David Wearing writes: The Centre for Labour and Social Studies (CLASS) has just published a free-to-download, short presentation of the key findings from Kate Pickett and Richard Wilkinson’s hugely successful book “The Spirit Level”. The pamphlet, entitled “Why Inequality Matters“, also includes a set of proposed measures to decrease the wage gap, reform the tax system, and develop public services. Its aim is to empower and enable a collective effort to push the issue of inequality into the centre of political debate.

Britain, alongside the US, is one of the most unequal countries in the developed world, and as Pickett and Wilkinson showed in The Spirit Level, high levels of inequality are connected to a wide range of social ills, from poor physical and mental health to violent crime and drug abuse. The counter-assertion made by right-wing liberals that equality of opportunity is more important than equality of outcome is shown to be a false dichotomy. Social mobility is actually lowest in the most unequal countries. If you want the American dream, move to Sweden.

It is worth noting that the theory underpinning these findings is essentially drawn from the observation that human beings are deeply social animals, acutely responsive to how they relate to the rest of society. The sense of alienation caused by living in an unequal society is the source of huge anxiety, and debilitating effects on people’s sense of self, which in turn leads to some of the symptoms highlighted above. The detailed explanation of how this works presented in The Spirit Level is extremely illuminating, and I strongly recommend the original book to anyone who has yet to read it.

Category Archives: inequality

Still separate and unequal

Rhena Catherine Jasey writes: Legal segregation is no more in the United States, but the de facto segregation of far too many American schools and whole school districts continues to this day. And yes, educational outcomes depend on more than what happens in schools, but nonetheless, the struggle for equity and fairness in public education is the preeminent civil rights issue of our time.

We face a basic question of justice and equity when it comes to the first building blocks of the educational process. The most vulnerable members of our society, children in our neediest areas, face a gross injustice when they go to school each day. The Campaign for Educational Equity, which is now studying New York City public schools, has identified several gaps in “availability of basic educational resources.” (These resources are those listed by Justice Leland DeGrasse in the Campaign for Fiscal Equity v. State of New York court case as necessary in order to “provide all students the opportunity for a sound basic education under the New York State Constitution.”) The Campaign’s research confirms what I have seen firsthand. The schools serving our poor urban populations face a chronic and pervasive lack of resources to support teacher development, to provide a safe learning environment for children, to support curriculum development and to provide basic technology. These problems are not isolated, but systemic.

Given all the variables at work in education, it is a real challenge to guarantee equal educational outcomes, and yet we must insist on a level playing field for all our children regardless of the circumstances of their birth. The fact is that many of our urban students require more support to have a fair opportunity to excel academically, and it is their basic civil right to expect that level of investment from society.

It is disappointing and surprising that so many people seem blind to the current state of affairs in public education. Many deny that the inequalities that exist between the children of middle and upper-middle class parents and their poorer counterparts is an issue of justice. Some claim that the issue is “cultural”, a capacious word used in this case to mean “futile.” Whatever the silent assumptions lurking in the background, the fact is that few not already engaged in addressing the problem feel much motivation to do anything about it. There is certainly no sense of urgency among the general public, or in our political class as a whole, about addressing the current state of public education in our cities.

It is instructive to compare this widespread apathy with the dramatic activism that in past decades overcame other societal injustices. We have seen, for example, remarkable shifts in public opinion, and in the application of our concepts of justice and equity, with respect to the handicapped. Our society and government have also reacted vigorously to the perils of second-hand smoke. We have come a long way in a short time, and spent billions and passed many laws, when it came to creating and enforcing new behavioral norms to protect the environment. The sense of the public welfare has been so strong in these areas that the public will has developed to pursue initiatives that benefit society notwithstanding the fact that the benefits may not correlate with the population making the bulk of the sacrifice. What has applied in those cases applies as much as, if not more, to the task of providing a more equitable educational experience for poor urban and rural children: Everyone would gain. This is not charity but self-interested social investment. How do we explain the lack of public ardor for fixing our educational inequalities? [Continue reading…]

Why the super-rich threaten America

Mike Lofgren writes: It was 1993, during congressional debate over the North American Free Trade Agreement. I was having lunch with a staffer for one of the rare Republican congressmen who opposed the policy of so-called free trade. To this day, I remember something my colleague said: “The rich elites of this country have far more in common with their counterparts in London, Paris, and Tokyo than with their fellow American citizens.”

That was only the beginning of the period when the realities of outsourced manufacturing, financialization of the economy, and growing income disparity started to seep into the public consciousness, so at the time it seemed like a striking and novel statement.

At the end of the Cold War many writers predicted the decline of the traditional nation-state. Some looked at the demise of the Soviet Union and foresaw the territorial state breaking up into statelets of different ethnic, religious, or economic compositions. This happened in the Balkans, the former Czechoslovakia, and Sudan. Others predicted a weakening of the state due to the rise of Fourth Generation warfare and the inability of national armies to adapt to it. The quagmires of Iraq and Afghanistan lend credence to that theory. There have been numerous books about globalization and how it would eliminate borders. But I am unaware of a well-developed theory from that time about how the super-rich and the corporations they run would secede from the nation state.

I do not mean secession by physical withdrawal from the territory of the state, although that happens from time to time—for example, Erik Prince, who was born into a fortune, is related to the even bigger Amway fortune, and made yet another fortune as CEO of the mercenary-for-hire firm Blackwater, moved his company (renamed Xe) to the United Arab Emirates in 2011. What I mean by secession is a withdrawal into enclaves, an internal immigration, whereby the rich disconnect themselves from the civic life of the nation and from any concern about its well being except as a place to extract loot.

Our plutocracy now lives like the British in colonial India: in the place and ruling it, but not of it. If one can afford private security, public safety is of no concern; if one owns a Gulfstream jet, crumbling bridges cause less apprehension—and viable public transportation doesn’t even show up on the radar screen. With private doctors on call and a chartered plane to get to the Mayo Clinic, why worry about Medicare? [Continue reading…]

Eight ways America’s headed back to the robber-baron era

Erik Loomis writes: Over the past 40 years, corporations and politicians have rolled back many of the gains made by working and middle-class people over the previous century. We have the highest level of income inequality in 90 years, both private and public sector unions are under a concerted attack, and federal and state governments intend to cut deficits by slashing services to the poor.

We are recreating the Gilded Age, the period of the late 19th and early 20th centuries when corporations ruled this nation, buying politicians, using violence against unions, and engaging in open corruption. During the Gilded Age, many Americans lived in stark poverty, in crowded tenement housing, without safe workplaces, and lacked any safety net to help lift them out of hard times.

With Republicans more committed than ever to repealing every economic gain the working-class has achieved in the last century and the Democrats seemingly unable to resist, we need to understand the Gilded Age to see what conservatives are trying to do to this nation. Here are 8 ways our corporations, politicians and courts are trying to recreate the Gilded Age. [Continue reading…]

The sharp, sudden decline of America’s middle class

Jeff Tietz writes: Every night around nine, Janis Adkins falls asleep in the back of her Toyota Sienna van in a church parking lot at the edge of Santa Barbara, California. On the van’s roof is a black Yakima SpaceBooster, full of previous-life belongings like a snorkel and fins and camping gear. Adkins, who is 56 years old, parks the van at the lot’s remotest corner, aligning its side with a row of dense, shading avocado trees. The trees provide privacy, but they are also useful because she can pick their fallen fruit, and she doesn’t always have enough to eat. Despite a continuous, two-year job search, she remains without dependable work. She says she doesn’t need to eat much – if she gets a decent hot meal in the morning, she can get by for the rest of the day on a piece of fruit or bulk-purchased almonds – but food stamps supply only a fraction of her nutritional needs, so foraging opportunities are welcome.

Prior to the Great Recession, Adkins owned and ran a successful plant nursery in Moab, Utah. At its peak, it was grossing $300,000 a year. She had never before been unemployed – she’d worked for 40 years, through three major recessions. During her first year of unemployment, in 2010, she wrote three or four cover letters a day, five days a week. Now, to keep her mind occupied when she’s not looking for work or doing odd jobs, she volunteers at an animal shelter called the Santa Barbara Wildlife Care Network. (“I always ask for the most physically hard jobs just to get out my frustration,” she says.) She has permission to pick fruit directly from the branches of the shelter’s orange and avocado trees. Another benefit is that when she scrambles eggs to hand-feed wounded seabirds, she can surreptitiously make a dish for herself.

By the time Adkins goes to bed – early, because she has to get up soon after sunrise, before parishioners or church employees arrive – the four other people who overnight in the lot have usually settled in: a single mother who lives in a van with her two teenage children and keeps assiduously to herself, and a wrathful, mentally unstable woman in an old Mercedes sedan whom Adkins avoids. By mutual unspoken agreement, the three women park in the same spots every night, keeping a minimum distance from each other. When you live in your car in a parking lot, you value any reliable area of enclosing stillness. “You get very territorial,” Adkins says.

Each evening, 150 people in 113 vehicles spend the night in 23 parking lots in Santa Barbara. The lots are part of Safe Parking, a program that offers overnight permits to people living in their vehicles. The nonprofit that runs the program, New Beginnings Counseling Center, requires participants to have a valid driver’s license and current registration and insurance. The number of vehicles per lot ranges from one to 15, and lot hours are generally from 7 p.m. to 7 a.m. Fraternization among those who sleep in the lots is implicitly discouraged – the fainter the program’s presence, the less likely it will provoke complaints from neighboring homes and churches and businesses.

The Safe Parking program is not the product of a benevolent government. Santa Barbara’s mild climate and sheltered beachfront have long attracted the homeless, and the city has sometimes responded with punitive measures. (An appeals court compared one city ordinance forbidding overnight RV parking to anti-Okie laws in the 1930s.) To aid Santa Barbara’s large homeless population, local activists launched the Safe Parking program in 2003. But since the Great Recession began, the number of lots and participants in the program has doubled. By 2009, formerly middle-class people like Janis Adkins had begun turning up – teachers and computer repairmen and yoga instructors seeking refuge in the city’s parking lots. Safe-parking programs in other cities have experienced a similar influx of middle-class exiles, and their numbers are not expected to decrease anytime soon. It can take years for unemployed workers from the middle class to burn through their resources – savings, credit, salable belongings, home equity, loans from family and friends. Some 5.4 million Americans have been without work for at least six months, and an estimated 750,000 of them are completely broke or heading inexorably toward destitution. In California, where unemployment remains at 11 percent, middle-class refugees like Janis Adkins are only the earliest arrivals. “She’s the tip of the iceberg,” says Nancy Kapp, the coordinator of the Safe Parking program. “There are many people out there who haven’t hit bottom yet, but they’re on their way – they’re on their way.” [Continue reading…]

Class decides everything

Richard Florida writes: Class has long been a dirty word in America. We’re the society of opportunity after all – the place where anyone from anywhere can aspire to be president or at least get very rich. Innumerable pundits and a litany of books have trumpeted the eclipse of class and the rise of a classless society. It’s an old saw. Way back in the late 1950s, the sociologist Robert Nisbet declared, “the term social class … is nearly valueless for the clarification of data on wealth power and status.”

But numerous indicators and metrics suggest that class does structure a great deal of American life. America lags behind many nations – from Denmark to the United Kingdom and Canada – in the ability of its people to achieve significant upward mobility. America’s jobs crisis bears the unmistakable stamp of class. This past spring, for example, the rate of unemployment for people who did not graduate from high school was 13 percent, substantially more than the overall rate of 8.2 percent and more than three times the 3.9 percent rate for college grads. At a time when the unemployment rate for production workers who contribute their physical labor was more than 10 percent, unemployment for professionals, techies and managers who work with their minds had barely broken 4 percent.

While the political left has long pointed to America’s social and economic divides, a number of influential commentators on the right have only recently been drawn to the issue. “America is being polarized by class divisions that didn’t exist a quarter century ago,” writes Charles Murray in his book “Coming Apart.” “We have developed a new upper class with advanced educations, often obtained at elite schools, sharing tastes and preferences that set them apart from mainstream America. At the same time, we have developed a new lower class, characterized not by poverty but by withdrawal from America’s core cultural institutions.” While many have criticized the cultural and sociological underpinnings and implications of Murray’s argument, there’s no getting around the fact that he accurately identifies class as a, if not the, central axis of contemporary American life.

My own research bears this out. My initial research over a decade ago identified the rise of the creative class as a key factor in America’s cities and economy overall. What has struck me since is that the effects of class are not just limited to cities, jobs and the economy. Class increasingly structures virtually every aspect of our society, culture and daily lives — from our politics and religion to where we live and how we get to work, from the kind of education we can provide for our children to our very health and happiness. [Continue reading…]

Major new campaign for a ‘Robin Hood tax’ launches today

Dozens of national organizations including National Nurses United and Health GAP, celebrities including Mark Ruffalo, Rage Against the Machine’s Tom Morello and Coldplay’s Chris Martin, leading economists including Jeffrey Sachs, former JP Morgan and Goldman Sachs executives and global leaders such as Desmond Tutu joined today for an unprecedented coalition, calling for a “Robin Hood Tax” on Wall Street.

The Robin Hood Tax is a small sales tax, less than half of 1% — or 50 cents per $100 on trading in stocks, and even smaller assessments on bonds, derivatives and currencies, that could raise hundreds of billions in the U.S.

“Wall Street’s reckless speculation and risky deals caused our economy’s most devastating crash since the Great Depression, forcing millions of Americans to lose their jobs, their homes, and their pensions,” said Jean Ross, RN and co-president of NNU. “Three years later, Americans on Main Street still struggle to recover from a crisis we didn’t create. This is the way to start to turn it around.”

Stephen Frum, RN, a nurse at Washington Hospital Center, added, “As registered nurses in D.C., we see so much suffering related to the economic crisis. Our patients and our own families often struggle to make ends meet and our health suffers. The Robin Hood Tax is something we can all get behind, and nurses will lead the charge.”

Mark Ruffalo, star of the current movie “The Avengers,” releases a video on Tuesday calling on Americans to join the campaign. He was joined in the video by Chris Martin and Tom Morello.

The Robin Hood Tax is aimed at high-volume trading, which today makes up a majority of all trades. Experts say it will help place limits on the reckless short-term speculation that threatens financial stability—as with JPMorgan Chase’s losing bet of $3 billion recently. A Robin Hood Tax would also assist in curtailing speculation in essentials, such as food and fuel. [Robinhoodtax.org]

The One Percent’s problem

Joseph E. Stiglitz writes: Let’s start by laying down the baseline premise: inequality in America has been widening for decades. We’re all aware of the fact. Yes, there are some on the right who deny this reality, but serious analysts across the political spectrum take it for granted. I won’t run through all the evidence here, except to say that the gap between the 1 percent and the 99 percent is vast when looked at in terms of annual income, and even vaster when looked at in terms of wealth—that is, in terms of accumulated capital and other assets. Consider the Walton family: the six heirs to the Walmart empire possess a combined wealth of some $90 billion, which is equivalent to the wealth of the entire bottom 30 percent of U.S. society. (Many at the bottom have zero or negative net worth, especially after the housing debacle.) Warren Buffett put the matter correctly when he said, “There’s been class warfare going on for the last 20 years and my class has won.”

So, no: there’s little debate over the basic fact of widening inequality. The debate is over its meaning. From the right, you sometimes hear the argument made that inequality is basically a good thing: as the rich increasingly benefit, so does everyone else. This argument is false: while the rich have been growing richer, most Americans (and not just those at the bottom) have been unable to maintain their standard of living, let alone to keep pace. A typical full-time male worker receives the same income today he did a third of a century ago.

From the left, meanwhile, the widening inequality often elicits an appeal for simple justice: why should so few have so much when so many have so little? It’s not hard to see why, in a market-driven age where justice itself is a commodity to be bought and sold, some would dismiss that argument as the stuff of pious sentiment.

Put sentiment aside. There are good reasons why plutocrats should care about inequality anyway—even if they’re thinking only about themselves. The rich do not exist in a vacuum. They need a functioning society around them to sustain their position. Widely unequal societies do not function efficiently and their economies are neither stable nor sustainable. The evidence from history and from around the modern world is unequivocal: there comes a point when inequality spirals into economic dysfunction for the whole society, and when it does, even the rich pay a steep price. [Continue reading…]

Divided America

In The New Geography of Jobs, Enrico Moretti writes: Menlo Park is a lively community in the heart of Silicon Valley, just minutes from Stanford University’s manicured campus and many of the Valley’s most dynamic high-tech companies. Surrounded by some of the wealthiest zip codes in California, its streets are lined with an eclectic mix of midcentury ranch houses side by side with newly built mini-mansions and low-rise apartment buildings. In 1969, David Breedlove was a young engineer with a beautiful wife and a house in Menlo Park. They were expecting their first child. Breedlove liked his job and had even turned down an offer from Hewlett-Packard, the iconic high-tech giant in the Valley. Nevertheless, he was considering leaving Menlo Park to move to a medium-sized town called Visalia. About a three-hour drive from Menlo Park, Visalia sits on a flat, dry plain in the heart of the agricultural San Joaquin Valley. Its residential neighborhoods have the typical feel of many Southern California communities, with wide streets lined with one-story houses, lawns with shrubs and palm trees, and the occasional backyard pool. It’s hot in the summer, with a typical maximum temperature in July of ninety-four degrees, and cold in the winter.

Breedlove liked the idea of moving to a more rural community with less pollution, a shorter commute, and safer schools. Menlo Park, like many urban areas at the time, did not seem to be heading in the right direction. In the end, Breedlove quit his job, sold the Silicon Valley house, packed, and moved the family to Visalia. He was not the only one. Many well-educated professionals at the time were leaving cities and moving to smaller communities because they thought those communities were better places to raise families. But things did not turn out exactly as they expected.

In 1969, both Menlo Park and Visalia had a mix of residents with a wide range of income levels. Visalia was predominantly a farming community with a large population of laborers but also a sizable number of professional, middle-class families. Menlo Park had a largely middle-class population but also a significant number of working-class and low-income households. The two cities were not identical—the typical resident of Menlo Park was somewhat better educated than the typical resident of Visalia and earned a slightly higher salary—but the differences were relatively small. In the late 1960s, the two cities had schools of comparable quality and similar crime rates, although Menlo Park had a slightly higher incidence of violent crime, especially aggravated assault. The natural surroundings in both places were attractive. While Menlo Park was close to the Pacific Ocean beaches, Visalia was near the Sierra Nevada range and Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks.

Today the two places could not be more different, but not in the way David Breedlove envisioned. The Silicon Valley region has grown into the most important innovation hub in the world. Jobs abound, and the average salary of its residents is the second highest in America. Its crime rate is low, its school districts are among the best in the state, and the air quality is excellent. Fully half of its residents have a college degree, and many have a PhD, making it the fifth best educated urban area in the nation. Menlo Park keeps attracting small and large high-tech employers, including most recently the new Facebook headquarters.

By contrast, Visalia has the second lowest percentage of college-educated workers in the country, almost no residents with a postgraduate degree, and one of the lowest average salaries in America. It is the only major city in the Central Valley that does not have a four-year college. Its crime rate is high, and its schools, structurally unable to cope with the vast number of non-English-speaking students, are among the worst in California. Visalia also consistently ranks among American cities with the worst pollution, especially in the summer, when the heat, traffic, and fumes from farm machines create the third highest level of ozone in the nation.

Not only are the two communities different, but they are growing more and more different every year. For the past thirty years, Silicon Valley has been a magnet for good jobs and skilled workers from all over the world. The percentage of college graduates has increased by two-thirds, the second largest gain among American metropolitan areas. By contrast, few high-paying jobs have been created in Visalia, and the percentage of local workers with a college degree has barely changed in thirty years—one of the worst performances in the country.

For someone like David Breedlove, a highly educated professional with solid career options, choosing Visalia over Menlo Park was a perfectly reasonable decision in 1969. Today it would be almost unthinkable. Although only 200 miles separate these two cities, they might as well be on two different planets. [Continue reading…]

Video: The One Percent

TED responds to criticism

This is the talk which TED earlier declined to post:

And this is Chris Anderson’s explanation about what happened:

Today TED was subject to a story so misleading it would be funny… except it successfully launched an aggressive online campaign against us.

The National Journal alleged we had censored a talk because we considered the issue of inequality “too hot to handle.” The story ignited a firestorm of outrage on Reddit, Huffington Post and elsewhere. We were accused of being cowards. We were in the pay of our corporate partners. We were the despicable puppets of the Republican party.

Here’s what actually happened.

At TED this year, an attendee pitched a 3-minute audience talk on inequality. The talk tapped into a really important and timely issue. But it framed the issue in a way that was explicitly partisan. And it included a number of arguments that were unconvincing, even to those of us who supported his overall stance. The audience at TED who heard it live (and who are often accused of being overly enthusiastic about left-leaning ideas) gave it, on average, mediocre ratings.

At TED we post one talk a day on our home page. We’re drawing from a pool of 250+ that we record at our own conferences each year and up to 10,000 recorded at the various TEDx events around the world, not to mention our other conference partners. Our policy is to post only talks that are truly special. And we try to steer clear of talks that are bound to descend into the same dismal partisan head-butting people can find every day elsewhere in the media.

We discussed internally and ultimately told the speaker we did not plan to post. He did not react well. He had hired a PR firm to promote the talk to MoveOn and others, and the PR firm warned us that unless we posted he would go to the press and accuse us of censoring him. We again declined and this time I wrote him and tried gently to explain in detail why I thought his talk was flawed.

So he forwarded portions of the private emails to a reporter and the National Journal duly bit on the story. And it was picked up by various other outlets.

And a non-story about a talk not being chosen, because we believed we had better ones, somehow got turned into a scandal about censorship. Which is like saying that if I call the New York Times and they turn down my request to publish an op-ed by me, they’re censoring me.

For the record, pretty much everyone at TED, including me, worries a great deal about the issue of rising inequality. We’ve carried talks on it in the past, like this one from Richard Wilkinson. We’d carry more in the future if someone can find a way of framing the issue that is convincing and avoids being needlessly partisan in tone.

Also, for the record, we have never sought advice from any of our advertisers on what we carry editorially. To anyone who knows how TED operates, or who has observed the noncommercial look and feel of the website, the notion that we would is laughable. We only care about one thing: finding the best speakers and the best ideas we can, and sharing them with the world. For free. I’ve devoted the rest of my life to doing this, and honestly, it’s pretty disheartening to have motives and intentions taken to task so viciously by people who simply don’t know the facts.

One takeaway for us is that we’re considering at some point posting the full archive from future conferences (somewhere away from the home page). Perhaps this would draw the sting from the accusations of censorship. Here, for starters, is the talk concerned. You can judge for yourself…

No doubt it will now, ironically, get stupendous viewing numbers and spark a magnificent debate, and then the conspiracy theorists will say the whole thing was a set-up!

OK… thanks for listening. Over and out.

The way Anderson tells the story it sounds simply like a case of someone getting turned down at an audition and then not being willing to accept a rejection. But given that Anderson describes this as an account of “what actually happened,” he fails to explain what appears to be a key component of the story: that he had written to Hanauer telling him that his talk “probably ranks as one of the most politically controversial talks we’ve ever run, and we need to be really careful when” to post it. He wrote “when” not “if” but later backtracked.

No doubt Anderson and the other folks at TED don’t appreciate the way Hanauer and his PR representatives have handled this and his talk certainly doesn’t rank as one of the most inspired TED talks, but was it really so politically controversial?

TED turns stupid

As readers here will know, I like TED talks. TED provides a great forum for lively, pithy presentations on “ideas worth spreading.”

Apparently, the organizers of TED have decided that the idea that widening income inequality is harming America is not an idea worth spreading.

National Journal reports: TED organizers invited a multimillionaire Seattle venture capitalist named Nick Hanauer – the first nonfamily investor in Amazon.com – to give a speech on March 1 at their TED University conference. Inequality was the topic – specifically, Hanauer’s contention that the middle class, and not wealthy innovators like himself, are America’s true “job creators.”

“We’ve had it backward for the last 30 years,” he said. “Rich businesspeople like me don’t create jobs. Rather they are a consequence of an ecosystemic feedback loop animated by middle-class consumers, and when they thrive, businesses grow and hire, and owners profit. That’s why taxing the rich to pay for investments that benefit all is a great deal for both the middle class and the rich.”

You can’t find that speech online. TED officials told Hanauer initially they were eager to distribute it. “I want to put this talk out into the world!” one of them wrote him in an e-mail in late April. But early this month they changed course, telling Hanauer that his remarks were too “political” and too controversial for posting.

Not only was this decision dumb — it was also bizarre.

Just six months ago TED posted Richard Wilkinson’s talk: “How economic inequality harms societies.”

Wilkinson is the co-author of The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger which documents in great detail how inequality worsens social problems and equality promotes social health — ideas worth spreading in 2011 but not 2012?

Hopefully TED will review their decision on Hanauer’s talk and acknowledge that what they did was dumb — that would be the smart thing to do. After all, Hanauer just appeared on Charlie Rose and he’s been on NPR, neither of which can be described as venues for political radicalism.

Hanauer was interviewed on NPR’s Weekend Edition in December:

Sorry! The lifestyle you ordered is currently out of stock

Teacher Liam Taylor leads Occupy London tours every couple of weeks through Canary Wharf, the privately-owned, guarded riverside oasis of wealth in Tower Hamlets where nine of the world’s biggest banks trade, lend and advise clients.

Bloomberg reports: Bank security guards in London lock the doors when they see Liam Taylor coming.

At a time of protests in March 2011, the secondary school teacher and a dozen others pushed through the revolving doors of Barclays Plc’s headquarters in the Canary Wharf financial district of London. He led placard-waving chants to protest bonuses and tax avoidance.

The British bank was handing out 65.5 million pounds ($106 million) to eight executives, including Chief Executive Officer Robert Diamond, whom Taylor has never met. Meanwhile, the council of the poverty-mired surrounding London neighborhood of Tower Hamlets was slashing 72 million pounds from its taxpayer- funded budget.

Here, where two worlds collide, the 26-year-old umbrella- toting teacher plays an active role in the Occupy London protest movement. Tower Hamlets has one of the highest rates of young people receiving jobless benefits in London, the highest proportion of poor children and older people in England and the worst child poverty in the U.K.

In its midst is Canary Wharf, a privately owned, guarded riverside oasis of wealth where Taylor leads Occupy tours every couple of weeks. Nine of the world’s biggest banks trade, lend and advise clients here. His message: This is where the wealthy 1 percent enrich themselves by avoiding tax, racking up debt, selling risky investments and using public funds for bailouts. They do so at the expense of the remaining 99 percent, who bear the burden of higher taxes and fewer public services, he says.

“These huge glass towers you can see around us are all in Tower Hamlets, and yet Tower Hamlets remains the borough with the highest rate of child poverty,” says the soft-spoken Taylor, who has blue eyes and cropped red hair. “The bonuses are being paid out of money which should have been paid in tax to provide public services.”

Canary Wharf is the base for companies that pay some of the highest salaries in the world. They include Barclays and HSBC Holdings Plc of the U.K., Switzerland’s Credit Suisse Group AG and the European operations of U.S.-based Citigroup Inc., JPMorgan Chase & Co., Morgan Stanley and Bank of America Corp.

Protests over economic inequality erupted around the world again last week. After a year of Occupy and trade union demonstrations in London, the sense of unfairness is growing as support for the U.K. government erodes. The ruling coalition of Conservative and Liberal Democrat parties lost hundreds of seats in last week’s local-council elections, although London’s Conservative Mayor Boris Johnson retained office.

British austerity measures are taking effect just as the U.K. enters its first double-dip recession since the 1970s. The budgets of Tower Hamlets and the deprived boroughs of Hackney and Newham were cut the most among London neighborhoods last year while wealthy Richmond-upon-Thames’s was reduced the least.

Income inequality among working-age people has risen faster in the U.K. than in any other wealthy Western country since 1975, according to the Paris-based Organization for Economic Cooperation & Development. London and the finance industry are the driving forces behind the rise, according to Mark Stewart, an economics professor at the University of Warwick.

“There is a groundswell of increasing concern with the scale of inequality,” says Richard Wilkinson, coauthor with Kate Pickett of the book, “The Spirit Level.” They make the case that more-unequal societies have lower life expectancies and more mental illness, violence, teenage pregnancies and incarceration, resulting in less trust.

Nowhere is the divide between rich and poor more evident than in Tower Hamlets and Canary Wharf. Many of Canary Wharf’s 95,000 workers travel to and from the skyscrapers on trains that pass under or over the 240,000 residents of Tower Hamlets. Taylor’s students say commuters on trains look right through them. A four-lane highway and railway separate Canary Wharf from the rest of the borough. There are guarded checkpoints for cars.

Canary Wharf’s shiny underground malls are decked with advertisements for products including a Citigroup (C) account for those with an “international lifestyle.” The grubby streets of Tower Hamlets feature empty spaces covered with graffiti: “Sorry! The lifestyle you ordered is currently out of stock.” [Continue reading…]

A web of privilege supports this so-called meritocracy

Gary Younge writes: Shortly after Mitt Romney’s failed 2008 campaign for the Republican nomination his son Tagg set up a private equity fund with the campaign’s top fundraiser. One of the first donors was his mum, Anne. Next came several of his dad’s financial backers. Tagg had no experience in the world of finance, but after two years in the middle of a deep recession the company had netted $244m from just 64 investors.

Tagg insists that neither his name nor the fact that his father had made it clear he would run for the presidency again had anything to do with his success. “The reason people invested in us is that they liked our strategies,” he told the New York Times.

Class privilege, and the power it confers, is often conveniently misunderstood by its beneficiaries as the product of their own genius rather than generations of advantage, stoutly defended and faithfully bequeathed. Evidence of such advantages is not freely available. It is not in the powerful’s interest for the rest of us to know how their influence is attained or exercised. But every now and then a dam bursts and the facts come flooding forth. [Continue reading…]

The other America, 2012: confronting the poverty epidemic

Sasha Abramsky writes: Clarksdale, Mississippi, might seem an unlikely starting point for a meditation on twenty-first-century American inequality. After all, the music the town’s fame rests on is born of the sorrow and racial exploitations of another century. Clarksdale proudly markets itself as the home of the blues: the world’s best blues musicians still come to jam in the little Delta town where W.C. Handy once lived, where Bessie Smith died and where Robert Johnson supposedly made his infamous pact with the devil at a crossroads on the edge of town.

But Clarksdale is also the site of a very different crossroads, one in many ways emblematic of what America is becoming: a place of stunning divides and dramatically disparate life expectations between rich and poor. The side streets of central Clarksdale are lined with tiny, dilapidated wooden homes. Most residents here make do without basic services and amenities, including anything beyond a bare-bones education, and many lack access to the broader cash economy. In contrast, the stately old townhouses in the historic district—places where several Mississippi governors grew up, where the young Tennessee Williams ran around while staying with his grandparents—look like the scenic backdrop to a romantic film set in the antebellum South. And the newer, more palatial mansions in the suburbs ringing the town could serve as staging grounds for a reality TV show on the nouveau riche.

In the poorer section of Clarksdale, in a subsidized housing unit about the size of a small boat’s cabin, lives 88-year-old Amos Harper, a jack-of-all-trades who grew up in a sharecropping family. Harper spent decades doing everything from farmwork to interstate tractor-trailer transport. These days, he gets up early to supplement his $765 monthly Social Security check, collecting cans from the gutters and trading them in for 49 cents per pound. When he isn’t doing that, he’s mowing lawns and running errands for several of the town’s richer residents, including Bill Luckett.

Luckett and his wife live in a huge house designed by architect E. Fay Jones, a Frank Lloyd Wright mentee. Every detail, from the high ceilings to the sunken rooms, has been carefully planned. The larger-than-life home complements the larger-than-life persona of Luckett, a burly 64-year-old attorney and real estate developer with a shock of gray hair who is “president of everything from a country club to a hunting club,” as he puts it. Luckett serves on a state legal aid board and various educational advisory boards, and he counts among his acquaintances some of the country’s top politicians and entertainers.

He also considers Harper a friend, although, as Luckett would be the first to acknowledge, the friendship is deeply unequal. Until age slowed him down, Harper would routinely show up at the Ground Zero blues club, a raucous place Luckett owns with actor Morgan Freeman, showing off dance moves that Luckett says are some of the best in town.

For Luckett, Clarksdale’s imbalances are indicative of broader fissures and inequities in Mississippi—and, he believes, across America. Angry at the way the political system is ignoring poverty, Luckett ran for governor last year on an anti-poverty and invest-in-education platform. He came in a strong second in the Democratic primary, though in a state as heavily Republican as Mississippi, that didn’t necessarily count for much. “I’d never intended to get into politics,” he explains over a glass of red wine in one of his living rooms. But, he says, lack of investment in public education, an increasingly regressive tax system and other challenges pushed him into the fray. “America has never had as greedy a top 1 percent as we have now. The inequality has reached dangerous proportions.”

Unfortunately, Luckett is a rare exception in Mississippi politics. The state’s leadership is exemplified by ex-governor Haley Barbour and current governor Phil Bryant, who both won election by forging alliances between country club denizens and the culturally conservative white working class, which both preach the virtues of shrinking government, rolling back regulations and cutting social services. “When you get a white guy walking out of his rusty trailer into his pickup truck and he’s got a Vote Republican placard in his yard, then you’ve reached the height of stupidity,” Luckett says.

Sadly, this too is reflective of the nation. [Continue reading…]

In nothing we trust

National Journal reports: Johnny Whitmire shuts off his lawn mower and takes a long draw from a water bottle. He sloshes the liquid from cheek to cheek and squirts it between his work boots. He is sweating through his white T-shirt. His jeans are dirty. His middle-aged back hurts like hell. But the calf-high grass is cut, and the weeds are tamed at 1900 W. 10th St., a house that Whitmire and his family once called home. “I’ve decided to keep the place up,” he says, “because I hope to buy it back from the bank.”

Whitmire tells a familiar story of how public and private institutions derailed an American’s dream: In 2000, he bought the $40,000 house with no money down and a $620 monthly mortgage. He made every payment. Then, in the fall of 2010, his partially disabled wife lost her state job. “Governor [Mitch] Daniels slashed the budget, and they looked for any excuse to squeeze people out,” Whitmire says. “We got lost in that shuffle—cut adrift.” The Whitmires couldn’t make their payments anymore.

They applied for a trial loan-modification through an Obama administration program, and when it was granted, their monthly bill fell to $473.87. But, like nearly a million others, the modification was canceled. After charging the lower rate for three months, their mortgage lender reinstated the higher fee and billed the family $1,878.88 in back payments. Whitmire didn’t have that kind of cash and couldn’t get it, so he and his wife filed for bankruptcy. His attorney advised him to live in the house until the bank foreclosed, but “I don’t believe in a free lunch,” Whitmire says. He moved out, leaving the keys on the kitchen table. “I thought the bank should have them.”

A year later, City Hall sent him salt for his wounds: a $300 citation for tall grass at 1900 W. 10th St. Telling the story, he swipes dried grass from his jeans and shakes his head. “The city dinged me for tall weeds at my bank’s house.” After another pull from the water bottle, Whitmire kicks a steel-toed boot into the ground he once owned. “You can’t trust anybody or anything anymore.”

Whitmire is an angry man. He is among a group of voters most skeptical of President Obama: noncollege-educated white males. He feels betrayed—not just by Obama, who won his vote in 2008, but by the institutions that were supposed to protect him: his state, which laid off his wife; his government in Washington, which couldn’t rescue homeowners who had played by the rules; his bank, which failed to walk him through the correct paperwork or warn him about a potential mortgage hike; his city, which penalized him for somebody else’s error; and even his employer, a construction company he likes even though he got laid off. “I was middle class for 10 years, but it’s done,” Whitmire says. “I’ve lost my home. I live in a trailer now because of a mortgage company and an incompetent government.” [Continue reading…]

Growth of income inequality is worse under Obama than Bush

Matt Stoller writes: Yesterday, the President gave a speech in which he demanded that Congress raise taxes on millionaires, as a way to somewhat recalibrate the nation’s wealth distribution. His advisors, like Gene Sperling, are giving speeches talking about the need for manufacturing. A common question in DC is whether this populist pose will help him win the election. Perhaps it will. Perhaps not. Romney is a weak candidate, cartoonishly wealthy and from what I’ve seen, pretty inept. But on policy, there’s a more interesting question.

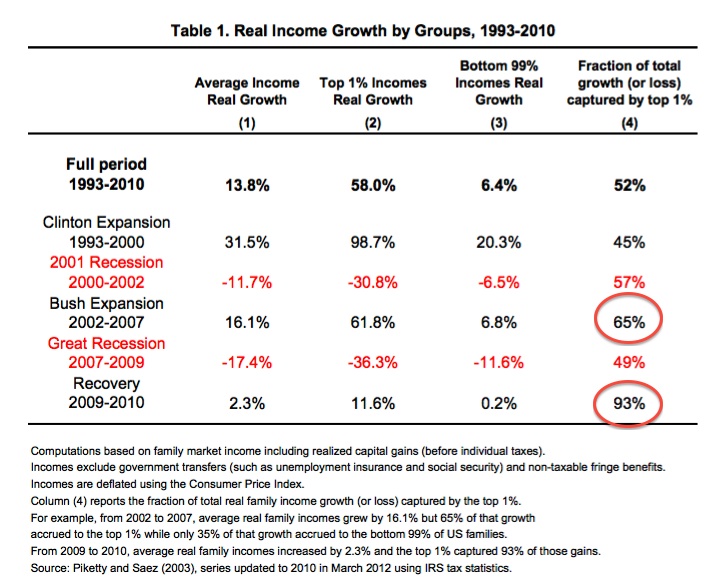

A better puzzle to wrestle with is why President Obama is able to continue to speak as if his administration has not presided over a significant expansion of income redistribution upward. The data on inequality shows that his policies are not incrementally better than those of his predecessor, or that we’re making progress too slowly, as liberal Democrats like to argue. It doesn’t even show that the outcome is the same as Bush’s. No, look at this table, from Emmanuel Saez (h/t Ian Welsh). Check out those two red circles I added.

Yup, under Bush, the 1% captured a disproportionate share of the income gains from the Bush boom of 2002-2007. They got 65 cents of every dollar created in that boom, up 20 cents from when Clinton was President. Under Obama, the 1% got 93 cents of every dollar created in that boom. That’s not only more than under Bush, up 28 cents. In the transition from Bush to Obama, inequality got worse, faster, than under the transition from Clinton to Bush. Obama accelerated the growth of inequality.

The rich get even richer

Steven Rattner writes: New statistics show an ever-more-startling divergence between the fortunes of the wealthy and everybody else — and the desperate need to address this wrenching problem. Even in a country that sometimes seems inured to income inequality, these takeaways are truly stunning.

In 2010, as the nation continued to recover from the recession, a dizzying 93 percent of the additional income created in the country that year, compared to 2009 — $288 billion — went to the top 1 percent of taxpayers, those with at least $352,000 in income. That delivered an average single-year pay increase of 11.6 percent to each of these households.

Still more astonishing was the extent to which the super rich got rich faster than the merely rich. In 2010, 37 percent of these additional earnings went to just the top 0.01 percent, a teaspoon-size collection of about 15,000 households with average incomes of $23.8 million. These fortunate few saw their incomes rise by 21.5 percent.

The bottom 99 percent received a microscopic $80 increase in pay per person in 2010, after adjusting for inflation. The top 1 percent, whose average income is $1,019,089, had an 11.6 percent increase in income.