Peter Beinart writes: Now that he’s dead, and can cause no more trouble, Nelson Mandela is being mourned across the ideological spectrum as a saint. But not long ago, in Washington’s highest circles, he was considered an enemy of the United States. Unless we remember why, we won’t truly honor his legacy.

In the 1980s, Ronald Reagan placed Mandela’s African National Congress on America’s official list of “terrorist” groups. In 1985, then-Congressman Dick Cheney voted against a resolution urging that he be released from jail. In 2004, after Mandela criticized the Iraq War, an article in National Review said his “vicious anti-Americanism and support for Saddam Hussein should come as no surprise, given his longstanding dedication to communism and praise for terrorists.” As late as 2008, the ANC remained on America’s terrorism watch list, thus requiring the 89-year-old Mandela to receive a special waiver from the secretary of State to visit the U.S.

From their perspective, Mandela’s critics were right to distrust him. They called him a “terrorist” because he had waged armed resistance to apartheid. They called him a “communist” because the Soviet Union was the ANC’s chief external benefactor and the South African Communist Party was among its closest domestic allies. More fundamentally, what Mandela’s American detractors understood is that he considered himself an opponent, not an ally, of American power. And that’s exactly what Mandela’s American admirers must remember now. [Continue reading…]

Category Archives: South Africa

Mandela was never a revolutionary, always a radical

Gary Younge writes: A fitting way to commemorate Nelson Mandela is to describe his arrival in the townships during the first democratic elections in 1994. The crowds travelled up to 100 miles in cattle trucks or minibuses to get to places that apartheid had deliberately made remote and barren. Then they waited for hours, in a ramshackle stadium with little shade. Despite being punctual in his personal life, Mandela on the campaign trail was always late: a victim of overambitious scheduling and inefficient minders.

Finally, the crowds saw his cavalcade throw up dust in the distance, and they began to sing the campaign song Sekunjalo Ke Nako (Now is the Time). Everyone started to dance, ululations and cheers growing in intensity. Many of those present had not seen Mandela even on TV, and knew his face only from posters and newspaper pictures. Flags and placards hoisted above heads created a ripple at first, then a wave of excitement on a sea of black, gold and green.

The rush of energy did not subside until Mandela had taken the stage half an hour later. By then the crowd had got what it came for – proximity, a sighting, to be present in history. For hours after the rally, people walking home from the stadium punched the air and shouted “amandla” (“power”) at passing cars.

The problem with personifying a national, political aspiration, as Mandela did, is that it becomes difficult to see where the man starts and the movement ends. [Continue reading…]

Desmond Tutu on Nelson Mandela: ‘Prison became a crucible’

Desmond Tutu writes: For 27 years, I knew Nelson Mandela by reputation only. I had seen him once, in the early 1950s, when he came to my teacher-training college to judge a debating contest. The next time I saw him was in 1990.

When he came out of prison, many people feared he would turn out to have feet of clay. The idea that he might live up to his reputation seemed too good to be true. A whisper went around that some in the ANC said he was a lot more useful in jail than outside.

When he did come out, the most extraordinary thing happened. Even though many in the white community in South Africa were still dismissing him as a terrorist, he tried to understand their position. His gestures communicated more eloquently than words. For example, he invited his white jailer as a VIP guest to his inauguration as president, and he invited the prosecutor in the Rivonia trial to lunch.

What incredible acts of magnanimity these were. His prosecutor had been quite zealous in pushing for the death penalty. Mandela also invited the widows of the Afrikaner political leaders to come to the president’s residence. Betsie Verwoerd, whose husband, HF Verwoerd, was assassinated in 1966, was unable to come because she was unwell. She lived in Oranje, where Afrikaners congregated to live, exclusively. And Mandela dropped everything and went to have tea with her, there, in that place.

