The Daily Beast reports: The Obama administration is withholding hundreds, perhaps even thousands of photographs showing the U.S. government’s brutal treatment of detainees, meaning that revelations about detainee abuse could well continue, possibly compounding the outrage generated by the Senate “torture report” now in the public eye.

Some photos show American troops posing with corpses; others depict U.S. forces holding guns to people’s heads or simulating forced sodomization. All of them could be released to the public, depending on how a federal judge in New York rules—and how hard the government fights to appeal. The government has a Friday deadline to submit to that judge its evidence for why it thinks each individual photograph should continue to be kept hidden away.

The photographs are part of a collection of thousands of images from 203 investigations into detainee abuse in Iraq and Afghanistan and represent one of the last known secret troves of evidence of detainee abuse. While the photos show disturbing images from the Bush administration’s watch, it is the Obama administration that has allowed them to remain buried — all with the help of a willing Congress. [Continue reading…]

Category Archives: torture

Rebecca Gordon: The torture wars

It came from the top and that’s never been a secret. The president authorized the building of those CIA “black sites” and the use of what came to be known as “enhanced interrogation techniques” and has spoken of this with a certain pride. The president’s top officials essentially put in an order at the Department of Justice for “legal” justifications that would, miraculously, transform those “techniques” into something other than torture. Its lawyers then pulled out their dictionaries and gave new meaning to tortured definitions of torture that could have come directly from the fused pens of Franz Kafka and George Orwell. In the process, they even managed to leave the definition of torture to the torturer. It was a performance for the ages.

Last week, former Vice President Dick Cheney, who only days after 9/11 claimed that the Bush administration was going to “work the dark side,” once again championed those techniques and the CIA agents who used them. It was a handy reminder of just what a would-be crew of tough-guy torture instigators he and his cohorts were. The legal veneer spread thinly over the program they set in motion was meant to provide only the faintest legal cover for the “gloves” they bragged about taking off, while obscuring the issue for the American public. After all, few in the rest of the world were likely to accept the idea that interrogation methods like waterboarding, or “the water torture” as it had once been known, were anything but torture. Even in this country, it had been accepted as just that. The Bush administration was, of course, helped in those years by a media that, when not cheerleading for torture, or actually lending the CIA a helpful hand, essentially banished the word from its vocabulary, unless it referred to heinously similar acts committed by countries we disliked.

All in all, it was an exercise in what the “last superpower,” the world’s “policeman,” could get away with in the backrooms of its police stations being jerry-built around the world. And some of the techniques used with a particular brutality were evidently first demonstrated to top officials in the White House itself.

Then, of course, the CIA went out and applied those “enhanced techniques” to actual human beings with abandon, as the newly released (and somewhat redacted) executive summary of the Senate Intelligence Committee’s “torture report” indicates. This was done even more severely than ordered (not that Cheney & Co. cared), including to a surprising number of captives that the CIA later decided were innocent of anything having to do with terror or al-Qaeda. All of this happened, despite a law this country signed onto prohibiting the use of torture abroad.

Although what I’ve just described is now generally considered The Torture Story here, it really was only part of it. The other part, also a CIA operation authorized at the highest levels, was “rendition” or “extraordinary rendition” as it was sometimes known. This was a global campaign of kidnappings, aided and abetted by 54 other countries, in which “terror suspects” (again often enough innocent people) were swept off the streets of major cities as well as the backlands of the planet and “rendered” to other countries, ranging from Libya and Syria to Egypt and Uzbekistan, places with their own handy torture chambers and interrogators already much practiced in “enhanced” techniques of one sort or another.

Moreover, those techniques migrated like a virus from the CIA and its “black sites” elsewhere in the U.S. imperium, most notoriously via Guantanamo to Abu Ghraib, the American-run prison in Iraq, where images of torture and abuse of a distinctly enhanced variety then migrated home as screensavers. What was done couldn’t have been more criminal in nature, whether judged by U.S. or international law. In its wake, its perpetrators, both the torturers and the kidnappers, were protected in a major way. Except for a few low-level figures at Abu Ghraib and one non-torturing CIA whistleblower who went to prison for releasing to a journalist the name of someone involved in the torture program, no American figure, not even those responsible for deaths at the Agency’s black sites, would be brought to court. And of course, the men (and woman) most responsible would leave the government to write their memoirs for millions of dollars and defend what they did to the death (of others).

