Peter Rothberg writes: More than six weeks into the occupation of Zuccotti Park by a ragtag band of a few hundred anti-corporate activists, Occupy Wall Street has quickly grown into an international movement and potent symbol of popular outrage over the widening gaps between rich and poor and the way that government has been hijacked to transfer wealth upwards to the one percent.

The movement’s message has also gone surprisingly mainstream, as my colleague Katha Pollitt detailed in her latest Nation column explaining the OWS’s appeal and why unlikely suspects like Deepak Chopra and Suze Orman have jumped on the Occupy Wall Street wagon.

After the first week of protests, I wrote a brief guide featuring some tips on how to help the then-burgeoning movement. Now, I’ve updated that primer with new suggestions and specific tips for supporting some of the many regional Occupy actions that have recently been established.

How to Support Occupy Wall Street

1. Go to Liberty Plaza to join those that Occupy Wall Street if you can. This is the epicenter of the movement and the inspiration for what’s happening across the country. Carpools are being arranged va this Facebook group.

2. Send non-perishable food, books, magazines, coffee, tea bags, aspirin, blankets and socks to the UPS Store, c/o Occupy Wall Street, 118A Fulton St, #205, NY, NY 10038.

3. Have pizza delivered to the protestors at Liberty Plaza. Call Majestic Pizza Corp at 212-349-4046 and have your credit card ready.

4. Tell the nation’s mayors to respect the people’s right to free assembly. The eviction of the Liberty Square occupation on Wall Street was averted by massive public protest from those in the square and from others. When you learn that an occupation is threatened, please use this list, courtesy of activist Cryn Johannsen, to find the mayor’s phone number and ask him or her to let the protestors protest.

5. Circulate word of Occupy College’s national series of Teach-ins on November 2nd and 3rd. More than 100 schools have signed on to date.

6. Donate to Occupy Wall Street through its website.

7. Get informed and let your friends and family know what’s happening on Wall Street, what the movement is about, and why you care. [Continue reading…]

Category Archives: Occupy Wall Street

The radical power of just showing up

Jillian Schwedler writes: The Arab Spring initiated a jarring series of events in 2011 that illustrate the radical political possibilities of just being present. When the regime won’t listen, when being heard as an individual isn’t really a viable option, simply standing together and being seen can be profoundly political and empowering.

But will just “being there” really bring significant change?

Revolutions never happen overnight. They result from accumulations of dozens, even hundreds of moments, often stretching over a period of years, that make possible the ruptures that emerge when vast numbers of people begin to imagine, and then to demand, an alternative to their living conditions. We have been seeing these moments over the past year, first in the Middle East but then spreading to England, Brazil, Spain, Great Britain, the United States, and elsewhere. In this sense, we are experiencing a revolutionary moment in which the popular perception of what is possible has indisputably shifted in a way unseen on a global scale since 1968.

This moment is revolutionary, even though revolutions are not imminent everywhere. People around the globe are simultaneously imagining alternatives to the conditions under which they live, and they recognise such movements taking place elsewhere and feel a connection, a kinship, with other who are taking to the streets and reclaiming public spaces. For some, the imagined future entails a fundamental change in the structures of government; for others, it entails an alternative to the economic status quo. But for all of them, often for the first time in generations, an alternative future feels possible and tangible rather than fantastical.

Revolutionary moments don’t always foster revolutions, of course. Political revolutions are only possible when the repressive security apparatuses that defend the regime – the army, the police, and other agencies of force – become divided. When armies divide, when some leaders and their troops defect, that is when a revolution becomes possible. But even this does not mean that a revolution will be successful. It can lead to a regime change, even a rapid or peaceful one, but more often it can lead to a bloody, protracted civil war. But for many of the citizens – albeit not for all of them – sustained bloodshed is preferable because it keeps alive the hope that an alternative future is finally within grasp. Witnessing people choose these bloody moments of possibility over the (sometimes bloody) status quo has a dramatic impact. If they can do it-when the obstacles they have successfully overcome were far more daunting than the ones we face – why are we acquiescing to the repressive conditions that limit the possibilities of our own lives?

