Chris McGreal reports from Ras Lanuf, where thousands of young volunteers now provide the bulk of the rebel force that has swept along Libya’s eastern coast:

Gaddafi’s air force has bombed Ras Lanuf repeatedly, cutting off the town’s water supply on Tuesday and destroying housing. On Monday the victims included a civilian, Mohammed Ashtal, who was killed with three of his children when an air strike hit their car.

The bombing has put the inexperienced fighters on edge as they constantly scan the sky for planes. Every now and then a shout goes up. Someone claims there is a MiG jet. No one can see it but hundreds of weapons let loose in a futile wave of fire in every direction. Young men swivel anti-aircraft guns, letting go bursts of shells with a deadening thud. Kalashnikov bullets pop furiously.

Not long after one such false alarm, the young fighters raced out of town towards the front despite the pleas of their more experienced commanders to maintain their defensive lines and positions guarding a nearby oil refinery.

It was all very worrying for Fathi Mohammed, torn between admiration of young men willing to risk their lives in pursuit of freedom and despair at their lack of discipline. The 46-year-old former captain in Gaddafi’s special forces is trying to instil some organisation in the bands of fighters who have descended on Ras Lanuf.

“They’re not under control,” he said. “Some of these guys, they just took guns from the military camp in Benghazi and came here without anyone knowing what they are doing. We are trying to make them into organised teams but it’s not easy.”

Rajab Hasan, another former soldier tasked with training, chipped in: “They need a leader. We don’t have enough leaders.”

Mohammed expressed his concern at the implications of all this carefully. The rebel army has done well until now, advancing and then staving off attempts by Gaddafi’s forces to break through. But he acknowledged that the rebels could face a problem if its enemy is able to launch a sustained attack.

Mohammed does not want to concede that defeat might be a possibility, even though a rumour has swept the rebels that Gaddafi is amassing tanks for a frontal assault. But he does recognise that victory is not certain. “It’s not impossible to get to Tripoli. If God is with us,” he said. Still, Mohammed does not question the courage of the young fighters. “They are brave. They have the courage. It’s a popular war. There’s a lot of enthusiasm.”

The New York Times reports:

In less than three weeks, an inchoate opposition in Libya, one of the world’s most isolated countries, has cobbled together the semblance of a transitional government, fielded a ragtag rebel army and portrayed itself to the West and Libyans as an alternative to Col. Muammar el-Qaddafi’s four decades of freakish rule.

But events this week have tested the viability of an opposition that has yet to coalesce, even as it solicits help from abroad to topple Colonel Qaddafi’s government.

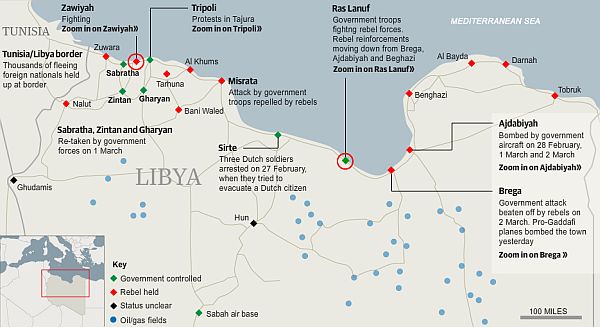

Rebels were dealt military setbacks in Zawiyah and the on outskirts of Ras Lanuf on Tuesday, part of a strengthening government counteroffensive. Meanwhile, the oppostion council’s leaders contradicted one another publicly. The opposition’s calls for foreign aid have amplified divisions over intervention. And provisional leaders warn that a humanitarian crisis may loom as people’s needs overwhelm fledgling local governments.