It’s one for the history books and, though it’s a good thing to have the Senate report made public, it wasn’t needed to know that, in the years after 9/11, when the U.S. government created an offshore Bermuda Triangle of injustice, it also essentially became a criminal enterprise. Recently, Republican hawks in Washington protested loudly against the release of that Senate report, suggesting that it should be suppressed lest it “inflame” our enemies. The real question isn’t, however, about them at all, it’s about us. Why won’t the release of this report inflame Americans, given what their government has done in their names?

And in case you think it’s all over but for the shouting, think again, as Rebecca Gordon, TomDispatch regular and author of Mainstreaming Torture: Ethical Approaches in the Post-9/11 United States writes today. Tom Engelhardt

American torture — past, present, and… future?

Beyond the Senate torture report

By Rebecca GordonIt’s the political story of the week in Washington. At long last, after the endless stalling and foot-shuffling, the arguments about redaction and CIA computer hacking, the claims that its release might stoke others out there in the Muslim world to violence and “throw the C.I.A. to the wolves,” the report — you know which one — is out. Or at least, the redacted executive summary of it is available to be read and, as Senator Mark Udall said before its release, “When this report is declassified, people will abhor what they read. They’re gonna be disgusted. They’re gonna be appalled. They’re gonna be shocked at what we did.”

So now we can finally consider the partial release of the long-awaited report from the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence about the gruesome CIA interrogation methods used during the Bush administration’s “Global War on Terror.” But here’s one important thing to keep in mind: this report addresses only the past practices of a single agency. Its narrow focus encourages us to believe that, whatever the CIA may have once done, that whole sorry torture chapter is now behind us.

U.S. policies in the Arab world must be seen to resonate with its values

Nussaibah Younis writes: Secretary of state John Kerry tried to suppress publication of the CIA torture report, citing fears of a blowback against US targets in the Middle East. But the truth is that the region barely flinched in response to the publication of the 528-page document.

Almost all state-run media in the region ignored the report entirely, keen to play down their complicity in rendition programmes and their own rampant use of torture in domestic prisons. And the public in Arab countries took the revelations simply as confirmation of facts that they had long believed to be true. That the report has prompted such uproar in the US is comic to a region that expects dastardly behaviour from the US. If anything, many in the Arab world suspect that these admissions are just a small part of a much wider set of abuses yet to be exposed.

Despite the muted reaction, the revelations of the CIA’s extensive use of torture are extremely damaging to the US and to the west in general. The details are already being used as ammunition by Islamic State (Isis) to discredit the coalition intervention in Syria and Iraq, and will also severely undermine US efforts to prevent the use of torture in the Middle East.

The fact remains, however, that for those in the Middle East, the US lost its moral authority long before the publication of this report, largely because of its interventions in the Arab-Israeli conflict and its support of authoritarian governments. US partiality on the Israel-Palestine conflict has been shown to undercut its moral legitimacy in the region, with more than 80% of Jordanians, Moroccans, Saudis and Lebanese believing that the US has not been even-handed in its efforts to negotiate a solution.

Continued US support for repressive governments has also undermined confidence in the country. In September, President Obama gave a speech at the Clinton Global Initiative declaring: “Partnering and protecting civil society groups around the world is now a mission across the US government.” At the same time, his administration has fought to bypass pro-democracy conditions on military aid to Egypt, and last week achieved its goal by inserting a “national security” waiver into the spending bill expected to be passed by Congress soon. This is despite the fact that the government of President Abdel Fatah al-Sisi has mounted a fierce attack against civil society organisations in Egypt, forcing many of them to suspend their operations or leave the country. [Continue reading…]

Americans are deeply divided about torture

By Paul Gronke, Reed College; Darius Rejali, Reed College, and Peter Miller, University of Pennsylvania

The Senate report on torture found that the “enhanced techniques” used by the CIA were ineffective as a mechanism for gathering intelligence. In fact, the report stated there was no actionable intelligence gained while employing the controversial tactics used under the Detention and Interrogation Program that President Obama ended by Executive Order 13491 in January of 2009.

Will these findings, coupled with graphic explanations of the techniques, alter public opinion? Christopher Ingraham of the Washington Post warns us “not to kid ourselves: Most Americans are fine with torture, even when you call it ‘torture.“ Brittany Lyte of fivethirtyeight.com shows slightly more restraint while reporting “Americans have grown more supportive of torture.”

But have they? Public opinion polls have shown the contrary. The public has seldom been supportive of torture, even when presented with “ticking time bomb” scenarios where the intelligence is described as vital to stopping an impending terrorist attack. When asked about actual torture practices such as waterboarding or sexual humiliation, public support mostly collapses.