Although many hope to dismiss its potential, Occupy Wall Street represents just such a revolutionary moment. It is a politics of refusal because of its strong and sustained rejection of a system that dismisses the economic struggles of most of the people on the globe. It is a refusal to feel helpless and powerless in the face of economic policies that favour banks and corporations at the expense of flesh and blood. That refusal has been manifest in the retaking of public spaces, an outpouring of people into places where their frustrations and grievances become visible. Merely standing together in public can be a radical political act because governments around the world seek to control how public spaces are used, preserving them for certain kinds of loyal and conforming citizens. “Undesirables” – the homeless, the punks, skateboarders, graffiti artists, groups of young men, and of course protesters who question the prevailing political and economic policies – must all be cleared from those spaces, sometimes at high costs. Who is welcome? Nuclear families, particularly if they are spending money.

Should banks be a public utility?

The class war has begun

Frank Rich writes: During the death throes of Herbert Hoover’s presidency in June 1932, desperate bands of men traveled to Washington and set up camp within view of the Capitol. The first contingent journeyed all the way from Portland, Oregon, but others soon converged from all over—alone, in groups, with families—until their main Hooverville on the Anacostia River’s fetid mudflats swelled to a population as high as 20,000. The men, World War I veterans who could not find jobs, became known as the Bonus Army—for the modest government bonus they were owed for their service. Under a law passed in 1924, they had been awarded roughly $1,000 each, to be collected in 1945 or at death, whichever came first. But they didn’t want to wait any longer for their pre–New Deal entitlement—especially given that Congress had bailed out big business with the creation of a Reconstruction Finance Corporation earlier in its session. Father Charles Coughlin, the populist “Radio Priest” who became a phenomenon for railing against “greedy bankers and financiers,” framed Washington’s double standard this way: “If the government can pay $2 billion to the bankers and the railroads, why cannot it pay the $2 billion to the soldiers?”

The echoes of our own Great Recession do not end there. Both parties were alarmed by this motley assemblage and its political rallies; the Secret Service infiltrated its ranks to root out radicals. But a good Communist was hard to find. The men were mostly middle-class, patriotic Americans. They kept their improvised hovels clean and maintained small gardens. Even so, good behavior by the Bonus Army did not prevent the U.S. Army’s hotheaded chief of staff, General Douglas MacArthur, from summoning an overwhelming force to evict it from Pennsylvania Avenue late that July. After assaulting the veterans and thousands of onlookers with tear gas, MacArthur’s troops crossed the bridge and burned down the encampment. The general had acted against Hoover’s wishes, but the president expressed satisfaction afterward that the government had dispatched “a mob”—albeit at the cost of killing two of the demonstrators. The public had another take. When graphic newsreels of the riotous mêlée fanned out to the nation’s movie theaters, audiences booed MacArthur and his troops, not the men down on their luck. Even the mining heiress Evalyn Walsh McLean, the owner of the Hope diamond and wife of the proprietor of the Washington Post, professed solidarity with the “mob” that had occupied the nation’s capital.

The Great Depression was then nearly three years old, with FDR still in the wings and some of the worst deprivation and unrest yet to come. Three years after our own crash, we do not have the benefit of historical omniscience to know where 2011 is on the time line of America’s deepest bout of economic distress since that era. (The White House, you may recall, rolled out “recovery summer” sixteen months ago.) We don’t know if our current president will end up being viewed more like Hoover or FDR. We don’t know whether Occupy Wall Street and its proliferating satellites will spiral into larger and more violent confrontations, disperse in cold weather, prove a footnote to our narrative, or be the seeds of something big.

