Luay al-Khatteeb writes: Once again, the subject of illicit financial flows from kleptocratic regimes is in the international spotlight, this time in the form of the “Panama Papers.”

What is surprising is the level of shock at something that should have been obvious. For a long time, many financial institutions turned a blind eye to nefarious PEPs (politically exposed persons) and not just in Switzerland, as we see now with big names such as HSBC, once again deflecting allegations.

The industrialized world can’t afford any more surprises like this, otherwise aid and loans will continue to enter weak states, only to be rapidly snuck out.

Encouragingly, there are signs that governments and regulators are being energized by the Panama Papers. The U.S. Treasury will soon announce a requirement that banks disclose the owners of shell companies, and in the UK regulators set a deadline for banks to disclose details of clients’ relations with Mossack Fonseca, the company at the centre of the current storm.

Iraq, with lamentably high corruption, can be a litmus test for revived effort. Iraq also desperately needs to recover stolen assets, because it is running out of money for both fighting ISIS and rebuilding Iraq, in order to prevent ISIS 2.0.

Luckily, the United States is leading the way with the formation of the Kleptocracy Asset Recovery Initiative (KARI), but far more global coordination is needed. In Iraq, financial assistance should be put into ministries to train people in spotting and preventing corruption.

There are certainly good young people who want change in the Iraqi government, the challenge is creating a culture where they can speak out. That will take a renewed and internationally coordinated capacity building effort. As an example, the Higher Council of Education Development, an Iraqi organization that has sent four thousand students overseas to help ministerial capacity, had a budget of just over $100 million last year. The international community must urgently help Iraq to resource such work, because so far war expenditures dwarf other efforts. [Continue reading…]

Category Archives: Iraq

Iraq’s Shi’ite rivalries risk turning violent, weakening war on ISIS

Reuters reports: A power struggle within Iraq’s Shi’ite Muslim majority has intensified as attempts to form a new government flounder, threatening to turn violent and ruin U.S.-led efforts to defeat Islamic State.

For the first time since the U.S. withdrawal at the end of 2011, Shi’ite factions came close to taking arms against each another last month, when followers of powerful cleric Moqtada al-Sadr stormed the parliament in Baghdad’s Green Zone.

Rival Shi’ite militiamen took up positions nearby, raising the specter of intra-Shi’ite fighting similar to events in the southern city of Basra in 2008, in which hundreds of people were killed.

Trucks carrying those militiamen, armed with rocket-propelled grenades and machine guns, patrolled the capital in clear view of the security forces, video published on the website of Iranian-backed group Saraya al-Khorasani showed.

The crisis presents the biggest political challenge yet to Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi, a moderate Shi’ite Islamist who took office in 2014 promising to defeat Islamic State, mend rifts with the minority Sunnis and Kurds, and root out corruption eating away at state income which has already been eroded by a slump in oil prices.

Sadr, the heir of a revered clerical dynasty, says he backs Abadi’s planned political reforms and has accused other Shi’ite leaders of seeking to preserve a system of political patronage that makes the public administration rife for corruption.

His followers stormed the heavily fortified Green Zone on April 30 after rival political groups blocked parliamentary approval of a new cabinet made up of independent technocrats proposed by Abadi to fight graft.

A commander in Saraya al-Khorasani, which deployed near the Green Zone in response, made it clear that they would fight rather than allow Sadr’s followers to occupy the district which houses parliament, government offices and embassies.

“We are here to kill this sedition in its cradle,” the commander, dressed in green camouflage and a black turban told his fighters, the online video shows. [Continue reading…]

Fallujah could be the next big battle of the ISIS war

The Daily Beast reports: The Iraqi government is putting the ISIS-controlled city of Fallujah as next on its target list.

That’s not because of increasingly dire reports that the citizens of Fallujah are suffering from starvation and torture under ISIS’s cruel grip. Nor do Iraqi officials see the city as key to dislodging ISIS from its Iraqi stronghold, Mosul.

Rather, Iraqi officials have told their American counterparts that they suspect the restive Sunni-dominated city is sending jihadists to attack Baghdad, the Shiite-dominated capital. In the last week, there have been multiple daily bombings in Baghdad that have killed more than 200 people and wounded hundreds more. On Tuesday alone, a combination of suicide attacks and car bombings took the lives of nearly 70 people; ISIS claimed responsibility for some of those bombings.

In other words: While all eyes were on Baghdad and the deadliest spate of bombings to strike the capital in years, the Iraqi government was quietly pointing its finger at Fallujah.