We have compiled the most exhaustive archive of US and international public opinion data on torture dating back to 2001. Additionally, we have conducted three survey experiments to identify the boundaries and probe the nuances of public attitudes about torture. The archive includes items asking about support for torture, support for specific torture techniques, and even some surveys of American military personnel.

Come clean on British links to CIA torture, MPs tell U.S. Senate

The Guardian reports: The head of the powerful Commons intelligence and security committee is demanding that the US hand over its archive of material documenting Britain’s role in the CIA’s abduction and torture programme developed in the wake of the 9/11 attack.

Sir Malcolm Rifkind, chair of the parliamentary inquiry into the complicity of British intelligence agencies in the US programme, has told the Observer that British MPs would seek the intelligence relating to the UK that was redacted from last week’s explosive Senate report, which concluded that the CIA repeatedly lied over its brutal but ineffective interrogation techniques.

The move comes amid escalating pressure on the government not to extend an agreement allowing the US to use the British Overseas Territory of Diego Garcia as a military base until its true role in the CIA’s extraordinary rendition has been established. [Continue reading…]

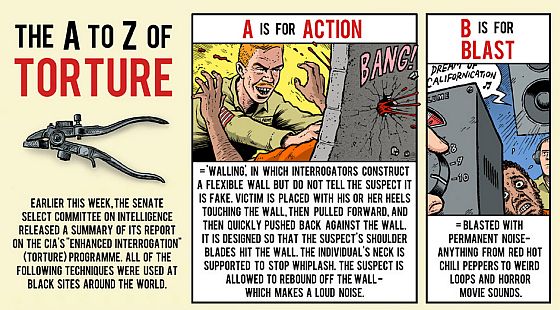

An illustrated A-to-Z of torture

Does torture work?

"Does torture work?" as a question needs to be put in the bin with "Is slavery commercially feasible?" & "Can genocide help overpopulation?"

— Hend (@LibyaLiberty) December 10, 2014

I interrogated the top terrorist in U.S. custody. Then the CIA came to town

Ali Soufan writes: In the middle of my interrogation of the high-ranking terrorist Abu Zubaydah at a black-site prison 12 years ago, my intelligence work wasn’t just cut short for so-called enhanced interrogation techniques to begin. After I left the black site, those who took over left, too – for 47 days. For personal time and to “confer with headquarters”.

For nearly the entire summer of 2002, Abu Zubaydah was kept in isolation. That was valuable lost time, and that doesn’t square with claims about the “ticking bomb scenarios” that were the basis for America’s enhanced interrogation program, or with the commitment to getting life-saving, actionable intelligence from valuable detainees. The techniques were justified by those who said Zubaydah “stopped all cooperation” around the time my fellow FBI agent and I left. If Zubaydah was in isolation the whole time, that’s not really a surprise.

One of the hardest things we struggled to make sense of, back then, was why US officials were authorizing harsh techniques when our interrogations were working and their harsh techniques weren’t. The answer, as the long-awaited Senate Intelligence Committee report now makes clear, is that the architects of the program were taking credit for our success, from the unmasking of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed as the mastermind of 9/11 to the uncovering of the “dirty bomber” Jose Padilla. The claims made by government officials for years about the efficacy of “enhanced interrogation”, in secret memos and in public, are false. “Enhanced interrogation” doesn’t work. [Continue reading…]

U.S. hid U.K. links in CIA torture report at request of British spy agencies

The Guardian reports: References to Britain’s intelligence agencies were deleted at their request from the damning US report on the CIA’s use of torture after 9/11, it has emerged.

A spokesman for David Cameron acknowledged the UK had been granted deletions in advance of the publication, contrasting with earlier assertions by No 10. Downing Street said any redactions were only requested on “national security” grounds and contained nothing to suggest UK agencies had participated in torture or rendition.

However, the admission will fuel suspicions that the report – while heavily critical of the CIA – was effectively sanitised to conceal the way in which close allies of the US became involved in the global kidnap and torture programme that was mounted after the al-Qaida attacks.

On Wednesday, the day the report was published, asked whether redactions had been sought, Cameron’s official spokesman told reporters there had been “none whatsoever, to my knowledge”.

However, on Thursday, the prime minister’s deputy official spokesman said: “My understanding is that no redactions were sought to remove any suggestion that there was UK involvement in any alleged torture or rendition. But I think there was a conversation with the agencies and their US counterparts on the executive summary. Any redactions sought there would have been on national security grounds in the way we might have done with any other report.” [Continue reading…]

CIA director refuses to acknowledge agency engaged in torture

Foreign Policy reports: At an unusual news conference at the CIA’s headquarters in Langley, Virginia, spy chief John Brennan disavowed the agency’s former system for detaining and brutally interrogating terror suspects in the immediate aftermath of the 9/11 attacks and said some of the methods used were “abhorrent,” but he refused to join President Barack Obama in admitting that they had crossed the line into “torture.”

