How much credit does President Obama deserve for releasing the torture memos?

Glenn Greenwald argues:

Other than mildly placating growing anger over his betrayals of his civil liberties commitments (which, by the way, is proof of the need to criticize Obama when he does the wrong thing), there wasn’t much political gain for Obama in releasing these documents. And he certainly knew that, by doing so, he would be subjected to an onslaught of accusations that he was helping Al Qaeda and endangering American National Security. And that’s exactly what happened, as in this cliché-filled tripe from Hayden and Michael Mukasey in today’s Wall St. Journal, and this from an anonymous, cowardly “top Bush official” smearing Obama while being allowed to hide behind the Jay Bybee of journalism, Politico‘s Mike Allen.

But Obama knowingly infuriated the CIA, including many of his own top intelligence advisers; purposely subjected himself to widespread attacks from the Right that he was giving Al Qaeda our “playbook”; and he released to the world documents that conclusively prove how that the U.S. Government, at the highest levels, purported to legalize torture and committed blatant war crimes. There’s just no denying that those actions are praiseworthy. I understand the argument that Obama only did what the law requires. That is absolutely true. We’re so trained to meekly accept that our Government has the right to do whatever it wants in secret — we accept that it’s best that most things be kept from us — that we forget that a core premise of our government is transparency; that the law permits secrecy only in the narrowest of cases; and that it’s certainly not legal to suppress evidence of government criminality on the grounds that it is classified.

Still, as a matter of political reality, Obama had to incur significant wrath from powerful factions by releasing these memos, and he did that. That’s an extremely unusual act for a politician, especially a President, and it deserves praise.

Really? I honestly don’t see it and I think that drawing a distinction between the act of releasing the memos and the act of throwing out a lifeline to those who might face prosecution is a way of decoupling what were actually interlocking actions.

The Obama administration had already stalled on releasing the memos. Had they continued to do so they would have put themselves in the position of appearing to be complicit in covering up a criminal conspiracy.

Central to that conspiracy was an effort to use evidence derived from observing the effects of the US military’s Survival, Evasion, Resistance and Escape (SERE) training.

In assessing the potential risk involved in the use of torture techniques such as waterboarding, the Department of Justice’s Office of Legal Council rested heavily on the proposition that if no lasting harm had been done to SERE trainees then neither would terrorist suspects be at risk.

In his memo to John Rizzo, Acting General Council of the CIA, Assistant Attorney General Jay Bybee wrote:

…the information derived from SERE training bears upon the impact of the use of the individual techniques and upon their use as a course of conduct. You have found that the use of these methods together or separately, including the use of the waterboard, has not resulted in any negative long-term mental health consequences. The continued use of these methods without mental health consequences to the trainees indicates that it is highly improbable that such consequences would result here. Because you conducted the due diligence to determine that these procedures, either alone or in combination, do not produce prolonged mental harm, we believe that you do not meet the specific intent requirement necessary to violate Section 2340A [the statute prohibiting the use of torture].

But the gaping hole in that argument was acknowledged by Steven Bradbury, a member of Bybee’s own staff, three years later:

Although we refer to the SERE experience below, we note at the outset an important limitation on reliance on that experience. Individuals undergoing SERE training are obviously in a very different situation from detainees undergoing interrogation; SERE trainees know it is part of a training program, not a real-life interrogation regime, they presumably know it will last only a short time, and they presumably have assurances that they will not be significantly harmed by the training.

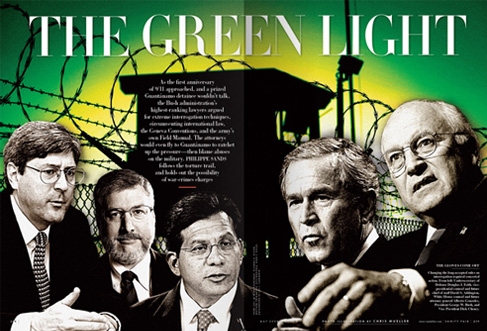

What was obvious to Bradbury in 2005 somehow eluded Bybee’s grasp in 2002. Maybe it was because Bybee had spent too much time in the company of the likes of Dick Cheney, David Addington and Donald Rumsfeld.

It was Rumsfeld who had famously asserted that as someone who worked standing up, he couldn’t see the harm in forcing someone else to remain standing for many hours — as though it was neither here nor there whether the person standing was also naked, chained in position and being held in secret in a foreign country.

The point — and this is really the core issue in the whole torture debate — is that there is and always has been only one pressure point against which force is applied in the practice of torture, that being, the human mind. Its aim is to break the mind without breaking the body. Its successful practice requires that whatever scars are left behind are not clearly visible.

If its up to Obama, America will now “move forward” and the scars of torture will remain invisible.

The CIA however is bracing itself for examination.

The Washington Post reports:

For the first time, officials said yesterday that they would provide legal representation at no cost to CIA employees subjected to international tribunals or inquiries from Congress. They also said they would indemnify agency workers against any financial judgments.

The announcement appeared to be designed to soothe concerns expressed by top intelligence officials, who argued in recent weeks that the graphic detail in the memos could bring unwanted attention to interrogators and deter others from joining government service.

CIA Director Leon E. Panetta told employees that the interrogation practices won approval from the highest levels of the Bush administration and that they had nothing to fear if they followed the legal guidance from the Justice Department.

“You need to be fully confident that as you defend the nation, I will defend you,” Panetta said.

John Demjanjuk, the former Nazi death camp guard who is awaiting deportation from the United States before being sent to Germany to face trial for his part in the Holocaust, is being defended by lawyers who argue that putting the 89-year-old on trial would cause him pain amounting to torture.

If he does end up on trial, his defense may well suggest that we no longer live in a world where the Nuremberg defense is untenable.

As Barack Obama and Leon Panetta seem to be saying, “I was just following orders,” has now become an honorable American justification for torture.