Such accusations toward Fallujah, arguably, is precisely what ISIS wanted its bombings to incite, a return to the kind of sectarianism that has, in the past, threatened to tear the state apart — and was supposed to dissipate under Prime Minister Haider al Abadi. [Continue reading…]

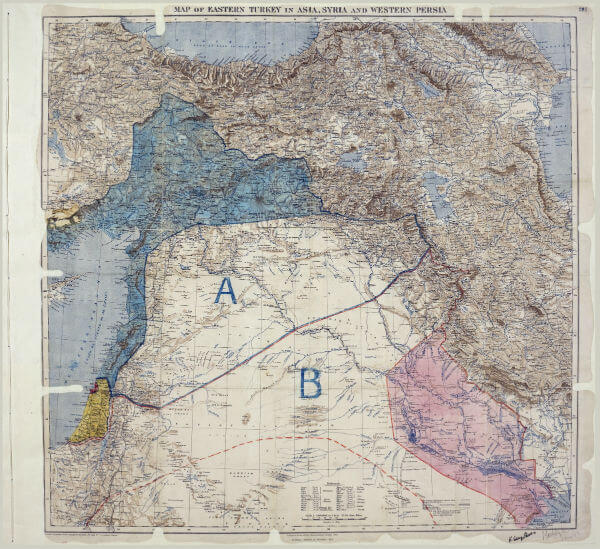

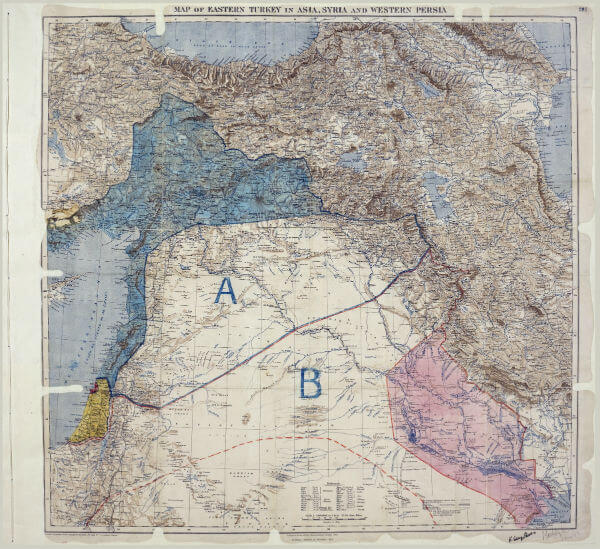

The map ISIS hates

In 2014, Malise Ruthven wrote: When the jihadists of ISIS (the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria) tweeted pictures of a bulldozer crashing through the earthen barrier that forms part of the frontier between Syria and Iraq, they announced — triumphantly — that they were destroying the “Sykes-Picot” border. The reference to a 1916 Franco-British agreement about the Middle East may seem puzzling, coming from a radical group fighting a brutal ethnic and religious insurgency against Bashar al-Assad’s Syria and Nouri al-Maliki’s Iraq. But jihadist groups have long drawn on a fertile historical imagination, and old grievances about the West in particular.

This symbolic action by ISIS fighters against a century-old imperial carve-up shows the extent to which one of the most radical groups fighting in the Middle East today is nurtured by the myth of precolonial innocence, when the Ottoman Empire and Sunni Islam ruled over an unbroken realm from North Africa to the Persian Gulf and the Shias knew their place. (Indeed, the Arabic name of ISIS — al-Dawla al-Islamiya fil-Iraq wa al-Sham — refers to a historic idea of the greater Levant (al-Sham) that transcends the region’s modern, Western-imposed state borders.)

But why is Sykes-Picot so important? One reason is that it stands near the beginning of what many Arabs view as a sequence of Western betrayals spanning from the dismantling of the Ottoman Empire in World War I to the establishment of Israel in 1948 and the 2003 invasion of Iraq. The Sykes-Picot agreement — named after the British and French diplomats who signed it — was entered in secret, with Russia’s assent, in May 1916 to divide the Arab provinces of the Ottoman Empire into British and French “spheres of influence.” It designated each power’s areas of future control in the event of victory by the Triple Entente over Germany, Austria, and their Ottoman ally. Under the agreement Britain was allocated the coastal strip between the Mediterranean and the river Jordan, Transjordan and southern Iraq, with enclaves including the ports of Haifa and Acre, while France was allocated south-eastern Turkey, northern Iraq, all of Syria and Lebanon. Russia was to get Istanbul, the Dardanelles, and the Ottoman Empire’s Armenian districts.

Under the 1920 San Remo agreement, which built on Sykes-Picot, the Western powers were free to decide on state boundaries within these areas. The international frontiers — with Iraq’s framed by the merging of the three Ottoman vilayets of Mosul, Baghdad, and Basra — were consolidated by the separate mandates granted by the League of Nations to France in Lebanon and Syria, and to Britain in Palestine, Transjordan, and Iraq. The frontier between French-controlled Syria and British-controlled Iraq included the desert of Anbar province that was bulldozed by ISIS this month.