Asked repeatedly whether waterboarding suspects or threatening them with mock executions led to actionable intelligence, Brennan insisted that the agency couldn’t conclusively say that harsh interrogations produced information that could otherwise not have been obtained.

“The cause-and-effect relationship between the application of those EITs [enhanced interrogation techniques] and ultimate provision of that information” from detainees “is unknown and unknowable,” Brennan said in response to a question. “But for someone to say that there was no intelligence of value, of use, that came from those detainees once they were subjected to EITs, I think that lacks any foundation at all.” [Continue reading…]

Details of how U.S. rebuked foreign regimes while using same torture methods

James Ross writes: So the CIA doesn’t consider “waterboarding” — mock execution by near drowning — to be torture, but the U.S. State Department does.

State Department reports from 2003 to 2007 concluded that Sri Lanka’s use of “near-drowning” of detainees was among “methods of torture.” Its reports on Tunisia from 1996 to 2004 classified “submersion of the head in water” as “torture.” In fact, the U.S. military has prosecuted variants of waterboarding for more than 100 years — going back to the U.S. occupation of the Philippines in the early 1900s.

If you want to know whether the U.S. government considers the “enhanced interrogation techniques” described in the Senate Intelligence Committee’s report summary on the CIA’s interrogation program to be torture, you could read President Barack Obama’s 2009 statement rejecting the use of waterboarding — or you could click on the State Department’s annual Country Reports on human rights conditions. It turns out that all those methods carried out by the CIA would be torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment if committed by other governments.

The grotesque and previously unreported “anal feeding” and “anal rehydration” discussed in the Senate report may not have been used elsewhere, but the State Department has reported on analogous sexual assault of prisoners as a form of torture. Its 2012 report on Syria described as custodial torture the “forcing of objects into the rectum.”

Stress positions and forced standing also can amount to torture. The State Department’s 2006 report on Jordan said that subjecting detainees to “forced standing in painful positions for prolonged periods” was torture. It also described as torture the Iranian practice of “suspension for long periods in contorted positions.”

The same holds true for sleep deprivation and blaring music. In State Department reports on Indonesia, Iran, Jordan, Libya, and Saudi Arabia, sleep deprivation was classified as torture. The 2002 report on Turkey lists “loud music” as a torture method. [Continue reading…]

Bush and Cheney must have known about the CIA’s use of torture

Fred Kaplan writes: Of all the shocks and revelations in the Senate Intelligence Committee’s report on CIA torture, one seems very strange and unlikely: that the agency misinformed the White House and didn’t even brief President George W. Bush about its controversial program until April 2006.

The question of the claim’s truth or implausibility is not trivial or academic; it goes well beyond score-settling, Bush-bashing, or scapegoating. Rather, it speaks to an issue that’s central in the report in the long history of CIA scandals, and in debates over whether and how policy should be changed: Did the torture begin, and did it get out of hand, because the CIA’s detention and interrogation program devolved into a rogue operation? Or were the program’s managers actually doing the president’s dirty business?

If the former was the case, then heads should roll, grand juries should be assembled, organizational charts should be reshuffled, and mechanisms of oversight should be tightened. If the latter was the case, well, that’s what elections are for. “Enhanced-interrogation techniques” were formally ended by President Obama after the 2008 election, and perhaps future presidents will read the report with an eye toward avoiding the mistakes of the past.

But which was it? Were the CIA’s directorate of operations and its counterterrorism center freelancing after the Sept. 11 attacks, or were they exchanging winks and nods with the commander-in-chief?

The annals of history suggest the latter, and in a few passages, so does the report. [Continue reading…]

American identity, torture and the game of political indignation

Adversarial Journalism™ is a gimmick that far from serving as an agent of change, functions much more as an opiate of the people, sustaining the status quo.

Whenever politics is reduced to us and them, it goes without saying that the problem is them.

And when this polarity is between a powerful political establishment and weak but loud voices of dissent, dissent becomes inclined to follow the path of least resistance. The path of least resistance is one that leads nowhere because it predicts that change is impossible.

Those taking a stand against imperial power do so while insisting it is deaf to its critics.

Thus the master du jour of adversarial journalism, Glenn Greenwald, wrote this in response to the release of the Senate torture report:

Any decent person, by definition, would react with revulsion to today’s report, but nobody should react with confidence that its release will help prevent future occurrences by a national security state that resides far beyond democratic accountability, let alone the law.