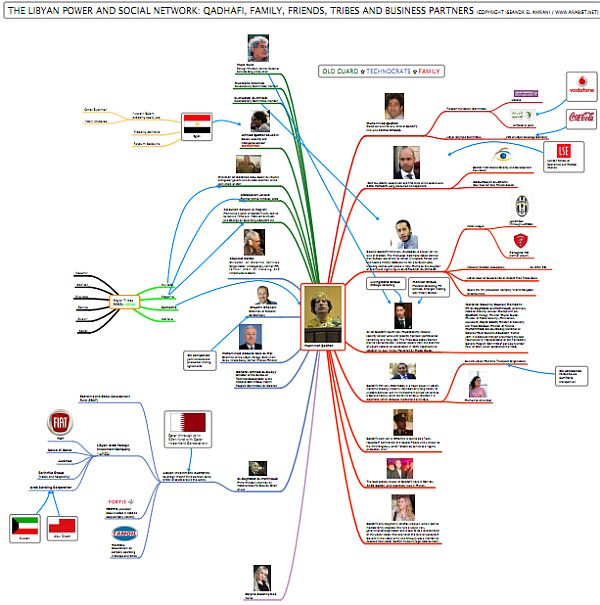

“I am Libya,” Colonel Qaddafi boasted after the uprising erupted. It was standard fare for one of the world’s most outrageous leaders — megalomania so pronounced that it sounded like parody. It underlined, though, the greatest and perhaps fatal obstacle facing the rebels here — forging a substitute to Colonel Qaddafi in a state that he embodied.

“We’ve found ourselves in a vacuum,” Mustafa Gheriani, an acting spokesman for the provisional leadership, said Tuesday in Benghazi, the rebel capital. “Instead of worrying about establishing a transitional government, all we worry about are the needs — security, what people require, where the uprising is going. Things are moving too fast.”

“This is all that’s left,” he said, lifting his cellphone, “and we can only receive calls.”

The question of the opposition’s capabilities is likely to prove decisive to the fate of the rebellion, which appears outmatched by government forces and troubled by tribal divisions that the government, reverting to form, has sought to exploit. Rebel forces are fired more by enthusiasm than experience. The political leadership has virtually begged the international community to recognize it, but it has yet to marshal opposition forces abroad or impose its authority in regions it nominally controls.

The Guardian reports:

Nato has launched 24-hour air and sea surveillance of Libya as a possible precursor to a no-fly zone, amid signs of growing Arab support for western military intervention to stop the bombing of civilians.

British and French diplomats at the UN headquarters in New York have completed a draft resolution authorising the creation of a no-fly zone which could be put before the security council within hours if aerial bombing by pro-Gaddafi forces causes mass civilian casualties.

“It would require a clear trigger for a resolution to go forward,” a western diplomat said. In such an event, there would be pressure on Russia and China not to use vetoes. Western officials believe support for a no-fly zone from the Islamic world, as well as from the Libyan opposition and Libyan diplomats at the UN, would put Moscow and Beijing on the defensive.

The Gulf Co-operation Council, the Organisation of the Islamic Conference and the secretary general of the Arab League have called for the protection of Libyan civilians while rejecting the intervention of western ground troops. Turkey, the most reluctant Nato member state, has relaxed its opposition and allowed contingency planning to go ahead.

The decision to step up air and sea monitoring was taken on Monday by the North Atlantic Council, a meeting of ambassadors from Nato’s 28 member states.

Foreign Policy reports:

The State Department believes that supplying any arms to the Libyan opposition to support their struggle against Col. Muammar al-Qaddafi would be illegal at the current time.

“It’s very simple. In the U.N. Security Council resolution passed on Libya, there is an arms embargo that affects Libya, which means it’s a violation for any country to provide arms to anyone in Libya,” State Department spokesman P.J. Crowley said on Monday.

Crowley denied reports that the United States had asked Saudi Arabia to provide weapons to the Libyan opposition, and also denied that the United States would arm opposition groups absent explicit international authorization.

Pressed by reporters to clarify whether the Obama administration had any plans to give arms to any of the rebel groups in Libya, Crowley said no.

“It would be illegal for the United States to do that,” he said. “It’s not a legal option.”