Kept hidden for more than a year, the Anglo-French pact caused a furor when it was first revealed by the Bolsheviks after the 1917 Russian Revolution — with the Syrian Congress, convened in July 1919, demanding “the full freedom and independence that had been promised to us.” Not only did the agreement map out — unbeknownst to the Arab leaders of the time — a new system of Western control of local populations. It also directly contradicted the promise that Britain’s man in Cairo, Sir Henry McMahon, had made to the ruler of Mecca, the Sharif Hussein, that he would have an Arab kingdom in the event of Ottoman defeat. In fact, that promise itself, which had been conveyed in McMahon’s correspondence with the Sharif between July 1915 and January 1916, left ambiguous the borders of the future Arab state, and was later used to deny Arab control of Palestine. McMahon had excluded from the proposed Arab kingdom “portions of Syria lying to the west of the districts of Damascus, Homs, Hama and Aleppo [that] cannot be said to be purely Arab.” This clause led to lengthy and bitter debates as to whether Palestine — which Britain meanwhile promised as a homeland for Jews under the terms of the November 1917 Balfour Declaration — could be defined as lying “west” of the vilayet, or district, of Damascus. [Continue reading…]

Untangling the complicated legacies of colonialism and failed Arab regimes overshadowing today’s conflicts in the Middle East

Rami G Khouri writes: Why have most Middle Eastern lands that Great Britain, Italy, and France managed as mandates or colonies become violent wrecks and sources of large-scale conflict and human despair? It is just as dishonest to blame mainly Western colonialism for our national wreckages and rampant instability as it is to blame only Arab people and culture for those failings. We need a more complete and integrated analysis of the multiple phenomena that shaped our last erratic century.

Initially, we must absolutely acknowledge that Arab states’ inability to achieve sustainable economic growth and pluralistic democracies is the core reason for our problems today. The main reason for this reason, however, is to be found in a more complex set of interlocking relationships among powerful political actors inside our countries and capitals far and near.

This requires going back before 1916, maybe a century or two, to recall how European powers conquered much of the world as colonies or sites of unchecked imperial plunder. The main problem with Sykes-Picot is not only what happened in and after 1916; it is also heavily a consequence of the European colonial mindset that matured in the century before 1916, and continued to exercise its colonial prerogatives for decades to follow — perhaps even in today’s continued use of European, Russian, and American military power across our region.

At the same time, three critical issues after 1916 made it virtually impossible for many Arab countries to transition from Euro-manufactured instant states born on after-dinner napkins in the hands of Cognac-mellowed British and French colonial officers, to stable, democratic, prosperous sovereign states.

These three issues were, in their historical order:

1) British support for Zionism and a Jewish state in Palestine in November 1917, which plunged Palestine into endless Zionism-Arabism warfare since then, and sucked in other Arab states, Iran, and others yet;

2) the discovery of large amounts of oil in the Middle East in the 1930s especially, which the West needed to maintain access to for its own industrial expansion; and,

3) the post-1947 Cold War between the U.S.-led West and the Russian-led Soviet Communist states that was translated into perpetual proxy wars across the Middle East for forty-four years, and maybe is resurfacing today in new guises. [Continue reading…]

Don’t blame Sykes-Picot for the Middle East’s mess

Steven A. Cook and Amr T. Leheta write: Sometime in the 100 years since the Sykes-Picot agreement was signed, invoking its “end” became a thing among commentators, journalists, and analysts of the Middle East. Responsibility for the cliché might belong to the Independent’s Patrick Cockburn, who in June 2013 wrote an essay in the London Review of Books arguing that the agreement, which was one of the first attempts to reorder the Middle East after the Ottoman Empire’s demise, was itself in the process of dying. Since then, the meme has spread far and wide: A quick Google search reveals more than 8,600 mentions of the phrase “the end of Sykes-Picot” over the last three years.

The failure of the Sykes-Picot agreement is now part of the received wisdom about the contemporary Middle East. And it is not hard to understand why. Four states in the Middle East are failing — Syria, Iraq, Yemen, and Libya. If there is a historic shift in the region, the logic goes, then clearly the diplomatic settlements that produced the boundaries of the Levant must be crumbling. History seems to have taken its revenge on Mark Sykes and his French counterpart, François Georges-Picot, who hammered out the agreement that bears their name.

The “end of Sykes-Picot” argument is almost always followed with an exposition of the artificial nature of the countries in the region. Their borders do not make sense, according to this argument, because there are people of different religions, sects, and ethnicities within them. The current fragmentation of the Middle East is thus the result of hatreds and conflicts — struggles that “date back millennia,” as U.S. President Barack Obama said — that Sykes and Picot unwittingly released by creating these unnatural states. The answer is new borders, which will resolve all the unnecessary damage the two diplomats wrought over the previous century.

Yet this focus on Sykes-Picot is a combination of bad history and shoddy social science. And it is setting up the United States, once again, for failure in the Middle East.