Even though there is some truth to this conclusion it nevertheless employs a polemical deceit which is to implicitly absolve America culturally and nationally for the use of torture and locates them — the bad guys — all inside the national security state.

Ironically, this is the same strategy for damage control so often used inside government: avoid facing systemic problems by focusing attention on a few bad apples.

In American adversarial journalism, America’s bad apple is Washington.

In an interview in Salon today, Elias Isquith asks Greenwald whether he sees in the torture story, the story of “a society-wide failure,” but Greenwald frames his response in terms of the culpability of the political and media establishment and a society that has passively become desensitized. Rather than see society-wide failure, he seems to prefer to cast American society as another victim — a view that supports the us vs. them mentality of his American audience, which has a strong preference for railing against Power rather than looking in the mirror.

Dissent which opposes and yet never proposes is ultimately a game that justifies apathy and cynicism. It presents a picture of a rotten world in which our power extends no further than our ability to occasionally express our outrage.

But there is an alternative.

The starting point here is to acknowledge that the torture story is not just a story about the CIA, or the national security state, or Washington, or the media establishment, or post-9/11 America, but rather it is a story about America itself, its people and its history.

Those who remain stuck in the deeply worn tracks of political discourse are not so inclined to speak and think in such broad terms because once you start looking through the prisms of culture, history, and psychology, politics itself loses much of its dramatic significance.

The wide-angle view to which I allude is uncommon but thankfully I just stumbled across an example from Philip Kennicott.

During the thirteen years that I have been running this site, some of the most interesting and insightful commentaries I have highlighted came from Kennicott, the Art and Architecture Critic for the Washington Post.

His interest in form, its construction and its effect, naturally translates into a consideration of the contours of American identity in light and shadow.

Kennicott writes:

Our belief in the national image is astonishingly resilient. Over more than two centuries, our conviction that we are a benign people, with only the best of intentions, has absorbed the blows of darker truths, and returned unassailable. We have assimilated the facts of slavery and ethnic cleansing of Native Americans, and we are still a good people; we became an empire, but an entirely benevolent one; we bombed Southeast Asia on a scale without precedent, but it had to be done, because we are a good people.

Even the atrocities of Abu Ghraib have been neutralized in our conscience by the overwhelming conviction that the national image transcends the particulars of a few exceptional cases. And now the Senate torture report has made the unimaginable entirely too imaginable, documenting murder, torture, physical and sexual abuse, and lies, none of them isolated crimes, but systematic policy, endorsed at the highest levels, and still defended by many who approved and committed them.

Again, it has become a conversation about the national image, this phoenix of self-deception that magically transforms conversations about what we have done into debates about what we look like. The report, claimed headlines, “painted a picture of an agency out of control,” and “portrays a broken CIA devoted to a failed approach.” The blow to the U.S. reputation abroad was seen as equally newsworthy as the details themselves, and the appalling possibility that there will never be any accountability for having broken our own laws, international law and the fundamental laws of human decency.

He concludes by saying: “we must learn that the national image is a hollow conceit. What we desperately need is a national conscience.”

For America to re-envision itself, for it to shed its vanity, maybe this doesn’t just require questioning how America defines itself but also who defines what it means to be American.

There are millions of Americans who (like me) are not Americans.

The process of so-called naturalization, even though it involves a ceremonial rebirth — acquiring citizenship and making the pledge of allegiance get staged like a religious conversion — doesn’t erase history.

Every American who grew up somewhere else, knows another culture and knows what America looks like from the outside.

America welcomes its immigrants, calls itself a nation of immigrants and yet those who were not born here are somehow not fully qualified to say what it means to be an American. The naturalization process can only ever be partially successful. We inevitably remain sullied by some impurities and the Constitution ensures that the sanctum sanctorum of American identity, the White House, will never be tainted by an occupant born on foreign soil.

America’s self-aggrandizing tendencies, it’s need to see itself as exceptional, what to the outsider can often look like simple arrogance, seems to me more like a relentless self-affirmation driven by an unspoken insecurity.

The myth of America’s greatness needs to be perpetually propped up as though if it was not pronounced often enough and not enough flags were flown, the image would swiftly collapse. America’s grandiosity is not matched by self-assurance. What other country is there whose leaders and citizens expend as much energy telling each other and themselves about the greatness of their nation?

This sense that America can only be sustained by its own self-worship, speaks to the fact that a society made up of people who virtually all came from somewhere else — directly or indirectly — has a national identity held together by weak glue.