What’s as intriguing as Occupy Wall Street itself is that once again our Establishment, left, right, and center, did not see the wave coming or understand what it meant as it broke. Maybe it’s just human nature and the power of denial, or maybe it’s a stubborn strain of all-American optimism, but at each aftershock since the fall of Lehman Brothers, those at the top have preferred not to see what they didn’t want to see. And so for the first three weeks, the protests were alternately ignored, patronized, dismissed, and insulted by politicians and the mainstream news media as a neo-Woodstock for wannabe collegiate rebels without a cause—and not just in Fox-land. CNN’s new prime-time hopeful, Erin Burnett, ridiculed the protesters as bongo-playing know-nothings; a dispatch in The New Republic called them “an unfocused rabble of ragtag discontents.” Those who did express sympathy for Occupy Wall Street tended to pat it on the head before going on to fault it for being leaderless, disorganized, and inchoate in its agenda.

Despite such dismissals, the movement, abetted by made-for-YouTube confrontations with police, started to connect with the mass public much as the Bonus Army did with a newsreel audience. The week after a Wall Street Journal editorial claimed that “no one seems to care very much” about the “collection of ne’er-do-wells” congregating in Zuccotti Park, the paper released its own poll, in collaboration with NBC News, finding that 37 percent of Americans supported the protesters, 25 percent had no opinion, and just 18 percent opposed them. The approval numbers for Occupy Wall Street published in Time and Reuters were even higher—hitting 54 percent in Time. Apparently some of those dopey kids, staggering under student loans and bereft of job prospects, have lots of parents and friends of all ages who understand exactly what they’re talking about.

Wall Street firms spy on protesters in tax-funded center

Pam Martens writes: Wall Street’s audacity to corrupt knows no bounds and the cooptation of government by the 1 per cent knows no limits. How else to explain $150 million of taxpayer money going to equip a government facility in lower Manhattan where Wall Street firms, serially charged with corruption, get to sit alongside the New York Police Department and spy on law abiding citizens.

According to newly unearthed documents, the planning for this high tech facility on lower Broadway dates back six years. In correspondence from 2005 that rests quietly in the Securities and Exchange Commission’s archives, NYPD Commissioner Raymond Kelly promised Edward Forst, a Goldman Sachs’ Executive Vice President at the time, that the NYPD “is committed to the development and implementation of a comprehensive security plan for Lower Manhattan…One component of the plan will be a centralized coordination center that will provide space for full-time, on site representation from Goldman Sachs and other stakeholders.”

At the time, Goldman Sachs was in the process of extracting concessions from New York City just short of the Mayor’s first born in exchange for constructing its new headquarters building at 200 West Street, adjacent to the World Financial Center and in the general area of where the new World Trade Center complex would be built. According to the 2005 documents, Goldman’s deal included $1.65 billion in Liberty Bonds, up to $160 million in sales tax abatements for construction materials and tenant furnishings, and the deal-breaker requirement that a security plan that gave it a seat at the NYPD’s Coordination Center would be in place by no later than December 31, 2009.

The surveillance plan became known as the Lower Manhattan Security Initiative and the facility was eventually dubbed the Lower Manhattan Security Coordination Center. It operates round-the-clock. Under the imprimatur of the largest police department in the United States, 2,000 private spy cameras owned by Wall Street firms, together with approximately 1,000 more owned by the NYPD, are relaying live video feeds of people on the streets in lower Manhattan to the center. Once at the center, they can be integrated for analysis. At least 700 cameras scour the midtown area and also relay their live feeds into the downtown center where low-wage NYPD, MTA and Port Authority crime stoppers sit alongside high-wage personnel from Wall Street firms that are currently under at least 51 Federal and state corruption probes for mortgage securitization fraud and other matters.

In addition to video analytics which can, for example, track a person based on the color of their hat or jacket, insiders say the NYPD either has or is working on face recognition software which could track individuals based on facial features. The center is also equipped with live feeds from license plate readers.