For starters, it is not possible to pronounce that the maelstrom of the present Middle East killed the Sykes-Picot agreement, because the deal itself was stillborn. Sykes and Picot never negotiated state borders per se, but rather zones of influence. And while the idea of these zones lived on in the postwar agreements, the framework the two diplomats hammered out never came into existence.

Unlike the French, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George’s government actively began to undermine the accord as soon as Sykes signed it — in pencil. The details are complicated, but as Margaret Macmillan makes clear in her illuminating book Paris 1919, the alliance between Britain and France in the fight against the Central Powers did little to temper their colonial competition. Once the Russians dropped out of the war after the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, the British prime minister came to believe that the French zone that Sykes and Picot had outlined — comprising southeastern Turkey, the western part of Syria, Lebanon, and Mosul — was no longer a necessary bulwark between British positions in the region and the Russians.

Nor are the Middle East’s modern borders completely without precedent. Yes, they are the work of European diplomats and colonial officers — but these boundaries were not whimsical lines drawn on a blank map. They were based, for the most part, on pre-existing political, social, and economic realities of the region, including Ottoman administrative divisions and practices. The actual source of the boundaries of the present Middle East can be traced to the San Remo conference, which produced the Treaty of Sèvres in August 1920. Although Turkish nationalists defeated this agreement, the conference set in motion a process in which the League of Nations established British mandates over Palestine and Iraq, in 1920, and a French mandate for Syria, in 1923. The borders of the region were finalized in 1926, when the vilayet of Mosul — which Arabs and Ottomans had long associated with al-Iraq al-Arabi (Arab Iraq), made up of the provinces of Baghdad and Basra — was attached to what was then called the Hashemite Kingdom of Iraq.

On a deeper level, critics of the Middle East’s present borders mistakenly assume that national borders have to be delineated naturally, along rivers and mountains, or around various identities in order to endure. It is a supposition that willfully ignores that most, if not all, of the world’s settled borders are contrived political arrangements, more often than not a result of negotiations between various powers and interests. Moreover, the populations inside these borders are not usually homogenous.

The same holds true for the Middle East, where borders were determined by balancing colonial interests against local resistance. These borders have become institutionalized in the last hundred years. In some cases — such as Egypt, Iran, or even Iraq — they have come to define lands that have long been home to largely coherent cultural identities in a way that makes sense for the modern age. Other, newer entities — Saudi Arabia and Jordan, for instance — have come into their own in the last century. While no one would have talked of a Jordanian identity centuries ago, a nation now exists, and its territorial integrity means a great deal to the Jordanian people.

The conflicts unfolding in the Middle East today, then, are not really about the legitimacy of borders or the validity of places called Syria, Iraq, or Libya. Instead, the origin of the struggles within these countries is over who has the right to rule them. The Syrian conflict, regardless of what it has evolved into today, began as an uprising by all manner of Syrians — men and women, young and old, Sunni, Shiite, Kurdish, and even Alawite — against an unfair and corrupt autocrat, just as Libyans, Egyptians, Tunisians, Yemenis, and Bahrainis did in 2010 and 2011.

The weaknesses and contradictions of authoritarian regimes are at the heart of the Middle East’s ongoing tribulations. Even the rampant ethnic and religious sectarianism is a result of this authoritarianism, which has come to define the Middle East’s state system far more than the Sykes-Picot agreement ever did. [Continue reading…]

Kurdish tensions undermine the war against ISIS

Hassan Hassan writes: Amnesty International has in seven months issued two major reports highlighting allegations of war crimes by rebel and Kurdish forces in northern Syria. The two reports are related to a secondary conflict brewing between Arabs and Kurds from Hasakah to Qamashli to Aleppo, which could easily spin out of control and add to the many conflicts that already plague the country.

The United States has an unintentional hand in this new conflict, and de-escalation hinges largely on whether Washington is willing to review its strategy in northern Syria, which sometimes privileges the appearance of success in the battle against ISIL over sustainable policies.

On Friday, Amnesty published a damning new report accusing rebel factions in Aleppo, organised under the Army of Conquest, of committing acts that may amount to war crimes. The rights group said it gathered strong evidence of indiscriminate attacks that killed at least 83 civilians, including 30 children, in the Kurdish-dominated Sheikh Maqsoud between February and April.

On October 13 last year, Amnesty issued a report, Forced Displacement and Demolitions in Northern Syria, accusing the Kurdish political party PYD, the Democratic Union Party, of carrying out a wave of forced displacement and home demolitions that it also said may amount to war crimes. The shelling of civilians by rebel forces cannot be justified, and perpetrators must be punished and restrained by their regional backers. The attacks on Sheikh Maqsoud were encouraged by some supporters of the opposition living abroad, after the PYD’s military wing, the YPG, attacked the rebels in February. Worse, such calls continue to be heard and more indiscriminate attacks can be expected. [Continue reading…]

Belgium to begin air strikes against ISIS in Syria

AFP reports: Belgium will extend its F-16 air strikes against Islamic State jihadists in Iraq into Syria, the government said Friday, as it grapples with the aftermath of deadly IS-claimed bomb attacks in Brussels in March.

“In accordance with UN Resolution 2249, the engagement will be limited to those areas of Syria under the control of IS and other terrorist groups,” a spokesman for Prime Minister Charles Michel told AFP after a cabinet meeting.

“The objective will be to destroy these groups’ refuges,” the spokesman said, adding that the strikes would begin on July 1.

Belgium launched its first attacks against IS in Iraq in late 2014 as part of the US-led coalition, but decided against strikes in Syria amid public fears over getting dragged into a wider conflict. [Continue reading…]

Behind the carnage in Iraq: ISIS intends to divide and conquer

The Daily Beast reports: Baghdad suffered its deadliest day in months during a series of attacks Wednesday. The carnage not only shocked the capital, but also raised questions about whether Iraqi security forces are capable of reclaiming Mosul, Iraq’s second-largest city, which has been occupied for almost two years by the self-proclaimed Islamic State.

One obvious question is how Iraqi security forces can retake and secure Mosul if they cannot protect Baghdad from three suicide bombings in a matter of hours. But the picture is more complicated, and indeed, more problematic even than that.

The bombings targeted Shia neighborhoods in what appears to be part of the continuing ISIS effort to provoke a frenzy of ethnic cleansing similar to that of a decade ago. As one U.S. official immersed in the anti-ISIS war puts it, “Sunnis see ISIS as their protection — their wall against Shia revenge.”

The estimates of those killed Wednesday are as high as 150, with hundreds more injured. Among those reportedly killed were several women at a hair salon struck by a truck bomb as they prepared for their wedding day. [Continue reading…]

Lack of plan for ISIS detainees raises human rights concerns

The New York Times reports: The Islamic State calls them “inghimasi” — zealous foot soldiers who intend to fight to their deaths. And as the American-backed coalition has reclaimed territory from the group in Iraq and Syria, that fervor has kept prisoners from being much of a problem: The shooting only stops when almost every Islamic State fighter has been killed.

But that could change as the coalition moves toward the Islamic State’s largest urban strongholds — Mosul, Iraq, and Raqqa, Syria — raising a potential problem for the United States. If the coalition is successful and thousands of ordinary members of a collapsing Islamic State have nowhere left to retreat, will they start to surrender in greater numbers? And if so, who will be responsible for imprisoning them?

After the experiences of the past decade in the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, the Obama administration is determined not to revive large-scale detention operations. But it is far from clear whether allies on the ground — especially rebels in Syria — are prepared to hold large numbers of prisoners, raising the prospect of an ugly aftermath to any victory.

“If they’re not killed but detained, we are concerned about the standards of care, who would do it and how it would be done,” Peter Maurer, the president of the International Committee of the Red Cross, said in an interview. [Continue reading…]

In remote corner of Iraq, an unlikely alliance forms against ISIS

Reuters reports: They share little more than an enemy and struggle to communicate on the battlefield, but together two relatively obscure groups have opened up a new front against Islamic State militants in a remote corner of Iraq.

The unlikely alliance between an offshoot of a leftist Kurdish organization and an Arab tribal militia in northern Iraq is a measure of the extent to which Islamic State has upended the regional order.

Across Iraq and Syria, new groups have emerged where old powers have waned, competing to claim fragments of territory from Islamic State and complicating the outlook when they win.

“Chaos sometimes produces unexpected things,” said the head of the Arab tribal force, Abdulkhaleq al-Jarba. “After Daesh (Islamic State), the political map of the region has changed. There is a new reality and we are part of it.”

In Nineveh province, this “new reality” was born in 2014 when official security forces failed to defend the Sinjar area against the Sunni Islamic State militants who purged its Yazidi population.

A Syrian affiliate of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) came to the rescue, which won the gratitude of Yazidis, and another local franchise called the Sinjar Resistance Units (YBS) was set up.

The mainly Kurdish secular group, which includes Yazidis, controls a pocket of territory in Sinjar and recently formed an alliance with a Sunni Arab militia drawn from the powerful Shammar tribe.

“In the beginning we were unsure (about them),” said a wiry older member of the Arab force, which was assembled over the past three months and is now more than 400-strong. “We thought they were Kurdish occupiers.”

Their cooperation is all the more unusual because many Yazidis accuse their Sunni Muslim neighbors of complicity in atrocities committed against them by Islamic State, and say they cannot live together again. [Continue reading…]

Mosul: Suspicion and hostility cloud fight to recapture Iraqi city from ISIS

The Guardian reports: At the bottom of a hill near the frontline with Islamic State fighters, the Iraqi army had been digging in. Their white tents stood near the brown earth gouged by the armoured trucks that had carried them there – the closest point to Mosul they had reached before an assault on Iraq’s second largest city.

For a few days early last month, the offensive looked like it already might be under way. But that soon changed when the Iraqis, trained by US forces, were quickly ousted from al-Nasr, the first town they had seized. There were about 25 more small towns and villages, all occupied by Isis, between them and Mosul. And 60 miles to go.

Behind the Iraqis, the Kurdish peshmerga remained dug into positions near the city of Makhmour that had marked the frontline since not long after Mosul was seized in June 2014. The war had been theirs until the national army arrived. The new partnership is not going well.

On both sides, there is a belief that what happens on the road to Mosul will not only define the course of the war but also shape the future of Iraq. And, despite the high stakes, planning for how to take things from here is increasingly clouded by suspicion and enmity. [Continue reading…]

A soldier’s challenge to the president

In an editorial, the New York Times says: Capt. Nathan Michael Smith, who is 28, is helping wage war on the Islamic State as an Army intelligence officer deployed in Kuwait. He is no conscientious objector. Yet he sued President Obama last week, making a persuasive case that the military campaign is illegal unless Congress explicitly authorizes it.

“When President Obama ordered airstrikes in Iraq in August 2014 and in Syria in September 2014, I was ready for action,” he wrote in a statement attached to the lawsuit. “In my opinion, the operation is justified both militarily and morally.” But as his suit makes clear, that does not make it legal.

Constitutional experts and some members of Congress have also challenged the Obama administration’s thin legal rationale for using military force in Iraq and Syria. The Federal District Court for the District of Columbia should allow the suit to move forward to force the White House and Congress to confront an important question both have irresponsibly skirted.

The 1973 War Powers Resolution requires that the president obtain “specific statutory authorization” soon after sending troops to war. Mr. Obama’s war against the Islamic State, also known as ISIS and ISIL, was billed as a short-term humanitarian intervention when it began in August 2014. The president and senior administration officials repeatedly asserted that the United States would not be dragged back into a Middle East quagmire. The mission, they vowed, would not involve “troops on the ground.” Yet the Pentagon now has more than 4,000 troops in Iraq and 300 in Syria. Last week’s combat death of a member of the Navy SEALs, Special Warfare Operator First Class Charles Keating IV, underscored that the conflict has escalated, drawing American troops to the front lines.

“We keep saying it’s supposed to be advising that we’re doing, and yet we’re losing one kid at a time,” Phyllis Holmes, Petty Officer Keating’s grandmother, told The Times.

Asked on Thursday about the lawsuit, the White House press secretary, Josh Earnest, said it raised “legitimate questions for every American to be asking.” The administration has repeatedly urged Congress to pass a war authorization for the war against the Islamic State. It currently relies on the authorization for the use of military force passed in 2001 for the explicit purpose of targeting the perpetrators of the Sept. 11 attacks, which paved the way for the invasion of Afghanistan.

“One thing is abundantly clear: Our men and women in uniform and our coalition partners are on the front lines of our war against ISIL, while Congress has remained on the sidelines,” the White House spokesman Ned Price said in an email.

Yet, the White House has enabled Congress to shirk its responsibility by arguing that a new war authorization would be ideal but not necessary. Administration officials could have forced Congress to act by declaring that it could not rely indefinitely on the Afghanistan war authorization and giving lawmakers a deadline to pass a new law.

By failing to pass a new one, Congress and the administration are setting a dangerous precedent that the next president may be tempted to abuse. That is particularly worrisome given the bellicose temperament of Donald Trump, the likely Republican nominee.

It is not too late to act before the presidential election in November. The Senate majority leader, Mitch McConnell, and House Speaker Paul Ryan have shown little interest in passing an authorization. They should feel compelled to heed the call of a young deployed soldier who is asking them to do their job.

The war against ISIS hits hurdles just as the U.S. military gears up

The Washington Post reports: After months of unexpectedly swift advances, the U.S.-led war against the Islamic State is running into hurdles on and off the battlefield that call into question whether the pace of recent gains can be sustained.

Chaos in Baghdad, the fraying of the cease-fire in Syria and political turmoil in Turkey are among some of the potential obstacles that have emerged in recent weeks to complicate the prospects for progress. Others include small setbacks for U.S.-allied forces on front lines in northern Iraq and Syria, which have come as a reminder that a strategy heavily reliant on local armed groups of varying proficiency who are often at odds with one another won’t always work.

When President Obama first ordered U.S. warplanes into action against the extremists sweeping through Iraq and Syria in 2014, U.S. officials put a three- to five-year timeline on a battle they predicted would be hard. After a rocky start, officials say they are gratified by the progress made, especially over the past six months.

Since the recapture of the northern Iraqi town of Baiji last October, Islamic State defenses have crumbled rapidly across a wide arc of territory. In Syria, the important hub of Shadadi was recaptured with little resistance in February, while in Iraq, Sinjar, Ramadi, Hit and, most recently, the town of Bashir have fallen in quick succession, lending hope that the militants are on the path to defeat.

“So far, in terms of what we had hoped to do, we are pretty much on track,” said a U.S. official who spoke on the condition of anonymity in order to discuss sensitive subjects. “We’re actually a little bit ahead of where we wanted to be.”

The fight, however, is entering what Pentagon officials have called a new and potentially harder phase, one that will entail a deeper level of U.S. involvement but also tougher targets.

In an attempt to ramp up the tempo of the war, the U.S. military is escalating its engagement, dispatching an additional 450 Special Operations forces and other troops to Syria and Iraq, deploying hundreds of Marines close to the front lines in Iraq and bringing Apache attack helicopters and B-52s into service for the air campaign.

The extra resources are an acknowledgment, U.S. officials say, that the war can’t be won without a greater level of American involvement. The targets that lie ahead are those that are most important to the militants’ self-proclaimed caliphate, including their twin capitals of Raqqa in Syria and Mosul in Iraq and, to a lesser extent, Fallujah, a key concern because of its proximity to Baghdad. [Continue reading…]

The pendulum of American power

Having been exercised with the imperial hubris of the neoconservatives, American power thereby overextended was inevitably going to swing in the opposite direction. What was not inevitable was that an administration when forced to deal with current events would cling so persistently to the past.

Through the frequent use of a number of catch phrases — “we need to look forward,” his promise “to end the mindset that got us into war,” and so forth — Barack Obama presented his administration as one that would unshackle the U.S. from the misadventures of his predecessor.

Nevertheless, Ben Rhodes, Obama’s closest adviser helping him craft this message, has a mindset in 2016 that shows no signs of having evolved in any significant way since he was on the 2008 campaign trail. As one of the lead authors of the 2006 Iraq Study Group report, Rhodes became and remains fixated on his notion of Iraq.

In a New York Times magazine profile of Rhodes, David Samuels writes:

What has interested me most about watching him and his cohort in the White House over the past seven years, I tell him, is the evolution of their ability to get comfortable with tragedy. I am thinking specifically about Syria, I add, where more than 450,000 people have been slaughtered.

“Yeah, I admit very much to that reality,” he says. “There’s a numbing element to Syria in particular. But I will tell you this,” he continues. “I profoundly do not believe that the United States could make things better in Syria by being there. And we have an evidentiary record of what happens when we’re there — nearly a decade in Iraq.”

Iraq is his one-word answer to any and all criticism. I was against the Iraq war from the beginning, I tell Rhodes, so I understand why he perpetually returns to it. I also understand why Obama pulled the plug on America’s engagement with the Middle East, I say, but it was also true as a result that more people are dying there on his watch than died during the Bush presidency, even if very few of them are Americans. What I don’t understand is why, if America is getting out of the Middle East, we are apparently spending so much time and energy trying to strong-arm Syrian rebels into surrendering to the dictator who murdered their families, or why it is so important for Iran to maintain its supply lines to Hezbollah. He mutters something about John Kerry, and then goes off the record, to suggest, in effect, that the world of the Sunni Arabs that the American establishment built has collapsed. The buck stops with the establishment, not with Obama, who was left to clean up their mess.

In this regard — “their ability to get comfortable with tragedy” — Rhodes and Obama mirror mainstream America which views the mess in the Middle East as being beyond America’s power to repair.

The fact that the U.S. bears a major portion of the blame in precipitating the region’s unraveling, is perversely presented as the reason the U.S. should now limit its involvement.

What, it’s reasonable to ask, does Iraq actually represent from this vantage point?

Wasted American lives? Wasted U.S. dollars? The destructive effect of American imperial power?

Is Iraq just a prism through which Americans look at America?

Is Iraq merely America’s shadow, or is there room for Iraqis anywhere in this picture?

What Samuel’s describes as this administration’s willingness to accept tragedy can also be seen as the required measure of indifference that makes it possible to look the other way.

The desire to make things better in Syria and Iraq is not contingent solely on an assessment of U.S. capabilities; it is more importantly a reflection of the degree to which Syrian and Iraqi lives matter to Americans.

The evidentiary record clearly shows that the scale of this tragedy all too accurately reflects the breadth of American indifference.

The only way to solve Iraq’s political crisis

Zaid al-Ali writes: With the Islamic State still in control of large parts of the country and oil prices depressed, Iraq is on the verge of a meltdown. But instead of working to solve the country’s problems, Iraq’s political class has been consumed by a power struggle. Last weekend, protesters in Baghdad lost their patience and stormed the Parliament building, threatening further action if serious reform is not enacted soon.