Still, America’s disparate roots are in fact its greatest strength and its identity problem stems from a struggle to be what it is not while denying its real nature.

Those Americans who became torturers, thought they were defending America, and yet what they were really clinging onto was an identity that constructed an unbridgeable gulf between American and foreign. The only thing about which they had no doubt was that their victims were not American.

For Americans to stop dehumanizing others, they need to start embracing their own otherness.

CIA ‘torture’ practices started long before 9/11 attacks

Jeff Stein reports: “The CIA,” according to the Senate Intelligence Committee, had “historical experience using coercive forms of interrogation.” Indeed, it had plenty, said the committee’s report released Tuesday: about 50 years’ worth. Deep in the committee’s 500-page summary of a still-classified 6,700-page report on the agency’s use of “enhanced interrogation techniques” after 9/11 there is a brief reference to KUBARK, the code name for a 1963 instruction manual on interrogation, which was used on subjects ranging from suspected Soviet double agents to Latin American dissidents and guerrillas.

The techniques will sound familiar to anybody who has followed the raging debate over interrogation techniques adopted by the CIA to break Al-Qaeda suspects in secret prisons around the world. When the going got tough, the CIA got rough.

The 1963 KUBARK manual included the “principal coercive techniques of interrogation: arrest, detention, deprivation of sensory stimuli through solitary confinement or similar methods, threats and fear, debility, pain, heightened suggestibility and hypnosis, narcosis and induced regression,” the committee wrote. [Continue reading…]

The victims of CIA torture

Noa Yachot from the ACLU writes: This International Human Rights Day – as we consider how we went so dramatically off course, and how we can make amends – let’s especially remember the victims and survivors of the U.S. torture program. They haven’t found recourse in U.S. courts, and they weren’t interviewed for the Senate report. Some remain detained without charge or trial, and many are still coping with the deep psychological scars and physical consequences of torture. But their stories can still be told, and the Senate report goes into laudable detail on what they endured.

Four such stories, based almost exclusively on information taken from the Senate torture report, are shared below. They don’t include the detainees forced to stand on broken legs, endure ice water baths, or undergo “rectal rehydration” (in reality, rape) at the hands of interrogators, at least one of whom had anger management issues while another “reportedly admitted to sexual assault.” These stories represent just a fraction of the prisoners profiled in the report, including at least 26 individuals wrongfully detained even according to the CIA’s unlawful standards.

But together, they represent many of the worst elements of the program – the abuse itself, the breakdown in oversight, the preference for merciless brutality over credible intelligence gathering, and the complicity of the highest levels of government. [Continue reading…]

The psychologists who taught the CIA how to torture (and charged $180 million)

Katherine Eban writes: I was the first reporter to enumerate the roles of the two key psychologists, James Elmer Mitchell and Bruce Jessen, as architects of the coercive interrogation tactics, in a 2007 story in Vanity Fair. The pair had previously been Air Force trainers in a program called SERE (Survival Evasion Resistance Escape), which subjected military members to mock interrogations—interrogations that ironically had been used by the Communist Chinese against American servicemen during the Korean war in order to produce false confessions.

Historically, the C.I.A. knew the tactics would not be useful. In 1989, the C.I.A. informed Congress that “inhumane physical or psychological techniques are counterproductive because they do not produce intelligence and will probably result in false answers.” In the desperate months after 9/11, the C.I.A. willfully ignored its own findings.

The agency threw in its lot with Mitchell and Jessen, who are identified in the report by the pseudonyms Swigert and Dunbar. As the report notes, “Neither psychologist had any experience as an interrogator, nor did either have specialized knowledge of al-Qa’ida, a background in counterterrorism, or any relevant cultural or linguistic expertise.” Nonetheless, the psychologists played a role in convincing the administration that if they were allowed to reverse engineer the SERE tactics, they could break down detainees, resulting in useful intelligence.

With no previous evidence of success, they were given the greenlight to use the training techniques on actual detainees. The F.B.I. had used rapport-building techniques to extract vital intelligence from Abu Zubaydah, one of the first detainees in our war on terror. From a hospital bed in Thailand, he disclosed to F.B.I. interrogators that Khalid Shaikh Mohammed was actually the mastermind behind the 9/11 attacks.