He had an incredible empathy. During the negotiations that led up to the first free elections, the concessions he was willing to make were amazing. Chief Buthelezi wanted this, that and the other, and at every single point Madiba would say: yes, that’s OK. He was upset that many in the ANC said Inkatha was not a genuine liberation movement. He even said that he was ready to promise Buthelezi a senior cabinet position, which was not something he had discussed with his colleagues. He did this to ensure that the country did not descend into a bloodbath. [Continue reading…]

Nelson Mandela: a leader above all others

In an editorial, The Guardian says: When Helen Suzman went to see Nelson Mandela on Robben Island in 1967, the first prisoner she encountered was a man called Eddie Daniels, who told her: “Yes, we know who you are. Don’t waste time talking to us. Go and talk to Mandela at the end of the row. He’s our leader.” Daniels’s absolute certainty struck Suzman very forcibly. Although Daniels did not spell it out, she learned later that the prison administration had tried to arrange her tour so that she would not reach Mandela’s cell before her limited time on Robben ran out.

She took the advice, made her way to Mandela’s cell, and found there a quietly eloquent and direct man of imposing physique and great natural authority. Eddie Daniels was of course right: Mandela was indeed the leader, not only of the detainees in the island prison, but of the South African liberation movement as a whole. He had mentors and partners, some in detention with him, some in exile, and some enduring a harassed and persecuted life in South Africa itself, and he had rivals inside and outside the African National Congress.

But he was indubitably the man who came, above all others, to symbolise the struggle of the ANC, from the time when it seemed to have collapsed under the assaults of the apartheid state, to the time of its final successes, when that same state found itself pleading with the ANC to enter a new era in which the structures of oppression would be liquidated.

Yet this leadership, even if we define it as moral rather than practical, remains ultimately something of a mystery. Mandela was not able, during 27 years in prison, to exercise sustained operational control or to take a regular part in ANC decision-making, except toward the very end, when he negotiated with FW de Klerk.

Before he went to jail, his record was of brave failure rather than of significant victory. His attempts, during his early years, to wage, along with others, a legal and non-violent campaign for black rights were stymied by a government which was not only unresponsive but positively preferred to push the ANC into clandestine activity so that it could fragment and criminalise the movement. His reluctant conversion to the military path ended abruptly when he was arrested within days of returning to South Africa to pursue the armed struggle. As a civil rights leader, he was ineffective. As a short-lived guerrilla leader, he was an amateur. And when, released from prison, he became the first president of the new South Africa, he was often inattentive, he discarded his once radical views on the economy, and, arguably, he endorsed the wrong man as his successor. To set against that, he insisted on respect for the judgments of the South African Constitutional Court even when they upset the ANC’s plans, and he refused to support the death penalty.

Mandela was far from alone among 20th-century liberation leaders in achieving stature in prison. [Continue reading…]

Nelson Mandela: we are blessed to have shared our lifetime with a colossus

Justice Malala writes: Nelson Mandela, global hero, died on Thursday night. We had steeled ourselves for it in the months of his hospitalisation over the past year and half. Yet, we are in shock.

We mourn him. We mourn him because in his 95 years, Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela has taught us how to live.

He taught us to strive for what is good and right, even as we ourselves stumble; to strain for perfection, even as we are caught up in our own flawed lives; to put the poor and downtrodden at the centre of our endeavours, even as we reach for the good life.

As he lay in hospital for months this year, Mandela taught us yet another lesson: just as we have been blessed with the gift of his presence, so too must we accept his inevitable departure. It is the most terrible of Biblical injunctions to perceive, but today it is stark: there is a time to live, and a time to die. Today we face the heartbreaking reality of the latter.

Over the past six months the news coming out of Pretoria had been the gravest it had ever been: the presidency had used the word “critical”; the family was sombre and mournful even as it was divided. The man whose walk to freedom was so long, so painful, so inspirational, was well on in his last journey.

Outside the hospital, passersby stopped and stared at the massed international and local media. “He is old. He must go,” said one to me as, like so many other journalists, we waited outside the hospital for word. It is a refrain that was heard often, at the hospital and elsewhere, even as far away as his home in Qunu. We could not bear to think of Mandela, a man who endured so much in pursuit of all our freedom, being in pain.