Michael Moore and Cornel West on Occupy Wall Street

Why Occupy Wall Street wants nothing to do with our politicians

Heather Gautney asks: Is this what democracy looks like? That’s perhaps the first question prompted by the swirl of tents, signs, news choppers and police motorcycles that have colored the Occupy Wall Street protests. But there are two other questions we should be asking as well. Is democracy even possible in a context of extreme instability and social inequality, in which 1 percent of the population owns and polices the other 99 percent? And who, among our distinguished set of 2012 candidates, really wants to narrow this gap?

Thus far, the Occupy movement is checking “None of the Above” on the ballot box. Since mid-September, it has instead decided to represent itself in the streets. And if you think there aren’t concrete, policy-related demands being made there, have another look: Everything from education to housing, health care, environment, energy and security are up for grabs. All of these institutions are in need of fixing, and all of them are making the list.

These acts of self-representation—or direct democracy—do not compute among mainstream politicians and their pundits. Occupy does not speak the language of party or ideology, and this has not boded well for a system that relies on polls, predictability and reductive thought. Social movements are, by their very nature, complex, organic and indeterminate. They operate at the deepest levels of how we view each other and the world we live in.

This movement is no exception. You can’t reduce this kind of public outcry to dichotomies like liberal and conservative, or Blue and Red. And you certainly can’t dismiss it as fringe and un-American. Occupy is a popular movement, not a Tea Party, and the act of sticking up for yourself is as American as apple pie.

Despite this apparent disconnect, the Occupy movement has received honorable mention at the highest levels of government, though I suspect this has more to do with polls and constituencies than with genuine understanding. After a Time Magazine survey revealed that 54 percent of Americans actually support these rabble-rousers, our politicians started to take notice. Occupy is actually more popular among the American people than the U.S. Congress—and that must really hurt.

That 54-percent figure was likely behind flip-flopper Mitt Romney’s overnight change of heart. Just days into October, Romney called the protesters “dangerous” instigators of “class warfare.” A week later, he switched gears and expressed “worry” for the 99 percenters. All the sudden this multi-millionaire, private-sector guru has become a man of the people. Who knew?

Then there’s Barack Obama. The guy we all wanted to love. With his usual charm, he empathized with the Occupy-ers, said not everyone in Corporate America was playing by the rules and, once again, took us on a stroll down Main Street. But in the tug of war between Main Street and Wall Street, Obama has made his loyalties clear. Just take a look at the long list of Wall Street contributors to his campaign. Unfortunately, Mr. President, you are the company you keep.

Occupy newsrooms

David Carr on the parasitic behavior of newspaper executives: Almost two weeks ago, USA Today put its finger on why the Occupy Wall Street protests continued to gain traction.

“The bonus system has gone beyond a means of rewarding talent and is now Wall Street’s primary business,” the newspaper editorial stated, adding: “Institutions take huge gambles because the short-term returns are a rationale for their rich payouts. But even when the consequences of their risky behavior come back to haunt them, they still pay huge bonuses.”

Well thought and well put, but for one thing: If you were looking for bonus excess despite miserable operations, the best recent example I can think of is Gannett, which owns USA Today.

The week before the editorial ran, Craig A. Dubow resigned as Gannett’s chief executive. His short six-year tenure was, by most accounts, a disaster. Gannett’s stock price declined to about $10 a share from a high of $75 the day after he took over; the number of employees at Gannett plummeted to 32,000 from about 52,000, resulting in a remarkable diminution in journalistic boots on the ground at the 82 newspapers the company owns.

Never a standout in journalism performance, the company strip-mined its newspapers in search of earnings, leaving many communities with far less original, serious reporting.

Given that legacy, it was about time Mr. Dubow was shown the door, right? Not in the current world we live in. Not only did Mr. Dubow retire under his own power because of health reasons, he got a mash note from Marjorie Magner, a member of Gannett’s board, who said without irony that “Craig championed our consumers and their ever-changing needs for news and information.”