But subsequently, Mitchell showed up in Thailand, and began to oversee the work of breaking down Zubaydah: keeping him in a coffin-shaped box, blasting music at him, locking him in a freezing room. The C.I.A. falsely claimed credit for the intelligence he provided, and, ultimately, the use of the tactics spread like wildfire through C.I.A. and military interrogation sites. In short, Mitchell and Jessen sold the C.I.A. an argument it wanted to hear: namely, that the use of coercive interrogation techniques would produce groundbreaking intelligence and thereby prevent another attack. It was well known within the SERE community that the use of such techniques was better designed to produce false information. There was seemingly no legitimate argument for its utility. [Continue reading…]

This disaster happened because the CIA outsourced accountability

Patrick M. Skinner writes: As a former CIA case officer, it’s particularly maddening to read the report. Throughout the Senate Intelligence Committee’s report on the CIA’s detention and interrogation program, the reader can see where CIA Headquarters overruled the assessments of its own staff personnel that were at the various “black sites,” conducting—or, more often, witnessing—interrogations done by contractors. At numerous times throughout the interrogations of Abu Zubayda, Abd al-Rahman al-Nashiri, and Ramzi bin al-Shibh, agency officers communicated back to headquarters their assessment that the subject was cooperating or had no more information of value that warranted additional pressure. And virtually every time, headquarters came back with a more definitive assessment that they knew the subject was withholding more vital information.

Where did this certainty come from?

Part of the answer is that it wasn’t CIA personnel actually running the program, even if they were ultimately responsible for it. As noted in the Senate report, the overwhelming majority (80%) of the people directly involved in the disastrous program were contractors, with the initial and primary responsibility resting on two contractors who had zero relevant experience, as well as those in the Agency who vouched for them. While the most shameful details of the report involve the indefensible tactics, another shame is that the Agency — at great effort and expense — hired and trained some of the most capable people in the country to collect needed intelligence; and after the worst terrorist attack in our nation’s history, the agency outsourced one of its most important tasks.

Of course, no CIA personnel had the “relevant experience” in running detention programs because the agency wasn’t, and shouldn’t be, in that business. Once the decision was made for indefinite detention and interrogation, the agency decided to contract out this new mission to people who had even less experience, but who weren’t as bound to the agency code of ethics. This doesn’t excuse the agency from what happened; it actually makes it much more inexcusable, even allowing for the understandable fear and chaos after 9/11. [Continue reading…]

Globalized torture and American values

What’s wrong with torture?

That might sound like a question that doesn’t need asking, yet given that there are so many answers circulating right now, it’s worth treating this as a question whose answer is not obvious. Moreover, the question needs to be broken down since we need to examine its two components: wrong and torture.

In their public statements, Bush administration officials always tried to duck the issue by claiming that their use of “enhanced interrogation techniques” did not involve torture. The spineless American press corps was complicit in facilitating this PR maneuver by also refraining from using the term torture.

But even while the administration denied approving the use of torture, it simultaneously developed a legal defense on the basis that torture might be a necessity for saving lives.

Despite the fact that for years, American journalists acted like dummies incapable of labeling something as torture unless given permission to do so by the political establishment, there was never much real debate inside the administration about whether its interrogation practices involved torture. The only question was whether they could use torture without risking prosecution.

The so-called “necessity defense” was one that attempted to absolve torturers of moral and legal responsibility for their actions by claiming that they had no choice — that they needed to torture in order to “save lives.”

As soon as the question gets raised — does torture work? in the sense that it might yield life-saving intelligence — the question of the morality of torture has been muddied.

The implication is that if torture could be shown to work, then even if it might be deemed wrong it is nevertheless justifiable because the wrong serves a greater good.

In this regard, many among the American Right — which otherwise postures as the stronghold of moral absolutists — turn out to be moral relativists.

The bipartisan argument against torture is one rooted in nationalism posturing as morality. Thus in her introduction, Senate Select Committee on Intelligence Chairman Dianne Feinstein, writes:

The major lesson of this report is that regardless of the pressures and the need to act, the Intelligence Community’s actions must always reflect who we are as a nation, and adhere to our laws and standards. It is precisely at these times of national crisis that our government must be guided by the lessons of our history and subject decisions to internal and external review.

Instead, CIA personnel, aided by two outside contractors, decided to initiate a program of indefinite secret detention and the use of brutal interrogation techniques in violation of US. law, treaty obligations, and our values.

In its use of torture, the CIA failed to “reflect who we are as a nation,” and it betrayed “our values.”

Torture is wrong — supposedly — because it is un-American.

Ironically, one of the distinguishing features of American values is that they are frequently cited yet rarely articulated.

This habit of invoking American values without spelling out what they are, indicates that to a significant degree, American values are not so much values as they are a form of national vanity.

To offer, “because we are American,” as an explanation for anything is to offer no explanation at all but rather to assert that there is some special virtue in being American.

No doubt, all those who now assert that the use of torture conflicts with our values would say that those values dictate that prisoners should be treated humanely.