The heartbreaking reality, as one of our great poets, Chris van Wyk, once put it, is that it was time to go home, now. It is time to go home. [Continue reading…]

Nelson Mandela: Freedom fighter — 1918-2013

In June, Gary Younge wrote: Shortly before Nelson Mandela stepped down as president of South Africa in 1999, racial anxiety was a lucrative business. At the public library in the affluent area of Sandton, I attended a session at which an emigration consultant, John Gambarana, warned a hundred-strong, mostly white audience of the chaos and mayhem to come. Holding up a book by broadcaster Lester Venter called When Mandela Goes, he told them, “People, this book is a wake-up call. The bad news is [when Mandela leaves] the pawpaw’s really going to hit the fan. The good news is the fan probably won’t be working.”

And so it was that, even in the eyes of those who made a living peddling fear, less than a decade after his release from prison, Mandela had been transformed from terrorist boogeyman to national savior.

White South Africa has come to embrace him in much the same way that most white Americans came to accept Martin Luther King Jr.: grudgingly and gratefully, retrospectively, selectively, without grace but with considerable guile. By the time they realized that their dislike of him was spent and futile, he had created a world in which admiring him was in their own self-interest. Because, in short, they had no choice.

As the last apartheid leader, F.W. de Klerk—who had lost the election to Mandela—told me that same year, “The same mistakes that we made were still being made in the United States and the ex-colonies. Then we carried them on for around twenty years longer.” There are myriad differences between apartheid South Africa and America under segregation. But on that point, if little else, de Klerk was absolutely right. Neither the benefits of integration nor the urgency with which it was demanded were obvious to most Americans during King’s time. A month before the March on Washington in 1963, 54 percent of whites thought the Kennedy administration was “pushing racial integration too fast.” [Continue reading…]

Video — South Africa’s mine shooting: Who is to blame?

How the Israel lobby defended Israel’s military ties to apartheid South Africa

In a review of Sasha Polakow-Suransky’s new book, The Unspoken Alliance: Israel’s Secret Relationship with Apartheid South Africa, Glenn Frankel describes how spokesmen for American Jewish organizations acted as apologists or dupes for Israel’s arms sales to the apartheid state.

In the early days of the arms supply pact, Israel could argue that many Western countries, including the United States, had similar surreptitious relationships with the apartheid regime. But by 1980 Israel was the last major violator of the arms embargo. It stuck with South Africa throughout the 1980s when the regime clung to power in the face of international condemnation and intense rounds of political unrest in the black townships.

By 1987 the apartheid regime was struggling to cope with the combination of internal unrest and international condemnation to the point where even Israel was forced to take notice. A key motivator was Section 508, an amendment to the anti-apartheid sanctions bill that passed the U.S. Congress in 1986 and survived President Ronald Reagan’s veto. It required the State Department to produce an annual report on countries violating the arms embargo. The first one, issued in April 1987, reported that Israel had violated the international ban on arm sales “on a regular basis.” The report gave South Africa’s opponents within the Israeli government and their American Jewish allies ammunition to force Israel to adapt a mild set of sanctions against South Africa. I was in Jerusalem when Israel admitted publicly for the first time that it had significant military ties with South Africa and pledged not to enter into any new agreements — which meant, of course, that existing agreements would be maintained. It was, writes Polakow-Suransky, “little more than a cosmetic gesture.”

From the start, spokesmen for American Jewish organizations acted as apologists or dupes for Israel’s arms sales. Moshe Decter, a respected director of research for the American Jewish Committee, wrote in the New York Times in 1976 that Israel’s arms trade with South Africa was “dwarfed into insignificance” compared to that of other countries and said that to claim otherwise was “rank cynicism, rampant hypocrisy and anti-Semitic prejudice.” In a March 1986 debate televised on PBS, Rabbi David Saperstein, a leader of the Reform Jewish movement and outspoken opponent of apartheid, claimed Israeli involvement with South Africa was negligible. He conceded that there may have been arms sales during the rightist Likud years in power from 1977 to 1984, but stated that under Shimon Peres, who served as prime minister between 1984 and 1986, “there have been no new arms sales.” In fact, some of the biggest military contracts and cooperative ventures were signed during Peres’s watch.