But the board gave him far more than undeserved plaudits. Mr. Dubow walked out the door with just under $37.1 million in retirement, health and disability benefits. That comes on top of a combined $16 million in salary and bonuses in the last two years.

And in case you thought they were paying up just to get rid of a certain way of doing business — slicing and dicing their way to quarterly profits — Mr. Dubow was replaced by Gracia C. Martore, the company’s president and chief operating officer. She was Mr. Dubow’s steady accomplice in working the cost side of the business, without finding much in the way of new revenue. She has already pocketed millions in bonuses and will now be in line for even more.

Forget about occupying Wall Street; maybe it’s time to start occupying Main Street, a place Gannett has bled dry by offering less and less news while dumping and furloughing journalists in seemingly every quarter.

Occupy everywhere: protesters in their own words

From Frankfurt to Madrid, Wall Street to Athens, people are taking to the streets to rage against greed and inequality. The Guardian records some of their messages:

The bankers that rule the world

New Scientist reports: As protests against financial power sweep the world this week, science may have confirmed the protesters’ worst fears. An analysis [PDF] of the relationships between 43,000 transnational corporations has identified a relatively small group of companies, mainly banks, with disproportionate power over the global economy.

The study’s assumptions have attracted some criticism, but complex systems analysts contacted by New Scientist say it is a unique effort to untangle control in the global economy. Pushing the analysis further, they say, could help to identify ways of making global capitalism more stable.

The idea that a few bankers control a large chunk of the global economy might not seem like news to New York’s Occupy Wall Street movement and protesters elsewhere. But the study, by a trio of complex systems theorists at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, is the first to go beyond ideology to empirically identify such a network of power. It combines the mathematics long used to model natural systems with comprehensive corporate data to map ownership among the world’s transnational corporations (TNCs).

“Reality is so complex, we must move away from dogma, whether it’s conspiracy theories or free-market,” says James Glattfelder. “Our analysis is reality-based.”

Previous studies have found that a few TNCs own large chunks of the world’s economy, but they included only a limited number of companies and omitted indirect ownerships, so could not say how this affected the global economy – whether it made it more or less stable, for instance.

The Zurich team can. From Orbis 2007, a database listing 37 million companies and investors worldwide, they pulled out all 43,060 TNCs and the share ownerships linking them. Then they constructed a model of which companies controlled others through shareholding networks, coupled with each company’s operating revenues, to map the structure of economic power.

The work, to be published in PloS One, revealed a core of 1318 companies with interlocking ownerships (see image). Each of the 1318 had ties to two or more other companies, and on average they were connected to 20. What’s more, although they represented 20 per cent of global operating revenues, the 1318 appeared to collectively own through their shares the majority of the world’s large blue chip and manufacturing firms – the “real” economy – representing a further 60 per cent of global revenues.

When the team further untangled the web of ownership, it found much of it tracked back to a “super-entity” of 147 even more tightly knit companies – all of their ownership was held by other members of the super-entity – that controlled 40 per cent of the total wealth in the network. “In effect, less than 1 per cent of the companies were able to control 40 per cent of the entire network,” says Glattfelder. Most were financial institutions. The top 20 included Barclays Bank, JPMorgan Chase & Co, and The Goldman Sachs Group.

John Driffill of the University of London, a macroeconomics expert, says the value of the analysis is not just to see if a small number of people controls the global economy, but rather its insights into economic stability.

Concentration of power is not good or bad in itself, says the Zurich team, but the core’s tight interconnections could be. As the world learned in 2008, such networks are unstable. “If one [company] suffers distress,” says Glattfelder, “this propagates.”

“It’s disconcerting to see how connected things really are,” agrees George Sugihara of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, California, a complex systems expert who has advised Deutsche Bank.