Yet to suggest that humane treatment is in some sense a distinctively American virtue implies that it cannot be expected to prevail elsewhere.

Given the lack of human rights across much of the world, there is indeed some commonsense truth to this assumption — but there is also a contradiction.

The contradiction is this: a sense of what is humane rests on a sense of humanity, which is that on a fundamental level human beings are all endowed with the same capacities, and yet if there is a distinct virtue in being American, then supposedly Americans are in an important way different from everyone else.

If America must abstain from torture because it conflicts with America’s self-image, does a non-torturing America assume that torture will continue elsewhere — business as usual in a world that can’t be expected to live up to American values?

Even while the Bush administration refused to acknowledge that it had institutionalized torture, according to an Open Society report published in 2013, it nevertheless managed to win the cooperation of 54 countries in the following ways:

[B]y hosting CIA prisons on their territories; detaining, interrogating, torturing, and abusing individuals; assisting in the capture and transport of detainees; permitting the use of domestic airspace and airports for secret flights transporting detainees; providing intelligence leading to the secret detention and extraordinary rendition of individuals; and interrogating individuals who were secretly being held in the custody of other governments. Foreign governments also failed to protect detainees from secret detention and extraordinary rendition on their territories and to conduct effective investigations into agencies and officials who participated in these operations.

Those countries were:

Afghanistan, Albania, Algeria, Australia, Austria, Azerbaijan, Belgium, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Canada, Croatia, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Djibouti, Egypt, Ethiopia, Finland, Gambia, Georgia, Germany, Greece, Hong Kong, Iceland, Indonesia, Iran, Ireland, Italy, Jordan, Kenya, Libya, Lithuania, Macedonia, Malawi, Malaysia, Mauritania, Morocco, Pakistan, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, South Africa, Spain, Sri Lanka, Sweden, Syria, Thailand, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, United Kingdom, Uzbekistan, Yemen, and Zimbabwe.

That the U.S. could find so many willing partners is clearly a reflection of American power and the fears that many governments justifiably harbor about being penalized if they were to resist American pressure.

But this also says a lot about prevailing attitudes towards torture. It’s use is always seen as expedient (or inexpedient) and the harm it does tends to be measured more in terms of how it will politically harm the perpetrators rather than the actual victims.

A few months ago, Congress received another report on torture, but this one gained only a fraction of the media and public attention that is being given to the current report.

That lack of attention followed from the fact that neither the torturers nor their victims were American — they were Syrian.

In July, the Daily Beast reported:

The regime of Syrian President Bashar al Assad is holding 150,000 civilians in custody, all of whom are at risk of being tortured or killed by the state, the Syrian defector known as “Caesar” told Congress on Thursday.

According to a senior State Department official, his department initially asked to keep this hearing — in which Caesar displayed new photos from his trove of 55,000 images showing the torture, starvation, and death of over 11,000 civilians — closed to the public, out of concerns for the safety of the defector and his family. Caesar smuggled the pictures out of Syria when he fled last year in fear for his life. Caesar’s trip had been in the works for months.

There was no audio or video recording allowed at the hearing; the House Foreign Affairs Committee said that decision was made in consideration of Caesar’s safety. He sat at the witness table disguised in a baseball cap and sunglasses, with a blue hoodie over his head. “We recommended to Congress a format for today’s briefing that would have allowed press access while addressing any security concerns,” said Edgar Vasquez, a State Department spokesman. A committee staffer alleged State had tried to prevent the hearing from happening at all.

The packed committee room sat in silent horror as new examples of Assad’s atrocities were splashed on the large television screens on the wall and displayed on large posterboards littered throughout the hearing room. Caesar spoke softly to his translator, Mouaz Moustafa, the executive director of the Syrian American Task Force, a Washington-based organization that works with both the Syrian opposition and the U.S. State Department.

“I am not a politician and I don’t like politics,” Caesar said through his translator. “I have come to you honorable Congress to give you a message from the people of Syria… What is going on in Syria is a genocidal massacre that is being led by the worst of all the terrorists, Bashar al Assad.”

The international community must do something now or the 150,000 civilians still held in regime custody could meet the same bleak fate, Caesar said. America had been known as a country that protected civilians from atrocities, he argued, referring to past humanitarian crises such as ethnic cleansing in Yugoslavia.

Following the release of the Senate report on torture, President Obama said: “I hope that today’s report can help us leave these techniques where they belong — in the past.”

Move on, don’t look back, and ignore the rest of the world — these are the prevailing American values and they express no guiding morality, but instead an abiding indulgence in ignorance.