The Anti-Defamation League participated in a blatant propaganda campaign against Nelson Mandela and the ANC in the mid 1980s and employed an alleged “fact-finder” named Roy Bullock to spy on the anti-apartheid campaign in the United States — a service he was simultaneously performing for the South African government. The ADL defended the white regime’s purported constitutional reforms while denouncing the ANC as “totalitarian, anti-humane, anti-democratic, anti-Israel, and anti-American.” (In fairness, the ADL later changed its tune. After his release in 1990, Mandela met in Geneva with a number of American Jewish leaders, including ADL president Abe Foxman, who emerged to call the ANC leader “a great hero of freedom.”)

Polakow-Suransky is no knee-jerk critic of Israel, and he tells his story more in sorrow than anger. He grants that the secret alliance had its uses. To the extent it enhanced Israel’s security and comfort zone, it may have helped pave the path to peace efforts. Elazar Granot, a certified dove who is a former left-wing Knesset member and ambassador to the new South Africa, says as much. “I had to take into consideration that maybe Rabin and Peres were able to go to the Oslo agreements because they believed that Israel was strong enough to defend itself,” he tells the author. “Most of the work that was done — I’m talking about the new kinds of weapons — was done in South Africa.”

Polakow-Suransky sees in the excoriation of Jimmy Carter’s 2006 book, Palestine: Peace Not Apartheid by American Jewish leaders an echo of their reflexive defense of Israel vis á vis South Africa in the 1970s and 1980s. The author himself draws uncomfortable parallels between apartheid and Israel’s occupation of the West Bank and Gaza, noting that both involved the creation of a system that stifled freedom of movement and labor, denied citizenship and produced homelessness, separation, and disenfranchisement. As the Palestinian population continues to grow and eventually becomes the majority — and Jews the minority — in the land between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean, the parallels with apartheid may become increasingly uncomfortable. Even Prime Minister Ehud Olmert agreed, observing in 2007 that if Israel failed to negotiate a two-state solution with the Palestinians, it would inevitably “face a South African-style struggle for equal voting rights.”

“The apartheid analogy may be inexact today,” Polakow-Suransky warns, “but it won’t be forever.”

Sasha Polakow-Suransky on Al Jazeera

Israel and apartheid: a marriage of convenience and military might

Chris McGreal, in a series of reports triggered by the publication of Sasha Polakow-Suransky’s new book, The Unspoken Alliance, writes:

For years after its birth, Israel was publicly critical of apartheid and sought to build alliances with the newly independent African states through the 1960s.

But after the 1973 Yom Kippur war, African governments increasingly came to look on the Jewish state as another colonialist power. The government in Jerusalem cast around for new allies and found one in Pretoria. For a start, South Africa was already providing the yellowcake essential for building a nuclear weapon.

By 1976, the relationship had changed so profoundly that South Africa’s prime minister, John Vorster, could not only make a visit to Jerusalem but accompany Israel’s two most important leaders, Yitzhak Rabin and Shimon Peres, to the city’s Holocaust memorial to mourn the six million Jews murdered by the Nazis.

Neither Israeli appears to have been disturbed by the fact that Vorster had been an open supporter of Hitler, a member of South Africa’s fascist and violently antisemitic Ossewabrandwag and that he was interned during the war as a Nazi sympathiser.

Rabin hailed Vorster as a force for freedom and at a banquet toasted “the ideals shared by Israel and South Africa: the hopes for justice and peaceful coexistence”.

How Israel offered nuclear weapons to apartheid South Africa

Secret agreement signed by South Africa's minister of defence PW Botha and Israel's minister of defence Shimon Peres in 1975.

Secret South African documents reveal that Israel offered to sell nuclear warheads to the apartheid regime, providing the first official documentary evidence of the state’s possession of nuclear weapons.

