The New York Times reports: The [National Security] agency’s ability to efficiently mine metadata, data about who is calling or e-mailing, has made wiretapping and eavesdropping on communications far less vital, according to data experts. That access to data from companies that Americans depend on daily raises troubling questions about privacy and civil liberties that officials in Washington, insistent on near-total secrecy, have yet to address.

“American laws and American policy view the content of communications as the most private and the most valuable, but that is backwards today,” said Marc Rotenberg, the executive director of the Electronic Privacy Information Center, a Washington group. “The information associated with communications today is often more significant than the communications itself, and the people who do the data mining know that.”

In the 1960s, when the N.S.A. successfully intercepted the primitive car phones used by Soviet leaders driving around Moscow in their Zil limousines, there was no chance the agency would accidentally pick up Americans. Today, if it is scanning for a foreign politician’s Gmail account or hunting for the cellphone number of someone suspected of being a terrorist, the possibilities for what N.S.A. calls “incidental” collection of Americans are far greater.

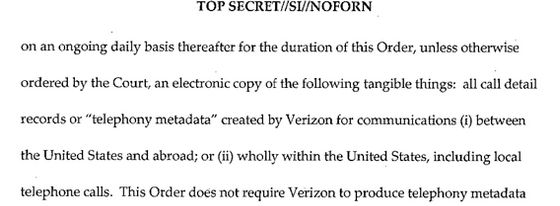

United States laws restrict wiretapping and eavesdropping on the actual content of the communications of American citizens but offer very little protection to the digital data thrown off by the telephone when a call is made. And they offer virtually no protection to other forms of non-telephone-related data like credit card transactions.

Because of smartphones, tablets, social media sites, e-mail and other forms of digital communications, the world creates 2.5 quintillion bytes of new data daily, according to I.B.M.

The company estimates that 90 percent of the data that now exists in the world has been created in just the last two years. From now until 2020, the digital universe is expected to double every two years, according to a study by the International Data Corporation.

Accompanying that explosive growth has been rapid progress in the ability to sift through the information.

When separate streams of data are integrated into large databases — matching, for example, time and location data from cellphones with credit card purchases or E-ZPass use — intelligence analysts are given a mosaic of a person’s life that would never be available from simply listening to their conversations. Just four data points about the location and time of a mobile phone call, a study published in Nature found, make it possible to identify the caller 95 percent of the time.

“We can find all sorts of correlations and patterns,” said one government computer scientist who spoke on condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to comment publicly. “There have been tremendous advances.”

Here’s a fantasy portrayal of how harvesting metadata can save lives. The storyteller is Palantir Technologies whose database integration system is reported to have become “an indispensable tool employed by the U.S. intelligence community in the war on terrorism.”

In October, a foreign national named Mike Fikri purchased a one-way plane ticket from Cairo to Miami, where he rented a condo. Over the previous few weeks, he’d made a number of large withdrawals from a Russian bank account and placed repeated calls to a few people in Syria. More recently, he rented a truck, drove to Orlando, and visited Walt Disney World by himself. As numerous security videos indicate, he did not frolic at the happiest place on earth. He spent his day taking pictures of crowded plazas and gate areas.

None of Fikri’s individual actions would raise suspicions. Lots of people rent trucks or have relations in Syria, and no doubt there are harmless eccentrics out there fascinated by amusement park infrastructure. Taken together, though, they suggested that Fikri was up to something. And yet, until about four years ago, his pre-attack prep work would have gone unnoticed. A CIA analyst might have flagged the plane ticket purchase; an FBI agent might have seen the bank transfers. But there was nothing to connect the two. Lucky for counterterror agents, not to mention tourists in Orlando, the government now has software made by Palantir Technologies, a Silicon Valley company that’s become the darling of the intelligence and law enforcement communities.

The day Fikri drives to Orlando, he gets a speeding ticket, which triggers an alert in the CIA’s Palantir system. An analyst types Fikri’s name into a search box and up pops a wealth of information pulled from every database at the government’s disposal. There’s fingerprint and DNA evidence for Fikri gathered by a CIA operative in Cairo; video of him going to an ATM in Miami; shots of his rental truck’s license plate at a tollbooth; phone records; and a map pinpointing his movements across the globe. All this information is then displayed on a clearly designed graphical interface that looks like something Tom Cruise would use in a Mission: Impossible movie.

As the CIA analyst starts poking around on Fikri’s file inside of Palantir, a story emerges. A mouse click shows that Fikri has wired money to the people he had been calling in Syria. Another click brings up CIA field reports on the Syrians and reveals they have been under investigation for suspicious behavior and meeting together every day over the past two weeks. Click: The Syrians bought plane tickets to Miami one day after receiving the money from Fikri. To aid even the dullest analyst, the software brings up a map that has a pulsing red light tracing the flow of money from Cairo and Syria to Fikri’s Miami condo. That provides local cops with the last piece of information they need to move in on their prey before he strikes.

Now let’s make a tiny tweak to this story: Fikri, mindful that it’s probably not wise to draw the attention of law enforcement, carefully observes all traffic regulations. He doesn’t get a speeding ticket and the CIA’s Palantir system is not triggered into action.

Shane Harris writes: To date, there have been practically no examples of a terrorist plot being pre-emptively thwarted by data mining these huge electronic caches. (Rep. Mike Rogers, chairman of the House Intelligence Committee, has said that the metadatabase has helped thwart a terrorist attack “in the last few years,” but the details have not been disclosed.)

When I was writing my book, The Watchers, about the rise of these big surveillance systems, I met analyst after analyst who said that data mining tends to produce big, unwieldy masses of potential bad actors and threats, but rarely does it produce a solid lead on a terrorist plot.

Those leads tend to come from more pedestrian investigative techniques, such as interviews and interrogations of detainees, or follow-ups on lists of phone numbers or e-mail addresses found in terrorists’ laptops. That shoe-leather detective work is how the United States has tracked down so many terrorists. In fact, it’s exactly how we found Osama bin Laden.

What the proponents of mass surveillance need to explain is how, given the existing scope of data gathering, the NSA did not intercept Tamerlan Tsarnaev and Dzhokhar Tsarnaev before they planted their bombs in Boston. Neither was Faisal Shahzad prevented from attempting to bomb Times Square.

What mass data collection is extremely effective in doing, is identifying trends — such as the emergence of a political movement. As a tool for suppressing political dissent, nothing could be more effective.

The Obama administration might not be in the business of large-scale political oppression, but what it is doing is putting in place and expanding the infrastructure of oppression.

Americans may never face a dramatic moment in which freedoms are suddenly stripped away, if instead we willingly abandon liberty, bit by bit, in favor of an illusory security.