”? The extraordinary secrecy of this White House makes the answer difficult to know. We have some clues, and they are troubling.

If you put together the pieces of publicly available information, it seems that the Obama administration, like the Bush administration before it, has acted with an overly broad definition of what it means to be engaged in combat. [Continue reading…]

The missing history of America’s third war

Micah Zenko writes: Since 11:47 on Wednesday morning, the beginning of a Senate filibuster to delay a vote on John Brennan’s nomination to head the CIA, “Rand Paul,” “drones,” and “John Brennan” have intermittently been trending on Twitter. This attention-grabbing focus on targeted killings — which will last only until Paul runs out of steam — is representative of the sporadic attention that the controversial tactic has received from policymakers and the public.

With each supposed revelation — the “kill list,” “signature strikes,” “disposition matrix,” and the leaking of a Department of Justice white paper providing the legal justification for killing American citizens — there is a frenzy of interest in drone strikes. Analysts (myself included) are repeatedly asked, “Where is this all heading in five or ten years?” In other words: What additional lethal missions will U.S. armed drones execute, and where will they occur? What other states will seek to develop this military capability?

But, in general, there is relative indifference to the history of America’s Third War — the 10-year campaign of over 400 targeted killings in non-battlefield settings that have killed an estimated 3,500 to 4,700 people. And that is puzzling, particularly since they have become a defining feature of post-9/11 U.S. foreign policy.

Over the past few months, many stakeholders in and out of government have offered recommendations about how the Obama administration should change, limit, end, or enhance its targeted killing policies. However, there have been no calls for an official government study into the history and evolution of non-battlefield targeted killings. This is essential, since reforms must first be informed by an accurate accounting of how the policies were originally conceived, how they were implemented and altered based on updated information, whether they succeeded or failed at achieving their objectives, and what their intended and unintended effects have been. [Continue reading…]

Barack Obama ‘has authority to use drone strikes to kill Americans on U.S. soil’

The Telegraph reports: President Barack Obama has the authority to use an unmanned drone strike to kill US citizens on American soil, his attorney general has said.

Eric Holder argued that using lethal military force against an American in his home country would be legal and justified in an “extraordinary circumstance” comparable to the September 11 terrorist attacks.

“The president could conceivably have no choice but to authorise the military to use such force if necessary to protect the homeland,” Mr Holder said.

His statement was described as “more than frightening” by Senator Rand Paul, a Republican from Kentucky, who had demanded to know the Obama administration’s position on the subject.

The way the U.S. is teaching the world to use drones

Paul J. Saunders considers the lessons that states around the world must currently be drawing from Washington’s approach to the use of drones.

Thus far, the principal lesson may well be that drones can be extremely effective in killing your opponents, wherever they are, without risking your own troops and without sending soldiers or law enforcement personnel across another country’s borders. It seems less likely that others will adopt U.S.-style legal standards and oversight procedures, or that they will always ask other governments before sending drones into their airspace.

Based on their actions, it is almost as if Obama administration officials believe that the United States and its allies will have a long-term monopoly on drones. How else can one explain their exuberant confidence in launching drone attacks? However, the administration’s dramatic expansion in drone strikes — and their apparent effectiveness — will only further shorten Washington’s reign as the drone capital of the world by increasing the incentives to others eager to develop, refine or buy the technology.

Have Obama administration officials given any thought to what the world might look like when armed drones are more widespread and when Americans or U.S. allies and partners could become targets? To an outsider, there is little evidence of this kind of thinking in the administration’s use of drones.

This is a serious problem. According to an unclassified July 2012 report by the Government Accountability Office, at least 76 countries already have acquired unmanned aerial vehicles, known as UAVs or drones; the report also states that “countries of concern” are attempting to acquire advanced UAVs from foreign suppliers as well as seeking illegal access to U.S. technology. And a 2012 special report by the United Kingdom’s Guardian newspaper indicated that China has 10 or more models, though not all are armed. Other sources identify additional varieties in China. At least 50 countries are trying to build 900 different types of drones, the GAO writes.

More generally, the administration’s expanding use of drones is a powerful endorsement of not only the technology, but of the practice of targeted killing as an instrument of foreign and security policy. Having provided this powerful impetus, the United States should not be surprised if others — with differing legal standards and more creative efforts at self-justification — seize upon it once they have the necessary capabilities. According to the GAO, this is already happening — in government-speak, “while only a limited number of countries have fielded lethal or weaponized UAVs, this threat is anticipated to grow.” From this perspective, it is ironic that a president so critical of his predecessor’s unilateralism would practice it himself—particularly in a manner that other governments will find much easier to emulate than the Bush administration’s larger-scale use of force.

British nationals stripped of citizenship then killed by U.S. drones

The Bureau of Investigative Journalism: The [British] government has secretly ramped up a controversial programme that strips people of their British citizenship on national security grounds – two of whom have been subsequently killed by US drone attacks.

