The Economist reports: In August 2014 Boko Haram fighters surged through Madagali, an area in north-east Nigeria. They butchered, burned and stole. They closed schools, because Western education is sinful, and carried off young girls, because holy warriors need wives.

Taru Daniel escaped with his father and ten siblings. His sister was not so lucky: the jihadis kidnapped her and took her to their forest hideout. “Maybe they forced her to marry,” Mr Daniel speculates. Or maybe they killed her; he does not know.

He is 23 and wears a roughed-up white T-shirt and woollen hat, despite the blistering heat in Yola, the town to which he fled. He has struggled to find a job, a big handicap in a culture where a man is not considered an adult unless he can support a family. “If you don’t have money you cannot marry,” he explains. Asked why other young men join Boko Haram, he says: “Food no dey. [There is no food.] Clothes no dey. We have nothing. That is why they join. For some small, small money. For a wife.”

Some terrorists are born rich. Some have good jobs. Most are probably sincere in their desire to build a caliphate or a socialist paradise. But material factors clearly play a role in fostering violence. North-east Nigeria, where Boko Haram operates, is largely Islamic, but it is also poor, despite Nigeria’s oil wealth, and corruptly governed. It has lots of young men, many of them living hand to mouth. It is also polygamous: 40% of married women share a husband. Rich old men have multiple spouses; poor young men are left single, sex-starved and without a stable family life. Small wonder some are tempted to join Boko Haram.

Globally, the people who fight in wars or commit violent crimes are nearly all young men. Henrik Urdal of the Harvard Kennedy School looked at civil wars and insurgencies around the world between 1950 and 2000, controlling for such things as how rich, democratic or recently violent countries were, and found that a “youth bulge” made them more strife-prone. When 15-24-year-olds made up more than 35% of the adult population — as is common in developing countries — the risk of conflict was 150% higher than with a rich-country age profile.

If young men are jobless or broke, they make cheap recruits for rebel armies. And if their rulers are crooked or cruel, they will have cause to rebel. Youth unemployment in Arab states is twice the global norm. The autocrats who were toppled in the Arab Spring were all well past pension age, had been in charge for decades and presided over kleptocracies. [Continue reading…]

Category Archives: inequality

How a few billionaires could help close the world’s poverty gap

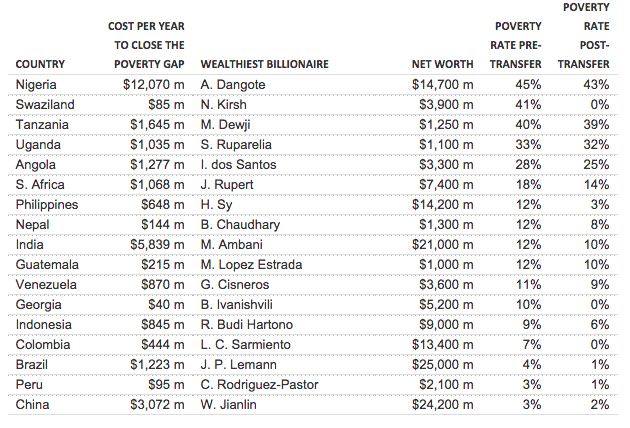

Laurence Chandy, Lorenz Noe and Christine Zhang write: What difference could a philanthropic donation from the world’s richest people make?

To explore this question, we begin by identifying those developing countries that are home to a least one billionaire. (Our analysis is restricted to billionaires by data, not by the potential largesse of the world’s multi-millionaires. We focus our attention on billionaires in the developing world given the traditional focus of philanthropy on domestic causes.) Let’s assume that the richest billionaire in each country agrees to give away half of his or her current wealth among his or her fellow citizens, disbursed evenly over the next 15 years, roughly in accordance with the Giving Pledge promoted by Bill Gates. That money would be used exclusively to finance transfers to poor people based on their current distance from the poverty line. Transfers would be sustained at the same level for the full 15-year period with the aim of providing a modicum of income security that might allow beneficiaries to sustainably escape from poverty by 2030.