The top 25 of the 147 superconnected companies

1. Barclays plc

2. Capital Group Companies Inc

3. FMR Corporation

4. AXA

5. State Street Corporation

6. JP Morgan Chase & Co

7. Legal & General Group plc

8. Vanguard Group Inc

9. UBS AG

10. Merrill Lynch & Co Inc

11. Wellington Management Co LLP

12. Deutsche Bank AG

13. Franklin Resources Inc

14. Credit Suisse Group

15. Walton Enterprises LLC

16. Bank of New York Mellon Corp

17. Natixis

18. Goldman Sachs Group Inc

19. T Rowe Price Group Inc

20. Legg Mason Inc

21. Morgan Stanley

22. Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group Inc

23. Northern Trust Corporation

24. Société Générale

25. Bank of America Corporation

Listening Post – From Occupy Wall Street to Occupy Everywhere

How to make banks really mad: occupy foreclosures

Mike Konczal asks: Could the next step after camping in Zuccotti Park be camping out in homes facing foreclosure?

As people think a bit more critically about what it means to “occupy” contested spaces that blur the public and the private and the boundaries between the 99% and the 1%, and as they also think through what Occupy Wall Street might do next, I would humbly suggest they check out the activism model of Project: No One Leaves. It exists in many places, especially in Massachusetts — check out this Springfield version of it — and grows out of activism pioneered by City Life Vida Urbana. It is similar to activism done by the group New Bottom Line and other foreclosure fighters. Here is PBS NewsHour’s coverage of the movement.

Former financial regulator William Black: Occupy Wall Street a counter to white-collar fraud

How the austerity class rules Washington

Ari Berman writes: In September the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (CRFB), a bipartisan deficit-hawk group based at the New America Foundation, held a high-profile symposium urging the Congressional “supercommittee” to “go big” and approve a $4 trillion deficit reduction plan over the next decade, which is well beyond its $1.2 trillion mandate. The hearing began with an alarming video of top policy-makers describing the national debt as “the most serious threat that this country has ever had” (Alan Simpson) and “a threat to the whole idea of self-government” (Mitch Daniels). If the debt continues to rise, predicted former New Mexico Senator Pete Domenici, there would be “strikes, riots, who knows what?” A looming fiscal crisis was portrayed as being just around the corner.

The event spotlighted a central paradox in American politics over the past two years: how, in the midst of a massive unemployment crisis—when it’s painfully obvious that not enough jobs are being created and the public overwhelmingly wants policy-makers to focus on creating them—did the deficit emerge as the most pressing issue in the country? And why, when the global evidence clearly indicates that austerity measures will raise unemployment and hinder, not accelerate, growth, do advocates of austerity retain such distinction today?

An explanation can be found in the prominence of an influential and aggressive austerity class—an allegedly centrist coalition of politicians, wonks and pundits who are considered indisputably wise custodians of US economic policy. These “very serious people,” as New York Times columnist Paul Krugman wryly dubs them, have achieved what University of California, Berkeley, economist Brad DeLong calls “intellectual hegemony over the course of the debate in Washington, from 2009 until today.”

Its members include Wall Street titans like Pete Peterson and Robert Rubin; deficit-hawk groups like the CRFB, the Concord Coalition, the Hamilton Project, the Committee for Economic Development, Third Way and the Bipartisan Policy Center; budget wonks like Peter Orszag, Alice Rivlin, David Walker and Douglas Holtz-Eakin; red state Democrats in Congress like Mark Warner and Kent Conrad, the bipartisan “Gang of Six” and what’s left of the Blue Dog Coalition; influential pundits like Tom Friedman and David Brooks of the New York Times, Niall Ferguson and the Washington Post editorial page; and a parade of blue ribbon commissions, most notably Bowles-Simpson, whose members formed the all-star team of the austerity class.

The austerity class testifies frequently before Congress, is quoted constantly in the media by sympathetic journalists and influences policy-makers and elites at the highest levels of power. They manufacture a center-right consensus by determining the parameters of acceptable debate and policy priorities, deciding who is and is not considered a respectable voice on fiscal matters. The “balanced” solutions they advocate are often wildly out of step with public opinion and reputable economic policy, yet their influence endures, thanks to an abundance of money, the ear of the media, the anti-Keynesian bias of supply-side economics and a political system consistently skewed to favor Wall Street over Main Street.