An investigation by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism and published in The Independent has established that since 2010 the Home Secretary Theresa May has revoked the passports of 16 individuals many of whom are alleged to have had links to militant or terrorist groups.

Critics of the programme warn that it also allows ministers to ‘wash their hands’ of British nationals suspected of terrorism who could be subject to torture and illegal detention abroad.

They add that it also allows those stripped of their citizenship to be killed or ‘rendered’ without any onus on the British government to intervene.

At least five of those deprived of their UK nationality by the Coalition government were born in Britain, and one man had lived in the country for almost 50 years.

Those affected have their passports cancelled, and lose their right to enter the UK – making it very difficult to appeal the Home Secretary’s decision.

Last night the Liberal Democrat’s deputy leader Simon Hughes said he was writing to the Home Secretary to call for an urgent review into how the law was being implemented.

The leading human rights lawyer Gareth Peirce said the present situation ‘smacked of medieval exile, just as cruel and just as arbitrary’.

Ian Macdonald QC, president of the Immigration Law Practitioners’ Association, described the citizenship orders as ‘sinister’.

‘They’re using executive powers and I think they’re using them quite wrongly,’ he said.

‘It’s not open government, it’s closed, and it needs to be exposed because in my view it’s a real overriding of open government and the rule of law.’ [Continue reading…]

Video: U.S. media complicity in concealing drone war

Why the Pentagon hates Obama’s drone war

Micah Zenko writes: General Stanley McChrystal is speaking out against the Obama administration’s use of drone strikes, echoing previous warnings and clashing with the White House’s carefully cultivated narrative:

To the Daily Telegraph:

It’s very tempting for any country to have a clean, antiseptic approach, that you can use technology, but it’s not something that I think is going to be an effective strategy, unless it is part of a wider commitment.

To Reuters:

They are hated on a visceral level, even by people who’ve never seen one or seen the effects of one.

To journalist Trudy Rubin:

[Drones are] a very limited approach that gives the illusion you are making progress because you are doing something.

And to television anchor Candy Crowley:

It can lower the threshold for decision making to take action that at the receiving end, feels very different at the receiving end.

McChrystal offers a unique perspective on the debate surrounding drone strikes. Serving as the commander of Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC) from 2003 to 2008, he restructured the secretive unit to capture or kill hundreds of suspected militants and terrorists in Iraq, Afghanistan, and elsewhere. During this time, he had the authority to deploy U.S. forces into Pakistan — without prior approval from the White House — in order to capture or kill Osama bin Laden. As commander of the international and U.S. forces in Afghanistan from June 2009 to July 2010, he significantly tightened the rules of engagement for airstrikes in populated areas, noting, “Air power contains the seeds of our own destruction.” (Full disclosure: McChrystal served on the advisory committee of my recent report on U.S. drone strikes, although that does not mean he agreed with my findings or recommendations.)

Although his candor is rare in his field, many of McChrystal’s concerns are increasingly shared by active-duty and retired military officials with whom I’ve spoken. The vast majority of these officers, who held a wide range of positions while in uniform, are deeply troubled by the Obama administration’s ongoing drone wars for five reasons. [Continue reading…]

So-called due process for so-called Americans

Amy Davidson writes: “One of the problems is, once the drone program is so public, and one American is caught up, people don’t know much about this one ‘American citizen’ — so called,” said Senator Dianne Feinstein, in her questioning of John Brennan, President Obama’s nominee for C.I.A. director, on Thursday. (John Cassidy has more on the hearing.) She was referring to Anwar al-Awlaki, who was killed by a drone strike in Yemen, in 2011, and was a “so-called” American because he was an American, born in New Mexico. “They don’t know what he’s been doing,” Feinstein continued. “They don’t know the incitement he has stirred up. I wonder if you could tell us a little bit about Mr. Awlaki and what he’s been doing.”

Brennan demurred at first, since the question was about an “operation.” Feinstein jumped in:

See, that’s the problem. When people hear “American,” they think someone who’s upstanding. And this man was not upstanding by a long shot.

BRENNAN: Yes.

FEINSTEIN: And maybe you cannot discuss it here, but I’ve read enough to know that he was a real problem.

Brennan agreed, saying that al-Awlaki “was intimately involved in activities that were designed to kill innocent men, women, and children, mostly Americans. He was not just a propagandist.” (He neglected to mention that al-Awlaki’s American teen-age son was also killed, in a separate strike.) Feinstein then led him through a number of incidents; in some cases, Brennan agreed that al-Awlaki was an organizer, and in others he spoke obliquely about “inspiring” and “inciting individuals.” Feinstein summed up the exchange with what may have been the most disturbing line in the three-hour hearing, worse, even, than the waterboarding joke that Senator Burr told a few minutes later:

“And, so, Mr. Awlaki is not an American citizen by where anyone in America would be proud.”

“Proud,” “upstanding,” “so-called American” — is this the basis on which the Senate is judging fundamental questions of American rights and due process?