The following table summarizes the key results. In each of three countries — Colombia, Georgia, and Swaziland — a single individual’s act of philanthropy could be sufficient to end extreme poverty with immediate effect. Swaziland is an especially striking case as it is among the world’s poorest countries, with 41 percent of its population living under the poverty line. In Brazil, Peru, and the Philippines, poverty could be more than halved, or eliminated altogether if the billionaires could be convinced to match Mark Zuckerberg’s example and increase their donation to 99 percent of their wealth. [Continue reading…]

This billionaire thinks you should be paid more

At work as at home, men reap the benefits of women’s ‘invisible labor’

Soraya Chemaly writes: Men today do a higher share of chores and household work than any generation of men before them. Yet working women, especially working mothers, continue to do significantly more.

On any given day, one fifth of men in the US, compared to almost half of all women do some form of housework. Each week, according to Pew, mothers spend nearly twice as long as fathers doing unpaid domestic work. But while it’s important to address inequality at home, it’s equally critical to acknowledge the way these problems extend into the workplace. Women’s emotional labor — which can involve everything from tending to others’ feelings to managing family dynamics to writing thank-you notes — is a big issue that’s rarely discussed.

In the early 1980s, University of California, Berkeley sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild coined the term “emotional labor” in her book The Managed Heart. Hochschild observed that women make up the majority of service workers — flight attendants, food service workers, customer service reps — as well as the majority of of child-care and elder-care providers. All of these positions require emotional effort, from smiling on demand to prioritizing the happiness of the customer over one’s own feelings. [Continue reading…]

How the other 1% lives: Wealth gap not the only way in which global elite is taking advantage

By Anna Childs, The Open University

Oxfam’s latest report, focused on an increasingly obscene wealth inequality and the stranglehold exerted by a global elite, had one central message: The era of tax havens that have made this possible must be brought to an end.

The report – An Economy for the 1% – was timed as a call to action for influential delegates to the annual meeting of the World Economic Forum taking place in Davos, Switzerland.

The headline numbers showed that the top 1% own as much wealth as the other 99% and – even more startling – that the richest 62 individuals own more wealth than the poorest half of the world’s population (compared to 388 individuals in 2010). To put this into stark perspective, this group of 62 people own as much as the 3.6 billion people on the bottom of the heap.

Oxfam makes it clear that this distribution of wealth is not some incidental byproduct of rising worldwide prosperity. Since 2000, the poorest half of the world’s population has received just 1% of the total increase in global wealth, while 50% of that has gone to the 1% of people on the top of the pile – about 74m people. While the richest have been getting richer, the combined wealth of the poorest half of the planet has fallen by US$1 trillion (41%) in the past five years alone.

The life and death of King Coal

By Ben Curtis, Cardiff University

The reign of King Coal is a story which is central to fully understanding modern Britain. Coal powered the industrial revolution, employed over a million miners at the industry’s height, shaped and sustained communities across the country, and has played a key role in the UK’s political economy. With the closure of Kellingley colliery, the country’s last deep mine, in December 2015, a defining chapter in British history comes to an end.

Although it had been mined in small quantities in Britain since Roman times, the story of coal as a major industry begins with the industrial revolution. From the 18th century onwards, demand for coal began to grow at an increasing rate. Several factors drove this, but its most important uses were as a fuel for steam-powered engines, in ironworks and metal smelting, and for domestic energy consumption in growing cities and towns. Then in the 19th century, coal grew to become the biggest industry in Britain in terms of workforce. It expanded from 109,000 workers in 1830 to nearly 1.1 million in 1913.

The early years of the 20th century proved to be the industry’s zenith, however. The period between World War I and II was one of crisis and catastrophic decline for coal. Its seemingly unassailable position was undermined by a series of economic factors – including the decision in 1925 by the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Winston Churchill, to return sterling to the gold standard. This had the inadvertent effect of making British coal too expensive in its important, but increasingly vulnerable, overseas markets.

Coalbrookdale by Night by Philip James de Loutherbourg

As labour was the biggest cost in coal production, employers’ attempts to cut wages led to a series of bitter industrial relations disputes in the 1920s. The most well-known is the 1926 general strike, called by the Trades Union Congress in support of the miners. Although the general strike itself only lasted nine days, communities around the country’s coalfields held out for a further six months before finally conceding defeat.

What next after Paris? Time to listen to those most at risk from climate change

By James Dyke, University of Southampton

Pick any day over the past few weeks and the mainstream media would have told you that the COP21 Paris climate change negotiations were crucial and productive, an irrelevant sideshow, doomed to failure, or even humanity’s last ditch attempt to avoid climate catastrophe.

Dig a little deeper into the internet and you will discover that such United Nations events are in fact an attempt to establish a world government, replete with eye-watering taxes.

Conspiracy theories aside, what actually happened in Paris is that humans came up with an agreed plan to put a brake on climate change. We won’t reverse global warming but we should slow it down.

If we don’t come to our collective senses and rapidly reduce carbon emissions, then we will have to revert to drastic geoengineering to rein in further warming. There is no guarantee that such climate brakes will work. If they fail, our civilisation will be on a collision course with a hotter planet.

How does someone become an alien in the country of their birth?

America is a country with few deep-rooted natives. Nearly everyone’s ancestral tree leads somewhere else. In spite of this, the mark of foreignness is skin color. If you’re white and have an American accent, no one’s going to ask you when your family emigrated here — even though, without exception, every single white American’s roots lead overseas.

The truism that this is a nation of immigrants, repeatedly gets denied by a white America endowed with a sense of belonging which often doubts the capacity of non-whites to be full equals in sharing an American identity.

How then, can someone who knows no other country than this one and yet who is perceived and treated as though in some subtle or crude sense they are foreign, fully share in the experience of belonging that every human being deserves?

If at this moment of heightened xenophobia, we look at alienation through the narrow prism of counter-terrorism and only ask how just a handful of individuals become radicalized, we are likely to ignore the implications of much wider issues, such as inequality, cultural identity, and citizenship.

America succeeds or fails by one measure alone: its ability to sustain an inclusive society.

Donald Trump could not currently threaten this inclusivity were it not for the fact that that he speaks for so many other white Americans who have conferred on themselves the right to determine who does or does not belong here.

America doesn’t need to wall itself in; what it needs is fewer self-appointed gatekeepers.

This is what happens when modernity fails all of us

Muqtedar Khan writes: Muslims were told that if they embraced modernity they would become free and prosperous. But modernity has failed many Muslims in the Muslim World. It brought imperialism, occupation, wars, division and soul stifling oppression by home states and foreign powers. Today the most important element of modernity, the modern state, is crumbling across the Arab World, precipitating chaos and forcing Muslims to seek refuge abroad.

For Muslims in the West, unjust foreign policies of their new homes, persistent and virulent Islamophobia, state surveillance, discrimination and demonization can be at best alienating and at worst radicalizing. Perhaps it is those whom modernity has failed at home and abroad who are tempted by the fatal attraction of extremism.

But why Muslims only you might ask? My answer: Open your eyes and look, modernity is failing non-Muslims too. Egregious income inequalities, police brutality, rampant institutionalized racism, mass-killings, drugs, gang violence, sexual predatory behaviors, militarization of police, diminishing civil rights as the state becomes more intrusive and rising rhetoric of intolerance from mainstream politicians — they are symptoms of institutional failures, extremism and even domestic terrorism.

We can combat extremism only by recognizing and resisting it everywhere. But we must make the promise of modernity a reality for all in order to render the appeal of radical utopias less attractive. [Continue reading…]

Black-Palestinian Solidarity: When I see them I see us

‘Black-Palestinian Solidarity’ draws parallels between two…

Palestinian-American poet Remi Kanazi and Mari Morales-Williams of the Black Youth Project 100 interviewed on MSNBC.

It’s time to move beyond growth for growth’s sake

Martin Kirk writes: Economic growth sits at the root of all plans to tackle poverty. The two concepts – growth and poverty reduction – are treated as practically interchangeable. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the new UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which promise to eradicate poverty ‘in all its forms everywhere’ by 2030. The entire formula for success rests on economic growth; at least 7 per cent per annum in the least developed countries, and higher levels of economic productivity across the board. Goal 8 is entirely dedicated to this objective.

This feels intuitive and logical. If economic growth equals more money, and poverty equals a lack of money, then economic growth equals less poverty. And this is, of course, the prevailing logic for all human development. The idea that if you’re not growing you must be dying is writ large. Every country, every company, every individual must grow their material wealth over time; both the whole and every one of its parts must be on a constant growth curve. Taken together, we might see this as a form of totalitarianism – the totalitarian imperative of growth.

There are two problems with economic growth as a measure of wellbeing. First, the correlation between economic growth and poverty reduction is weak. It’s a reminder that intuition and ‘common sense’ do not always correspond to evidence. Globally, the trends are clear. Since 1990, global gross domestic product (GDP) has increased 271 per cent, and yet both the number of people living on less than $5 a day, and the number of people going hungry (using the Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN’s definition of available calories for the mid‑point between normal and intense activity levels) have also increased, by 10 per cent and 9 per cent respectively. Add to that the wage stagnation across the developed world, and increasing inequality both within and between countries pretty much everywhere, and the shakiness of this basic logic becomes evident. Aggregate economic growth does not translate into less poverty, which is the stated objective of the SDGs.

This is not to suggest that a larger economic pie doesn’t benefit many people; it does. But that is simply not the same as saying that it reduces poverty. We live in a world where 95 per cent of all income from growth goes to the richest 40 per cent, and the concept of trickle-down neoliberal economics has been shown, in the words of Alex Andreou in The Guardian last year, to be ‘the greatest broken promise of our lifetimes’. [Continue reading…]

Belgium is a failed state

Tim King (editor of European Voice for The Economist) writes: [Molenbeek] is one of the most densely populated parts of Brussels, but its population is only 95,000. And it is not that the entire borough is a no-go zone. The lawlessness problems are concentrated in much smaller areas.

All of which raises the question of why Molenbeek’s problems have been allowed to persist for so long. This is not a task on the same scale as reviving the South Bronx or redressing the industrial blight of Glasgow. The nearest parallel I can think of is Brixton, a London suburb, three miles south of Westminster. Blighted by wartime bomb damage, then home to large contingents of West Indian immigrants in the 1950s and 1960s, it suffered race riots in the 1980s. But much of Brixton has been turned round, so why not Molenbeek?

The answers are an indictment of the Belgian political establishment and of successive reforms over the past 40 years.

Those failures are perhaps one part politics and government; one part police and justice; one part fiscal and economic. In combination they created the vacuum that is being exploited by jihadi terrorists.

Belgium has the trappings of western political structures, but in practice those structures are flawed and have long been so. The academics Kris Deschouwer and Lieven De Winter gave a succinct, authoritative account of the development of political corruption and clientelism in an essay published back in 1998 as part of the piquantly titled book “Où va la Belgique?” (Whither Belgium?)

Almost from the beginning, they explain, the state suffered problems of political legitimacy. [Continue reading…]

In a society where everyone is ready to defend the common good, corruption doesn’t pay

Suzanne Sadedin writes: By making a few alterations to the composition of the justice system, corrupt societies could be made to transition to a state called ‘righteousness’. In righteous societies, police were not a separate, elite order. They were everybody. When virtually all of society stood ready to defend the common good, corruption didn’t pay.

Among honeybees and several ant species, this seems to be the status quo: all the workers police one another, making corruption an unappealing choice. In fact, the study showed that even if power inequalities later re-appeared, corruption would not return. The righteous community was extraordinarily stable.

Not all societies could make the transition. But those that did would reap the benefits of true, lasting harmony. An early tribe that made the transition to righteousness might out-compete more corrupt rivals, allowing righteousness to spread throughout the species. Such tribal selection is uncommon among animals other than eusocial insects, but many researchers think it could have played a role in human evolution. Hunter-gatherer societies commonly tend toward egalitarianism, with social norms enforced by the whole group rather than any specially empowered individuals. [Continue reading…]

Climate change is a reverse Robin Hood: stealing from the poor countries and giving to the rich ones

Quartz reports: Just when you thought the news about climate change couldn’t get any worse, consider this.

Not only will global warming put a massive dent in the world’s GDP over the coming decades, but it “is essentially a massive transfer of value from the hot parts of the world to the cooler parts of the world,” according to a new study in Nature. “This is like taking from the poor and giving to the rich.”

Researchers Stanford University analyzed 166 countries over a 50-year period (from 1960 to 2010) and compared economic output when country’s experienced normal temperature to abnormally cold or warm temperatures. Controlling for factors such as geography, economic changes, and global trade shifts, they found the optimum temperature where humans are good at producing stuff: 55ºF (13ºC).

Applying this finding to climate change forecasts, they found that 77% of countries will experience a decline in per capita incomes by 2099, with the average person’s income shrinking by 23%. Unusually high temperatures will hurt agriculture, economic production, and overall health, researchers say. [Continue reading…]

The world has 21 million slaves – and millions of them live in the West

Wagner Moura writes: As a child growing up in one of Brazil’s poorest regions, I was used to seeing well-off families take in girls from poorer ones to come live in their homes and be brought up as one of their own. This was seen as an act of kindness. It was only much later that I came to see it for what it really was: these young girls, who would do all the domestic chores all day long in return only for food and a roof over their heads, were in fact modern slaves.

There are 21 million modern slaves in the world today, most of them women and girls hiding in plain sight in poor and rich countries alike – 7% of today’s slaves live in North America or the European Union. From trafficking and sexual exploitation to work in private homes, agriculture, fishing, construction and manufacturing, modern slavery is not only a crime, it is big business. It generates some $150bn in illegal profits every year, according to an estimate by the International Labour Organization (ILO).

Poverty is at the root of it, as is lack of awareness by both victims and the general public. Forced labor affects the most vulnerable and least protected people, perpetuating a vicious cycle of poverty and dependency. Women, low-skilled migrant workers, children, indigenous peoples and other groups suffering discrimination on different grounds are disproportionately affected. And many victims don’t even consider themselves to be slaves – working to pay off a debt passed down through generations, or being a servant in a private home from dusk to dawn is the only life some have ever known. At the same time, you may be eating food picked by modern slaves, or wearing clothes made with slave labor without realizing it. [Continue reading…]

Inside Britain’s secretive Bullingdon Club

Der Spiegel reports: The Bullingdon and other dinner clubs are seeds of power in the United Kingdom, and not just because membership provides influence. Members also gain access to a group of like-minded individuals who will later assume leading roles — allies for life, just as it has always been.

If there is a stable core of British society that has remained unchanged for centuries, it is the upper class. Unlike the elites on the European continent, the leadership clique in Britain was largely spared from revolutions and uprisings. For generations, the children of the country’s powerful families have attended boarding schools like Eton, Winchester and Harrow, followed by the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge. It is a form of patronage that Britons simply refer to as tradition.

Not everyone has fond memories of those colorful student days. David Cameron was not only a member of the Bullingdon Club, but also of the Piers Gaveston Society, a club for younger students well known for its excesses. If a new biography about the premier is to be believed, Cameron, during one Gaveston party, placed his private parts into the mouth of a dead pig as part of an initiation ritual. The affair was lampooned in the press as “Pig-gate,” and had the entire country laughing at the prime minister. Cameron initially kept mum about the incident before explicitly denying it and his spokeswoman refuses to dignify the book with an official statement.

The most amazing part of the story isn’t the story as such, but the fact that most in Britain think it could be true. Few in the UK are surprised anymore by the excesses and affairs of the powerful at Westminster, a place that has long been viewed as sleazy and tainted. In the summer, to name just one recent example, the Sun published photos of Baron Sewel, a member of the House of Lords, who was photographed, half-naked, snorting cocaine with prostitutes.

There is a direct relationship between the excesses of these men and their lives as university students. One of the traditions at the Bullingdon Club was to invite prostitutes to a group breakfast. Excesses are part of the careers of these men rather than exceptions; they are part of the British elite’s DNA. [Continue reading…]

Pope Francis’s reception in the U.S. from the left and the right

Gerard O’Connell writes: Pope Francis comes to embrace all the people of the United States and is likely to encourage them to renew their devotion to family life and their understanding of the demands of solidarity as well as the responsible use of their global power.

As we have read in his programmatic document, “The Joy of the Gospel,” and as he spelled out clearly in the encyclical “Laudato Si’, on Care for Our Common Home,” this Jesuit pope from Argentina is calling Christians to a new simplicity of life and a depth of spirit that replaces materialism, hyper-individualism and the pursuit of constant pleasure with an integrity that knows what it is to sacrifice, to live in compassion and solidarity, to work for the common good, to care for creation, to show mercy and to attempt to pattern our lives after Jesus himself. His radical message is clear, simple and firmly rooted in the Gospels, which he never tires of encouraging people to read. [Continue reading…]

Jesus said to Rush Limbaugh, “Go and sell your possessions and give to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven; and come, follow Me.” But when Rush heard this statement, he went away grieving; for he was one who owned much property. (Matthew 19)

Jesus wouldn’t have been welcome on Fox News. Indeed, as an undocumented Palestinian, he wouldn’t have even made it through U.S. Immigration.

Guns, germs, and steal

We have all been raised to believe that civilization is, in large part, sustained by law and order. Without complex social institutions and some form of governance, we would be at the mercy of the law of the jungle — so the argument goes.

But there is a basic flaw in this Hobbesian view of a collective human need to tame the savagery in our nature.

For human beings to be vulnerable to the selfish drives of those around them, they generally need to possess things that are worth stealing. For things to be worth stealing, they must have durable value. People who own nothing, have little need to worry about thieves.

While Jared Diamond has argued that civilization arose in regions where agrarian societies could accumulate food surpluses, new research suggests that the value of cereal crops did not derive simply from the fact that the could be stored, but rather from the fact that having been stored they could subsequently be stolen or confiscated.

Joram Mayshar, Omer Moav, Zvika Neeman, and Luigi Pascali write: In a recent paper (Mayshar et al. 2015), we contend that fiscal capacity and viable state institutions are conditioned to a major extent by geography. Thus, like Diamond, we argue that geography matters a great deal. But in contrast to Diamond, and against conventional opinion, we contend that it is not high farming productivity and the availability of food surplus that accounts for the economic success of Eurasia.

- We propose an alternative mechanism by which environmental factors imply the appropriability of crops and thereby the emergence of complex social institutions.

To understand why surplus is neither necessary nor sufficient for the emergence of hierarchy, consider a hypothetical community of farmers who cultivate cassava (a major source of calories in sub-Saharan Africa, and the main crop cultivated in Nigeria), and assume that the annual output is well above subsistence. Cassava is a perennial root that is highly perishable upon harvest. Since this crop rots shortly after harvest, it isn’t stored and it is thus difficult to steal or confiscate. As a result, the assumed available surplus would not facilitate the emergence of a non-food producing elite, and may be expected to lead to a population increase.

Consider now another hypothetical farming community that grows a cereal grain – such as wheat, rice or maize – yet with an annual produce that just meets each family’s subsistence needs, without any surplus. Since the grain has to be harvested within a short period and then stored until the next harvest, a visiting robber or tax collector could readily confiscate part of the stored produce. Such ongoing confiscation may be expected to lead to a downward adjustment in population density, but it will nevertheless facilitate the emergence of non-producing elite, even though there was no surplus.

This simple scenario shows that surplus isn’t a precondition for taxation. It also illustrates our alternative theory that the transition to agriculture enabled hierarchy to emerge only where the cultivated crops were vulnerable to appropriation.

- In particular, we contend that the Neolithic emergence of fiscal capacity and hierarchy was conditioned on the cultivation of appropriable cereals as the staple crops, in contrast to less appropriable staples such as roots and tubers.

According to this theory, complex hierarchy did not emerge among hunter-gatherers because hunter-gatherers essentially live from hand-to-mouth, with little that can be expropriated from them to feed a would-be elite. [Continue reading…]