99ers join Occupy Wall Street movement

Arthur Delaney writes: Fed up with a long jobless spell, Kian Frederick raged against economic injustice during a protest in New York City.

“We’re tired of blaming the victim,” Frederick said during a speech before she and three others were arrested for blocking the street. “If you’re not in the richest 2 percent, you’re struggling. We have to ask the question, why are corporations, major corporations, sitting on millions and billions of record profits by their own account yet they’re still not hiring? We have to ask the question why our government continues to fight itself and ignore our needs.”

Her speech and arrest happened last November, nearly a year before the Occupy Wall Street protests became an international sensation. Way before many of the occupiers took up the cause of the 99 percent, there were “99ers” — the very long-term jobless. Their protests were smaller, and they got less attention. Now several 99ers and the long-term jobless, including Frederick, have joined the Occupy Wall Street cause.

How income inequality skyrocketed and the 1 percent profited from the decline of unions

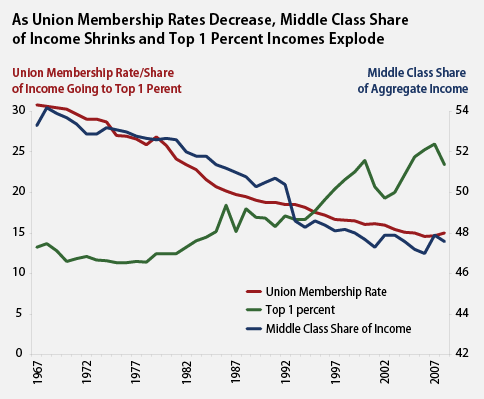

Zaid Jilani writes: This evening, House Majority Leader Eric Cantor (R-VA) will give a speech at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business about how to address income inequality, likely trying to capitalize on the 99 Percent Movement he once derided as unruly “mobs.” Although exactly what policies Cantor will suggest to deal with this social problem are unknown, it’s unlikely that he will touch on one of the chief drivers of American income inequality: the decline of unions.

As CAP’s David Madland and Nick Bunker show in the following chart, the middle class’s share of national income has steadily declined as the percentage of the population in labor unions has fallen. At the same time, the top 1 percent’s share of national income has exploded:

Nassim Taleb’s perspective on Occupy Wall Street

Obama’s gift to the Koch brothers and curse to the planet

Jamie Henn, Co-founder and Communications Director of 350.org, writes: Here’s a unique political strategy for you: in the lead up to a crucial election, as anti-corporate sentiment is sweeping the nation, consider giving a huge handout to a major corporation that happens to be your biggest political enemy and is already spending hundreds of millions to defeat you and your agenda.

If that seems too crazy to believe, welcome to the Obama 2012 campaign.

Right now, President Obama is faced with the most crucial environmental decisions he is going to face before the 2012 election: whether or not to approve the permit for the controversial Keystone XL pipeline, a 1,700 mile fuse to the largest carbon bomb on the continent, the Canadian tar sands.

The Keystone XL isn’t just an XL environmental disaster — the nation’s top climate scientists say that fully exploiting the tar sands could mean “essentially game over” for the climate — it also happens to be an XL sized handout to Big Oil and, you guessed it, the Brothers Koch. You want fries with that?

Earlier this year, when Representative Henry Waxman (D-Calif.) attempted to investigate whether or not the Koch Brothers stood to gain from the pipeline, the chairman of the House Committee on Energy and Commerce, Fred Upton (R-Mich.) called the idea an “outrageous accusation” and “blatant political sideshow.” Is it even necessary to mention that reports show Koch and its employees gave $279,500 to 22 of the energy committee’s 31 Republicans and $32,000 to five Democrats?

As you might expect, Upton was completely wrong. Reporters at InsideClimateNews and elsewhere proved that the Koch’s stand to make a fortune with the construction of the pipeline. The brothers already control close to 25 percent of the tar sands crude that is imported into the United State and own mining companies, oil terminals, and refineries all along the pipeline route. You can bet that the champagne will be flowing in Koch HQ when toxic tar sands crude starts moving down the pipe.

Which brings us back to Obama. It’s not too late for the president to intervene and stop the Koch Brothers from pocketing another profit at the expense of the American people. Because it crosses an international border, in order for the Keystone XL pipeline to be built the Obama administration must grant it a “presidential permit” that states that the construction project is in the national interest of the United States.

President Obama can deny the permit, right now, and shut down this flow of cash to the Kochs. In doing so, he’ll show that our national interest isn’t always determined by the 1%, in this case a few big oil companies and the Koch Brothers, but by the 99% of us who have to pay the price for their greed.

Denying the permit will also send a jolt of electricity through President Obama’s base, the millions of us who went out and volunteered and donated to the campaign because we believed in a candidate who said that it was time to “end the tyranny of oil.” In fact, this November 6, thousands of us former believers will be descending on Washington, DC to surround the White House with people carrying placards with the President’s own words in an attempt to resuscitate the 2008 Obama who seemed capable of standing up to folks like the Kochs. You can join here.

I can’t say that I’m privy to what the Obama 2012 campaign will advise the president to do when it comes to the pipeline. But if I was sitting in Chicago watching the Koch Brothers assembled their army of lobbyists across the nation, I’d be thinking that XL handout wasn’t such a good idea.

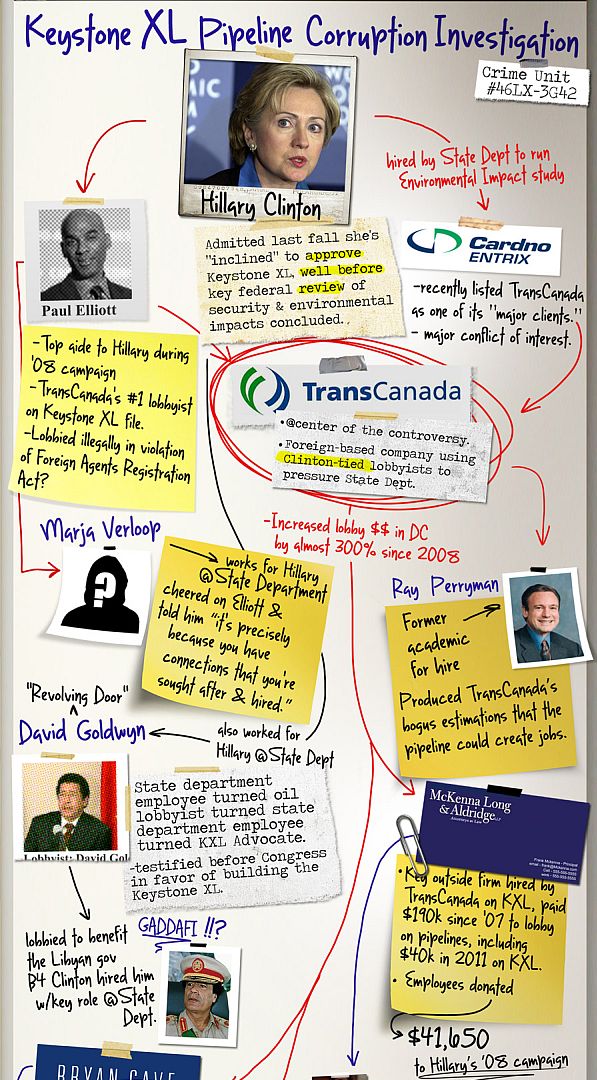

The Keystone XL pipeline network of corruption revealed through an investigation by DeSmogBlog, Oil Change International, The Other 98% and Friends of the Earth (click on the image below to view the complete network):