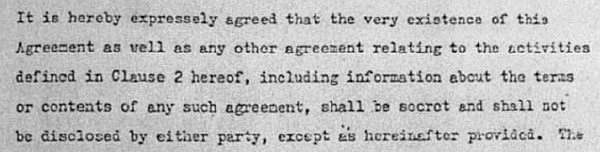

The “top secret” minutes of meetings between senior officials from the two countries in 1975 show that South Africa’s defence minister, PW Botha, asked for the warheads and Shimon Peres, then Israel’s defence minister and now its president, responded by offering them “in three sizes”. The two men also signed a broad-ranging agreement governing military ties between the two countries that included a clause declaring that “the very existence of this agreement” was to remain secret.

The documents, uncovered by an American academic, Sasha Polakow-Suransky, in research for a book on the close relationship between the two countries, provide evidence that Israel has nuclear weapons despite its policy of “ambiguity” in neither confirming nor denying their existence.

The Israeli authorities tried to stop South Africa’s post-apartheid government declassifying the documents at Polakow-Suransky’s request and the revelations will be an embarrassment, particularly as this week’s nuclear non-proliferation talks in New York focus on the Middle East.

They will also undermine Israel’s attempts to suggest that, if it has nuclear weapons, it is a “responsible” power that would not misuse them, whereas countries such as Iran cannot be trusted.

South African documents show that the apartheid-era military wanted the missiles as a deterrent and for potential strikes against neighbouring states.

The documents show both sides met on 31 March 1975. Polakow-Suransky writes in his book published in the US this week, The Unspoken Alliance: Israel’s secret alliance with apartheid South Africa. At the talks Israeli officials “formally offered to sell South Africa some of the nuclear-capable Jericho missiles in its arsenal”.

Among those attending the meeting was the South African military chief of staff, Lieutenant General RF Armstrong. He immediately drew up a memo in which he laid out the benefits of South Africa obtaining the Jericho missiles but only if they were fitted with nuclear weapons.

Israel’s dark past arming apartheid South Africa

A new attack on Judge Richard Goldstone is the latest effort in a campaign to direct attention away from his allegations that Israel committed war crimes in Gaza. In this instance though, questions about Goldstone’s record as a judge in apartheid South Africa are overshadowed by the Jewish state’s own role in helping support the racist policies of one of the cruelest regimes of the 20th century.

Israel’s dark past as a secret ally of the cruel apartheid regime in South Africa is revealed in an article by Sasha Polakow-Suransky (the author of a new book on the same subject).

The Israel-South Africa alliance began in earnest in April 1975 when then-Defense Minister Shimon Peres signed a secret security pact with his South African counterpart, P.W. Botha. Within months, the two countries were doing a brisk trade, closing arms deals totaling almost $200 million; Peres even offered to sell Pretoria nuclear-capable Jericho missiles. By 1979, South Africa had become the Israeli defense industry’s single largest customer, accounting for 35 percent of military exports and dwarfing other clients such as Argentina, Chile, Singapore, and Zaire.

High-level exchanges of military personnel soon followed. South Africans joined the Israeli chief of staff in March 1979 for the top-secret test of a new missile system. During Israel’s 1982 invasion of Lebanon, the Israeli army took South African Defense Force chief Constand Viljoen and his colleagues to the front lines, and Viljoen routinely flew visiting Israeli military advisors and embassy attachés to the battlefield in Angola where his troops were battling Angolan and Cuban forces.

There was nuclear cooperation, too: South Africa provided Israel with yellowcake uranium while dozens of Israelis came to South Africa in 1984 with code names and cover stories to work on Pretoria’s nuclear missile program at South Africa’s secret Overberg testing range. By this time, South Africa’s alternative sources for arms had largely dried up because the United States and European countries had begun abiding by the U.N. arms embargo; Israel unapologetically continued to violate it.

As for Goldstone’s record as “a hanging judge”, this is what he told the Jewish Chronicle:

“During the nine years I was a trial judge from 1980 to 1989, I sentenced two people to death for murder without extenuating circumstances.

“They were murders committed gratuitously during armed robberies. In the absence of extenuating circumstances the imposition of the death sentence was mandatory. My two assessors and I could find no extenuating circumstances in those two cases.