Crowley’s blanket statement seemed to go further than comments on Monday by White House spokesman Jay Carney, who said, “On the issue of … arming, providing weapons, it is one of the range of options that is being considered.”

The New York Times reports:

As wealthier nations send boats and planes to rescue their citizens from the violence in Libya, a new refugee crisis is taking shape on the outskirts of Tripoli, where thousands of migrant workers from sub-Saharan Africa have been trapped with scant food and water, no international aid and little hope of escape.

The migrants — many of them illegal immigrants from Ghana and Nigeria who have long constituted an impoverished underclass in Libya — live amid piles of garbage, sleep in makeshift tents of blankets strung from fences and trees, and breathe fumes from a trench of excrement dividing their camp from the parking lot of Tripoli’s airport.

For dinner on Monday night two men killed a scrawny, half-plucked chicken by dunking it in water boiled on a garbage fire, then hacked it apart with a dull knife and cooked it over an open fire. Some residents of the camp are as young as Essem Ighalo, 9 days old, who arrived on his second day of life and has yet to see a doctor. Many refugees said they had seen deaths from hunger and disease every night.

The airport refugees, along with tens of thousands of other African migrants lucky enough to make it across the border to Tunisia, are the most desperate contingent of a vast exodus that has already sent almost 200,000 foreigners fleeing the country since the outbreak of the popular revolt against Col. Muammar el-Qaddafi nearly three weeks ago.

Libya’s Interim Transitional National Council now has a website with this introductory statement:

In this important historical juncture which Libya is passing through right now, we find ourselves at a turning point with only two solutions. Either we achieve freedom and race to catch up with humanity and world developments, or we are shackled and enslaved under the feet of the tyrant Mu’ammar Gaddafi where we shall live in the midst of history. From this junction came the announcement of the Transitional National Council, a step on the road to liberate every part of the Libyan lands from Aamsaad in the east to Raas Ajdair in the west, and from Sirte in the north to Gatrun in the south. To liberate Libya from the hands of the tyrant Mu’ammar Gaddafi who made lawful to himself the exploitation of his people and the wealth of this country. The number of martyrs and wounded and the extreme use of excessive force and mercenaries against his own people requires us to take the initiative and work on the Liberalization of Libya from such insanities.

To reach this goal, the Transitional National Council announced its official establishment on 5th March 2011 in the city of Benghazi, stating its perseverance towards the aim of relocating its headquarters to our capital and bride of the Mediterranean, the city of Tripoli.

To connect with our people at home and abroad, and to deliver our voice to the outside world, we have decided to establish this website as the official window of communication via the world wide web.

May peace and God’s mercy and blessings be upon you

Long live Libya free and dignified

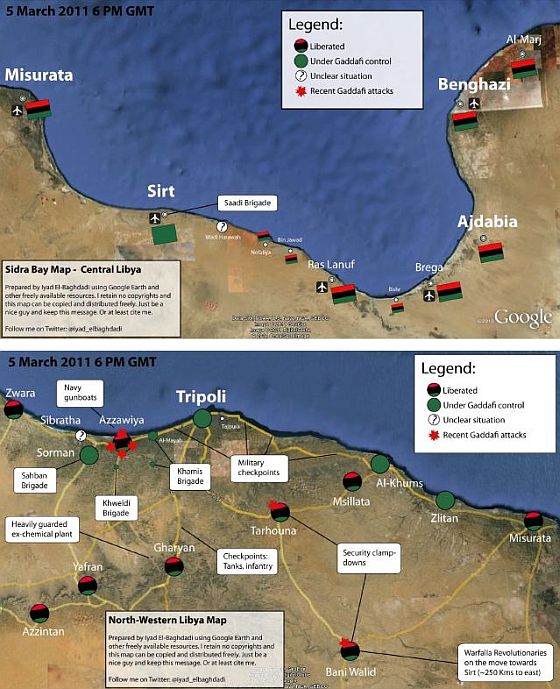

Map of the revolution: