Chris Hedges gave this talk Sunday night in New York City at a protest denouncing the 11th anniversary of the war in Afghanistan. The event, at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, was led by Veterans for Peace.

Many of us who are here carry within us death. The smell of decayed and bloated corpses. The cries of the wounded. The shrieks of children. The sound of gunfire. The deafening blasts. The fear. The stench of cordite. The humiliation that comes when you surrender to terror and beg for life. The loss of comrades and friends. And then the aftermath. The long alienation. The numbness. The nightmares. The lack of sleep. The inability to connect to all living things, even to those we love the most. The regret. The repugnant lies mouthed around us about honor and heroism and glory. The absurdity. The waste. The futility.

It is only the maimed that finally know war. And we are the maimed. We are the broken and the lame. We ask for forgiveness. We seek redemption. We carry on our backs this awful cross of death, for the essence of war is death, and the weight of it digs into our shoulders and eats away at our souls. We drag it through life, up hills and down hills, along the roads, into the most intimate recesses of our lives. It never leaves us. Those who know us best know that there is something unspeakable and evil many of us harbor within us. This evil is intimate. It is personal. We do not speak its name. It is the evil of things done and things left undone. It is the evil of war.

We do not speak of war. War is captured only in the long, vacant stares, in the silences, in the trembling fingers, in the memories most of us keep buried deep within us, in the tears.

It is impossible to portray war. Narratives, even anti-war narratives, make the irrational rational. They make the incomprehensible comprehensible. They make the illogical logical. They make the despicable beautiful. All words and images, all discussions, all films, all evocations of war, good or bad, are an obscenity. There is nothing to say. [Continue reading…]

Category Archives: military affairs

Video: War is hell — The Naked and the Dead

U.S. troops are killing themselves at fastest pace since nation began a decade of war

The Associated Press reports: Suicides are surging among America’s troops, averaging nearly one a day this year — the fastest pace in the nation’s decade of war.

The 154 suicides for active-duty troops in the first 155 days of the year far outdistance the U.S. forces killed in action in Afghanistan — about 50 percent more — according to Pentagon statistics obtained by The Associated Press.

The numbers reflect a military burdened with wartime demands from Iraq and Afghanistan that have taken a greater toll than foreseen a decade ago. The military also is struggling with increased sexual assaults, alcohol abuse, domestic violence and other misbehavior.

Because suicides had leveled off in 2010 and 2011, this year’s upswing has caught some officials by surprise.

The reasons for the increase are not fully understood. Among explanations, studies have pointed to combat exposure, post-traumatic stress, misuse of prescription medications and personal financial problems. Army data suggest soldiers with multiple combat tours are at greater risk of committing suicide, although a substantial proportion of Army suicides are committed by soldiers who never deployed.

The unpopular war in Afghanistan is winding down with the last combat troops scheduled to leave at the end of 2014. But this year has seen record numbers of soldiers being killed by Afghan troops, and there also have been several scandals involving U.S. troop misconduct.

The 2012 active-duty suicide total of 154 through June 3 compares to 130 in the same period last year, an 18 percent increase. And it’s more than the 136.2 suicides that the Pentagon had projected for this period based on the trend from 2001-2011. This year’s January-May total is up 25 percent from two years ago, and it is 16 percent ahead of the pace for 2009, which ended with the highest yearly total thus far.

Suicide totals have exceeded U.S. combat deaths in Afghanistan in earlier periods, including for the full years 2008 and 2009.

Paul Fussell: The culture of war

Memorial Day: Among post-9/11 veterans, deepening antiwar sentiment

Here are some numbers to remember this Memorial Day: Although only 1 percent of Americans have served during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, former service members represent 20 percent of suicides in the United States — 18 veterans kill themselves everyday. Close to a million veterans currently have pending disability claims.

Christian Science Monitor reports: Despite the end of the Iraq war and the scheduled drawdown in Afghanistan, this Memorial Day arrives against a backdrop of deepening – and some say more troublesome – antiwar sentiment among military veterans.

One of the most vivid and replayed images of protesters at the NATO summit last weekend in Chicago was a group of some 40 vets lined up to toss their war medals over the chain link fence to protest what former naval officer Leah Bolger calls “the illegal wars of both NATO and America.”

According to a recent Pew Research Center study, 33 percent of post-9/11 veterans say that neither the war in Iraq nor in Afghanistan “were worth the cost,” and this among a highly motivated cohort who chose to serve.

What this means, says retired US Army Col. Ann Wright, who resigned from a State Department post in 2006 over US policies in Iraq, is that there is a widening gap between the government, military policies, and the soldiers that carry them out.

“Military personnel know America will always have a military, but there is growing concern over the way it is being used,” says the 29-year veteran, adding that an increasing list of concerns include “the use of torture, illegal detentions, and both soldiers and the public being lied to about the actual reasons for going into combat.”

Veterans and brain disease

Nicholas Kristof writes: He was a 27-year-old former Marine, struggling to adjust to civilian life after two tours in Iraq. Once an A student, he now found himself unable to remember conversations, dates and routine bits of daily life. He became irritable, snapped at his children and withdrew from his family. He and his wife began divorce proceedings.

This young man took to alcohol, and a drunken car crash cost him his driver’s license. The Department of Veterans Affairs diagnosed him with post-traumatic stress disorder, or P.T.S.D. When his parents hadn’t heard from him in two days, they asked the police to check on him. The officers found his body; he had hanged himself with a belt.

That story is devastatingly common, but the autopsy of this young man’s brain may have been historic. It revealed something startling that may shed light on the epidemic of suicides and other troubles experienced by veterans of wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

His brain had been physically changed by a disease called chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or C.T.E. That’s a degenerative condition best-known for affecting boxers, football players and other athletes who endure repeated blows to the head.

In people with C.T.E., an abnormal form of a protein accumulates and eventually destroys cells throughout the brain, including the frontal and temporal lobes. Those are areas that regulate impulse control, judgment, multitasking, memory and emotions.

That Marine was the first Iraq veteran found to have C.T.E., but experts have since autopsied a dozen or more other veterans’ brains and have repeatedly found C.T.E. The findings raise a critical question: Could blasts from bombs or grenades have a catastrophic impact similar to those of repeated concussions in sports, and could the rash of suicides among young veterans be a result? [Continue reading…]

Drones, Asia and cyber war

The future of the U.S. military

Turning war into ‘peace’ by deleting and replacing memories

Imagine soldiers who couldn’t be traumatized; who could engage in the worst imaginable brutality and not only remember nothing, but remember something else, completely benign. That might just sound like dystopian science fiction, but ongoing research is laying the foundations to turn this into reality.

Alison Winter, author of Memory: Fragments of a Modern History, from which the following is adapted, writes:

The first speculative steps are now being taken in an attempt to develop techniques of what is being called “therapeutic forgetting.” Military veterans suffering from PTSD are currently serving as subjects in research projects on using propranolol to mitigate the effects of wartime trauma. Some veterans’ advocates criticize the project because they see it as a “metaphor” for how the “administration, Defense Department, and Veterans Affairs officials, not to mention many Americans, are approaching the problem of war trauma during the Iraq experience.”

The argument is that terrible combat experiences are “part of a soldier’s life” and are “embedded in our national psyche, too,” and that these treatments reflect an illegitimate wish to forget the pain suffered by war veterans. Tara McKelvey, who researched veterans’ attitudes to the research project, quoted one veteran as disapproving of the project on the grounds that “problems have to be dealt with.” This comment came from a veteran who spends time “helping other veterans deal with their ghosts, and he gives talks to high school and college students about war.” McKelvey’s informant felt that the definition of who he was “comes from remembering the pain and dealing with it — not from trying to forget it.” The assumption here is that treating the pain of war pharmacologically is equivalent to minimizing, discounting, disrespecting and ultimately setting aside altogether the sacrifices made by veterans, and by society itself. People who objected to the possibility of altering emotional memories with drugs were concerned that this amounted to avoiding one’s true problems instead of “dealing” with them. An artificial record of the individual past would by the same token contribute to a skewed collective memory of the costs of war.

In addition to the work with veterans, there have been pilot studies with civilians in emergency rooms. In 2002, psychiatrist Roger Pitman of Harvard took a group of 31 volunteers from the emergency rooms at Massachusetts General Hospital, all people who had suffered some traumatic event, and for 10 days treated some with a placebo and the rest with propranolol [a beta blocker]. Those who received propranolol later had no stressful physical response to reminders of the original trauma, while almost half of the others did. Should those E.R. patients have been worried about the possible legal implications of taking the drug? Could one claim to be as good a witness once one’s memory had been altered by propranolol? And in a civil suit, could the defense argue that less harm had been done, since the plaintiff had avoided much of the emotional damage that an undrugged victim would have suffered? Attorneys did indeed ask about the implications for witness testimony, damages, and more generally, a devaluation of harm to victims of crime. One legal scholar framed this as a choice between protecting memory “authenticity” (a category he used with some skepticism) and “freedom of memory.” Protecting “authenticity” could not be done without sacrificing our freedom to control our own minds, including our acts of recall.

The anxiety provoked by the idea of “memory dampening” is so intriguing that even the President’s Council on Bioethics, convened by President George W. Bush in his first term, thought the issue important enough to reflect on it alongside discussions of cloning and stem-cell research. Editing memories could “disconnect people from reality or their true selves,” the council warned. While it did not give a definition of “selfhood,” it did give examples of how such techniques could warp us by “falsifying our perception and understanding of the world.” The potential technique “risks making shameful acts seem less shameful, or terrible acts less terrible, than they really are.”

Meanwhile, David DiSalvo notes ten brain science studies from 2011 including this:

Brain Implant Enables Memories to be Recorded and Played Back

Neural prosthetics had a big year in 2011, and no development in this area was bigger than an implant designed to record and replay memories.

Researchers had a group of rats with the implant perform a simply memory task: get a drink of water by hitting one lever in a cage, then—after a distraction—hitting another. They had to remember which lever they’d already pushed to know which one to push the second time. As the rats did this memory task, electrodes in the implants recorded signals between two areas of their brains involved in storing new information in long-term memory.

The researchers then gave the rats a drug that kept those brain areas from communicating. The rats still knew they had to press one lever then the other to get water, but couldn’t remember which lever they’d already pressed. When researchers played back the neural signals they’d recorded earlier via the implants, the rats again remembered which lever they had hit, and pressed the other one. When researchers played back the signals in rats not on the drug (thus amplifying their normal memory) the rats made fewer mistakes and remembered which lever they’d pressed even longer.

The bottom line: This is ground-level research demonstrating that neural signals involved in memory can be recorded and replayed. Progress from rats to humans will take many years, but even knowing that it’s plausible is remarkable.

How they learned to hate the bomb

A New York Times review of The Partnership: Five Cold Warriors and Their Quest to Ban the Bomb: On the day after a nuclear bomb annihilates Washington, New Delhi, Islamabad, Seoul, Tel Aviv or Moscow, vaporizing and burning to death hundreds of thousands of people, our present complacency about nuclear proliferation will look like daylight madness. Even the chilliest of realists have shuddered at our capability for radioactive massacre. In 1977, the strategist George F. Kennan declared, “No one is good enough, wise enough, steady enough, to have control over the volume of explosives that now rest in the hands of this country.” Nuclear arms, he concluded, “shouldn’t exist at all.”

Philip Taubman’s fascinating, haunting book, “The Partnership,” is about the drive to abolish nuclear weapons — and, implicitly, about why it will probably fail. Taubman, a former reporter and editor for The New York Times, tells the stories of five American national security mandarins who, in the twilight of their illustrious careers, stunned their peers by campaigning to scrap all nuclear arms. They are not exactly pacifist hippies: Henry A. Kissinger and George P. Shultz, Republican secretaries of state; William J. Perry, a Democratic secretary of defense; Sam Nunn, a Democrat who had been chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee; and Sidney D. Drell, an influential Stanford physicist. Their continuing activism, Taubman writes, “has induced sitting presidents and foreign ministers to embrace ideas not long ago ridiculed as radical and reckless,” and has “powerfully influenced Obama,” who advocates a world without nuclear weapons.

These five men had done much to foster a nuclearized world, and had prospered for their contributions to its infernal machinery. Much of “The Partnership” consists of eerie tales of the atomic cold war, charting the upward progress of these grandees. When they broke ranks, Taubman writes, “it was roughly equivalent to John D. Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie, J. P. Morgan and Jay Gould calling for the demise of capitalism.”

The core of the book is Shultz, the group’s “undeclared leader” and its “most committed” member. Taubman affectionately writes that he “radiated probity, pragmatism and Republicanism.” “I had never learned to love the bomb,” Shultz says. At the Reykjavik summit in October 1986, as President Reagan’s secretary of state, he had a heartbreaking brush with nuclear abolition. (Taubman was there as a reporter.) The American and Soviet chiefs came close to a historic deal to eliminate all their nuclear weapons. But the agreement foundered over Reagan’s “quixotic quest to build a missile shield,” which Mikhail Gorbachev rejected. Shultz, skeptical about the missile defense project, was disappointed.

How many U.S. soldiers were wounded in Iraq? Guess again

Dan Froomkin writes: Reports about the end of the war in Iraq routinely describe the toll on the U.S. military the way the Pentagon does [PDF]: 4,487 dead, and 32,226 wounded.

The death count is accurate. But the wounded figure wildly understates the number of American servicemembers who have come back from Iraq less than whole.

The true number of military personnel injured over the course of our nine-year-long fiasco in Iraq is in the hundreds of thousands — maybe even more than half a million — if you take into account all the men and women who returned from their deployments with traumatic brain injuries, post-traumatic stress, depression, hearing loss, breathing disorders, diseases, and other long-term health problems.

We don’t have anything close to an exact number, however, because nobody’s been keeping track.

The much-cited Defense Department figure comes from its tally of “wounded in action” [PDF] — a narrowly-tailored category that only includes casualties during combat operations who have “incurred an injury due to an external agent or cause.” That generally means they needed immediate medical treatment after having been shot or blown up. Explicitly excluded from that category are “injuries or death due to the elements, self-inflicted wounds, combat fatigue” — along with cumulative psychological and physiological strain or many of the other wounds, maladies and losses that are most common among Iraq veterans.

The “wounded in action” category is relatively consistent, historically, so it’s still useful as a point of comparison to previous wars. But there is no central repository of data regarding these other, sometimes grievous, harms. We just have a few data points here and there that indicate the magnitude. [Continue reading…]

A look at the US military’s Joint Special Operations Command

Dana Priest and William M. Arkin write:

Two presidents and three secretaries of defense routinely have asked JSOC to mount intelligence-gathering missions and lethal raids, mostly in Iraq and Afghanistan, but also in countries with which the United States was not at war, including Yemen, Pakistan, Somalia, the Philippines, Nigeria and Syria.

“The CIA doesn’t have the size or the authority to do some of the things we can do,” said one JSOC operator.

The president has also given JSOC the rare authority to select individuals for its kill list — and then to kill, rather than capture, them. Critics charge that this individual man-hunting mission amounts to assassination, a practice prohibited by U.S. law. JSOC’s list is not usually coordinated with the CIA, which maintains a similar, but shorter roster of names.

Created in 1980 but reinvented in recent years, JSOC has grown from 1,800 troops prior to 9/11 to as many as 25,000, a number that fluctuates according to its mission. It has its own intelligence division, its own drones and reconnaissance planes, even its own dedicated satellites. It also has its own cyberwarriors, who, on Sept. 11, 2008, shut down every jihadist Web site they knew.

Obscurity has been one of the unit’s hallmarks. When JSOC officers are working in civilian government agencies or U.S. embassies abroad, which they do often, they dispense with uniforms, unlike their other military comrades. In combat, they wear no name or rank identifiers. They have hidden behind various nicknames: the Secret Army of Northern Virginia, Task Force Green, Task Force 11, Task Force 121. JSOC leaders almost never speak in public. They have no unclassified Web site.

Despite the secrecy, JSOC is not permitted to carry out covert action like the CIA. Covert action, in which the U.S. role is to be kept hidden, requires a presidential finding and congressional notification. Many national security officials, however, say JSOC’s operations are so similar to the CIA’s that they amount to covert action. The unit takes its orders directly from the president or the secretary of defense and is managed and overseen by a military-only chain of command.

Army vet with PTSD sought the treatment he needed by taking hostages — but got jail instead

Stars and Stripes reports:

“I’m Robert Anthony Quinones, but my friends call me Q,” the former Army sergeant told the ER medic as he pointed a 9 mm handgun at the medic’s head.

“Can I call you Q?” asked the nervous medic, Sgt. Hubert Henson.

“Yeah.”

“OK,” Henson replied. “Well, Q, if you put the gun away, I can take you upstairs to behavioral health to get help.”

Quinones scoffed, instead ordering Henson to carry his three bags: a shaving kit, a duffel stuffed with clothes and books, and a backpack bulging with two assault rifles, a .38-caliber handgun, knives and ammunition.

Fifteen months of carnage in Iraq had left the 29-year-old debilitated by post-traumatic stress disorder. But despite his doctor’s urgent recommendation, the Army failed to send him to a Warrior Transition Unit for help. The best the Department of Veterans Affairs could offer was 10-minute therapy sessions — via videoconference.

So, early on Labor Day morning last year, after topping off a night of drinking with a handful of sleeping pills, Quinones barged into Fort Stewart’s hospital, forced his way to the third-floor psychiatric ward and held three soldiers hostage, demanding better mental health treatment.

“I’ve done it the Army’s way,” Quinones told Henson. “We’re going to do it my way now.”

The standoff ended after two hours without any injuries, but Quinones’ problems were only beginning.

While in custody, Quinones threatened the lives of President Barack Obama and former President Bill Clinton, making his already bleak situation worse. Now he’s sitting in a jail cell awaiting his fate on a litany of federal charges while a court sorts out whether he should be prosecuted or committed.

Quinones’ story is one of an ordinary soldier who went off to war, came home broken, and then went over the edge after the government didn’t do enough to fix him. Even the three soldiers held at the point of Quinones’ guns today express more empathy than animosity for their captor.

To them, what Quinones did that day was the ultimate cry for help.

Hold Israel accountable with Leahy law

Josh Ruebner writes:

Apologists for Israeli occupation and apartheid claim that advocates for holding Israel accountable for its human rights abuses of Palestinians are “singling Israel out for extra scrutiny” or “holding Israel to a higher standard than other countries.”

Yet, ironically, Israel’s supporters also claim that U.S. military aid to Israel is sacrosanct and, unlike every other governmental program on the chopping block these days, cannot be questioned due to the “special U.S.-Israeli relationship.” Dan Carle, a spokesperson for Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.), has noted correctly that you cannot have your cake and eat it too.

In response to an article in the Israeli newspaper Ha’aretz suggesting that the Vermont Senator will attempt to apply sanctions to certain units of the Israeli military for human rights violations, Carle explained that “the [Leahy] law applies to U.S. aid to foreign security forces around the globe and is intended to be applied consistently across the spectrum of U.S. military aid abroad. Under the law the State Department is responsible for evaluations and enforcement decisions and over the years Senator Leahy has pressed for faithful and consistent application of the law.”

The possibility of Senator Leahy consistently applying this eponymous legislation and holding Israel to the exact same standard as every other country has Israeli Defense Minister Ehud Barak, whose office may have leaked the story in an effort to kill the initiative, in a tizzy.

The “Leahy Law,” as it is commonly known, prohibits the United States from providing any weapons or training to “any unit of the security forces of a foreign country if the Secretary of State has credible evidence that such unit has committed gross violations of human rights.” In the past, this law has been invoked to curtail military aid to countries as diverse as Indonesia, Colombia, Pakistan, and the Philippines. Along with other provisions in the Foreign Assistance Act, of which it is a part, and the Arms Export Control Act, it forms the basis of an across-the-board policy that is supposed to ensure that U.S. assistance does not contribute to human rights abuses.

Ha’aretz reports that the Senator is looking to invoke this prohibition regarding “Israel Navy’s Shayetet 13 unit, the undercover Duvdevan unit and the Israel Air Force’s Shaldag unit.” The inclusion of specific units in the story may indicate that Leahy already has findings from the Secretary of State that these Israeli military units have committed human rights abuses.

If so, then this could be a much-overdue watershed in holding accountable Israel, the largest recipient of U.S. military aid, for its gross misuse of U.S. weapons to commit systematic human rights abuses of Palestinians living under Israel’s illegal 44-year military occupation of the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and Gaza Strip.

Suicide: For some South Florida veterans, it’s the biggest threat

The Los Angeles Times reports:

During 27 years in the Army, Ben Mericle survived tours in Bosnia, the Gulf War and Iraq. But it was only after coming home to West Palm Beach in 2006 that he came close to dying — by his own hand.

“I just wanted to disappear,” said Mericle, 50, recalling the many times he considered mixing a fatal cocktail from his prescribed medications and the prodigious amounts of alcohol he was drinking.

“I had so much anger. I wasn’t sleeping, had nightmares when I did, flashbacks. It was survivor’s guilt.”

Some do not survive, leading Adm. Mike Mullen, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, to identify the “emergency issue” facing the American military: a rise in the number of suicides.

On Wednesday, President Obama announced he will reverse a longstanding policy and begin sending condolence letters to the families of service members who commit suicide while deployed to a combat zone.

“This decision was made after a difficult and exhaustive review of the former policy, and I did not make it lightly,” Obama said in a statement. “This issue is emotional, painful, and complicated, but these Americans served our nation bravely. They didn’t die because they were weak. And the fact that they didn’t get the help they needed must change.”

Last year, 301 active-duty Army, Reserve and National Guard soldiers committed suicide, compared with 242 in 2009, according to Army figures.

How Boeing ripped off American taxpayers

The Project on Government Oversight reports:

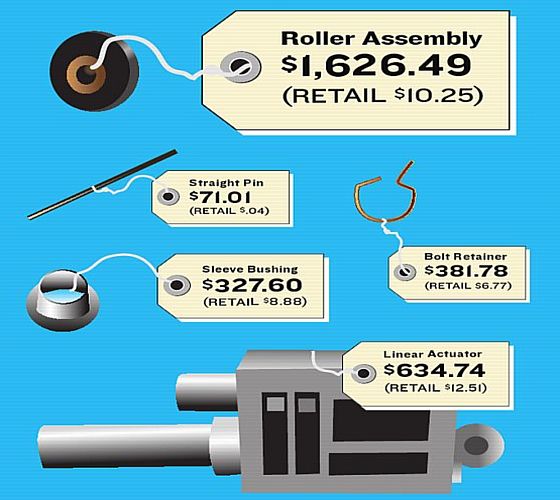

$644.75 for a small gear smaller than a dime that sells for $12.51: more than a 5,100 percent increase in price. $1,678.61 for another tiny part, also smaller than a dime, that could have been bought within DoD for $7.71: a 21,000 percent increase. $71.01 for a straight, thin metal pin that DoD had on hand, unused by the tens of thousands, for 4 cents: an increase of over 177,000 percent.

Taxpayers were massively overcharged in dozens of transactions between the Army and Boeing for helicopter spare parts, according to a full, unredacted Department of Defense Office of Inspector General (DoD OIG) audit that POGO is making public for the first time. The overcharges range from 33.3 percent to 177,475 percent for mundane parts, resulting in millions of dollars in overspending.

The May 3, 2011, unclassified “For Official Use Only” report is 142 pages. Prior to POGO’s publication of the full report, the only publicly available version was a 3-page “results in brief” on the DoD OIG’s website, first reported by Bloomberg News. The findings in the results in brief, while shocking on their own, pale in comparison to the detail contained within the full report. The DoD OIG scrutinized Army Aviation and Missile Life Cycle Management Command (AMCOM) transactions with Boeing that were in support of the Corpus Christi Army Depot (CCAD) in Texas. The audit focused on 24 “high-dollar” parts. Boeing had won two sole-source contracts (the second was a follow-on contract awarded last year) to provide the Army with logistics support—one of those support functions meant Boeing would help buy and/or make spare parts for the Army—for two weapons systems: the Boeing AH-64 Apache and Boeing CH-47 Chinook helicopters.

Overall, for 18 of 24 parts reviewed, the DoD OIG found that the Army should have only paid $10 million instead of the nearly $23 million it paid to Boeing for these parts—overall, taxpayers were overpaying 131.5 percent above “fair and reasonable” prices. The audit says Boeing needs to refund approximately $13 million Boeing overcharged for the 18 parts. Boeing had, as of the issuance of the audit, refunded approximately $1.3 million after the DoD OIG issued the draft version of its report. Boeing also provided a “credit” to the Army for another part for $324,616. The Army has resisted obtaining refunds worth several million dollars on some of the overpriced spare parts, in opposition to the DoD IG’s recommendations. For instance, one of the IG’s recommendations was that the Army should request a $6 million refund from Boeing for charging the Army for higher subcontractor prices even though Boeing negotiated lower prices from those subcontractors. In response, the Army said that “there is no justification to request a refund.”

In calculating what it says the Army should have paid, the DoD OIG assumed Boeing reasonably should charge a 34 percent surcharge fee for overhead, general and administrative costs, and profit, according to the audit report.

Above and beyond what the DoD OIG viewed as fair and reasonable (including the 34 percent surcharge), Boeing’s average overcharges to the Army for these 18 parts range from 33.3 percent to as much as 5,434 percent, based on the DoD OIG’s analysis.

What is even more shocking is the difference in prices the Army would have paid if it procured many of these parts directly from the Defense Logistics Agency (DLA) and from the Army’s own procurement offices, the audit shows. The largest percentage differences cited in the DoD OIG report—such as the 177,475 percent example (which is not among the 18 parts the report focuses on)—compare DLA unit prices to Boeing unit prices.

Meanwhile, NPR reports:

The amount the U.S. military spends annually on air conditioning in Iraq and Afghanistan: $20.2 billion.

That’s more than NASA’s budget. It’s more than BP has paid so far for damage during the Gulf oil spill. It’s what the G-8 has pledged to help foster new democracies in Egypt and Tunisia.

“When you consider the cost to deliver the fuel to some of the most isolated places in the world — escorting, command and control, medevac support — when you throw all that infrastructure in, we’re talking over $20 billion,” Steven Anderson tells weekends on All Things Considered guest host Rachel Martin. Anderson is a retired brigadier general who served as Gen. David Patreaus’ chief logistician in Iraq.

Cyber combat: act of war

The Wall Street Journal reports:

The Pentagon has concluded that computer sabotage coming from another country can constitute an act of war, a finding that for the first time opens the door for the U.S. to respond using traditional military force.

The Pentagon’s first formal cyber strategy, unclassified portions of which are expected to become public next month, represents an early attempt to grapple with a changing world in which a hacker could pose as significant a threat to U.S. nuclear reactors, subways or pipelines as a hostile country’s military.

In part, the Pentagon intends its plan as a warning to potential adversaries of the consequences of attacking the U.S. in this way. “If you shut down our power grid, maybe we will put a missile down one of your smokestacks,” said a military official.

Recent attacks on the Pentagon’s own systems—as well as the sabotaging of Iran’s nuclear program via the Stuxnet computer worm—have given new urgency to U.S. efforts to develop a more formalized approach to cyber attacks. A key moment occurred in 2008, when at least one U.S. military computer system was penetrated. This weekend Lockheed Martin, a major military contractor, acknowledged that it had been the victim of an infiltration, while playing down its impact.

The Associated Press reports:

This cyber attack didn’t go after people playing war games on their PlayStations. It targeted a company that helps the U.S. military do the real thing.

Lockheed Martin says it was the recent target of a “significant and tenacious” hack, although the defense contractor and the Department of Homeland Security insist the attack was thwarted before any critical data was stolen. The effort highlighted the fact that some hackers, including many working for foreign governments, set their sights on information far more devastating than credit card numbers.

Information security experts say a rash of cyber attacks this year — including a massive security breach at Sony Corp. last month that affected millions of PlayStation users — has emboldened hackers and made them more willing to pursue sensitive information.

“2011 has really lit up the boards in terms of data breaches,” said Josh Shaul, chief technology officer at Application Security, a New York-based company that is one of the largest database security software makers. “The list of targets just grows and grows.”

How America screws its soldiers

Andrew J. Bacevich writes:

Riders on Boston subways and trolleys are accustomed to seeing placards that advertise research being conducted at the city’s many teaching hospitals. One that recently caught my eye, announcing an experimental “behavioral treatment,” posed this question to potential subjects: “Are you in the U.S. military or a veteran disturbed by terrible things you have experienced?”

Just below the question, someone had scrawled this riposte in blue ink: “Thank God for these Men and Women. USA all the way.”

Here on a 30 x 36 inch piece of cardboard was the distilled essence of the present-day relationship between the American people and their military. In the eyes of citizens, the American soldier has a dual identity: as hero but also as victim. As victims—Wounded Warriors —soldiers deserve the best care money can buy; hence, the emphasis being paid to issues like PTSD. As heroes, those who serve and sacrifice embody the virtues that underwrite American greatness. They therefore merit unstinting admiration.

Whatever practical meaning the slogan “support the troops” may possess, it lays here: in praise expressed for those choosing to wear the uniform, and in assistance made available to those who suffer as a consequence of that choice.

From the perspective of the American people, the principal attribute of this relationship is that it entails no real obligations or responsibilities. Face it: It costs us nothing yet enables us to feel good about ourselves. In an unmerited act of self-forgiveness, we thereby expunge the sin of the Vietnam era when opposition to an unpopular war found at least some Americans venting their unhappiness on the soldiers sent to fight it. The homeward-bound G.I. spat upon by spoiled and impudent student activists may be an urban legend, but the fiction persists and has long since trumped reality.