This eruption was a long time coming. Last August, Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi promised to improve government services and eliminate corruption. Unsurprisingly, he has failed to deliver. In response, protesters have demanded a new government and the abandonment of the sectarian quota system that has underpinned Iraqi governments since 2003. Mr. Abadi has tried to respond by putting forward a “technocratic” cabinet, but he hasn’t been able to get it approved by Parliament.

Ordinary Iraqis are furious. Moktada al-Sadr, the Shiite cleric who has long acted as a leader of Iraq’s underclass, has tried to capitalize on this by leading the protest movement. But even he cannot control the anger Iraqis feel toward their leaders.

The cause of Iraq’s political paralysis is neither ideological nor sectarian. In fact, most of the main actors in the continuing dispute are Shiite Islamists. The disagreement is instead based on mutual distrust, which is fueled by the incompetence and corruption that have formed the basis of Iraq’s political system since 2003. That dynamic has made it impossible for state institutions to present any viable solutions to the crisis.

Some Iraqi and American officials, including Vice President Joseph R. Biden Jr., have expressed hope that Mr. Abadi, at the head of a new government, can turn the situation around. They are missing the point. Even if a new government is formed, new ministers have to be approved by the Parliament, which insists on nominating the same crop of ineffectual, corrupt former exiles who have been running the country into the ground. More important, a new government would be beholden to the corrupt, sectarian Parliament. Making the argument that a new government can design, pass and carry out comprehensive governance reform is either delusional or an attempt to punt.

The only way out of the current stalemate is to inject new blood into the country’s political class. [Continue reading…]

An army captain takes Obama to court over war on ISIS

The New York Times reports: A 28-year-old Army officer on Wednesday sued President Obama over the legality of the war against the Islamic State, setting up a test of Mr. Obama’s disputed claim that he needs no new legal authority from Congress to order the military to wage that deepening mission.

The plaintiff, Capt. Nathan Michael Smith, an intelligence officer stationed in Kuwait, voiced strong support for fighting the Islamic State but, citing his “conscience” and his vow to uphold the Constitution, he said he believed that the mission lacked proper authorization from Congress.

“To honor my oath, I am asking the court to tell the president that he must get proper authority from Congress, under the War Powers Resolution, to wage the war against ISIS in Iraq and Syria,” he wrote.

The legal challenge comes after the death of the third American service member fighting the Islamic State and as Mr. Obama has decided to significantly expand the number of Special Operations ground troops he has deployed to Syria aid rebels there. [Continue reading…]

How U.S. troops fight ISIS while Obama plays down their role in combat

The New York Times reports: The battle in Teleskof began early Tuesday when volleys of mortar shells and blasts from rocket-propelled grenades disrupted meetings that the SEALs were having in the town with officials from the pesh merga, the Kurdish force battling the Islamic State in northern Iraq. Soon, a force of more than 100 Islamic State fighters punched through Kurdish checkpoints and overwhelmed the defenses on the southern edge of Teleskof, a largely Christian town about 14 miles north of Mosul.

The fighters from the Islamic State, also known as ISIS or ISIL, had taken the town by surprise, forcing many local fighters to retreat north of the town as it was overrun. The attackers “were able to very covertly assemble enough force” to “sprint towards Teleskof,” said Col. Steve Warren, the American military spokesman in Baghdad.

The SEALs were grossly outnumbered, and radioed that they were in a “troops in contact” situation — military jargon for a firefight. Colonel Warren said that American fighter planes, bombers and drones were sent to the town, along with a second group of SEALs. That group included Petty Officer Keating.

Matthew VanDyke, who runs a security firm, Sons of Liberty International, that is training local Iraqi forces — the Nineveh Plain Forces — said that the SEALs arrived in a convoy of sport utility vehicles from the north and drove directly into Teleskof.

“They went directly into combat,” he said.

Mr. VanDyke said that one of the trucks in the SEAL convoy appeared to get hit by a rocket- propelled grenade, and that the SEALs then got out of the S.U.V.s and went further into the town on foot.

A pitched battle continued, with the SEALs moving among buildings in the town and calling in airstrikes. About 9:30 a.m., Colonel Warren said, one of the SEAL team members radioed for medical help. Petty Officer Keating had been shot by an Islamic State sniper in the side, in an area not covered by his bulletproof vest.

Two Black Hawk helicopters arrived, drawing fire from Islamic State fighters, but were able to evacuate Petty Officer Keating to the American military’s medical mission in Erbil. He was pronounced dead shortly afterward.

The SEALs eventually pulled out of the town after they ran out of ammunition, Mr. VanDyke said.

Eventually, several hundred Kurdish pesh merga and other local fighters were able to mass for a counteroffensive. By the end of the day, those militias had managed to expel the Islamic State fighters from Teleskof.

Although American officials have used linguistic contortions for months to present the American military role in Iraq as something other than direct combat, Mr. Carter did not hesitate on Tuesday to call Petty Officer Keating’s death a “combat death.” [Continue reading…]