“While I was a judge in the Supreme Court of Appeal from 1990 to 1994, all executions were put on hold. However, automatic appeals still continued to come before the Supreme Court of appeal. We sat in panels of three and again, in the absence of extenuating circumstances, some of those appeals failed.”

He added: “It was a difficult moral decision taking an appointment during the Apartheid era. With regard to my role in those years I would refer you to the joint public statement issues in January by former Chief Justice Arthur Chaskalson, the first Chief Justice appointed by President Mandela, and George Bizos, Nelson Mandela’s lawyer and close friend for over 50 years.

In their statement, Chaskalson and Bizos wrote:

Not every judge appointed during the apartheid era was a supporter of apartheid. There were a number among them, including Goldstone, who accepted appointment to the Bench in the 1970s and 1980s in the belief that they could keep principles of the law alive. They included Michael Corbett, Simon Kuper, Gerald Friedman, HC Nicholas, George Colman, Solly Miller, John Milne, Andrew Wilson, John Didcott, Laurie Ackermann, Johann Kriegler and others.

There is a considerable body of evidence that they discharged their functions with courage and integrity. This is recognised in the report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which observed that “there were always a few lawyers (including judges, teachers and students) who were prepared to break with the norm”. Commenting on such judges, it says “they exercised their discretion in favour of justice and liberty wherever proper and possible . . . and [the judges, lawyers, teachers and students referred to] were influential enough to be part of the reason why the ideal of a constitutional democracy as the favoured form of government for a future South Africa continued to burn brightly throughout the darkness of the apartheid era”.

Goldstone was one of those judges. For instance, his decision in the case of S v Govender in 1986 that no ejectment order should be made against persons disqualified by the Group Areas Act from occupying premises reserved for the white group, without enquiring into whether alternative accommodation for such persons was available, was a blow to the apartheid regime and contributed substantially to that legislation becoming unenforceable in parts of the country.

As a judge of the Constitutional Court he concurred in the finding that the first draft of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa passed by the newly elected Constituent Assembly did not comply in certain respects with the 34 constitutional principles agreed to by the negotiating parties at Codesa.

He was the founding chairperson of the National Institute for Crime Prevention and the Reintegration of Offenders (Nicro), which looks after prisoners who have been released; he exercised his power as a judge (not often used by other judges) to visit prisoners in jail; he insisted on seeing political prisoners indefinitely detained to hear their complaints; and he intervened so as to allow doctors to see them and where possible to make representations that their release be considered.

After the release of Nelson Mandela he played an important role in persuading his colleagues on the Bench to accept the inevitable changes that were likely to take place in the political and judicial structures.

Former president FW de Klerk, with the concurrence of the then-president of the African National Congress, Nelson Mandela, appointed Goldstone as the chairperson of the commission to investigate what became known as hit-squads or third-force organisations within the army and the police.

His reports exposed high-ranking officers, who were obliged by De Klerk to resign, and other members of the security forces, and he made findings that police had unlawfully shot at unarmed protesters and recommended that they be charged with murder.

Threats to his life were made, and his name was on the hit list produced in court as part of the state case against the killers of Chris Hani in 1993.

Meanwhile, yesterday was a good day for Israel as it was invited to join the mostly white, Eurocentric, rich nations’ club, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Nothing better expresses the apartheid mentality at the heart of Zionism than Israel’s preference to belong to international organizations that are defined by exclusion rather than inclusion.

As Aluf Benn writes today in Haaretz:

Israel has always sought to become a member of international organizations where the Western bloc of nations enjoys a clear advantage. In the vast majority of UN institutions, for example, Israel is isolated and does not belong to any geographic group. So it can’t elect or be elected. But there are no Arab countries in the OECD and the only Muslim member is Turkey, which yesterday voted in support of the unanimous acceptance of Israel into the group.

Joining the OECD bolsters the approach of Netanyahu and Defense Minister Ehud Barak, who consider Israel “a villa in the jungle” – a small island of Western values and development in an Arab and Muslim sea. Now we’re in the club and the Palestinians, Egyptians and even the Saudis aren’t. They’re not even on the waiting list. In the OECD they can’t bother Israel with decisions condemning the occupation.