US pours millions into anti-Taliban militias in Afghanistan

U.S. special forces are supporting anti-Taliban militias in at least 14 areas of Afghanistan as part of a secretive programme that experts warn could fuel long-term instability in the country.

The Community Defence Initiative (CDI) is enthusiastically backed by Stanley McChrystal, the US general commanding Nato forces in Afghanistan, but details about the programme have been held back from non-US alliance members who are likely to strongly protest.

The attempt to create what one official described as “pockets of tribal resistance” to the Taliban involves US special forces embedding themselves with armed groups and even disgruntled insurgents who are then given training and support.

In return for stabilising their local area the militia helps to win development aid for their local communities, although they will not receive arms, a US official said.

Special forces will be able to access money from a US military fund to pay for the projects. The hope is that the militias supplement the Nato and Afghan forces fighting the Taliban. But the prospect of re-empowering militias after billions of international dollars were spent after the US-led invasion in 2001 to disarm illegally armed groups alarms many experts. [continued…]

The sum we are already spending annually on Afghanistan is greater than its gross domestic product. Are there nonmilitary ways we could deploy that sum which would advance our goals as efficaciously? Would even forty thousand additional troops suffice for anything resembling the ambitious nation-building program that General Stanley McChrystal, the top military commander in Afghanistan, has proposed? (Counterinsurgency theory suggests that it would take more than ten times that many; would forty—or ten, or twenty—thousand be only a first installment?) Any counterinsurgency campaign, we’re told, requires a very long commitment. Is the voluntary association of democracies called NATO, organized to deter war more than to wage it, capable of sustaining a twenty or thirty years’ war? For that matter, does the United States—a decentralized populist democracy struggling with economic decline and political gridlock—have that capacity? And what about Pakistan?

The President has come under heavy criticism for taking the time to ponder the imponderables. “The urgent necessity,” a respected Washington columnist wrote the other day, “is to make a decision—whether or not it is right.” Really? Does the columnist suppose that a country unable to find the patience for weeks (even months) of thinking could summon the stamina for years (even decades) of killing and dying? What Obama seems to have discovered is that this is no longer the war that began eight years ago. That war was an act of retribution and prevention. But now who are we punishing? What are we preventing? The old narrative is broken. [continued…]

Militants could be invited to Afghan “Jirga”

Afghan President Hamid Karzai could invite militants to attend a “Loya Jirga,” or grand council meeting, aiming to seek peace and reconciliation with the Taliban, a spokesman said on Sunday.

The plans signal a more public effort to engage with militants during Karzai’s second term as leader, measures that Washington has encouraged in its counter-insurgency strategy.

Afghanistan’s constitution recognizes the Loya Jirga — Pashtu for grand assembly — as “the highest manifestation of the will of the people of Afghanistan.” [continued…]

Escaping Taliban may widen war as Pakistan pays cost

Taliban fleeing a Pakistani offensive are regrouping in the country’s northwest, threatening to spread and prolong a conflict that has strained the nation’s economy and may hamper efforts to attract foreign investment.

While Pakistan says its month-old offensive in South Waziristan has destroyed the largest Taliban sanctuary, some militants are falling back to Orakzai, a mountain region less than 16 kilometers (10 miles) south of Peshawar, the capital of North West Frontier Province, said Talat Masood, an independent military analyst in Islamabad.

Rising violence in the region last year prompted London- based Tullow Oil Plc to give up operational control of drilling operations near Orakzai. A wider conflict may make it harder to attract companies like Mol Nyrt., Hungary’s largest oil refiner, which this month started natural gas production in the province. [continued…]

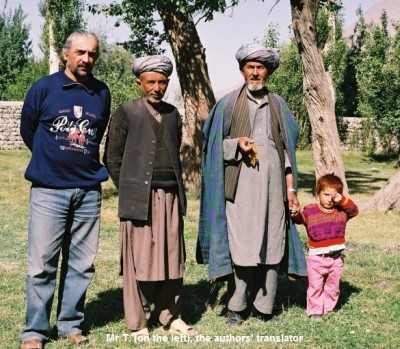

We entered Afghanistan from Tajikistan by walking unescorted across the no-man’s land at the Oxus River border station at Eshkashem. We were dressed as civilians and carried our own packs: no vehicles, no flak jackets, no body guards, just plain folks. We were, however, accompanied by our impressive guide and translator, whom we shall simply call Mr. T., a Tajik native of Khorug and a speaker of Tajik and Russian (he spent four years studying film at the academy in Moscow and, like all other Tajiks in his age group, served in the Russian army), as well as Dard; but his native language is Shugni, which is also widely spoken across the Oxus from Khorug in Afghanistan, as is Tajik: there are as many Tajiks (four and a half million) in Afghanistan as in Tajikistan. Then, too, Mr. T. had spent eleven years in Afghanistan working for Focus.

We entered Afghanistan from Tajikistan by walking unescorted across the no-man’s land at the Oxus River border station at Eshkashem. We were dressed as civilians and carried our own packs: no vehicles, no flak jackets, no body guards, just plain folks. We were, however, accompanied by our impressive guide and translator, whom we shall simply call Mr. T., a Tajik native of Khorug and a speaker of Tajik and Russian (he spent four years studying film at the academy in Moscow and, like all other Tajiks in his age group, served in the Russian army), as well as Dard; but his native language is Shugni, which is also widely spoken across the Oxus from Khorug in Afghanistan, as is Tajik: there are as many Tajiks (four and a half million) in Afghanistan as in Tajikistan. Then, too, Mr. T. had spent eleven years in Afghanistan working for Focus. Despite such diversity in the Wakhan Corridor, there was a unanimous belief that the Afghan government is simply an outrageous band of crooks on the take and that Hamid Karzai is chief among them. This disgust cut across all linguistic, age and belief groups. It was barely below the surface of any discussion, as was the question of when the “foreigners” would leave. There was no blaming the Russians, nor even our guide, Mr. T., who, as a Tajik, was clearly from the “wrong” side when talk turned to the Soviet era. The wreckage of that period is plain to see: discarded tank turrets decorate many of Eshkashem’s street corners. Most significantly, while there was a firm awareness of local pride of place, there was no patriotic fervor for an Afghanistan, seemingly a very alien concept for many.

Despite such diversity in the Wakhan Corridor, there was a unanimous belief that the Afghan government is simply an outrageous band of crooks on the take and that Hamid Karzai is chief among them. This disgust cut across all linguistic, age and belief groups. It was barely below the surface of any discussion, as was the question of when the “foreigners” would leave. There was no blaming the Russians, nor even our guide, Mr. T., who, as a Tajik, was clearly from the “wrong” side when talk turned to the Soviet era. The wreckage of that period is plain to see: discarded tank turrets decorate many of Eshkashem’s street corners. Most significantly, while there was a firm awareness of local pride of place, there was no patriotic fervor for an Afghanistan, seemingly a very alien concept for many.