It’s natural and appropriate the Americans should be concerned that the U.S. president has decided that he can at his discretion deprive U.S. citizens of their right to due process, but in considering the assassination of Anwar al Awlaki, we should not be alarmed merely because he was an American. Much more significant, it seems to me, is why he was killed.

At the time of his death, U.S. officials described Awlaki as an operational leader of al Qaeda, yet have never supported this claim with any evidence. Lack of evidence presumably explains why he was never indicted and never placed on the FBI’s Most Wanted list.

What Awlaki was guilty of was being a charismatic preacher, capable of exerting great influence and quite possibly inspiring others to engage in acts of terrorism. In 2010, the Wall Street Journal reported:

A businessman in [Yemen’s capital,] San’a said he met the cleric two years ago, while Mr. Awlaki was hunting for real estate in the capital. The businessman said he was immediately struck by the charisma of the cleric. “It was like talking to [Bill] Clinton,” he said. “You felt like he understood everything about you.”

Awlaki represented a national security nightmare: a Bin Laden with an American accent. He was feared much less for what he had done than for what he might become.

The idea that he was killed because he posed some kind of imminent threat is an idea that can only be accepted on blind faith. What the preponderance of evidence shows is that this was a political assassination.

When the U.S. government starts executing people for political crimes, the nationality of those being killed should really be the least among our concerns.

Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the alleged architect of the 9/11 attacks was arrested rather than being summarily executed. No doubt at the time he was regarded as being much more valuable alive than dead. The same can’t be said of Awlaki. Indeed, the difficulties the Obama administration might have faced imprisoning him and attempting to put him on trial, strongly suggest that he was killed as a matter of convenience. He was a problem that needed to be removed — snuffed out — and the choice to do that, turned the position of the president into that of a mobster.

How we made killing easy

David Cole writes: On Monday, NBC published a leaked Justice Department “white paper” laying out the Obama administration’s case for when the president, or indeed any “informed, high-level official” of the federal government, can authorize the secret killing of a US citizen without charges, a hearing, or a trial. The paper, which appears to summarize a still-classified internal memorandum drafted by the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel to authorize the targeted killing in September 2011 of US citizen Anwar al-Awlaki, provides more detail than has yet been made public about the administration’s controversial drone program.

Consistent with the positions taken in public speeches by former State Department Legal Advisor Harold Koh, Attorney General Eric Holder, and White House counterterrorism advisor and CIA director-nominee John Brennan, the sixteen-page white paper argues that killing a US citizen with a drone and without trial is legal under domestic and international law, even if the individual is far from any battlefield, not a member of al-Qaeda, and not engaged in planning an imminent attack on the United States. To date, much of the concern about the administration’s drone program has stemmed from its largely secret character; unfortunately, the more we learn, the greater those concerns become.

It is unclear why this document had to be leaked in order to enter the public domain. It is not marked classified, and appears to be designed for public consumption — why else would a separate white paper need to be drawn up to describe legal reasoning already contained in a classified OLC memorandum? It may well have been drafted to see whether the contours of the OLC memorandum could be made public without disclosing any classified or sensitive information. But if that’s the case, why didn’t the Obama administration release the paper as an official public act? In opposing a Freedom of Information Act suit filed by the ACLU, the administration is fighting tooth and nail to keep everything about the drone program secret, but this paper suggests that much more could be disclosed — for example, the procedures and standards employed for placing someone on the “kill list,” and the general bases for and results of actual strikes — without the sky falling. If this administration is truly committed to transparency, memos like this should not have to be obtained by the media through back channels.

The white paper addresses the legality of killing a US citizen “who is a senior operational leader of al-Qaeda or an associated force.” Such a person may be killed, the document concludes, if an “informed, high-level official” finds (1) that he poses “an imminent threat of violent attack against the United States;” (2) that his capture is not feasible; and (3) the operation is conducted consistent with law-of-war principles, such as the need to minimize collateral damage. However, the paper offers no guidance as to what level of proof is necessary: does the official have to be satisfied beyond a reasonable doubt, by a preponderance of the evidence, or is reasonable suspicion sufficient? We are not told.

Nor does the paper describe what procedural safeguards are to be employed. It only tells us what is not required: having a court determine whether the criteria are in fact met. The paper asserts that this assessment is best left entirely to the executive because it involves foreign affairs and military tactics, and maintains that judicial review would impermissibly require a court to “supervise inherently predictive judgments by the President and his national security advisors.” But courts review executive predictive judgments every time they rule on a government request for a search or wiretap warrant, including those sought for national security purposes under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act. If courts routinely issue warrants for arrests and searches, why are they somehow unable to issue warrants for drone strikes?

From news reports, we know that the targeted killing program involves elaborate preparation and review of “kill lists,” debated in weekly conference calls in which as many as one hundred people take part. The US citizen and radical Islamist Anwar al-Awlaki was reportedly on such a list for more than a year before he was killed. With that kind of time frame, there is no logistical reason why independent judicial review could not have taken place. [Continue reading…]